Ciudad Juárez

Ciudad Juárez (/ˈhwɑːrɛz/ HWAH-rez; Juarez City. Spanish pronunciation: [sjuˈðað ˈxwaɾes] (![]() listen)) is the most populous city in the Mexican state of Chihuahua.[3] The city is commonly referred to as simply Juárez, and was known as El Paso del Norte (The Pass of the North) until 1888.[4] Juárez is the seat of the Juárez Municipality with an estimated population of 1.5 million people.[5] It lies on the Rio Grande (Río Bravo del Norte) river, south of El Paso, Texas, United States. Together with the surrounding areas, the cities form El Paso–Juárez, the second largest binational metropolitan area on the Mexico–U.S. border (after San Diego–Tijuana), with a combined population of over 2.7 million people.[6]

listen)) is the most populous city in the Mexican state of Chihuahua.[3] The city is commonly referred to as simply Juárez, and was known as El Paso del Norte (The Pass of the North) until 1888.[4] Juárez is the seat of the Juárez Municipality with an estimated population of 1.5 million people.[5] It lies on the Rio Grande (Río Bravo del Norte) river, south of El Paso, Texas, United States. Together with the surrounding areas, the cities form El Paso–Juárez, the second largest binational metropolitan area on the Mexico–U.S. border (after San Diego–Tijuana), with a combined population of over 2.7 million people.[6]

Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua | |

|---|---|

Collage of Juárez scenes | |

Coat of arms | |

| Nicknames: El Paso del Norte, "Juárez" | |

| Motto(s): Refugio de la libertad, custodia de la república (Spanish for "Refuge of liberty, guard of the republic") | |

Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua  Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua | |

| Coordinates: 31°44′18.89″N 106°29′13.25″W | |

| Country | |

| State | Chihuahua |

| Municipality | Juárez |

| Foundation | 1659 |

| Government | |

| • Municipal president | Héctor Armando Cabada Alvídrez (Ind.) |

| Area | |

| • City | 321.19 km2 (124.01 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,137 m (3,730 ft) |

| Population (2010)[1] | |

| • City | 1,321,004 |

| • Density | 7,027/km2 (10,653.26/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,539,946[2] |

| • Demonym | Juarense |

| Time zone | UTC−07:00 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−06:00 (MDT) |

| Area code(s) | +52 656 |

| Climate | BWk |

| Website | http://www.juarez.gob.mx |

Four international points of entry connect Ciudad Juárez and El Paso: the Bridge of the Americas, the Ysleta International Bridge, the Paso del Norte Bridge, and the Stanton Street Bridge. Combined, these bridges allowed 22,958,472 crossings in 2008,[7] making Ciudad Juárez a major point of entry and transportation into the U.S. for all of central northern Mexico. The city has a growing industrial center, which in large part is made up by more than 300 "maquiladoras" (assembly plants) located in and around the city. According to a 2007 New York Times article, Ciudad Juárez was "absorbing more new industrial real estate space than any other North American city".[5] In 2008, fDi Magazine designated Ciudad Juárez "The City of the Future".[8]

History

As 17th century Spanish explorers sought a route through the southern Rocky Mountains, the Franciscan Friar García de San Francisco founded Ciudad Juárez in 1659 as "El Paso del Norte" ("The North Pass"). The Misión de Guadalupe de los Mansos en el Paso del río del Norte became the first permanent Spanish development in the area in the 1660s, although Native American peoples were already present. The Franciscan friars established a community that grew in importance as commerce between Santa Fe and Chihuahua passed through it. The wood for the first bridge across the Rio Grande came from Santa Fe, New Mexico in the late 18th century. The original population of Mansos, Suma, Jumano, and other natives from the south brought by the Spanish from Central New Spain grew around the mission. In 1680 during the Pueblo Revolt, most of the Piro Pueblo and some of the Tiwa people branch of the Pueblo became refugees, A Mission was established for the Tigua in Ysleta del Sur. Piro Pueblo colonial era settlements along El Camino Real, south of the Guadalupe Mission, included Missions Real de San Lorenzo, Senecú del Sur, and Soccoro del Sur. Presidio del Nuestra Senora del Pilar del Paso del Rio Norte was established near the Mission in 1683.[9]:39–96

The population of the entire district was close to 5,000 in 1750 when the Apache attacked the other native towns and ranchos around the missions. Additional Presidios were established to counter them. One Presidio, San Elzeario, was established near El Porvenir in 1774, where it remained until being moved in 1788 to what is now San Elizario, Texas where that settlement grew up around that Presidio. Another was Presidio de San Fernando de Carrizal, which was established in 1774 at the San Fernando settlement that became present-day Carrizal, Chihuahua.[9]:39–40

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo established the Rio Grande as the border between Mexico and the United States. The main channel of the Rio Grande had moved southwestward leaving the settlements of Ysleta, Socorro, and San Elzeario on the Camino Real on the north bank of the river, isolated from the rest of the towns, in Texas.

Other settlements on the east bank of the Rio Grande were not part of a town at that time; as the U.S. Army set up its installations settlements grew around it. This would later become El Paso, Texas. From that time until around 1930, populations on both sides of the border moved freely across it.

During the French intervention in Mexico (1862–1867), Benito Juárez's republican forces stopped temporarily at El Paso del Norte before establishing his government-in-exile in Chihuahua. After 1882, the city grew, in large part, because of the arrival of the Mexican Central Railway. Commerce thrived in the city as more banks began operating, telegraph and telephone services became available, and trams appeared. These commercial activities were under the firm control of the city's oligarchy, which consisted of the Ochoa, Samaniego, Daguerre, Provencio, and Cuarón families. In 1888, El Paso del Norte was renamed in honor of Benito Juárez.

The city expanded significantly thanks to Díaz's free-trade policy, creating a new retail and service sector along the old Calle del Comercio (now Vicente Guerrero) and September 16 Avenue. A bullring opened in 1899. The Escobar brothers founded the city's first institution of higher education in 1906, the Escuela Particular de Agricultura. That same year, a series of public works are inaugurated, including the city's sewage and drainage system, as well as potable water. A public library, schools, new public market (the old Mercado Cuauhtémoc) and parks dotted the city, making it one of many Porfirian showcases. Modern hotels and restaurants catered to the increased international railroad traffic from the 1880s on.

In 1909, Díaz and William Howard Taft planned a summit in Ciudad Juárez and El Paso, a historic first meeting between a Mexican and a U.S. president, and also the first time a U.S. president would cross the border into Mexico.[10] But tensions rose on both sides of the border over the disputed Chamizal strip connecting Ciudad Juárez to El Paso, even though it would have been considered neutral territory with no flags present during the summit.[11] The Texas Rangers, 4,000 U.S. and Mexican troops, U.S. Secret Service agents, FBI agents and U.S. marshals were all called in to provide security.[12] Frederick Russell Burnham, the celebrated scout, was put in charge of a 250 private security detail hired by John Hays Hammond.[13][14] On October 16, the day of the summit, Burnham and Private C.R. Moore, a Texas Ranger, discovered a man holding a concealed palm pistol standing at the El Paso Chamber of Commerce building along the procession route.[15][16] Burnham and Moore captured, disarmed, and arrested the assassin within only a few feet of Díaz and Taft.[17][18]

The city was Mexico's largest border town by 1910—and as such, it held strategic importance during the Mexican Revolution. In May 1911, about 3,000 revolutionary fighters under the leadership of Francisco Madero laid siege to Ciudad Juárez, which was garrisoned by 500 regular Federal troops under the command of General Juan J Navarro. Navarro's force was supported by 300 civilian auxiliaries and local police. After two days of heavy fighting most of the city had fallen to the insurrectionists and the surviving federal soldiers had withdrawn to their barracks. Navarro then formally surrendered to Madero. The capture of a key border town at an early stage of the revolution not only enabled the revolutionary forces to bring in weapons and supplies from El Paso, but marked the beginning of the end for the demoralized Diaz regime.[19]

During the subsequent years of the conflict, Villa and other revolutionaries struggled for the control of the town (and income from the Federal Customs House), destroying much of the city during battles in 1911 and 1913. Much of the population abandoned the city between 1914 and 1917. Tourism, gambling, and light manufacturing drove the city's recovery from the 1920s until the 1940s. A series of mayors in the 1940s–1960s, like Carlos Villareal and René Mascareñas Miranda, ushered in a period of high growth and development predicated on the PRONAF border industrialization development program. A beautification program spruced up the city center, building a series of arched porticos around the main square, as well as neo-colonial façades for main public buildings such as the city health clinic, the central fire station, and city hall. The cathedral, built in the 1950s, gave the city center the flavor of central Mexico, with its carved towers and elegant dome, but structural problems required its remodeling in the 1970s. The city's population reached some 400,000 by 1970.

Juárez has grown substantially in recent decades due to a large influx of people moving into the city in search of jobs with the maquiladoras. As of 2014 more technological firms have moved to the city, such as the Delphi Corporation Technical Center, the largest in the Western Hemisphere, which employs over 2,000 engineers. Large slum housing communities called colonias have become extensive.

Juárez has gained further notoriety because of violence[20] and as a major center of narcotics trafficking linked to the powerful Juárez Cartel, and for more than 1000 unsolved murders of young women from 1993 to 2003.

Geography

Climate

Due to its location in the Chihuahuan Desert and high altitude, Ciudad Juárez has a cold desert climate (Köppen: BWk). Seasons are distinct, with hot summers, mild springs and autumns, and cold winters. Summer average high is 35 °C (95 °F) with lows of 21 °C (70 °F). Winter highs average 14 °C (57 °F) with lows of 0 °C (32 °F). Rainfall is scarce and greater in summer. Snowfalls occur occasionally (about 4 times a year), between November and March. On December 26/27, 2015, parts of the city received 40 cm (16 in) of snow within a 24-hour period beating the previous record of 28 cm (11 in) set in 1951.[21] The record high is 49 °C (120 °F) and the record low is −23 °C (−9 °F).

| Climate data for Ciudad Juárez (Downtown), elevation: 1,135 metres (3,724 ft), 1971-2001 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.0 (82.4) |

30.0 (86.0) |

33.0 (91.4) |

39.0 (102.2) |

42.0 (107.6) |

49.0 (120.2) |

44.0 (111.2) |

41.5 (106.7) |

41.0 (105.8) |

38.0 (100.4) |

30.1 (86.2) |

34.0 (93.2) |

49.0 (120.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.7 (56.7) |

16.9 (62.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

31.6 (88.9) |

35.6 (96.1) |

35.5 (95.9) |

34.6 (94.3) |

31.1 (88.0) |

25.8 (78.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

25.6 (78.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.8 (42.4) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.7 (53.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.9 (78.6) |

27.5 (81.5) |

26.6 (79.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

10.6 (51.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

17.0 (62.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.9 (28.6) |

0.0 (32.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

15.7 (60.3) |

9.1 (48.4) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −23.0 (−9.4) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 7.7 (0.30) |

11.5 (0.45) |

9.9 (0.39) |

1.1 (0.04) |

4.9 (0.19) |

11.0 (0.43) |

58.3 (2.30) |

41.1 (1.62) |

36.4 (1.43) |

16.4 (0.65) |

9.3 (0.37) |

12.8 (0.50) |

220.4 (8.68) |

| Average rainy days | 2.07 | 2.42 | 2.4 | 0.46 | 1.14 | 2.26 | 6.85 | 4.78 | 3.92 | 2.71 | 1.78 | 1.78 | 32.57 |

| Average snowy days | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: SMN[22] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meoweather.com (Snowy days)[23] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Ciudad Juárez has many affluent neighborhoods, such as Campestre, Campos Elíseos, and Misión de Los Lagos. Other neighborhoods, including Anapra, Chaveña, and Anáhuac, would be considered more marginal, while the remaining neighborhoods in Juárez represent the middle- to working-class, for example, Infonavit, Las Misiones, Valle de Juárez, Lindavista, Altavista, Guadalajara, Galeana, Flores Magón, Mariano Escobedo, Los Nogales, and Independencia.

Demographics

%252C_June_2016.jpg.webp)

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 789,522 | — |

| 1995 | 995,770 | +26.1% |

| 2000 | 1,187,275 | +19.2% |

| 2005 | 1,301,452 | +9.6% |

| 2010 | 1,321,004 | +1.5% |

| 2013 | 1,506,198 | +14.0% |

| [24] | ||

Between the 1960s and 1990s, Juárez saw a high level of population growth due in part to the newly established maquiladoras. The end of the Bracero Program also brought workers back from border cities in the U.S. through Ciudad Juárez, contributing to the growing number of citizens.[25]

The average annual growth in population over a 10-year period [1990–2000] was 5.3%.[26] According to the 2010 population census, the city had 1,321,004 inhabitants, while the municipality had 1,332,131 inhabitants. During the last decades the city has received migrants from Mexico's interior, some figures state that 32% of the city's population originate outside the state of Chihuahua, mainly from the states of Durango (9.9%), Coahuila (6.3%), Veracruz (3.7%) and Zacatecas (3.5%), as well as from Mexico City (1.7%).[26] Though most new residents are Mexican, some also immigrate from Central American countries, such as Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua.

However, a March 2009 article noted there has been a mass exodus of people who could afford to leave the city due to the ongoing violence from the Mexican Drug War. The article quoted a city planning department estimate of over 116,000 abandoned homes, which could roughly be the equivalent of 400,000 people who have left the city due to the violence.[27] A September 2010 article in The Guardian said of Ciudad Juárez: "About 10,670 businesses – 40% of the total – have shut down. A study by the city's university found that 116,000 houses have been abandoned and 230,000 people have left."[28]

Government

The city is governed by a municipal president and an 18-seat council. The president is Armando Cabada Alvidrez, who won as an Independent candidate in 2016. Six national parties are represented on the council: the PRI, the National Action Party, Ecologist Green Party of Mexico, Party of the Democratic Revolution, Labor Party and the New Alliance Party.[29]

Crime and safety

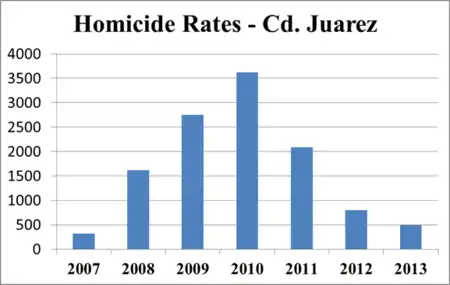

Violence towards women in the municipality increased dramatically between 1993 and the mid-2000s,[30] with approximately 370 girls and women murdered[31] and at least 400 women reported missing.[30] Escalating turf wars between the rival Juárez and Sinaloa Cartels led to increasingly brutal violence in the city beginning in 2007.

In 2012, the Juárez police department dismissed approximately 800 officers in an effort to clean up corruption within its ranks.[32] Recruitment goals set by the department called for the force to more than double.[33] In 2009, a vigilante group calling itself Juárez Citizens Command threatened to put a stop to all the perpetrators of violence if the government continued to fail to curb the violence in the city.[34] Government officials expressed concern that such vigilantism would contribute to further instability and violence.[35]

In 2008, General Moreno and the Third Infantry Company took over the fight against the cartels in town. They were removed in 2009, with the general and 29 of his associates now in custody and awaiting trial for charges of murder and civil rights violations.[36] [37]

In response to increasing violence in the city, the presence of the Mexican Armed Forces and Federal Police has almost doubled. By August 2009 there were more than 7500 soldiers augmented by an expanded and highly restaffed municipal police force.[38]

As of January 2013, Juárez's murder rate placed #37 of the highest reported in the world, at 38 murders per 100,000 inhabitants.[39] This marked a decrease of 70% from 2008, when the rate was 130 murders per 100,000 inhabitants, ranking #1 in the statistic and exceeding second-place Caracas's statistic of 96 murders per 100,000 inhabitants by 35% for the same period.[40] Journalist Charles Bowden, in an August 2008 GQ article, wrote that multiple factors, including drug violence, government corruption and poverty, led to a dispirited and disorderly atmosphere that permeated the city.[20][41]

Crime reduction

After the homicide rates escalated to the point of making Ciudad Juárez the most violent city in the world, violent crime began to decline in the early 2010s.[42] In 2012, homicides were at their lowest rate since 2007 when drug violence flared between the Sinaloa and Juárez Cartel.[43] That trend has continued in 2015 with 300 homicides reported, the lowest number since 2006.[44] Explanations for the rapid decline in violence include the Sinaloa Cartel's success in defeating its rivals,[45] as well as federal, state and local government efforts to combat crime and improve the city's quality of life.

The cause of the reduction in crime is the subject of speculation. One theory attributes it to deals the rival gangs made to coexist once the federal police were withdrawn in 2011. Another holds that a more powerful trafficking network, such as Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman's Sinaloa cartel, might have moved in and restored a kind of "order among thieves."[46] Others attribute it to the end of the cartel war between Juárez and Sinaloa,[47] the arrest or dismissal of many policemen with cartel ties,[48] resolutions reached by liaisons between government and a group of local leaders called "La Mesa de Seguridad y Justicia",[49] and the creation of an anti-extortion squad to combat extortion inflicted upon local companies.[50] Crime was significantly reduced from 2010 to 2014, with 3,500 homicides in 2010 and 430 in 2014.[51] In 2015, there were only 311 homicides.[49]

The decrease in crime inspired more business in the city. Some citizens who left because of the violence have since returned with their families.[46] Many of them had moved their businesses to El Paso.[52] In addition, U.S companies are investing more in Juárez.[48] Community centers work with victims of crime and teach women how to defend themselves. Citizens have also formed neighborhood watch groups and patrol neighborhoods.[46] "La Fundacion Comunitaria de la Frontera Norte" is giving young people career opportunities and giving people hope.[49] Technology HUB is a startup incubator working to diversify the city's economy and move the regions low-skill manufacturing industry into an innovation cluster.[53] Its economic development projects are in line with the research of University of Berkeley Professor Enrico Moretti. Innovation economies are found to be more adaptive to shifting tech and trade conditions and more resilient to the kind of civil unrest that plagued Ciudad Juarez in the past.[54] City officials have said that they have plans to increase tourism in the city.[48] For example, in April 2015, the city created a new campaign to increase tourism called "Juarez is waiting for you".[48] That same month, U.S. representative Beto O'Rourke visited Juárez to give a speech about how much Juárez has changed for the better.[48] A children's museum was opened in honor of the children who lost their parents during the violent years. Businesses that were closed because of the violence and extortion have reopened in recent years.[50] The city's violence was depicted in the 2015 film Sicario, drawing criticism and calls for a boycott from Juarez mayor Enrique Serrano Escobar, who said the film presented a false and negative image of the city. He said the violence the film depicted was accurate through about 2010, and that the city had made progress in restoring peace.[55][56]

Culture

Notable natives and residents

- Juan Acevedo, professional baseball player[57]

- Miguel Aceves Mejía, singer and actor[58]

- Elizabeth Álvarez, actress

- Norma Andrade, founding member of Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa A.C.

- Antonio Attolini Lack, architect

- Joaquín Cosío, actor and director

- Johnny "J", rapper and main producer of Tupac Shakur

- The Chamanas, band

- Liliana Domínguez, fashion model

- Lince Dorado, wrestler

- Abelardo Escobar Prieto, politician

- José "Fishman" Nájera, wrestler

- Julio Daniel Frías, football player

- Juan Gabriel, singer

- Eddie Guerrero, WWE wrestler

- Gory Guerrero, wrestler

- Vanessa Guzmán, Nuestra Belleza Mexico 1996 and actress

- Paco Lala's, television host

- Tito Larriva, musician

- Francisco Martínez, basketball player

- Karla Martínez, co-host of Despierta America

- Guadalupe Miranda, former mayor

- Luis Montes, football player

- Kitten Natividad, former adult film actress

- Zudikey Rodriguez, sprinter

- Germán "Tin-Tán" Valdés, actor

- Manuel "El Loco" Valdes, comedian

- Ramón Valdez "Don Ramón", actor

- Vanessa Zambotti, Judoka and former Olympian

In popular culture

- Part of the action of the 2015 film Sicario is set in Juárez.[59]

- The Bob Dylan song "Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues" is set in a nightmarish depiction of Juárez.

- Ciudad Juárez and the female homicides which took place there are the inspiration for the city of Santa Teresa in Roberto Bolano's 2004 novel 2666.

- The Way She Spoke is a play by Isaac Gomez based on his interviews with people affected by the femicide in Juárez, Mexico. A First Look at Isaac Gomez's The Way She Spoke Off-Broadway, Playbill, July 19, 2019.

- "Invalid Litter Department," a song by El Paso band At the Drive-In, centers on the murders of women in Ciudad Juárez.[60][61]

- The majority of the events depicted in the 2007 videogame Tom Clancy's GRAW 2 take place in and around the city. This drew the ire of then Mayor Héctor Murguía Lardizábal,who accused the game's publisher (Ubisoft) of "painting a negative picture of his city".[62]

Economy and infrastructure

The El Paso Regional Economic Development Corporation indicated that Ciudad Juárez is the metropolis absorbing "more new industrial real estate space than any other North American city."[63] The Financial Times Group through its publication The Foreign Direct Investment Magazine ranked Ciudad Juárez as the "City of the Future" for 2007–2008.[64] The El Paso–Juárez area is a major manufacturing center. CommScope, Electrolux, Bosch, Foxconn, Flextronics, Lexmark, Delphi, Visteon, Johnson Controls, Toro, Lear, Boeing, Cardinal Health, Yazaki, Sumitomo, and Siemens are some of the foreign companies that have chosen Ciudad Juárez for business operations.[65][66]

The Mexican state of Chihuahua is frequently among the top five states in Mexico with the most foreign investment.[67] Many foreign retail, banking, and fast-food businesses have locations within Juárez.

In the 1990s, traditional brick kilns made up a big part of the economic informal sector. These were typically located in the poorer regions of Juárez. The kilns used open-air fires, where certain materials that were burned generated a lot of air pollution. Along with rapid industrialization, small brick kilns have been a big contributor to the high amount of air pollution in Ciudad Juárez.[68] While the Ciudad Juárez economy has largely been dependent on Maquiladora program, business leaders have undertaken initiatives to upskill and secure the city are larger stake in the global manufacturing economy.[69] Technology Hub is a business incubator that works with regionally based companies, on programs in skill development, and the transition into automation and industry 4.0.[70]

Media

Juárez has four local newspapers: El Diario, El Mexicano, El PM and Hoy. El Norte was a fifth, but it ceased operations on April 2, 2017, following the murder of journalist Miroslava Breach because,[71] the paper explained, the recent killings of several Mexican journalists made the job too dangerous.[72]

Public bus system

The main public transportation system in the city is the public bus system. The public buses run the main streets of Ciudad Juárez throughout the day, costing eight pesos (less than 40 cents) to ride one. Due to the aging current bus fleet being considered potentially outdated, the municipal government is working on replacing the buses with new ones, along with improving the bus stops, such as by equipping them with shade.

The ViveBus bus rapid transit (BRT) system opened to the public in November 2013 with the first route of five planned. The project was made a reality with the collaboration of the local municipal government, the private enterprise of Integradora de Transporte de Juárez (INTRA) as well as other city government agencies. Studies have shown that the current bus system averages 8 mph (13 km/h) while the new system is projected to average 16 mph (26 km/h). The BRT system studies conducted by the Instituto Municipal de Investigacion Y Planeacion project a daily ridership of 40,000.

The first of the five routes opened to users in late 2013 and is officially named Presidencia-Tierra Nueva and has 34 stations distributed along the north to south corridor. The route starts at Avenida Francisco Villa, follows north to Eje Vial Norte-Sur then veers left at Zaragoza Blvd. and ends at Avenida Independencia and the elevated Carretera Federal 2.

Airport

The city is served by Abraham González International Airport, with flights to several Mexican cities. It accommodates national and international air traffic for the city. Nearby El Paso International Airport handles flights to cities within the United States.

International border crossings

The first bridge to cross the Rio Grande at El Paso del Norte was built in the time of New Spain, over 250 years ago, from wood hauled in from Santa Fe.[75] Today, this bridge is honored by the modern Santa Fe Street Bridge, and Santa Fe Street in downtown El Paso.

Several bridges serve the El Paso–Ciudad Juárez area in addition to the Paso Del Norte Bridge also known as the Santa Fe Street Bridge, including the Bridge of the Americas, Stanton Street Bridge, and the Ysleta Bridge also known as the Zaragoza Bridge.

There is also a land crossing at nearby Santa Teresa, New Mexico, and another one, the Tornillo - Guadalupe International Bridge located 50 km southeast of Juarez City.

Light rail

El Paso City Lines operated a streetcar system in Juárez from 1881 until 1974.[76]

Heavy rail

Mexico North Western Railway's subsidiary operation, the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad, extended into the US at El Paso, Texas but no longer operates passenger rail.[77]

Education

According to the latest estimates, the literacy rate in the city is in line with the national average: 97.3% of people above 15 years old are able to read and write.[26]

Juárez has about 20 institutions of higher learning . The largest ones are among the followign: 1. The Instituto Tecnológico de Ciudad Juárez (ITCJ), founded in 1964, became the first public institution of higher education in the city. 2. The Autonomous University of Ciudad Juárez (Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, UACJ), founded in 1968, is the largest university in the city. It has several locations inside of the city including the Institute of Biomedical Sciences (Instituto de Ciencias Biomédicas, ICB), the Institute of Social and Administrative Sciences (Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Administrativas, ICSA), the Institute of Architecture, Design and Art (Instituto de Arquitectura, Diseño y Arte, IADA), the Institute of Engineering and Technology (Instituto de Ingeniería y Tecnología, IIT) and the University City (Ciudad Universitaria, CU) located in the southern part of Ciudad Juárez. The IADA and IIT share the same location appearing to be a single institute where the students from both institutes share facilities as buildings or classrooms with the exception of the laboratories of Engineering and the laboratories of Architecture, Design and Arts. The UACJ also has spaces for Fine Arts and Sports.These latter services are considered among the best because they recluse nearly 30,000 participants in sports such as swimming, racquetball, basketball and gymnastics, and arts such as Classical Ballet, Drama, Modern Dance, Hawaiian and Polynesian Dances, Folk dance, Music and Flamenco. 3. The Faculty of Political and Social Sciences of the Autonomous University of Chihuahua (Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, UACH) which has delivered 70% of the city's media and news crew, is located in the city. 4. The local campuses of the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (ITESM) The Monterrey Institute of Technology opened its campus in 1983. It is ranked as "third best" among other campuses of the institution, after the Garza Sada campus in Monterrey and the Santa Fe campus in Mexico City.. Technology Hub Juarez offers after school coding program, Kids 2 Code[78] and is home to Fab Lab Juarez, a facility training people of all ages in the use of 3D printers, laser cutters, CNC routers and prototyping technology.[79] 5. The campus of the Autonomous University of Durango (UAD) 6. The Universidad Interamericana del Norte Archived September 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine 7. Universidad Regional del Norte 8. Escuela Superior de Psicologia A.C. 9. Universidad Tecnológica del Paso del Norte

References

- "Juárez". Catálogo de Localidades. Secretaría de Desarrollo Social (SEDESOL). Archived from the original on April 12, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- "The El Paso Regional Economic Development Corporation". September 18, 2013. Archived from the original on September 18, 2013.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 402.

- "History of Ciudad Juárez". El Paso County Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 9, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- Lisa Chamberlain (March 28, 2007). "2 Cities and 4 Bridges Where Commerce Flows". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- "The Borderplex Alliance". El Paso Regional Economic Development Corporation. 2013. Archived from the original on September 18, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- El Paso Texas. Community profile 2008 Archived May 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico - fDi City of the Future 2007 / 2008". Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- George D. Torok, From the Pass to the Pueblos, Sunstone Press, Santa Fe, Dec 1, 2011

- Harris 2009, p. 1.

- Harris 2009, p. 14.

- Harris 2009, p. 15.

- Hampton 1910.

- van Wyk 2003, pp. 440–446.

- Harris 2009, p. 16.

- Hammond 1935, pp. 565-66.

- Harris 2009, p. 213.

- Harris 2004, p. 26.

- Aitkin, Ronald (1969). Mexico 1910-20. Macmillan & Co. pp. 85–90.

- "Human heads sent to Mexico police", BBC News, October 21, 2008. Accessed March 5, 2009

- "El norte de México vive una emergencia por el frío; nevada histórica paraliza Juárez". SinEmbargo. Archived from the original on December 31, 2015. Retrieved December 28, 2015.

- "Servicio Meteorologico Nacional: Normales Ciudad Juarez 1971–2001" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on September 6, 2010. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- "Meoweather: Ciudad Juárez average weather by month". Archived from the original on December 20, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- "Chihuahua (Mexico): State, Major Cities & Towns - Population Statistics in Maps and Charts". Citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on June 28, 2018. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- Boudreaux, Corrie. "Public Memorialization and the Grievability of Victims in Ciudad Juárez". Social Research. 83 (2).

- Coronado, Roberto; Lucinda Vargas (2001). "Economic Update on El Paso del Norte" (PDF). Business Frontier (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 3, 2008. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- Casey, Nicholas (March 20, 2010). "Cartel Wars Gut Juárez, a Onetime Boom Town". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- Mexican Drug War: The New Killing Fields Archived February 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, September 3, 2010. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- "Index of councilors" (in Spanish). Gobierno Municipal de Juárez. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- Sarriya, Nidya (August 3, 2009). "Femicides of Juárez: Violence Against Women in Mexico". Council on Hemispheric Affairs. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Mexico: Justice fails in Ciudad Juarez and the city of Chihuahua". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- Kocherga, Angela (December 7, 2012). "As murders plummet in Juarez, controversial police chief earns praise". WFAA.com. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- Balderrama, Monica (September 10, 2008). "Juárez Police Department To Dismiss Third Of Force". KFOXTV.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- Borunda, Daniel. "Juarez vigilante group claims it will kill one criminal every 24 hours". El Paso Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- Borunda, Daniel. "Vigilante group sets deadline for Juárez". El Paso Times. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- Booth, William (December 10, 2012). "The Americas". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 23, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- Figueroa, Lorena (April 29, 2016). "Mexican general gets 52 years in torture, death". El Paso Times.

- "Mayor of violence-torn Juarez: 'We're at turning point'". cnn.com/world. Cable News Network. August 31, 2009. Archived from the original on December 15, 2009. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- "The 50 Most Violent Cities In The World". Business Insider UK. November 10, 2014. Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- NAT/AKM (August 27, 2009). "Mexican city world's murder capital". Press TV. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- Bowden, Chris (July 2008). "Mexico's Red Days". GQ. GQ.com, Condé Nast Digital: 1–6. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2009. p.2 Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, p.3 Archived December 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, p.4 Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, p.5 Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, p.6 Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- "Juarez shedding violent image, statistics show". CNN. 2014. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- Booth, William (August 20, 2012). "In Mexico's Murder City the war appears over". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- "Termina 2015 con 300 homicidios; disminuye violencia en 23% del 2014". Juarez Noticias. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- Vulliamy, Ed (19 July 2015). Has ‘El Chapo’ turned the world's former most dangerous place into a calm city? Archived July 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. The Observer.

- Times, Los Angeles (May 4, 2014). "In Mexico, Ciudad Juarez reemerging from grip of violence". latimes.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- Nick Valencia. "After years of violence, 'life is back' in Juarez". Cnn.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- Nick Valencia. "After years of violence, 'life is back' in Juarez". CNN. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- Fern, Miguel; CEO, ez; Transtelco (February 17, 2016). "A New Era in Ciudad Juarez | Huffington Post". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on November 14, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- "Once the World's Most Dangerous City, Juárez Returns to Life". May 13, 2016. Archived from the original on October 3, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- "Despite Violence, Juárez Gets Ready for Pope, Showcases Progress". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- "The Violence Subsides, And Revelers Return To Juarez". NPR.org. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- "Looking for tech innovators in Mexico's Ciudad Juarez". Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- O'Toole, Kathleen (June 10, 2013). "Enrico Moretti: The Geography of Jobs". Stanford. Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- Nájar, Alberto (October 7, 2015). "¿Por qué la película "Sicario" enoja tanto a Ciudad Juárez?" [Why does the movie "Sicario" anger Ciudad Juárez so much?] (in Spanish). BBC. BBC Mundo. Archived from the original on November 14, 2015. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- Burnett, Victoria (October 11, 2015). "Portrayal of Juárez in 'Sicario' Vexes Residents Trying to Move Past Dark Times". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- Inc., Baseball Almanac. "Juan Acevedo Baseball Stats by Baseball Almanac". Archived from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- Jornada, La. "Murió ayer Miguel Aceves Mejía, máximo exponente del falsete - La Jornada". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- Guerrasio, Jason. "One of the most thrilling scenes from 'Sicario' almost didn't get made". Business Insider. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8wR1MVdDmUA

- "Intravenously polite it was the walkie-talkies / That had knocked the pins down / As their shoes gripped the dirt floor / In the silhouette of dying". Genius. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- The Roberto Bolaño book "2666" documents the femicide epidemic and murders of women in Ciudad Juárez.

- "Mexican mayor slams GRAW2". GameSpot. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- 2 Cities and 4 Bridges Where Commerce Flows Archived June 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, March 28, 2007.

- fDi Intelligence – Your source for foreign direct investment information – fDiIntelligence.com Archived April 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Fdimagazine.com. Retrieved on April 30, 2011.

- The World of Manufacturing Archived July 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Industry Today. Retrieved on April 30, 2011.

- "Factory Workers In Juárez Unionize For Higher Pay, Better Working Conditions". Fronteras Desk. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- Mexico's Maquila Online Directory 2008, Fifth edition, p. 7, Servicio Internacional de Información.

- Blackman, A.; Bannister, G. "Pollution Control in the Informal Sector: The Ciudad Juarez Brickmakers' Project". Natural Resources Journal. 37 (4).

- Thompson, Simon. "Reporter". American Public Media: Marketplace morning report. American Public Media. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- "Technology Hub media". Technology Hub. Technology Hub. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- "El periódico Norte de Ciudad Juárez cierra por inseguridad" [The Norte newspaper of Ciudad Juárez closes due to the lack of security]. El Universal (in Spanish). April 2, 2017. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- "Mexican Newspaper Shuts Down, Saying It Is Too Dangerous to Continue". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 4, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- "jrznoticias".

- "El Diario".

- Paul Horgan, Great River: The Rio Grande in North American History. Volume 1, Indians and Spain. Vol. 2, Mexico and the United States. 2 Vols. in 1, 1038 pages – Wesleyan University Press 1991, 4th Reprint, ISBN 0-8195-6251-3

- "History". www.sunmetro.net.

- "EL PASO SOUTHERN RAILWAY | The Handbook of Texas Online| Texas State Historical Association (TSHA)". Tshaonline.org. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- Sierra, Mariana. "Journalist". Borderzine. Borderzine. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- "Fab Lab Juarez". Fab Lab Juarez. Fablabs.io. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

Further reading

- Caballero, Raymond (2015). Lynching Pascual Orozco, Mexican Revolutionary Hero and Paradox. Create Space. ISBN 978-1514382509.

- Hammond, John Hays (1935). The Autobiography of John Hays Hammond. New York: Farrar & Rinehart. ISBN 978-0-405-05913-1.

- Hampton, Benjamin B (April 1, 1910). "The Vast Riches of Alaska". Hampton's Magazine. 24 (1).

- Harris, Charles H. III; Sadler, Louis R. (2009). The Secret War in El Paso: Mexican Revolutionary Intrigue, 1906-1920. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-4652-0.

- Harris, Charles H. III; Sadler, Louis R. (2004). The Texas Rangers And The Mexican Revolution: The Bloodiest Decade. 1910–1920. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-3483-0.

- Oscar J. Martínez. Ciudad Juárez: Saga of a Legendary Border City. University of Arizona Press, 2018. ISBN 978-0-8165-3721-1

- van Wyk, Peter (2003). Burnham: King of Scouts. Victoria, B.C., Canada: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-0901-0.

External links

Ciudad Juárez travel guide from Wikivoyage

Ciudad Juárez travel guide from Wikivoyage- (in Spanish) Official webpage of Juárez

- (in English) webpage of Juárez border bridge times

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ciudad Juárez. |