Combat vehicle

A combat vehicle, also known as a ground combat vehicle, is a self-propelled, weaponized military vehicle used for combat operations in mechanized warfare. Combat vehicles can be wheeled or tracked.

History

Ancient

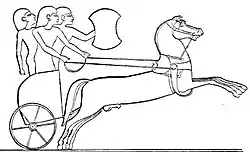

The chariot is a type of carriage using animals (almost always horses)[1] to provide rapid motive power. Chariots were used for war as "battle taxis" and mobile archery platforms, as well as other pursuits such as hunting or racing for sport, and as a chief vehicle of many ancient peoples, when speed of travel was desired rather than how much weight could be carried. The original chariot was a fast, light, open, two-wheeled conveyance drawn by two or more horses that were hitched side by side. The car was little more than a floor with a waist-high semicircular guard in front. The chariot, driven by a charioteer, was used for ancient warfare during the bronze and the iron ages. Armor was limited to a shield.

Design

Automation

The automation of human tasks endeavors to reduce the required crew size with improvements in robotics. Enhancements to automation can help achieve operational effectiveness with a smaller, more economical, combat vehicle force.[2] The automation of combat vehicles has proved to be difficult due to the time latency between the operator controlling the vehicle and the signal being received. Unlike air forces, ground forces must navigate the terrain and plan around obstacles. The rapid tactical implications of operating a weaponized vehicle in a combat environment are great.[3]

Countermeasures

Use of titanium armor on combat vehicles is increasing. The use of titanium can lighten the vehicle's weight.[4]

Appliqué armor can be quickly applied to vehicles and has been utilized on the U.S. Army's M8 Armored Gun System.[4]

- Fire suppression

Contemporary combat vehicles may incorporate a fire-suppression system to mitigate damage from fire. Systems can be employed in the engine and crew compartments and portable systems may be mounted inside and outside the vehicle as well.

Automatic fire suppression systems activate instantaneously upon the detection of fire and have been shown to significantly improve crew survivability. Halon fire suppression systems quickly inundate an affected fire breach with a flood of halon to extinguish leaking fuel. Halon remains necessary for crew compartment fire suppression due to space and weight constraints, and toxicity concerns. Nitrogen systems take up about twice as much space as a comparable halon unit. Germany uses this system as a replacement for its halon system. Some systems, such as Germany's previous extinguisher, have a second shot of suppressant to mitigate re-ignition or the effects of a second hit.[5]

Though not as instantaneous, portable crew-operable extinguishers are also used inside and outside the vehicle. Typically, portable extinguishers use a CO2 agent instead of the halon agents used in the past. CO2 can become lethal to vehicle occupants if it accumulates into a deadly concentration. The U.S. Army has adopted a replacement formula consisting of 50% water, 50% potassium acetate. Alternatives such as powder formulas also exist.[6]

Crew

Hygiene upkeep is difficult when operating a combat vehicle.[7]

Mobility

Tracked combat vehicles are suited for heavy combat and rough terrain. Wheeled combat vehicles offer improved logistical mobility and optimized speeds on smooth terrain.

Silent watch is becoming an increasingly important combat vehicle application.[8] It is a role that requires that all mission requirements be met while keeping acoustic and infrared signature levels to a minimum. For this reason, silent watch often requires the vehicle to operate without use of the main engine and sometimes even auxiliary engines. Many modern combat vehicles often have electronic equipment that cannot be supported solely with auxiliary batteries alone. Auxiliary fuel cells are a potential solution for covert operations.[8]

Networking

Force trackers are not as prevalent as in the air force but are still essential components of combat vehicles.[9][10]

In the mid-'90s, U.S. weapon developers envisioned a sophisticated communication network where positions of enemy and friendly forces could be relayed to command vehicles and other friendly vehicles. Friendly vehicles could transmit enemy positions to friendly combat vehicles in combat range for efficient annihilation of the enemy. Logistics support could also monitor front-line combat vehicle fuel and ammunition statuses and move in to resupply depleted vehicles.[11]

References

- There were rare exceptions to the use of horses to pull chariots, for instance the lion-pulled chariot described by Plutarch in his "Life of Antony".

- Reducing the logistics burden for the Army after next: doing more with less. National Academies Press. 1999. p. 77. ISBN 9780309173322. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- Ratner, Daniel; Ratner, Mark A. (2004). Nanotechnology and Homeland Security: New Weapons for New Wars. Prentice Hall/PTR. p. 58. ISBN 0-13-145307-6. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- Jonathan S. Montgomery; Martin G.H. Wells; Brij Roopchand; James W. Ogilvy (1997). "Low-Cost Titanium Armors for Combat Vehicles". The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- UNEP 1998 assessment report of the Halons Technical Options Committee. UNEP/Earthprint. 1999. p. 132. ISBN 92-807-1729-4. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- Report of the Technology and Economic Assessment Panel: May 2006 : progress report. UNEP/Earthprint. 2006. pp. 103–104. ISBN 92-807-2636-6. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- Clancy, Tom; Franks, Fred Jr.; Koltz, Tony (2004). Into the Storm: A Study in Command. Penguin. p. 58. ISBN 0-425-19677-1. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- http://moab.eecs.wsu.edu/~pedrow/classes/ee415/Fall_2005/Refereed%20Papers/paper2_cobalt.pdf%5B%5D

- Al Ries; Laura Ries (2005). The origin of brands: how product evolution creates endless possibilities for new brands. HarperCollins. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-06-057015-6. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- G.J. Michaels (2008). Tip of the Spear: U.S. Marine Light Armor in the Gulf War. Naval Institute Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-59114-498-4. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- Commercial multimedia technologies for twenty-first century army battlefields: a technology management strategy. National Academies Press. 1995. p. 64. ISBN 0-309-05378-1. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- Police analysis and planning for homicide bombings: prevention, defense, and response. Charles C Thomas Publisher. 2007. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-398-07719-8. Retrieved 14 June 2011.