Corporate law in Vietnam

Corporate law in Vietnam[1] was originally based on the French commercial law system. However, since Vietnam's independence in 1945, it has largely been influenced by the ruling Communist Party. Currently, the main sources of corporate law are the Law on Enterprises,[2] the Law on Securities[3] and the Law on Investment.[4]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Corporate law |

|---|

|

|

History of corporate law and sources of law in Vietnam

The post-independence period (1945–1986)

Corporate law in Vietnam is largely influenced by French laws due to its colonial past. After the 1954 Geneva Conference, Vietnam separated into two zones: the North and the South. In 1980, after the North took control of the South, the country adopted a centrally-planned economy, with officials discouraging private commerce.[5]

Doi Moi (post-1986)

In 1986, the government initiated economic reforms (Doi Moi) to the corporate sector to reinvigorate the ailing economy. These policies aimed to reverse most of policies that led to economic crises in the 1970s and 1980s following the Vietnam War. Development of the private sector was encouraged and the economy was liberalized in hopes of increasing the potential for economic development. In 1987, the Law on Foreign Investment was passed, allowing foreign investors into the country.[6]

In 1990, the Law on Private Enterprises and Companies Law were introduced to boost economic development. They were subsequently superseded by the Law on Enterprises (LOE) in 1999, which introduced Partnerships in addition to Limited Liability Companies and Shareholding Companies. Within three years of implementing the LOE, over 70,000 enterprises were registered as compared to just over 40,000 for the previous nine years.[7] Law on Investment (replacing Law on Foreign Investment) and a new LOE were enacted in 2005.[8] These statutes are expected to further strengthen Vietnam's economy and its potential for international economic integration.

Main sources of law in Vietnam

The Constitution - Mainly seen as the ultimate Party policy documents. [9] 4 different versions (1946, 1959, 1980, 1992)

Legislation - Originated from civil law passed down from the French.[10]

Forms of business enterprise

The LOE governs business enterprises in Vietnam. Enterprises in all economic sectors have to satisfy the stipulated conditions accounted for in Article 7(2). There are 4 forms of business enterprises.

Limited liability company (LLC)

An LLC is established by members' capital contribution to the company. As a LLC is a legal entity separate from the owners, the owner(s)'s liability for the firm's debts and obligations is limited to his capital contribution.[11]

LLCs exist in two forms - one-member LLC, or multi-member LLC. The former is owned by an organisation/individual,[12] while the latter allows for two to fifty members.[13]

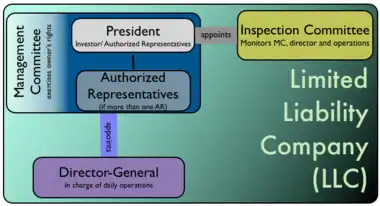

The management structure consists of a Members' Council (MC), Chairperson of the MC and Director. Where there are more than 11 members in LLC, an Inspection Committee (IC) must also be established.[14]

Shareholding Company (SC)

An SC is an entity with at least three shareholders,[15] where ownership of the firm depends on the number of shares they hold. It is the only form of enterprise that can issue securities to raise capital.

Shareholders' liability is limited to their capital contribution;[16] however, shareholders can be personally liable where the company is substantially undercapitalised on formation.

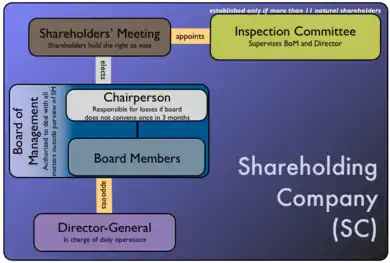

The management structure consists of a shareholders' meeting (SM), a board of management (BOM), a director and an IC.[17]

Partnership

A partnership comprises at least two co-owners jointly conducting business under one common name,[18] with at least one co-owner being an individual. In a partnership, there can be both limited[19] and unlimited liability[20] partners.

The Partners' Council, consisting of all partners, is the highest body in the partnership with the right to resolve all business affairs, such as the admission of new partners.[21]

Private enterprises

A private enterprise is a firm owned by an individual, who is its legal representative[22] The owner has total discretion in making business decisions,[23] and is liable for its operations to the extent of all his assets.[24] Each individual can only establish one private enterprise.[25]

Rules concerning ownership of businesses

The government has rules to restrict certain lines of businesses,[26] and will periodically review business conditions and proceed with any changes accordingly.

The rights and obligations of business enterprises are provided for in Articles 8–10; but might differ slightly should the enterprise offer public services or products.

Limited liability company (LLC)

Owners in LLCs have to contribute capital in full and on time. In one-member LLCs, the owner will be responsible for debts and other property obligations if he fails to do so.[27] Meanwhile, in multi-member LLCs, members are to contribute capital in the type of asset, and any change is subject to the consent of other members.[28]

Owners in LLCs can assign a share of their capital contribution except where prohibited.[29] In one-member LLCs, this is the only way for the owner to withdraw capital.

Shareholding Company (SC)

The government provides specific provisions on the forms of offering securities to the public.[30] In offering securities, SCs are subject to conditions laid out in the Securities Law, such as the requirement for a paid-up charter capital at the time of offering of at least VND 10 billion in book value.[31]

Founding shareholders can assign their registered ordinary shares to each other if they hold 20% of ordinary shares for 3 years from the date of the Business Registration Certificate. Approval at the SM will allow a non-founding shareholder to purchase registered ordinary shares from a founding shareholder.

Partnerships

If an unlimited-liability partner fails to contribute capital accordingly, other partners may be held liable to compensate the partnership for the damage. However, where the limited liability partner fails to contribute capital accordingly, the unpaid amount will become a debt owed by that partner to the partnership.

An unlimited liability partner can transfer his share of capital in the partnership to another person only with the consent of the other unlimited liability partners.

Private enterprises

The owner must register his investment capital in the firm, and record changes in the investment capital in the accounts.

Rules concerning corporate governance

Ownership

The ownership powers of the enterprises are vested in the MC/Chairman for LLCs[32][33] and in the SM and BOM for SCs.[34][35] They are the highest decision making bodies for each enterprise and are tasked with the passing of resolutions, amending the Company Charter and setting out the general direction of the Company, etc.[36][37][38] A resolution can only be passed with a minimum percentage approval.[39][40] Such a rule is put in place to ensure the interests of all shareholders are protected.

Executive

The Director, appointed by the ownership institutions of the enterprise, has Executive powers and oversees the day-to-day running of the Company for SCs[41] and LLCs.[42][43] He is legally responsible for the implementation of delegated rights and obligations. Directors of LLCs cannot be affiliated to any member of the MC,[44] ensuring the separation of powers between the company's ownership and management.

However, for SCs, the LOE permits persons to take up dual roles as Director and chairman of the BOM.[45] One survey found that 75% of chairmen of a BOM were also the Directors of their company. Furthermore, other members of the BOM are often majority shareholders and managers of the company. This highlights an indefinite differentiation between ownership and management.

Inspection

The LOE prescribes the formation of a mandatory IC to monitor and check the ownership and executive powers.[46][47] Members of the IC must minimally possess professional qualifications or accounting/auditing work experience,[48] and cannot be related to members of the ownership or executive bodies.[48] This ensures impartiality and prevents conflict of interests. However, in SCs, while members of the IC cannot hold any managerial positions in the company, they are allowed to own company shares or be a general employee of the Company.[49]

Ownership Representatives

Where the MC/Chairman of the LLC fails to convene a requested meeting within 15 days of the request, he must bear personal liability for any damage that may result to the company.[50]

Executive

The LOE prescribes that the Director of a LLC may be sued by shareholders should he fail to perform his obligations and duties.[51] In contrast, in a SC, there are no such provisions to grant the shareholders power to bring an action against Directors who do not perform their duties. While the law lays out the fiduciary duties of the Directors, it does not provide a way to enforce these duties. This has led to the criticism that the interests of shareholders of SCs are not adequately protected.[52]

Inspectors

The IC is legally responsible for the implementation of its rights and duties.[46] The LOE however does not specify the circumstances under which the IC will be deemed to have neglected its rights and duties and hence be legally liable.

Restrictions on transactions with owners/shareholders

The LOE prescribes certain regulations to control and approve large related-party transactions. For SCs, if a loan agreement/contract is valued at at least 50% of the company's total assets, it is subject to approval by the BOM.[53]

All related-party transactions must be approved by the shareholders.[53] 'Related-party' include managers of the enterprise or family members of shareholders,[54] and related-party transactions are business arrangements between two parties with prior relationships.

Management personnel have to disclose details of their and their related parties' ownership interests in other enterprises; the latter applies where the related-party holds more than 35% of charter capital.[54] These measures ensure that personal interests do not override the company's interests. In addition, shareholders or directors related to the transaction cannot vote on the deal.[55]

The LOE, however, does not provide for an external checking mechanism for related-party transactions. The BOM has the sole and unfettered right to give approval to related-party transactions, and this lack of an extra checking mechanism has resulted in a lack of investor protection in Vietnam.[Note 1]

Foreign investment

Both foreign and domestic investments are similarly treated under the LOI. Foreign investors and expatriates working for foreign-invested businesses or business co-operation contract can remit investment capital, profits and other assets, and their income abroad respectively.[57] There are four types of foreign investment in Vietnam:[58]

- 100% Foreign Owned Enterprise (FOE);

- Joint-Venture Enterprise (JV);

- Business Co-operation Contract (BCC); and

- Building–Operation–Transfer/Building– Transfer–Operation/Building–Transfer. (BOT/BTO/BT)

Foreign owned enterprise

Foreign investors may establish economic organizations or LLCs in the form of 100% capital of foreign investors.[59]

Joint venture

Foreign investors may enter a joint venture where there is at least one foreign and one domestic investor.[60] The operational duration of a Foreign Invested Project cannot exceed 50 years; where the Government thinks it necessary to continue, it cannot exceed 70 years.[61] FOEs are recommended over joint ventures and they can be formed quickly through application of investment licenses. Joint ventures face problems such as corruption and the lack of control over the business.[62]

Business cooperation contract

Foreign investors may invest in contractual agreements with Vietnamese partners to cooperate on specific business activities. This form of investment does not constitute a new legal entity and the investors have unlimited liability for BCC's debts.[63]

BOT/ BTO/ BT

A foreign investor can sign such a contract with a State body to implement projects for expansion and modernization of infrastructure projects in the sectors stipulated by the Government.[64][65]

Analysis and assessment of current rules

Flexibility in choosing corporate governance structures

Although Vietnam's corporate law adopted Anglo-American legal principles, common law jurisdictions like the US grant businesses greater flexibility in choosing corporate governance structures. The LOE, however, imposes mandatory internal governance structures.[66] This has been criticised for failing to give companies the latitude to adapt their corporate governance structures to suit their needs.[67] Anglo-American law allows directors to delegate their powers to a sub-committee or another person.[68] Meanwhile, in Vietnam, subcommittees can be established to assist the BOM, but the latter cannot delegate its powers to the former. The imposition of mandatory corporate governance structures without delegation of powers leads to less flexibility and efficiency.[69]

Separation of supervisory and management bodies

Internal governance structures are important in supervising the company managers. In US, the supervisory body is often subsumed within the single-tiered board of directors, whereas in Vietnam, the IC is an independent body. Through separation of supervisory and management functions, the Vietnamese corporate law model, at least theoretically, ensures that the BOM is held to a greater degree of accountability by an independent checking mechanism. However, there is no hierarchy for the Vietnamese IC and BOM. This contrasts with the German two-tiered board model for SCs, with an Aufsichtsrat (supervisory board) which is hierarchically superior to the Vorstand (management board). Because the IC is not recognised as a superior institution, it has limited authority over the BOM. In practice, many supervisors are low level employees within the company. Although institutionally independent, the members of the IC are, in reality, dependent on their employers for their livelihoods, and therefore serve as a weak check against mismanagement by the BOM or Director.

Vesting of executive powers

In Vietnam, executive powers are vested solely in the Director while in Germany, executive powers are shared equally amongst members of the Vorstand. This encourages consensus decision-making in German companies as responsibility is shared amongst all members of the Vorstand.[70] This can be further contrasted with Japan, where the corporate law does not designate any positions for corporate officers (the Vietnamese equivalent of Director) and executive powers are largely retained within the Board of Directors (the Vietnamese equivalent of BOM).[71]

Understanding corporate governance and role of management structures

Corporate governance in Vietnam is seen more as a management framework rather than a system for accountability and protecting minority shareholders. In particular, the LOE does not clearly mandate the separation of ownership and management. Separation of ownership and management promotes accountability by allowing managers to be objectively appraised. On the other hand, owners who serve as managers will be more likely to pursue their own interests, possibly at the expense of the interests of minority shareholders.

State-owned enterprises

Following the introduction of LOE, SOEs were converted to single-organisation-owned LLCs.[72] However, the state retains many powers and is directly involved in management decision-making. Government officials are thus selected to run companies for political reasons. Their lack of business expertise and profit motive has led to inefficiency and mismanagement of large state-owned enterprises.[73] Furthermore, since only up to three supervisors can be appointed, there is limited monitoring on the company managers. In 2010, the state-owned shipbuilding firm Vinashin ended in bankruptcy, following mismanagement and false reporting of financial statements.[74] This reflects the inadequate monitoring and auditing mechanisms for SOEs.

Investor protection

The LOE is increasingly recognizing the interests of minority shareholders by introducing new avenues for them to hold the management accountable.[Note 2] Nonetheless, with stringent prerequisites including higher shareholding requirements and the need to show evidence before minority shareholders can call for a shareholders' meeting, investor protection in Vietnam is still limited compared to other jurisdictions.[Note 3] Other shortcomings of the LOE include limited opportunities for shareholders to request a meeting, no imposition of legal responsibilities on board members who approve unfair transactions, no shareholders' rights to sue those in the corporate governance structure (for SCs), and a shortage of provisions to require disclosure obligations and directors to avoid insolvent trading.

See also

- List of company registers

Notes

- In a 2006 World Bank research, Vietnam tallied a score of 0 in the extent of director liability index, a stark contrast to the average score of 4.4 attained for East Asia and Pacific economies.[56]

- These new measures includes basic rights of shareholders such as attending the General Shareholders' Meeting, voting on the basis of one share one vote, selecting senior managers and supervisors and having priority in making additional capital contributions, among others.

- These other jurisdictions include China, Spain, Ireland, Italy, Australia, Germany and New Zealand.

References

- "Commercial Law - Vietnam". Asiapedia. Dezan Shira and Associates.

- Law on Enterprises

- Law on Securities

- Law on Investment

- Library of Congress, F. R. (1987). Vietnam Country Study. Retrieved August, 2011, from http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/vntoc.html

- Asian Development Bank. (2011). Economy of Vietnam - An Overview. Retrieved August, 2011, from 44th Annual Meeting, Board of Governors, Asian Development Bank: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-03-26. Retrieved 2011-08-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bai, X. H. (2006). Vietnamese Company Law: The Development and Corporate Governance Issues. Bond Law Review , 25.

- Bai, X. H., & Walker, G. (2005). Transitional Adjustment Problems in Contemporary Vietnamese Company Law. Journal of International Banking Law and Regulation , 567-576.

- Nicholson, P. (2007). Borrowing Court Systems - The Experience of Socialist Vietnam. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, at 47

- Nicholson, P. (2007). Borrowing Court Systems - The Experience of Socialist Vietnam. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Appendix 6

- Articles 38 and 63, Law of Enterprises 2005.

- Article 63, Law of Enterprises 2005.

- Article 38, Law of Enterprises 2005.

- Article 46, Law on Enterprises 2005.

- Article 77(1)(b), Law on Enterprises 2005.

- Article 77(1)(c), Law on Enterprises 2005.

- Article 95, Law on Enterprises 2005.

- Article 130(1)(a), Law on Enterprises 2005.

- Article 130(1)(c), Law on Enterprises 2005.

- Article 130(1)(b), Law on Enterprises 2005.

- Article 135, Law on Enterprises 2005.

- Article 143(4), Law on Enterprises 2005.

- Article 143(1), Law on Enterprises 2005.

- Article 141(1), Law on Enterprises 2005.

- Article 141(3), Law on Enterprises 2005.

- Article 7, Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 65, Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 39(1) Law of Enterprises 2005

- Such prohibitions are laid down in Article 45(6).

- Article 11, Securities Law 2006

- Article 12, Securities Law 2006

- Article 47(1), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 68(1), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 96(1), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 108(1), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 47(2), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 96(2), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 104(2), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 52(2), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 68(6), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 116 (2), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 55(1), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 70(1), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 70(3), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 111 (1), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 71, Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 121, Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 71(4), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 122(2), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 50(5), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 41(1g), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Le Minh, Toan and Walker, Gordon (2008) "Corporate Governance of Listed Companies in Vietnam," Bond Law Review: Vol. 20: Iss.2, Article 6.

- Article 120(2), Law on Enterprises 2005

- Article 4(17), Law on Enterprises 2005.

- Article 120 Section 3, Law on Enterprises 2005

- Le Minh, Toan and Walker, Gordon (2008) "Corporate Governance of Listed Companies in Vietnam," Bond Law Review: Vol. 20: Iss.2, Article 6.

- Vietnam - A Guide for Business and Investment, 2008, PriceWaterHouseCoopers

- Article 21, Law on Investment 2005

- Article 21 (1), Law on Investment 2005

- Article 21 (2), Law on Investment 2005

- Article 52, Law on Investment 2005

- Vietnam –Open for Business?, http://www.business-in-asia.com/vn_industrial.html Archived 2011-08-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Article 21 (3), Law on Investment 2005

- Article 21 (4), Law on Investment 2005

- Article 23 (2), Law on Investment 2005

- Katharina Pistor et al, 'The Evolution of Corporate Law: A Cross‐Country Comparison' (2003) 23(4) University of Pennsylvania, Journal of International Economic Law 791, 19,

- Xuan Hai, Bui, and Nunoi, Chihiro, Corporate Governance in Vietnam: A System in Transition, Hitotsubashi Journal of Commerce and Management 42 (2008), pp.45-65.

- See, e.g. ss 198C(1), 198(1) of the Corporation Act 2001 (C th) of Australia.

- See, e.g. American Law Institute, Principles of Corporate Governance: Analysis and Recommendations (Vol. 1, 1994) s.305, Part III‐A (ss 3A.01‐3A.05).

- Jonathan P. Charkham (1994). Keeping Good Company: A Study of Corporate Governance in Five Countries. Oxford University Press. pp. 14–21

- http://finance.wharton.upenn.edu/~allenf/download/Vita/Japan-Corporate-Governance.pdf

- Decree No. 95/2006/ND-CP of Government dated Sept. 8, 2006

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-08-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2011-08-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)