Constitutional Court of Thailand

The Constitutional Court of the Kingdom of Thailand (Thai: ศาลรัฐธรรมนูญ, RTGS: San Ratthathammanun, pronounced [sǎːn rát.tʰā.tʰām.mā.nūːn]) is an independent Thai court created by the 1997 Constitution with jurisdiction over the constitutionality of parliamentary acts, royal decrees, draft legislation, as well as the appointment and removal of public officials and issues regarding political parties. The current court is part of the judicial branch of the Thai national government.

| The Constitutional Court of the Kingdom of Thailand ศาลรัฐธรรมนูญ | |

|---|---|

| Established | 11 October 1997 |

| Location | Chaeng Watthana Government Complex, Group A, No. 120, Village 3, Chaeng Watthana Road, Thung Song Hong Subdistrict, Lak Si, Bangkok |

| Authorized by | Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, Buddhist Era 2560 (2017) |

| Number of positions | One president, eight judges |

| Annual budget | 223.7 million baht (FY2019) |

| Website | constitutionalcourt |

| President of the Court | |

| Currently | Worawit Kangsasitiam |

| Since | 1 April 2020 |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Thailand |

|

|

|

|

The court, along with the 1997 Constitution, was dissolved and replaced by a Constitutional Tribunal in 2006 following the 2006 Thai coup d'état. While the Constitutional Court had 15 members, seven from the judiciary and eight selected by a special panel, the Constitution Tribunal had nine members, all from the judiciary.[1] A similar institution, consisting of nine members, was again established by the 2007 Constitution.

The Constitutional Court has provoked much public debate, both regarding the court's jurisdiction and composition as well as the initial selection of justices. A long-standing issue has been the degree of control exerted by the judiciary over the court.

The decisions of the court are final and not subject to appeal. Its decisions bind every state organ, including the National Assembly, the Council of Ministers, and other courts.[2]

The various versions of the court have made several significant decisions. These include the 1999 decision that deputy minister of agriculture Newin Chidchop could retain his cabinet seat after being sentenced to imprisonment for defamation; the 2001 acquittal of Thaksin Shinawatra for filing an incomplete statement regarding his assets with the National Anti-Corruption Commission; the 2003 invalidation of Jaruvan Maintaka's appointment as auditor-general; the 2007 dissolution of the Thai Rak Thai political party; the 2014 removal of prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra from office, the dissolution of the Thai Raksa Chart Party before the March 2019 election,[3] and the dissolution of the Future Forward Party in 2020.[4]

The FY2019 budget of the Constitutional Court is 223.7 million baht.[5] As of September 2019, its president is Nurak Marpraneet.[6]

Origins and controversy

Drafting of the 1997 Constitution

The creation of the Constitutional Court was the subject of much debate during the 1996–1997 drafting of the 1997 Constitution of Thailand.[7] Senior judges opposed the concept on the grounds that constitutional and judicial review should remain a prerogative of the Supreme Court and that a Constitutional Court would create a fourth branch of government more powerful than the judiciary, legislature, or executive. Judges stated their fear over political interference in the selection and impeachment of judges. The Constitution Drafting Assembly (CDA) eventually made several concessions regarding the composition and powers of the Court.

Jurisdiction

The constitution did not give the Constitutional Court the authority to overrule a final judgment of the Supreme Court. An affected party, or a court, could request the opinion from the Constitutional Court if it believed a case involved a constitutional issue. The court where the initial action was pending would stay its proceedings until the Constitutional Court issued its decision. Constitutional court decisions would have no retroactive effect on previous decisions of the regular courts.

The constitution also did not give the Constitutional Court the authority to rule on any case in which the constitution did not specifically delegate an agency the power to adjudicate.

Impeachment

The constitution allowed individual justices to be the subject of impeachment proceedings with the vote of one-fourth of the members of the House or with the approval of 50,000 petitioners. A vote of three-fifths of the Senate is required for impeachment. Earlier drafts had required votes of only 10% of the combined House and Senate to call for a vote of impeachment, and votes of three-fifths of the combined parliament to dismiss a justice.

Appointment

The constitution gave the judiciary a strong influence over the composition of the Constitutional Court. Originally, the court was to have nine justices including six legal experts and three political science experts. A panel of 17 persons would propose 18 names from which parliament would elect the nine justices. The panel president would be the president of the Supreme Court, the panel itself would have included four political party representatives. The CDA finally compromised and allowed seven of the justices to be selected by the judiciary, while the remaining eight justices would be selected by the Senate from a list of Supreme Court nominees.

Appointment of the first Constitutional Court

The appointment of the first Constitutional Court following the promulgation of the constitution in 1997 was four month controversy pitting the senate against the Supreme Court.[7] A key issue was the senate's authority to review the backgrounds of judicial nominees and reject nominees deemed inappropriate or unqualified.

Appointment of Amphorn Thongprayoon

After receiving the Supreme Court's list of nominees, the senate created a committee to review the nominees' credentials and backgrounds.[7] On 24 November 1997, the Senate voted to remove the name of Supreme Court Vice-president Amphorn Thongprayoon, on the grounds that his credentials were dubious and on allegations that he had defaulted on three million baht in debt. The Supreme Court was furious, arguing the constitution did not empower the senate to do background checks or to reject Supreme Court nominees. The Supreme Court requested a ruling from the Constitutional Tribunal chaired by the House speaker. On 8 January 1998, in a six to three vote, the Tribunal ruled the Senate did not have the authority to do background checks or reject the Supreme Court's nominees. The Tribunal ruled that the Senate's review powers were limited to examining the records of the nominees and electing half of those nominees for appointment.

Immediately after the Supreme Court filed its request to the Tribunal, Justice Amphorn withdrew his name. After the Tribunal's ruling, the Supreme Court elected justice Jumpol na Songkhla on 9 January 1998 to replace Amphorn. The Senate ignored the Tribunal's ruling and proceeded to review Jumphol’s background and delayed a vote to accept his nomination for seven days so that the Senate could evaluate Jumphol. Finding no problems, the Senate acknowledged his appointment to the court on 23 January 1998.

Appointment of Ukrit Mongkolnavin

The appointment of former Senate and Parliament president Ukrit Mongkolnavin was especially problematic.[7] The Senate had initially elected Ukrit from the list of ten legal specialists nominated by the selection panel, despite claims by democracy activists that Ukrit was unqualified to guard the constitution because he had served dictators while president of parliament under the 1991-1992 military government of the National Peacekeeping Council.

Stung by the Senate rejection of Amphorn Thongprayoon, the two Bangkok Civil Court judges, Sriampron Salikhup and Pajjapol Sanehasangkhom, petitioned the Constitutional Tribunal to disqualify Ukrit on a legal technicality. They argued that Ukrit only had an honorary professorship at Chulalongkorn University, while the 1997 Constitution specifically specifies that a nominee, if not meeting other criteria, must be at least a professor. Echoing the Senate's rejection of Amphorn, the judges also alleged that Ukrit was involved in a multi-million baht lawsuit over a golf course. On 10 January 1998 the tribunal ruled that the judges were not affected parties and therefore they had no right to request a ruling. Nevertheless, the parliament's president invoked his power as chairman of the tribunal to ask the Senate to reconsider Ukrit's nomination.

On 19 January 1998, the Senate reaffirmed Ukrit's qualifications, noting that his professorship was special only because he was not a government official. Under Chulalongkorn's regulations, he had the academic status of a full professor.

This position inflamed activists and the judiciary, and prompted the parliament president on 21 January to invoke his authority under Article 266 of the 1997 Constitution to order the Constitutional Tribunal to consider the issue. On 8 February, in a four to three vote, the tribunal ruled that Ukrit's special professorship did not qualify him for a seat on the Constitutional Court. The tribunal noted that Chulalongkorn's criteria for honorary professorship were different from its criteria for academic professors, as intended by the constitution. The Senate ended up electing Komain Patarapirom to replace Ukrit.

Jurisdiction

Under the 2007 Constitution, the court is competent to address the following:[8]

| # | Matters | Sections of the Constitution allowing their institution | Eligible petitioners | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A petition for a decision as to whether a resolution or regulation of a political party to which the petitioner belongs

|

Section 65, paragraph 3 | A member of the political party in question | Political party |

| 2 | A petition for a decision as to whether any person or political party exercises the constitutional rights and freedoms

|

Section 68 | Any person | Constitutional defence |

| 3 | A petition for a decision as to whether any representative or senator loses his membership by operation of the constitution | Section 91 | At least one-tenth of the existing representatives or senators | Membership |

| 4 | A petition for a decision as to whether a political party resolution terminating any representative's membership in the party

|

Section 106 (7) | The representative in question | Political party |

| 5 | A petition for a decision concerning the constitutionality of a draft organic act having been approved by the National Assembly | Section 141 | The National Assembly | Constitutionality of draft law |

| 6 | A petition for a decision as to whether a draft organic act or act introduced by the council of ministers or representatives bears the principle identical or similar to that which needs to be suppressed | Sections 140 and 149 | The president of the House of Representatives or Senate | Constitutionality of draft law |

| 7 | A petition for a decision as to

|

Section 154 |

|

Constitutionality of draft law |

| 8 | A petition for a decision as to

|

Section 155 |

|

Constitutionality of draft law |

| 9 | A petition for a decision as to whether any motion, motion amendment or action introduced during the House of Representatives, Senate or committee proceedings for consideration of a draft bill on annual expenditure budget, additional expenditure budget or expenditure budget transfer, would allow a representative, Senator or committee member to directly or indirectly be involved in the disbursement of such budget | Section 168, paragraph 7 | At least one-tenth of the existing representatives or senators | Others |

| 10 | A petition for a decision as to whether any minister individually loses his ministership | Section 182 |

|

Membership |

| 11 | A petition for a decision as to whether an emergency decree is enacted against section 184, paragraph 1 or 2, of the Constitution | Section 185 | At least one-fifth of the existing representatives or senators | Constitutionality of law |

| 12 | A petition for a decision as to whether any "written agreement" to be concluded by the executive branch requires prior parliamentary approval because

|

Section 190 | At least one-tenth of the existing representatives or senators | Authority |

| 13 | A petition for a decision as to whether a legal provision to be applied to any case by a court of justice, administrative court or military court is unconstitutional | Section 211 | A party to such case | Constitutionality of law |

| 14 | A petition for a decision as to the constitutionality of a legal provision | Section 212 | Any person whose constitutionally recognised right or freedom has been violated | Constitutionality of law |

| 15 | A petition for a decision as to a conflict of authority between the National Assembly, the Council of ministers, or two or more constitutional organs other than the courts of justice, administrative courts or military courts | Section 214 |

|

Authority |

| 16 | A petition for a decision as to whether any election commissioner lacks a qualification, is attacked by a disqualification or has committed a prohibited act | Section 233 | At least one-tenth of the existing representatives or senators | Membership |

| 17 | A petition for

|

Section 237 in conjunction with section 68 | Any person | Political party |

| 18 | A petition for a decision as to the constitutionality of any legal provision | Section 245 (1) | Ombudsmen | Constitutionality of law |

| 19 | A petition for a decision as to the constitutionality of any legal provision on grounds of human rights | Section 257, paragraph 1 (2) | The National Human Rights Commission | Constitutionality of law |

| 20 | Other matters permitted by legal provisions | Others | ||

Composition

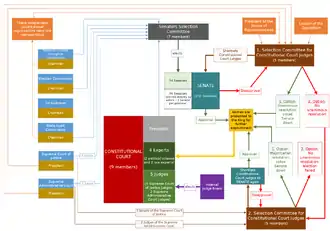

1997 Constitution

The Constitutional Court was modeled after the Constitutional Court of Italy.[9] According to the 1997 Constitution, the Court had 15 members, all serving nine year terms and appointed by the king upon senatorial advice:[10]

- Five were judges of the Supreme Court of Justice (SCJ) and selected by the SCJ Plenum through secret ballot.

- Two were judges of the Supreme Administrative Court (SAC) and selected by the SAC Plenum through secret ballot.

- Five were experts in law approved by the Senate after having been selected by a special panel. Such panel consisted of the SCJ president, four deans of law, four deans of political science, and four representatives of the political parties whose members are representatives.

- Three were experts in political science approved by the Senate after having been selected by the same panel.

2006 Constitution

According to the 2006 Constitution, the Constitutional Tribunal was established to replace the Constitutional Court which had been dissolved by the Council for Democratic Reform. The Tribunal had nine members as follows:[11]

- The SCJ president as president.

- The SAC president as vice-president.

- Five SCJ judges selected by the SCJ plenum through secret ballot.

- Two SAC judges selected by the SAC plenum through secret ballot.

Members of the Tribunal

| Name | Tenure | Basis[12] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romanised | Thai | RTGS | Start | End | Reason for vacation of office | |

| Ackaratorn Chularat | อักขราทร จุฬารัตน | Akkharathon Chularat | 2006 | 2008 | Operation of section 300 of the 2007 Constitution | SAC president |

| Charan Hathagam | จรัญ หัตถกรรม | Charan Hatthakam | 2006 | 2008 | Operation of section 300 of the 2007 Constitution | SAC judge |

| Kitisak Kitikunpairoj | กิติศักดิ์ กิติคุณไพโรจน์ | Kitisak Kitikhunphairot | 2006 | 2008 | Operation of section 300 of the 2007 Constitution | SCJ judge |

| Krairerk Kasemsan, Mom Luang | ไกรฤกษ์ เกษมสันต์, หม่อมหลวง | Krai-roek Kasemsan, Mom Luang | 2006 | 2008 | Operation of section 300 of the 2007 Constitution | SCJ judge |

| Nurak Marpraneet | นุรักษ์ มาประณีต | Nurak Mapranit | 2006 | 2008 | Operation of section 300 of the 2007 Constitution | SCJ judge |

| Panya Thanomrod | ปัญญา ถนอมรอด | Panya Thanomrot | 2006 | 2007 | Retirement from the office of SCJ president | SCJ president |

| Somchai Pongsata | สมชาย พงษธา | Somchai Phongsatha | 2006 | 2008 | Operation of section 300 of the 2007 Constitution | SCJ judge |

| Thanis Kesawapitak | ธานิศ เกศวพิทักษ์ | Thanit Ketsawaphithak | 2006 | 2008 | Operation of section 300 of the 2007 Constitution | SCJ judge |

| Vichai Chuenchompoonut | วิชัย ชื่นชมพูนุท | Wichai Chuenchomphunut | 2006 | 2008 | Operation of section 300 of the 2007 Constitution | SAC judge |

| Viruch Limvichai | วิรัช ลิ้มวิชัย | Wirat Limwichai | 2007 | 2008 | Operation of section 300 of the 2007 Constitution | SCJ president |

2007 Constitution

After the Constitutional Court was abolished by the Council for Democratic Reform and was replaced by the Constitutional Tribunal under the 2006 Constitution, the 2007 Constitution reestablishes the Constitutional Court and makes various changes to it. The Court is back with greater vigour and is also empowered to introduce to the National Assembly the draft laws concerning the Court itself.[13]

Under the 2007 Constitution, the Constitutional Court has nine members, all serving for nine year terms and appointed by the king with senatorial advice:[14]

- Three are SCJ judges and are selected by the SCJ plenum through secret ballot.

- Two are SAC judges and are selected by the SAC plenum through secret ballot.

- Two are experts in law approved by the Senate after having been selected by a special panel. Such panel is composed of the SCJ president, the SAC president, the president of the House of Representatives, the opposition leader and one of the chiefs of the constitutional independent agencies (chief ombudsman, president of the election commission, president of the National Anti-Corruption Commission or president of the State Audit Commission).

- Two are experts in political science, public administration or other field of social science and are approved by the Senate after having been selected by the same panel.

Members of the court

| Name | Tenure | Presidency | Basis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romanised | Thai | RTGS | Start | End | Reason for vacation of office | Start | End | Reason for vacation of office | |

| Jaran Pukditanakul | จรัญ ภักดีธนากุล | Charan Phakdithanakun | 2008[15] | Expert in law[16] | |||||

| Charoon Intachan | จรูญ อินทจาร | Charun Inthachan | 2008[15] | 2013[17] | 2014[18] | Resignation[18] | SAC judge[19] | ||

| Chalermpon Ake-uru | เฉลิมพล เอกอุรุ | Chaloemphon Ek-uru | 2008[15] | Expert in political science[19] | |||||

| Chut Chonlavorn | ชัช ชลวร | Chat Chonlawon | 2008[15] | 2008[15] | 2011[20] | Resignation[20] | SCJ judge[19] | ||

| Nurak Marpraneet | นุรักษ์ มาประณีต | Nurak Mapranit | 2008[15] | SCJ judge[19] | |||||

| Boonsong Kulbupar | บุญส่ง กุลบุปผา | Bunsong Kunbuppha | 2008[15] | SCJ judge[19] | |||||

| Suphot Khaimuk | สุพจน์ ไข่มุกด์ | Suphot Khaimuk | 2008[15] | Expert in political science[19] | |||||

| Wasan Soypisudh | วสันต์ สร้อยพิสุทธิ์ | Wasan Soiphisut | 2008[15] | 2013[21] | Resignation[21] | 2011[20] | 2013[21] | Resignation[21] | Expert in law[21] |

| Udomsak Nitimontree | อุดมศักดิ์ นิติมนตรี | Udomsak Nitimontri | 2008[15] | SAC judge[19] | |||||

| Taweekiat Meenakanit | ทวีเกียรติ มีนะกนิษฐ | Thawikiat Minakanit | 2013[17] | Expert in law[21] | |||||

Key decisions

Unconstitutionality of emergency economic decrees

In its first decision, the Court ruled on the constitutionality of four emergency executive decrees issued by the Chuan government to deal with the Asian financial crisis.[7] The government had issued the decrees in early-May 1998 to expand the role of the Financial Restructuring Authority and the Assets Management Corporation, to settle the debts of the Financial Institutions Development Fund through the issue of 500 billion baht in bonds, and to authorize the ministry of finance to seek 200 billion baht in overseas loans. The opposition New Aspiration Party (NAP) did not have the votes to defeat the bills, and therefore, on the last day of debate, invoked Article 219 of the Constitution to question the constitutionality of an emergency decree.

The NAP argued that since there was no emergency nor necessary urgency (under Article 218(2)), the government could not issue any emergency decrees. Article 219, however, specifically notes the constitutionality of an emergency decree can be questioned only on Article 218(1) concerning the maintenance of national or public safety, national economic security, or to avert public calamity. The government, fearing further economic damage if the decree were delayed, opposed the Court's acceptance of the complaint, as the opposition clearly had failed to cite the proper constitutional clause. The Court wished to set a precedent, however, demonstrating it would accept petitions under Article 219, even if technically inaccurate. Within a day it ruled that it was obvious to the general public that the nation was in an economic crisis, and that the decrees were designed to assist with national economic security in accordance with Article 218(1). The decrees were later quickly approved by Parliament.

The NAP's last minute motion damaged its credibility, and made it unlikely that Article 219 will be invoked unless there is a credible issue and the issue is raised and discussed at the beginning of parliamentary debate, rather than at the last-minute before a vote.

On the other hand, a precedent was established by the Court that it would accept all petitions under Article 219 to preserve Parliament's right to question the constitutionality of emergency executive decrees.

Treaty status of IMF letters of intent

The NAP later filed impeachment proceedings with the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) against prime minister Chuan Leekpai and the minister of finance Tarrin Nimmanahaeminda for violation of the Constitution.[7] The NAP argued that the letter of intent that the government signed with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to secure emergency financial support was a treaty, and that Article 224 of the Constitution stipulated that the government must receive prior consent from Parliament to enter a treaty.

The NACC determined the issue concerned a constitutional interpretation and petitioned the Constitutional Court for an opinion. The Court ruled the IMF letters were not treaties, as internationally defined, because they were unilateral documents from the Thai government with no rules for enforcement or provisions for penalty. Moreover, the IMF itself had worded the letters in a way that stated that the letters were not contractual agreements.

Appointment of Jaruvan Maintaka as auditor-general

On 24 June 2003, a petition was filed with the Constitutional Court seeking its decision on the constitutionality of Jaruvan Maintaka’s appointment by the Senate as auditor-general. Jaruvan was one of three nominees for the position of auditor-general in 2001, along with Prathan Dabpet and Nontaphon Nimsomboon. Prathan received five votes from the eight person State Audit Commission (SAC) while Jaruvan received three votes. According to the constitution, State Audit Commission chairman Panya Tantiyavarong should have submitted Prathan's nomination to the Senate, as he received the majority of votes. However, on 3 July 2001, the SAC chairman submitted a list of all three candidates for the post of auditor-general to the Senate, which later voted to select Khunying Jaruvan Maintaka.

The Constitutional Court ruled on 6 July 2004 that the selection process that led to the appointment of Jaruvan as auditor-general was unconstitutional. The court noted that the constitution empowers the SAC to nominate only one person with the highest number of votes from a simple majority, not three as had been the case. The court stopped short of saying she had to leave her post.[22] However, when the Constitutional Court had ruled on 4 July 2002 that the then Election Commission chairman Sirin Thoopklam's election to the body was unconstitutional, the president of the court noted "when the court rules that the selection [process] was unconstitutional and has to be redone, the court requires the incumbent to leave the post".[23]

Jaruwan refused to resign without a royal dismissal from King Bhumibol Adulyadej. She noted "I came to take the position as commanded by a royal decision, so I will leave the post only when directed by such a decision."[24] The State Audit Commission later nominated Wisut Montriwat, former deputy permanent secretary of the ministry of finance, for the post of auditor-general. The Senate approved the nomination on 10 May 2005. However, King Bhumibol Adulyadej, in an unprecedented move, withheld his royal assent. The National Assembly did not hold a vote to overthrow the royal veto. In October 2005 the Senate rejected a motion to reaffirm her appointment, and instead deferred the decision to the SAC.[25]

On 15 February 2006 the State Audit Commission (SAC) reinstated Auditor-General Khunying Jaruvan Maintaka. Its unanimous decision came after it received a memo from the office of King Bhumibol Adulyadej's principal private secretary, directing that the situation be resolved.[26]

The controversy led many to reinterpret the political and judicial role of the king in Thailand's constitutional monarchy.

Thaksin Shinawatra's alleged conflicts of interest

In February 2006, 28 Senators submitted a petition to the Constitutional Court calling for the prime minister's impeachment for conflicts of interest and improprieties in the sell-off of Shin Corporation under Articles 96, 216 and 209 of the Thai constitution.[27] The Senators said the prime minister violated the Constitution and was no longer qualified for office under Article 209. However, the Court rejected the petition on 16 February, with the majority judges saying the petition failed to present sufficient grounds to support the prime minister's alleged misconduct.

Political parties dissolution following the April 2006 election

Court rejects flawed oath petition

In September 2019, the court rejected a petition lodged by the Ombudsman of Thailand regarding the incomplete oath recited by Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha and his cabinet in July 2019.[28] The prime minister failed to recite the final sentence of the oath which pledges to uphold and abide by the constitution. The court ruled that it was "not in its authority" to make a ruling on the issue, in effect ruling that vows to uphold the constitution are none of the constitutional court's business.[29][30]

Court rules that Prayut not "state official"

The court ruled in September 2019, that General Prayut, on seizing power in May 2014 with no authorization to do so, answering to no other state official, and holding onto his power only temporarily, could not be considered a state official. The ruling bears on Prayut's eligibility to serve as prime minister.[30]

See also

References

- The Nation, Nine Constitution Tribunal members Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, 7 October 2006

- ข้อกำหนดศาลรัฐธรรมนูญว่าด้วยวิธีพิจารณาและการทำคำวินิจฉัย พ.ศ. 2550 - ข้อ 55 วรรค 1 [Constitutional Court Regulations on Procedure and Decision Making, BE 2550 (2007) - regulation 55, paragraph 1] (PDF). Government Gazette (in Thai). Bangkok: Cabinet Secretariat. 124 Part 96 A: 28. 21 December 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- Mérieau, Eugénie (3 May 2019). "The Thai Constitutional Court, a Major Threat to Thai Democracy". International Association of Constitutional Law (IACL). Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "FFP dissolved, executives banned for 10 years". Bangkok Post. 21 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- Thailand's Budget in Brief Fiscal Year 2019 (Revised ed.). Bureau of the Budget. 2018. p. 94. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "President and Judges of the Constitutional Court". The Constitutional Court of the Kingdom of Thailand. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- James R. Klein, "The Battle for Rule of Law in Thailand: The Constitutional Court of Thailand", "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ข้อกำหนดศาลรัฐธรรมนูญว่าด้วยวิธีพิจารณาและการทำคำวินิจฉัย พ.ศ. 2550 [ข้อ 17] [Constitutional Court Regulations on Procedure and Decision Making, BE 2550 (2007), [Regulation 17]] (PDF). Government Gazette (in Thai). Cabinet Secretariat. 124 (96 A): 1. 21 December 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- Andrew Harding, May there be Virtue: ‘New Asian Constitutionalism’ in Thailand, Microsoft Word format and HTML format

- รัฐธรรมนูญแห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย พุทธศักราช ๒๕๔๐ (in Thai). Council of State of Thailand. 14 September 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- รัฐธรรมนูญแห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย (ฉบับชั่วคราว) พุทธศักราช ๒๕๔๙ (PDF) (in Thai). Cabinet Secretariat. 1 October 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ประกาศ ลงวันที่ 1 พฤศจิกายน 2549 [Announcement of 1 November 2006] (PDF) (in Thai). Cabinet Secretariat. 7 November 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- Council of State of Thailand (2007). "Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, Buddhist Era 2550 (2007)". Asian Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

Section 139. An organic law bill may be introduced only by the following...(3) the Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court of Justice or other independent Constitutional organisation by through the President of such Court or of such organizations whom having charge and control of the execution of the organic law.

- องค์ประกอบของศาลรัฐธรรมนูญตามรัฐธรรมนูญแห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย พุทธศักราช 2550. Constitutional Court (in Thai). n.d. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ประกาศแต่งตั้งประธานศาลรัฐธรรมนูญและตุลาการศาลรัฐธรรมนูญ ลงวันที่ 28 พฤษภาคม 2551 [Proclamation on Appointment of President and Judges of the Constitutional Court dated 28 May 2008] (PDF) (in Thai). Cabinet Secretariat. 27 June 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- จรัญ ภักดีธนากุล [Jaran Pukditanakul] (in Thai). DailyNews. 19 May 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ประกาศแต่งตั้งประธานศาลรัฐธรรมนูญและตุลาการศาลรัฐธรรมนูญ ลงวันที่ 21 ตุลาคม 2556 [Proclamation on Appointment of President and Judges of the Constitutional Court dated 21 October 2013] (PDF) (in Thai). Cabinet Secretariat. 31 October 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ผลการประชุมคณะตุลาการศาลรัฐธรรมนูญ วันพุธที่ 21 พฤษภาคม 2557 [Constitutional Court meeting, Wednesday, 21 May 2014] (in Thai). Constitutional Court. 21 May 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- สัจจะไม่มีในหมู่โจร [No honour among thieves] (in Thai). Manager. 27 July 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ประกาศแต่งตั้งประธานศาลรัฐธรรมนูญ ลงวันที่ 26 ตุลาคม 2554 [Proclamation on Appointment of President of the Constitutional Court dated 26 October 2011] (PDF) (in Thai). Cabinet Secretariat. 17 November 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ประกาศคณะกรรมการสรรหาตุลาการศาลรัฐธรรมนูญ ลงวันที่ 5 สิงหาคม 2556 [Announcement of the Constitutional Judge Recruitment Panel dated 5 August 2013] (PDF) (in Thai). Senate of Thailand. n.d. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- Chronology of events in the auditor-general’s deadlock, The Nation 30 August 2005

- The Nation, "Jaruvan again in eye of the storm" Archived 12 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine, 2 June 2006

- Jaruvan waits for royal word, The Nation 9 September 2005

- Senate steers clear of motion on Jaruvan, The Nation, 11 October 2005

- Poll booths 'the decider', Bangkok Post Friday 5 May 2006

- Xinhua, Students submit voters petition to impeach Thai PM, 29 July 2006

- "The Guardian view on Thailand: intimidation can't solve the problem" (Opinion). The Guardian. 20 September 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Bangprapa, Mongkol; Chetchotiros, Nattaya (12 September 2019). "Court rejects oath petition". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- Techawongtham, Wasant (21 September 2019). "Fuzzy logic doing a disservice to nation?" (Opinion). Bangkok Post. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

Further reading

In English

- Dressel, Bjőrn; Khemthong, Tonsakulrungruang (2019). "Coloured Judgements? The Work of the Thai Constitutional Court, 1998–2016". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 49 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/00472336.2018.1479879.

- Dressel, Björn (2010). "Judicialization of politics or politicization of the judiciary? Considerations from recent events in Thailand". The Pacific Review. 23 (5): 671–691. doi:10.1080/09512748.2010.521253.

- Harding, Andrew; Leyland, Peter (2008). "The Constitutional Courts of Thailand and Indonesia: Two Case Studies from South East Asia". J. Comp. L. 3: 118ff. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- McCargo, Duncan (December 2014). "Competing Notions of Judicialization in Thailand". Contemporary Southeast Asia. 36 (3): 417–441. doi:10.1355/cs36-3d. JSTOR 43281303.

- Mérieau, Eugénie (2016). "Thailand's Deep State, Royal Power and the Constitutional Court (1997–2015)". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 46 (3): 445–466. doi:10.1080/00472336.2016.1151917.

- Nolan, Mark (10 October 2012). "Review Essay: The Constitutional System of Thailand: A Contextual Analysis". Australian Journal of Asian Law. 13 (1). SSRN 2159591.

- Takahashi, Toru (7 March 2020). "Thai Constitutional Court leans closer to military amid protests". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

In Thai

- Amorn Raksasat (2000). Charter Court Judges Are Protecting or Destroying the Constitution: A Collection of Comments on Ministership Decision (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Constitution for the People Society. ISBN 9748595323.

- Banjerd Singkaneti (1998). Analysis on Problems of Appointment of Thai Constitutional Court Judges, Taking into Consideration German Theories (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Senate Secretariat General.

- Banjerd Singkaneti (2004). A Collection of Comments on Constitutional Court Decisions and Administrative Court Orders (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Winyuchon. ISBN 9742881324.

- Constitution Court and Recruitment of Constitutional Position Holders under Legal State System (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Nititham. 2006. ISBN 9742033706.

- Constitutional Court Office (2007). An Introduction to the Constitutional Court (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Constitutional Court Office.

- Constitutional Court Office (2007). An Introduction to the Constitutional Tribunal (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Constitutional Court Office.

- Constitutional Court Office (2008). A Decade of the Constitutional Court (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Constitutional Court Office. ISBN 9789747725513.

- Kanin Boonsuwan (2005). Is Our Constitution Dead? (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: From Bookers. ISBN 9749272366.

- Kanin Boonsuwan (2007). What the Country Gets from Ripping the Charter? (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: From Bookers. ISBN 9789747358599.

- Kanit Na Nakhon (2005). Fraudulent Rule of Law in Thai Law (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Winyuchon. ISBN 9742882614.

- Kanit Na Nakhon (2006). Constitution and Justice (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Winyuchon. ISBN 9742884072.

- Kanit Na Nakhon (2007). Ripping the Law: Retroactive Application of Law in Party Dissolution Case (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Winyuchon. ISBN 9789742885779.

- Manit Jumpa (2002). A Study on Constitutional Lawsuits (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Winyuchon. ISBN 9749577116.

- Manit Jumpa (2007). A Comment on Reform of Thai Constitution in 2007 (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University Press. ISBN 9789740319078.

- Noranit Setabutr (2007). Constitutions and Thai Politics (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Thammasat University Press. ISBN 9789745719996.

- Senate Secretariat General (2008). Recruitment and Selection of Constitutional Court Judges under the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, Buddhist Era 2540 (1997) (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Supervision and Examination Bureau, Senate Secretariat General. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- Somyot Chueathai; et al. (2003). Rule of Law and Power to Issue Emergency Decrees: Analysis of Constitutional Court Decision on Enactment of Emergency Decree Excising Telecommunication Business, BE 2546 (2003) (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Winyuchon. ISBN 9745708569.

- Worachet Pakeerut; et al. (2003). Constitutional Court and its Execution of Constitutional Missions (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Winyuchon. ISBN 9749645235.

- Worachet Pakeerut (2003). Constitutional Court Procedure: Comparison between Foreign Constitutional Courts and Thai Constitutional Court (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Winyuchon. ISBN 9749577914.