Climate change in Russia

Climate change in Russia is the changes in Russia's climate due to human caused global warming. This causes several effects, such as permafrost melting and more wildfires. Adaptation to climate change is difficult.

Effects of climate change on Russia

IPCC

According to IPCC (2007), climate change affected temperature increase which is greater at higher northern latitudes in many ways. For example, agricultural and forestry management at Northern Hemisphere higher latitudes, such as earlier spring planting of crops, higher frequency of wildfires, alterations in disturbance of forests due to pests, increased health risks due to heat-waves, changes in infectious diseases and allergenic pollen and changes to human activities in the Arctic, e.g. hunting and travel over snow and ice. From 1900 to 2005, precipitation increased in northern Europe and northern and central Asia. Recently these have resulted in fairly significant increases in GDP. Changes may affect inland flash floods, more frequent coastal flooding and increased erosion, reduced snow cover and species losses.[1]

Permafrost

Permafrost is soil which has been frozen for two or more years. In most Arctic areas it is from a few to several hundred metres thick. Permafrost thawing may be a serious cause for concern. It is believed that carbon storage in permafrost globally is approximately 1600 gigatons; equivalent to twice the atmospheric pool. Protecting peatlands from drainage and clearance slows down the rate of greenhouse gases and gives benefits for biodiversity.[2]

Thawing of permafrost soils releases methane. Methane has 25 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide. Recent methane emissions of the world's soils were estimated between 150 and 250 million metric tons (2008).[3] Estimated annual net methane emission rates at the end of the 20th century for the northern region was 51 million metric tons. Net methane emissions from permafrost regions north included 64% from Russia, 11% from Canada and 7% from Alaska (2004). The business-as-usual scenarios estimate the Arctic methane emissions from permafrost thawing and rising temperatures to range from 54 to 105 million metric tons of methane per year (2006).[3]

Thawing permafrost represents a threat to industrial infrastructure. In May 2020 thawing permafrost at Norilsk-Taimyr Energy's Thermal Power Plant No. 3 caused an oil storage tank to collapse, flooding local rivers with 21,000 cubic metres (17,500 tonnes) of diesel oil.[4][5] The 2020 Norilsk oil spill has been described as the second-largest oil spill in modern Russian history.[6]

Wildfires

According to IPCC, higher temperatures may increase the frequency of wildfires.[1] In Russia, this includes the risk of peatland fires. Peat fire emissions may be more harmful to human health than forest fires. According to Wetlands International the 2010 Russian wildfires were mainly 80–90% from dewatered peatlands. According to UN dewatered bogs cause 6% of human global warming emissions.[7] Moscow air was filled with peat fire emissions in July 2010 and regionally visibility was below 300 metres.[8]

Indigenous lifestyle

Climate change has impacted the traditional lifestyle of the indigenous people of Russia's Far North. Around 2.5 million people live in the Arctic zone. The majority of Russia's indigenous people are located in the Arctic and Siberian regions.[9]

People of Siberia and Far East territories have depended on climate for many centuries for herding and fishing. Due to frequent weather thaws, reindeer have more limited access to lichens because ice layers formed on the ground, threatening traditional reindeer herding of Sami and Nenet people. Researchers have noticed that even small climate changes affect the nomadic life of Nenets.[10] Climate change has also provoked a reduction of marine animals, damaging traditional fisheries.[11]

The Center for the Support of Indigenous Peoples of the North has noted that Russia lacks a program for calculating the possible impact of climate change on indigenous zones. Many environmental Indigenous and Environmental Movements have been declared as foreign agents by the Russian Federation.[9]

Greenhouse gas emissions

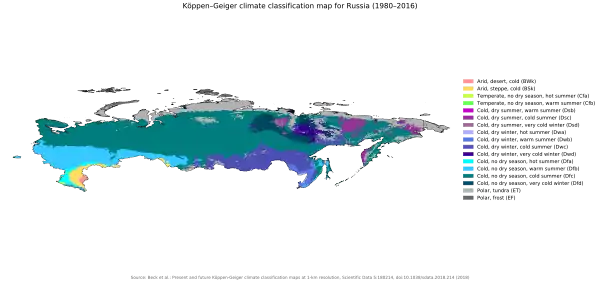

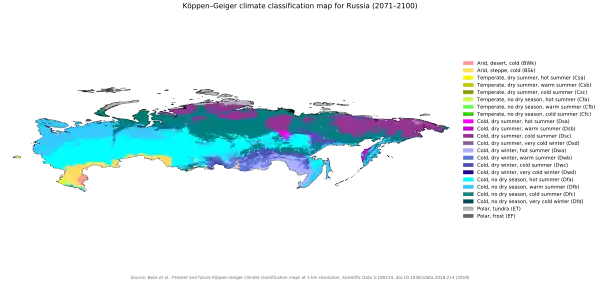

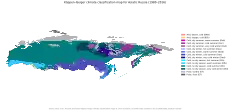

Present and future climate maps

See also

References

- IPCC Working group III fourth assessment report, Summary for Policymakers 2007

- The Natural Fix?: The Role of Ecosystems in Climate Mitigation UNEP 2009 page. 20, 55

- Year Book2008, An Overview of Our Changing Environment Archived 1 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations Environment Programme 2008 pages 38–41

- "Diesel fuel spill in Norilsk in Russia's Arctic contained". TASS. Moscow, Russia. 5 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Max Seddon (4 June 2020), "Siberia fuel spill threatens Moscow's Arctic ambitions", Financial Times

- Ivan Nechepurenko (5 June 2020), "Russia Declares Emergency After Arctic Oil Spill", The New York Times

- turvesuot liekeissä talveen asti yle 12.8.2010

- Venäjän metsäpalot tukaloittavat moskovalaisten elämää yle 26 July 2010

- Stambler, Maria (31 August 2020). "The Impact of Climate Change on Indigenous Peoples Has Received Little Attention in Russia". Climate Scorecard. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- "Reindeer and their nomadic herders face climate change | DW | 04.08.2020". Welle (www.dw.com). Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Scollon, Michael (28 November 2020). "At Risk: Russia's Indigenous Peoples Sound Alarm On Loss Of Arctic, Traditional Way Of Life". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. RadioFreeEurope. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- "Summary of GHG Emissions for Russian Federation" (PDF). UNFCCC.

- "BROWN TO GREEN: THE G20 TRANSITION TO A LOW-CARBON ECONOMY | 2017" (PDF). Climate Transparency.

- Sampedro, Jon; Smith, Steven J.; Arto, Iñaki; González-Eguino, Mikel; Markandya, Anil; Mulvaney, Kathleen M.; Pizarro-Irizar, Cristina; Van Dingenen, Rita (1 March 2020). "Health co-benefits and mitigation costs as per the Paris Agreement under different technological pathways for energy supply". Environment International. 136: 105513. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2020.105513. ISSN 0160-4120.