Boolean circuit

In computational complexity theory and circuit complexity, a Boolean circuit is a mathematical model for combinational digital logic circuits. A formal language can be decided by a family of Boolean circuits, one circuit for each possible input length. Boolean circuits are also used as a formal model for combinational logic in digital electronics.

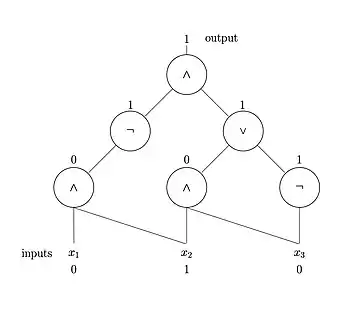

Boolean circuits are defined in terms of the logic gates they contain. For example, a circuit might contain binary AND and OR gates and unary NOT gates, or be entirely described by binary NAND gates. Each gate corresponds to some Boolean function that takes a fixed number of bits as input and outputs a single bit.

Boolean circuits provide a model for many digital components used in computer engineering, including multiplexers, adders, and arithmetic logic units, but they exclude sequential logic. They are an abstraction that omits many aspects relevant to designing real digital logic circuits, such as metastability, fanout, glitches, power consumption, and propagation delay variability.

Formal definition

In giving a formal definition of Boolean circuits, Vollmer starts by defining a basis as set B of Boolean functions, corresponding to the gates allowable in the circuit model. A Boolean circuit over a basis B, with n inputs and m outputs, is then defined as a finite directed acyclic graph. Each vertex corresponds to either a basis function or one of the inputs, and there is a set of exactly m nodes which are labeled as the outputs.[1] The edges must also have some ordering, to distinguish between different arguments to the same Boolean function.[2]

As a special case, a propositional formula or Boolean expression is a Boolean circuit with a single output node in which every other node has fan-out of 1. Thus, a Boolean circuit can be regarded as a generalization that allows shared subformulas and multiple outputs.

A common basis for Boolean circuits is the set {AND, OR, NOT}, which is functionally complete, i. e. from which all other Boolean functions can be constructed.

Computational complexity

Background

A particular circuit acts only on inputs of fixed size. However, formal languages (the string-based representations of decision problems) contain strings of different lengths, so languages cannot be fully captured by a single circuit (in contrast to the Turing machine model, in which a language is fully described by a single Turing machine). A language is instead represented by a circuit family. A circuit family is an infinite list of circuits , where has input variables. A circuit family is said to decide a language if, for every string , is in the language if and only if , where is the length of . In other words, a language is the set of strings which, when applied to the circuits corresponding to their lengths, evaluate to 1.[3]

Complexity measures

Several important complexity measures can be defined on Boolean circuits, including circuit depth, circuit size, and number of alternations between AND gates and OR gates. For example, the size complexity of a Boolean circuit is the number of gates.

It turns out that there is a natural connection between circuit size complexity and time complexity.[4] Intuitively, a language with small time complexity (that is, requires relatively few sequential operations on a Turing machine), also has a small circuit complexity (that is, requires relatively few Boolean operations). Formally, it can be shown that if a language is in , where is a function , then it has circuit complexity .

Complexity classes

Several important complexity classes are defined in terms of Boolean circuits. The most general of these is P/poly, the set of languages that are decidable by polynomial-size circuit families. It follows directly from the fact that languages in have circuit complexity that PP/poly. In other words, any problem that can be computed in polynomial time by a deterministic Turing machine can also be computed by a polynomial-size circuit family. It is further the case that the inclusion is proper (i.e. PP/poly) because there are undecidable problems that are in P/poly. P/poly turns out to have a number of properties that make it highly useful in the study of the relationships between complexity classes. In particular, it is helpful in investigating problems related to P versus NP. For example, if there is any language in NP that is not in P/poly then PNP.[5] P/poly also helps to investigate properties of the polynomial hierarchy. For example, if NP ⊆ P/poly, then PH collapses to . A full description of the relations between P/poly and other complexity classes is available at "Importance of P/poly". P/poly also has the interesting feature that it can be equivalently defined as the class of languages recognized by a polynomial-time Turing machine with a polynomial-bounded advice function.

Two subclasses of P/poly that have interesting properties in their own right are NC and AC. These classes are defined not only in terms of their circuit size but also in terms of their depth. The depth of a circuit is the length of the longest directed path from an input node to the output node. The class NC is the set of languages that can be solved by circuit families that are restricted not only to having polynomial-size but also to having polylogarithmic depth. The class AC is defined similarly to NC, however gates are allowed to have unbounded fan-in (that is, the AND and OR gates can be applied to more than two bits). NC is an important class because it turns out that it represents the class of languages that have efficient parallel algorithms.

Circuit evaluation

The Circuit Value Problem — the problem of computing the output of a given Boolean circuit on a given input string — is a P-complete decision problem.[6] Therefore, this problem is considered to be "inherently sequential" in the sense that there is likely no efficient, highly parallel algorithm that solves the problem.

Footnotes

- Vollmer 1999, p. 8.

- Vollmer 1999, p. 9.

- Sipser, Michael (2006). Introduction to the Theory of Computation (2nd ed.). USA: Thomson Course Technology. p. 354. ISBN 978-0-534-95097-2.

- Sipser, Michael (2006). Introduction to the Theory of Computation (2nd ed.). USA: Thomson Course Technology. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-534-95097-2.

- Arora, Sanjeev; Barak, Boaz (2009). Computational Complexity: A Modern Approach. Cambridge University Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-521-42426-4.

- Arora, Sanjeev; Barak, Boaz (2009). Computational Complexity: A Modern Approach. Cambridge University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-521-42426-4.

References

- Vollmer, Heribert (1999). Introduction to Circuit Complexity. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-64310-9.