Corpus Coranicum

Corpus Coranicum is a research project of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities towards a critical edition of the Quran.

Begun in 2007, the initial three-year database project is led by Semitic and Arabic studies Prof. Angelika Neuwirth at the Free University of Berlin. The project is currently funded till 2025, but could well take longer to complete.[1]

Outside of Corpus Coranicum, critical work is scarce. Abdelmajid Charfi printed a critical historical edition in 2018,[2] and Qur'an Gateway provides a commercial database of textual variants of the Quran.[3]

Goals and methodology

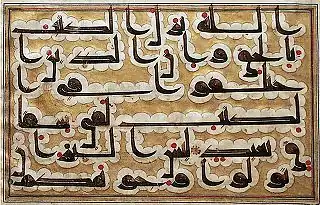

The project will document the Quran in its handwritten form and oral tradition, and include an extensive commentary interpreting the text in the context of its historical development.[4]

Much of the Corpus Coranicum source material consists of photographs of ancient Quran manuscripts collected before World War II by Gotthelf Bergsträsser and Otto Pretzl. After the British RAF on 24 April 1944 bombarded the building where they were housed, Arabic studies scholar Anton Spitaler claimed the photograph collection had been destroyed. Towards the end of his life, however, he confessed to Neuwirth that he had hidden the photos for almost half a century, and Neuwirth assumed responsibility for the archive.[1]

The project's research director, Michael Marx, told Der Spiegel that the Quran did not arise in a vacuum, as for the sake of simplicity some western researchers had supposed. The Arabian peninsula in the 7th century was exposed to the great Byzantine and Persian Empires as well as the ideas of Gnosticism, early Christianity, the ideals of ancient Arabic poetry and the ideas of rabbinic Judaism. Only in light of this world of ideas, Marx added, "can the innovations of the Quran be clearly seen,"[5] and while parallels exist with non-Quranic texts, "it is not a copy-and-paste job."[6]

One goal is to distinguish between the manuscript and orally transmitted readings of the Quran, and to document both traditions online. Secondly, a database of international texts (including pre-Quranic and Judeo-Christian texts)[7] will place the development of the Quran in the context of its spatial and temporal environment and foster better understanding among Westerners. The third part of the project is to create a commentary focusing not only on individual problems but also including form-critical analyses. The commentary is constructed discursively, taking note of earlier opinions and research on the Quran.

The ultimate critical edition will compare surviving pre-Uthmanic variants, variants between the Qira'at (the roughly two dozen versions of Uthman's Quran), manuscript variants within individual Qira'at, and the variants chosen by the 1924 Cairo edition of the Hafs Qira'at. These variants include consonantal mutations, and encompass the addition and removal of whole words.[8]

Student Humanities Laboratory

In April 2008, Yvonne Pauly wrote that the academy's Student Humanities Laboratory had created a teaching unit on Quranic research, declaring: "While the Quran is religiously, culturally and politically influential, it is also controversial, though the heated debate surrounding the text often stands in contrast to an actual knowledge of its contents."[9] Through the example of one of the shorter suras, teenagers would explore the text through the tools of modern philology while experiencing it orally and through calligraphy as well, with the aim of increasing the students' curiosity and scientific interest in the humanities during their transition to university.[9]

Controversy

In 2007 journalist-publisher Frank Schirrmacher wrote an article for the Frankfurt Book Fair suggesting that the Academy's preparation of a historically critical Quran edition had been motivated by Pope Benedict XVI's ill-received Regensburg lecture of 2006 and predicting that the Corpus Coranicum would spark similar outrage among Muslims, comparing it to the punishment of Prometheus for bringing fire to mankind. He was enthusiastic that the fruits of their research might even "overthrow rulers and topple kingdoms".[10] Marx promptly called the Al-Jazeera television network to deny any attempt to attack Islamic tenets.[1]

Angelika Neuwirth demurred: "It would be quite wrong to claim triumphantly that we had found the key to the Quran and that Muslims for 14 long centuries had not." Instead, she and her colleagues have chosen a nonconfrontational approach that includes regular dialogue with the Islamic world[5] and aims "to give the Quran the same attention as the Bible."[1]

Michael Marx, Neuwirth and Nicolai Sinai spiritedly defended the project, writing that negative reaction to the papal speech should not be equated with Islamic hostility towards a historical-textual or philological approach to the Quran.[11] On the contrary, they asserted, classical commentaries within the Islamic tradition are concerned with the "occasions of revelation" (asbâb an-nuzûl) of particular suras, while Islamic literature discussing alternative interpretations of the Qur'an — "a sort of textual criticism avant la lettre" — can fill library shelves.

In discussions with Iranian, Arab and Turkish scholars in Tehran, Qom, Damascus, Fez, Rabat, Cairo and Istanbul Marx, Neuwirth and Sinai had contended that even if one considered the Quran as the literal words of God, a contextual reading as a legitimate subject of historical inquiry could create a climate of healthy inquiry and debate among Islamic and non-Islamic researchers alike. The trio's letter also pointed out that the Corpus Coranicum project was in any case not directed to Islamic fundamentalists, but to Germans and other Europeans.[11]

References

- Andrew Higgins and Almut Schoenfeld, "The Lost Archive: Missing for a half century, a cache of photos spurs sensitive research on Islam's holy text", Wall Street Journal, 12 January 2008. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- "Critical Koran edition "Al-Mushaf wa Qiraʹatuh"". Qantara.de - Dialogue with the Islamic World. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "About". Qurʾan Gateway. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Corpus Coranicum Archived 2011-02-26 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 2010-02-07.

- Yassin Musharbash, "Die Klimaforscher des Korans" ("Climate researchers of the Quran") in Der Spiegel, 1 November 2007. Retrieved 2010-002-07.

- Interview with Michael Marx, Muslimische Stimmen (German, 440 kB) 14 May 2008. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- "Corpus Coranicum prospectus". Retrieved 2010-02-05.

- "Quran Manuscripts, Copyist Errors, and Viable Variants". Is the Quran the Word of God?. 21 August 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Den Koran verstehen lernen", press release, 2 April 2008. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- Frank Schirrmacher, "Bücher können Berge versetzen" ("Books can move mountains"), Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Bücher, 10 October 2007. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- Michael Marx, Angelika Neuwirth and Nicolai Sinai, "Koran, aber in Kontext — Eine Replik" ("The Quran, but in context — a reply"), Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 6 November 2007.