Copyright Act of 1976

The Copyright Act of 1976 is a United States copyright law and remains the primary basis of copyright law in the United States, as amended by several later enacted copyright provisions. The Act spells out the basic rights of copyright holders, codified the doctrine of "fair use", and for most new copyrights adopted a unitary term based on the date of the author's death rather than the prior scheme of fixed initial and renewal terms. It became Public Law number 94-553 on October 19, 1976 and went into effect on January 1, 1978.[1]

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An Act for the general revision of the Copyright Law, title 17 of the United States Code, and for other purposes |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 94th United States Congress |

| Effective | January 1, 1978 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub.L. 94–553 |

| Statutes at Large | 90 Stat. 2541 |

| Codification | |

| Acts amended | Copyright Act of 1909 |

| Titles amended | 17 (Copyright) |

| U.S.C. sections created | 17 U.S.C. §§ 101-810 |

| U.S.C. sections amended | 44 U.S.C. §§ 505, 2113; 18 U.S.C. § 2318 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| |

History and purpose

Before the 1976 Act, the last major revision to statutory copyright law in the United States occurred in 1909. In deliberating the Act, Congress noted that extensive technological advances had occurred since the adoption of the 1909 Act. Television, motion pictures, sound recordings, and radio were cited as examples. The Act was designed in part to address intellectual property questions raised by these new forms of communication.[2]

Aside from advances in technology, the other main impetus behind the adoption of the 1976 Act was the development of and the United States' participation in the Universal Copyright Convention (UCC) (and its anticipated participation in the Berne Convention). While the U.S. became a party to the UCC in 1955, the machinery of government was slow to update U.S. copyright law to conform to the Convention's standards. Barbara Ringer, the US Register of Copyrights, took an active role in drafting a new copyright act.[3]

In the years following the United States' adoption of the UCC, Congress commissioned multiple studies on a general revision of copyright law, culminating in a published report in 1961. A draft of the bill was introduced in both the House and Senate in 1964, but the original version of the Act was revised multiple times between 1964 and 1976 (see House report number 94-1476). The bill was passed as S. 22 of the 94th Congress by a vote of 97–0 in the Senate on February 19, 1976. S. 22 was passed by a vote of 316–7 in the House of Representatives on September 22, 1976. The final version was adopted into law as title 17 of the United States Code on October 19, 1976 when Gerald Ford signed it. The law went into effect on January 1, 1978. At the time, the law was considered to be a fair compromise between publishers' and authors' rights.

Barbara Ringer called the new law "a balanced compromise that comes down on the authors' and creators' side in almost every instance."[4] The law was almost exclusively discussed in publishers' and librarians' journals, with little discussion in the mainstream press. The claimed advantage of the law's extension of the term of subsisting copyrights was that "royalties will be paid to widows and heirs for an extra 19 years for such about-to-expire copyrights as those on Sherword Anderson's Winesburg, Ohio".[4] The other intent of the extension was to protect authors' rights "for life plus 50 years—the most common term internationally and the one Twain fought for in his lifetime".[4] Further extensions of both term and scope had been desired by some, as outlined in a Time article.[4]

Significant portions of the Act

The 1976 Act, through its terms, displaces all previous copyright laws in the United States insofar as those laws conflict with the Act. Those include prior federal legislation, such as the Copyright Act of 1909, and extend to all relevant common law and state copyright laws.

Subject matter of copyright

Under section 102 of the Act, copyright protection extends to "original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device". The Act defines "works of authorship" as any of the following:

- literary works,

- musical works, including any accompanying words,

- dramatic works, including any accompanying music,

- pantomimes and choreographic works,

- pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works,

- motion pictures and other audiovisual works, and

- sound recordings.[5]

An eighth category, architectural works, was added in 1990.

The wording of section 102 is significant mainly because it effectuated a major change in the mode of United States copyright protection. Under the last major statutory revision to U.S. copyright law, the Copyright Act of 1909, federal statutory copyright protection attached to original works only when those works were 1) published and 2) had a notice of copyright affixed. State copyright law governed protection for unpublished works before the adoption of the 1976 Act, but published works, whether containing a notice of copyright or not, were governed exclusively by federal law. If no notice of copyright was affixed to a work and the work was, in fact, "published" in a legal sense, the 1909 Act provided no copyright protection and the work became part of the public domain. Under the 1976 Act, however, section 102 says that copyright protection extends to original works that are fixed in a tangible medium of expression. Thus, the 1976 Act broadened the scope of federal statutory copyright protection from "published" works to works that are "fixed".

Section 102(b) excludes several categories from copyright protection, partly codifying the concept of idea–expression distinction from Baker v. Selden. It requires that "in no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work."[5]

Music

There are separate copyright protections for musical compositions and sound recordings. Composition copyright includes lyrics and unless self-published, is usually transferred under the terms of a publishing contract. Many record companies will also require that sound recording copyright be transferred to them as part of the terms of an album release, however the owner of the composition copyright is not always the same as the owner of the sound recording copyright.[6]

Exclusive rights

Section 106 granted five exclusive rights to copyright holders, all of which are subject to the remaining sections in chapter 1 (currently, sections 107–122):

- the right to reproduce (copy) the work into copies and phonorecords,

- the right to create derivative works of the original work,

- the right to distribute copies and phonorecords of the work to the public by sale, lease, or rental,

- the right to perform the work publicly (if the work is a literary, musical, dramatic, choreographic, pantomime, motion picture, or other audiovisual work), and

- the right to display the work publicly (if the work is a literary, musical, dramatic, choreographic, pantomime, pictorial, graphic, sculptural, motion picture, or other audiovisual work).[7]

A sixth exclusive right was later included in 1995 by the Digital Performance Right in Sound Recordings Act: the right to perform a sound recording by means of digital audio.

Fair use

Additionally, the fair use defense to copyright infringement was codified for the first time in section 107 of the 1976 Act. Fair use was not a novel proposition in 1976, however, as federal courts had been using a common law form of the doctrine since the 1840s (an English version of fair use appeared much earlier). The Act codified this common law doctrine with little modification. Under section 107, the fair use of a copyrighted work is not copyright infringement, even if such use technically violates section 106. While fair use explicitly applies to use of copyrighted work for criticism, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research purposes, the defense is not limited to these areas. The Act gives four factors to be considered to determine whether a particular use is a fair use:

- the purpose and character of the use (commercial or educational, trans-formative or reproductive, political);

- the nature of the copyrighted work (fictional or factual, the degree of creativity);

- the amount and substantiality of the portion of the original work used; and

- the effect of the use upon the market (or potential market) for the original work.[8]

The Act was later amended to extend the fair use defense to unpublished works. [9]

Term of protection

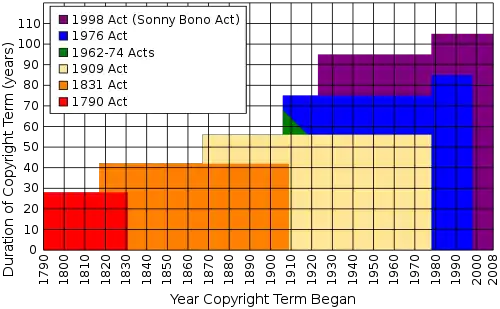

Previous copyright law set the duration of copyright protection at 28 years with a possibility of a 28 year extension, for a total maximum term of 56 years. The 1976 Act, however, substantially increased the term of protection. Section 302 of the Act extended protection to "a term consisting of the life of the author and fifty years after the author's death".[10] In addition, the Act created a static 75-year term (dated from the date of publication) for anonymous works, pseudonymous works, and works made for hire. The extension term for works copyrighted before 1978 that had not already entered the public domain was increased from 28 years to 47 years, giving a total term of 75 years. In 1998 the Copyright Term Extension Act further extended copyright protection to the duration of the author's life plus 70 years for general copyrights and to 95 years from date of publication or 120 years from date of creation, whichever comes first, for works made for hire. Works copyrighted before 1978 have a duration of protection that depends on a variety of factors.

Transfer of copyright

Section 204 of the Act governs the transfer of ownership of copyrights. The section requires a copyright holder to sign a written instrument of conveyance that expressly transfers ownership of the copyright to the intended recipient for a transfer to be effective.[11] Prior case law on this issue was conflicting, with some cases espousing a rule similar to section 204 and others reaching a quite different conclusion. In the 1942 New York case Pushman v. New York Graphic Society,[12] for example, the court held that although a copyright in a work is distinct from a property right in a copy of the work, where the only existing copy of the work is transferred, the copyright is transferred along with the copy, unless expressly withheld by the author. Section 202 of the 1976 Act retains the property right/copyright distinction, but section 204 eliminates the inconsistent common law by assuming that the copyright is withheld by the author unless it is expressly transferred.

Registration and deposit

According to section 408 of the Act, registration of a work with the Copyright Office is not a prerequisite for copyright protection.[13] The Act does, however, allow for registration, and gives the Copyright Office the power to promulgate the necessary forms. Aside from Copyright Office paperwork, the Act requires only that one copy, or two copies if the work has been published, be deposited with the Office to accomplish registration. Though registration is not required for copyright protection to attach to a work, section 411 of the Act does require registration before a copyright infringement action by the creator of the work can proceed.[14] Even if registration is denied, however, an infringement action can continue if the creator of the work joins the Copyright Office as a defendant, requiring the court to determine the copyrightability of the work before addressing the issue of infringement.

Termination rights

The Act also codified the ability for writers and other artists that license their work to others to act on termination rights 35 years after the publication of the work.[15] This was intended to allow these people to renegotiate licenses at the later period if the value of the original work was not apparent at the time or creation. This protection only applies to works made after 1978, and does not apply to works made for hire. The law requires the creator to issue notice of termination at least 2 years prior to the 35-year date giving the rights holder time to prepare.[16]

Impact on innovation

One of the functions of the Copyright Royalty Judges defined by the Copyright Act is to "minimize any disruptive impact on the structure of the industries involved and on generally prevailing industry practices". Critics of the law have questioned this aspect of it, as it discourages innovation and perpetuates older businesses.[17]

Legacy

Impact on internet radio

Streaming music on a portable device is mainstream today, but digital radio and music streaming websites such as Pandora are fighting an uphill battle when it comes to copyright protection. 17 USC 801(b)(1)(D) of the Copyright Act states that Copyright Royalty Judges should "minimize any disruptive impact on the structure of the industries involved and on generally prevailing industry practices".[17] "Much of the initial drafting of the '76 Act was by the Copyright Office, which chaired a series of meetings with prominent industry copyright lawyers throughout the 1960s".[18] Some believe that Section 106 was designed with the intent to maximize litigation to the benefit of the legal industry, and gives too much power and protection to the copyright holder while weakening fair use.

Critics of the Copyright Act say that Pandora will never be profitable if something does not change because "services like Pandora already pay over 60 percent of their revenue in licensing fees while others pay far less for delivering the same service. As a result, services like Pandora have been unable to see profitability and sustainability is already in question." An increase in subscription fees would likely be an end to Pandora's business.[19]

Impacts of termination rights

The termination right clause only started taking effect in 2013, with notably Victor Willis terminating rights on the songs he had written for The Village People. A lawsuit resulted from this action Scorpio Music, et al. v. Willis in 2012 (after Willis had filed notice of termination to Scorpio Music, the music distributor, and which the court upheld Willis' termination rights. Subsequently, other songwriters began seeking termination rights.[16] This has also become an issue in the film industry, as the rights to many iconic 1980s film franchises are being terminated by their original writers, such as by the family of Roderick Thorp whose novel Nothing Lasts Forever was adapted into Die Hard.[20]

See also

- United States copyright law

- Digital Millennium Copyright Act

- Copyright Term Extension Act

- Proposed legislation

References

- Decisions of the United States Courts Involving Copyright. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1985. pp. 311–.

- See House report number 94-1476.

- "Barbara A. Ringer '49". Archived from the original on 2014-06-02. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- "Righting Copyright", Time, November 1, 1976, p. 92.

- 17 U.S.C. 102

- Demers, Joanna (2006). Steal This Music: How Intellectual Property Law Affects Musical Creativity. The University of Georgia Press. p. 22.

- 17 U.S.C. 106

- 17 U.S.C. 107

- – via Wikisource.

- "U.S. Copyright Act of 1976" (PDF). United States House of Representatives. p. 90 STAT. 2572.

- 17 U.S.C. 204

- Pushman v. New York Graphic Society, 39 N.E.2d 249 (N.Y. 1942)

- 17 U.S.C. 408

- 17 U.S.C. 411

- 17 U.S.C. 203

- Caplan, Brian (August 2012). "Navigating US Copyright Termination Rights". WIPO Magazine. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- Masnick, Mike (17 September 2012). "The Copyright Act Explicitly Says Disruptive Innovation Should Be Blocked". techdirt.com. Mike Masnick. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- Weber, Peter (10 July 2014). "Death to Pandora? A guide to the looming music copyright war". Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- Versace, Chris (23 June 2014). "The Future of Streaming Music Rest with Congress". Archived from the original on 27 November 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- Gardner, Eriq (October 2, 2019). "Real-Life 'Terminator': Major Studios Face Sweeping Loss of Iconic '80s Film Franchise Rights". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- US Copyright Office, Title 17

- Cornell Law School, on Copyright

- World wide school.org

- New York Law School Law Review, The Complete Guide to the New Copyright Law, Lorenz Press Inc., 1977, ISBN 0-89328-013-5

- Reproduction of Copyrighted Works by Educators and Librarians (Circular 21). United States Copyright Office, United States Library of Congress.(This circular cites and describes the key legislative history documents for the law, and briefly outlines the guidance that the legislative history provides.)