Fez, Morocco

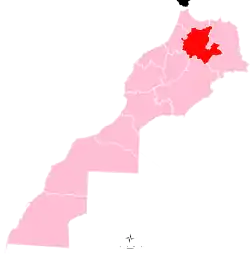

Fez or Fes (/fɛz/; Arabic: فاس, romanized: fās, Berber languages: ⴼⴰⵙ, romanized: fas, French: Fès) is a city in northern inland Morocco and the capital of the Fès-Meknès administrative region. It is the second largest city in Morocco after Casablanca,[4] with a population of 1.22 million (2020). Located to the northeast of the Atlas Mountains, Fez is situated at a crossroad connecting the important cities of different regions; 206 km (128 mi) from Tangier to the northwest, 246 km (153 mi) from Casablanca, 189 km (117 mi) from Rabat to the west, and 387 km (240 mi) from Marrakesh to the southwest which leads to the Trans-Saharan trade route. It is surrounded by hills and the old city is centered around the Fez River (Oued Fes) flowing from west to east.

Fez

| |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp)  _(3211614119).jpg.webp) Clockwise from top: Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque/University, Avenue Hassan II in the Ville Nouvelle ("new city"), gates of the Royal Palace, the Zawiya of Moulay Idris II on the skyline of Fes el-Bali, Chouara Tannery, and Bab Bou Jeloud gate | |

Fez Location of Fez within Morocco  Fez Fez (Africa) | |

| Coordinates: 34°02′36″N 05°00′12″W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Fès-Meknès |

| Founded | 789 |

| Founded by | Idrisid dynasty |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Idriss Azami Al Idrissi |

| • Governor | Said Zniber |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 320 km2 (120 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 410 m (1,350 ft) |

| Population (2014)[2] | |

| • City | 1,150,131 |

| • Rank | 2nd in Morocco |

| • Demonym | Fassi |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| Area code(s) | +212 (55) |

| Website | www.fes-city.com |

| Official name | Medina of Fez |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv |

| Designated | 1981 |

| Reference no. | [3] |

| State Party | Morocco |

| Region | Arab States |

Fez was founded under Idrisid rule during the 8th-9th centuries CE. It initially consisted of two autonomous and competing settlements. Successive waves of mainly Arab immigrants from Ifriqiya (Tunisia) and al-Andalus (Spain/Portugal) in the early 9th century gave the nascent city its Arab character. After the downfall of the Idrisid dynasty, other empires came and went until the 11th century when the Almoravid Sultan Yusuf ibn Tashfin united the two settlements into what is today's Fes el-Bali quarter. Under Almoravid rule, the city gained a reputation for religious scholarship and mercantile activity. Fez reached its zenith in the Marinid era (13th-15th centuries), regaining its status as political capital. Numerous new madrasas and mosques were constructed, many of which survive today, while other structures were restored. These buildings are counted among the hallmarks of Moorish and Moroccan architectural styles. In 1276 the Marinid sultan Abu Yusuf Yaqub also founded the royal administrative district of Fes el-Jdid, where the royal palace is still located today, to which extensive gardens were later added. During this period the Jewish population of the city grew and the Mellah (Jewish quarter) was formed on the south side of this new district. After the overthrow of the Marinid dynasty, Fez largely declined and subsequently competed with Marrakesh for political and cultural influence, but remained as the capital under the Wattasids and in modern times up until 1912.

Today, the city consists of two old medina quarters, Fes el-Bali and Fes el-Jdid, and the much larger modern urban Ville Nouvelle area founded during the French colonial era. The medina of Fez is listed as a World Heritage Site and is believed to be one of the world's largest urban pedestrian zones (car-free areas).[5] It has the University of Al Quaraouiyine which was founded in 859 and is considered by some to be the oldest continuously functioning institute of higher education in the world. It also has Chouara Tannery from the 11th century, one of the oldest tanneries in the world. The city has been called the "Mecca of the West" and the "Athens of Africa," a nickname it shares with Cyrene in Libya.[6]

Etymology

Fez or Fas was derived from the Arabic word فأس Faʾs which means pickaxe, which legends say Idris I of Morocco used when he created the lines of the city. One noticeable thing was that the pickaxe was made from silver and gold.[7][8]

During the rule of the Idrisid dynasty, Fez consisted of two cities: Fas, founded by Idris I,[9] and al-ʿĀliyá, founded by his son, Idris II. During Idrisid rule the capital city was known as al-ʿĀliyá, with the name Fas being reserved for the separate site on the other side of the river; no Idrisid coins have been found with the name Fez, only al-ʿĀliyá and al-ʿĀliyá Madinat Idris. It is not known whether the name al-ʿĀliyá ever referred to both urban areas. It wasn't until 1070 that the two agglomerations were united and the name Fas was used for the combined site.[10]

History

Foundation and the Idrisids

The city was first founded in 789 as Madinat Fas on the southeast bank of the Jawhar River (now known as the Fez River) by Idris I, founder of the Idrisid dynasty. His son, Idris II,[11] built a settlement called Al-'Aliya on the opposing river bank in 809 and moved his capital here from Walili (Volubilis).[12]:35[13]:35[14]:83 These settlements (Madinat Fas and Al-'Aliya) would soon develop into two walled and largely autonomous sites, often in conflict with one another. The early population was composed mostly of Berbers, along with hundreds of Arab warriors from Kairouan who made up Idris II's entourage.[12][14]

Arab emigration to Fez increased afterwards, including Andalusi families of mixed Arab and Iberian descent[15] who were expelled from Córdoba in 817–818 after a rebellion against the Al-Hakam I[12]:46[16] as well as Arab families banned from Kairouan (modern Tunisia) after another rebellion in 824. The Andalusians mainly settled in Madinat Fas, while the Tunisians found their home in Al-'Aliya. These two waves of immigrants gave the city its Arabic character and would subsequently give their name to the districts of 'Adwat Al-Andalus and 'Adwat al-Qarawiyyin.[17]:51 With the influx of Arabic-speaking Andalusians and Tunisians, the majority of the population was Arab, but rural Berbers from the surrounding countryside settled there throughout this early period, mainly in Madinat Fas (the Andalusian quarter) and later in Fes Jdid during the Marinid period.[18] The city also had a strong Jewish community, probably consisting of Zenata Berbers who had previously converted to Judaism, as well as a small remaining Christian population for a time. The Jews were especially concentrated in a northeastern district of Al-'Aliya known as Funduq el-Yihoudi (near the later Bab Guissa).[19]:42–44

Each city had its great mosque, its markets, and currency. The area was blessed with water flowing everywhere. Water was diverted from the Oued Fes along channels into homes. The streets were paved and, according to the tenth-century geographer, Ibn Hawqal, water was flushed into the suqs every summer night to clean the ground. The water was also transported to public baths and 300 mills. The city grew quickly and by the late 900s, it had about 100,000 inhabitants.[20]

Upon the death of Idris II in 828, the dynasty's territory was divided among his sons. The eldest, Muhammad, received Fez, but some of his brothers attempted to break away from his leadership, resulting in an internecine conflict. Although the Idrisid realm was eventually reunified and enjoyed a period of peace under Ali ibn Muhammad and Yahya ibn Muhammad, it fell into decline again in the late 9th century.[21]

According to one of the major early sources on this period, the Rawd al-Qirtas by Ibn Abi Zar, in this period the Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque was founded in 859 by Fatima al-Fihri, the daughter of a wealthy merchant. Her sister, Mariam, is likewise reputed to have founded the Al-Andalusiyyin Mosque the same year.[22][19] Comparatively little is known about Idrisid Fez, owing to the lack of comprehensive historical narratives and that little has survived of the architecture and infrastructure of early Fez. The sources that mention Idrisid Fez, describe a rather rural one, not having the cultural sophistication of the important cities of Al-Andalus and Ifriqiya.

In the 10th century, the city was contested by the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba and the Fatimid Caliphate of Ifriqiya (Tunisia), who ruled the city through a host of Zenata clients.[14][17][21] The Fatimids took the city in 927 and expelled the Idrisids definitively, after which their Miknasa (one of the Zenata tribes) were installed there. The city, along with much of northern Morocco, continued to change hands between the proxies of Córdoba and the proxies of the Fatimids for many decades. Following another successful but ephemeral Fatimid takeover of Morocco in 979 by Buluggin ibn Ziri, the forces of Al-Mansur of Cordoba managed to retake the region again, expelling the Fatimids permanently.[21] From 980 (or from 986[23][12]), Fez was ruled by a Zenata dynasty from the Maghrawa tribe, who were allies of the Caliphate of Córdoba. They maintained this control even after the Caliphate's collapse in the early 11th century and until the arrival of the Almoravids.[13]:16[23]:91[14][23]

Under Zenata control Fez continued to grow even though conflicts between its two settlements, Madinat Fas and Al-'Aliya, continued to flare up during periods of political rivalry. Ziri ibn Atiyya, the first ruler of the new dynasty, had a troubled reign.[12] In 1033, under the leader Tamim, several thousand Jews were killed in the Fez Massacre. However, Ibn Atiyya's descendant Dunas ibn Hamama, ruling between 1037 and 1049, was responsible for many important infrastructural works necessary to accommodate Fez's growing population.[24] He developed much of Fez's water distribution infrastructure, which has largely survived up to the present day.[24][25] Other structures built in his time included hammams (bathhouses), mosques, and the first bridges over the Oued Bou Khareb (mostly rebuilt in later eras).[12][24][26][27][28] Thus, the two cities became increasingly integrated into each other: the open space between the two was increasingly filled up by new houses and up to six bridges across the river allowed for easier traffic between the two shores.[27]:36 A decade after Dunas, however, between 1059 and 1061, the two opposing settlements of the city were ruled separately by two rival Zenata emirs: Al-'Aliya was controlled by an emir named Al-Guissa and Madinat Fas was controlled by Al-Foutouh. Both brothers fortified their respective shores, and their names have been preserved in two of the city's gates to this day: Bab Guissa in the north and Bab Ftouh in the south.[12][24]

Golden age: under the Almoravids, Almohads, and Marinids

In 1069–1070 (or possibly a few years later[23]), Fez was conquered by the Almoravids under Yusuf ibn Tashfin. In the same year of this conquest, Yusuf ibn Tashfin finally unified Madinat Fas and Al-'Aliya into one city. The walls dividing them were destroyed, bridges connecting them were built or renovated, and a new circuit of walls was constructed that encompassed both cities. A kasbah (citadel) was built at the western edge of the city (just west of Bab Bou Jeloud today) to house the city's governor and garrison.[12][25] Under Almoravid patronage the largest expansion and renovation of the Great Mosque of al-Qarawiyyin took place (1135–1143).[29] Although the capital was moved to Marrakesh under the Almoravids, Fez acquired a reputation for Maliki legal scholarship and remained an important centre of trade and industry.[12][13] Almoravid impact on the city's structure was such that Yusuf ibn Tashfin is sometimes considered to be the second founder of Fez.[30]

In 1145 the Almohad leader Abd al-Mu'min besieged and conquered the city during the Almohad overthrow of the Almoravids. Due to the ferocious resistance they encountered from the local population, the Almohads demolished the city's fortifications.[19][31][25] However, due to Fez's continuing economic and military importance, the Almohad caliph Ya'qub al-Mansur ordered the reconstruction of the ramparts.[32]:36[25]:606 Since the city had grown in the meantime, the new Almohad perimeter of walls was larger than that of the former Almoravid ramparts.[25]:607 The walls were completed by his successor Muhammad al-Nasir in 1204,[32] giving them their definitive shape and establishing the perimeter of Fes el-Bali to this day.[19][25][31] The Almohads built the Kasbah Bou Jeloud on the site of the former Almoravid kasbah[19] and also built the first kasbah occupying the site of the current Kasbah an-Nouar.[33][32]:109 Not all the land within the city walls was densely inhabited; much of it was still relatively open and was occupied by crops and gardens used by the inhabitants.[31]

Like many Moroccan cities, Fez was greatly enlarged during the Almohad Caliphate and saw its previously dominating rural aspect lessen. This was accomplished partly by the settling there of Andalusians and the further improvement of the infrastructure. At the start of the 13th century they broke down the Idrisid city walls and constructed new ones, which covered a much wider space. These Almohad walls exist to this day as the outline of Fes el-Bali. Under Almohad rule the city grew to become one of the largest in the world between 1170 and 1180, with an estimated 200,000 people living there.[34]

.jpg.webp)

In 1250 Fez regained its capital status under the Marinid dynasty. In 1276 after a massacre by the population to kill all Jews that was stopped by intervention of the Emir,[35] they founded Fes Jdid, which they made their administrative and military centre. Fez reached its golden age in the Marinid period.[36][12][13] It is from the Marinid period that Fez's reputation as an important intellectual centre largely dates.[37] They established the first madrasas in Morocco here in the city.[38][39] The principal monuments in the medina, the residences and public buildings, date from the Marinid period.[40] The madrasas are a hallmark of Marinid architecture, with its striking blending of Andalusian and Almohad traditions. Between 1271 and 1357 seven madrasas were built in Fez, which are considered among the best examples of Moroccan architecture and some of the most richly decorated monuments in Fez.[41][42][43]

Ibn Battuta described the city of Fez, which he passed through on his way to Sijilmasa.[44]

The Jewish quarter of Fez, the Mellah, was created in Fes el-Jdid at some point during the Marinid period. The exact date and circumstances of its formation are not firmly established,[45][46] but many scholars date the transfer of the Jewish population from Fes el-Bali to the new Mellah to the 15th century, a period of political tension and instability. In particular, Jewish sources describe the transfer as a consequence of the "rediscovery" of Idris II's body in the heart of the city in 1437, which caused the surrounding area – if not the entire city – to acquire a "holy" (haram) status, requiring that non-Muslims be removed from the area.[45][47][48][49] The Jewish community had initially consisted of indigenous local Jews but these were joined by Sephardic Jews from the Iberian Peninsula (known as the Megorashim) in subsequent generations, especially after the 1492 expulsion of Jews from Spain.[50]

The 1465 Moroccan revolt in 1465 overthrew the last Marinid sultan. In 1472 the Wattasids, another Zenata dynasty which had previously served as viziers under the Marinid sultans, succeeded as rulers of Morocco from Fez.[17][51] They faithfully (but for a large part unsuccessfully) continued Marinid policies.[52]

Sharifian rule: under the Saadians and Alaouites

In the 16th century the Saadis rose to power in southern Morocco and challenged the Wattasids. In the meanwhile, the Ottoman Empire came close to Fez after the conquest of Algeria in the 16th century.[17] In January 1549 the Saadi sultan Mohammed ash-Sheikh took Fez and ousted the last Wattasid sultan Ali Abu Hassun. They later retook the city in 1553 with Ottoman support, but this reconquest was short-lived and in 1554 the Wattasids were decisively defeated in the battle of Tadla by the Saadis. The Ottomans would try to invade Morocco after the assassination of Mohammed ash-Sheikh in 1558, but were defeated by his son Abdallah al-Ghalib at the battle of Wadi al-Laban north of Fez. Hence, Morocco remained the only North-African state to deter and defeat the Ottomans.[53]

After the death of Abdallah al-Ghalib a new power struggle would emerge, after Abd al-Malik would take Fez with Ottoman support and oust his nephew Abu Abdullah. The latter would flee to Portugal where he asked king Sebastian of Portugal for help to regain his throne. This would lead to the Battle of Alcacer Quibir where Abd al-Malik's army would defeat the invading Portuguese army with the support of his Ottoman allies, ensuring Moroccan independence. Abd al-Malik himself also died during the battle and would be succeeded by Ahmad al-Mansur.[54]

The Saadians, who used Marrakesh again as their capital, did not lavish much attention on Fez, with the exception of the ornate ablutions pavilions added to the Qarawiyyin Mosque's courtyard during their time.[29] Perhaps as a result of persistent tensions with the city's inhabitants, the Saadians built a number of new forts and bastions around the city which appear to have been aimed at keeping control over the local population. They were mostly located on higher ground overlooking Fes el-Bali, from which they would have been easily able to bombard the city with canons.[19][31] These include the Kasbah Tamdert, just inside the city walls near Bab Ftouh, and the forts of Borj Nord (Borj al-Shamali) on the hills to the north, Borj Sud (Borj al-Janoub) on the hills to the south, and the Borj Sheikh Ahmed to the west, at a point in Fes el-Jdid's walls that was closest to Fes el-Bali. These were built in the late 16th century, mostly by Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur.[31][19] Two other bastions, Borj Twil and Borj Sidi Bou Nafa', were also built along Fes el-Jdid's walls south of Borj Sheikh Ahmed.[19] The Borj Nord, Borj Sud, and these bastions (sometimes referred to as the bastioun in Arabic) of Fes el-Jdid are the only fortifications in Fez to demonstrate clear European (most likely Portuguese) influence in their design, updated to serve as defenses in the age of gunpowder. Some of them may have been built with the help of Christian European prisoners of war from the Saadians' victory over Portuguese at the Battle of the Three Kings in 1578.[31][55]

After the long and impressive reign of Ahmad al-Mansur, the Saadian state fell into civil war between his sons and potential successors. Fez became a rival seat of power for a number of brothers vying against other family members ruling from Marrakesh, and both cities changed hands multiple times until the realm the internecine conflict finally ended in 1627.[54][51] Despite the reunification of the country, the Saadians were in full decline and Fez had already suffered considerably from the repeated conquests and reconquests during the conflict.[23]

It was only when the founder of the Alaouite dynasty, Moulay Rashid, took Fez in 1666 that the city saw a revival and became the capital again, albeit briefly.[31] Moulay Rashid set about restoring the city after a long period of neglect. He built the Kasbah Cherarda (also known as the Kasbah al-Khemis) to the north of Fes el-Jdid and of the Royal Palace in order to house a large part of his tribal troops.[19][31] He also restored or rebuilt what became known as the Kasbah an-Nouar, which became the living quarters of his followers from the Tafilalt region (the Alaouite dynasty's ancestral home). For this reason, the kasbah was also known as the Kasbah Filala ("Kasbah of the people from Tafilalt").[19] Moulay Rashid also built a large new madrasa, the Cherratine Madrasa, in 1670.[42] After his death Fez underwent another dark period. Moulay Isma'il, his successor, apparently disliked the city – possibly due to a rebellion there in his early reign[12] – and chose nearby Meknès as his capital instead. Although he did restore or rebuild some major monuments in the city, such as the Zawiya of Moulay Idris II, he also frequently imposed heavy taxes on the city's inhabitants and sometimes even forcibly transferred parts of its population to repopulate other cities in the country.[12] After his death things only worsened as Morocco plunged into anarchy and decades of conflict between his sons who vied to succeed him. Fez suffered particularly from repeated conflicts with the Udayas (or Oudayas), a guich tribe (vassal tribe serving as a garrison and military force) previously installed in the Kasbah Cherarda by Moulay Isma'il. Sultan Moulay Abdallah, who reigned intermittently during this period and used Fez as a capital, was initially welcomed in 1728–29 as an enemy of the Udayas, but relations between him and the city's population quickly soured due to his choice of governor. He immediately built a separate fortified palace in the countryside, Dar Dbibegh, where he resided instead. For nearly three more decades the city remained in more or less perpetual conflict with both the Udayas and the Alaouite sultans.[12]

Starting with the reign of Moulay Muhammad ibn Abdallah, between 1757 and 1790, the country stabilized and Fez finally regained its fortunes. Although its status was partly shared with Marrakesh, it remained the capital of Morocco for the rest of the Alaouite period up to the 20th century.[12][13] There was a brief period of disorder under Moulay Yazid (ruled 1790–1792) and Moulay Slimane (ruled 1792–1822), with the sultans in Fez losing control of most of the rest of Morocco between 1790 and 1795.[17]:241–242 Otherwise, however, the city benefitted from a long era of relative peace. It remained a major economic center of the region even during troubled times.[12] The Alaouites continued to rebuild or restore various monuments, as well as to expand the grounds of the Royal Palace a number of times.[42][56] The sultans and their entourage also became more and more closely associated with the elites of Fez and other urban centers, with the ulama (religious scholars) of Fez being particularly influential. After Moulay Slimane's death powerful Fassi families became the main players of the country's political and intellectual scene.[17]:242–247

Until the 19th century the city was the only source of fezzes (also known as the tarboosh).[11] Then manufacturing began in France and Turkey as well. Originally, the dye for the hats came from a berry that was grown outside the city, known as the Turkish kızılcık or Greek akenia (Cornus mas). Fez was also the end of a north–south gold trading route from Timbuktu. Fez was a prime manufacturing location for embroidery and leather goods such as the Adarga.

The Tijani Sufi order, started by Ahmad al-Tijani (d. 1815), had its spiritual center in Fez after al-Tijani moved here from Algeria in 1789.[17]:244 The order spread quickly among the literary elite of North West Africa and its ulama had significant religious, intellectual, and political influence in Fez and beyond.[57]

The last major change to Fez's topography before the 20th century was made during the reign of Moulay Hasan I (1873-1894), who finally connected Fes el-Jdid and Fes el-Bali by building a walled corridor between them.[19][31] Within this new corridor, between the two cities, were built new gardens and summer palaces used by the royals and the capital's high society, such as the Jnan Sbil Gardens and the Dar Batha palace.[19][56] Moulay Hassan also expanded the old Royal Palace itself, extending its entrance up to the current location of the Old Mechouar while adding the New Mechouar, along with the Dar al-Makina, to the north. This had the consequence of also splitting the Moulay Abdallah neighbourhood to the northwest from the rest of Fes el-Jdid.[56]

Fez played a central role in the Hafidhiya, the brief civil war that erupted when Sultan Abd al-Hafid challenged his heavily Europe-allied brother Abdelaziz for the throne.[58] A few years later the French Colonel Charles Émile Moinier arrived in Fez in 1911 and established itself at Dar Dbibegh.[23][17]:313 Moinier established himself in Fez and protected Sultan Abd al-Hafid from threats, including the pretension of Ahmed al-Hiba, son of Ma al-'Aynayn, to the sultanate.[17]:370

Colonial rule, independence, and present day

.jpg.webp)

In 1912 French colonial rule was instituted over Morocco following the Treaty of Fes. One immediate consequence was the 1912 riots in Fez, a popular uprising which included deadly attacks targeting Europeans as well as native Jewish inhabitants in the Mellah, followed by an even deadlier repression.[59][60] Fez and its Dar al-Makhzen ceased to be the center of power in Morocco as the capital was moved to Rabat, which remained the capital even after independence in 1956.[31]

A number of social and physical changes took place at this period and across the 20th century. Starting under French resident general Hubert Lyautey, one important policy with long-term consequences was the decision to largely forego redevelopment of existing historic walled cities in Morocco and to intentionally preserve them as sites of historic heritage, still known today as "medinas". Instead, the French administration built new modern cities (the Villes Nouvelles) just outside the old cities, where European settlers largely resided with modern Western-style amenities. This was part of a larger "policy of association" adopted by Lyautey which favoured various forms of indirect colonial rule by preserving local institutions and elites, in contrast with other French colonial policies that had favoured "assimilation".[61][62][63] The existence today of a Ville Nouvelle ("New City") alongside a historic medina in Fez was thus a consequence of this early colonial decision-making. The Ville Nouvelle also became known as Dar Dbibegh by Moroccans, as the former palace of Moulay Abdallah was located in the same area.[23]

.jpg.webp)

The creation of the separate French Ville Nouvelle to the west had a wider impact on the entire city's development.[63] While new colonial policies preserved historic monuments, it also had other consequences in the long-term by stalling urban development in these heritage areas.[61] Scholar Janet Abu-Lughod has argued that these policies created in Morocco a kind of urban "apartheid" between the indigenous Moroccan urban areas – which were forced to remain stagnant in terms of urban development and architectural innovation – and the new planned cities which were mainly inhabited by Europeans and which expanded to occupy lands formerly used by Moroccans outside the city.[64][65][61] This separation was partly softened, however, by wealthy Moroccans who started moving into the Ville Nouvelles during this period.[66][13] By contrast, the old city (medina) of Fez was increasingly settled by poorer rural migrants from the countryside.[13]:26

Fez also played a role in the Moroccan nationalist movement and in protests against the French colonial regime. Many Moroccan nationalists received their education at the Al-Qarawiyyin University and some of their informal political networks were established thanks to this shared educational background.[67]:140, 146 In July 1930, the Al-Qarawiyyin's students and other inhabitants participated in protests against the Berber Dahir decreed by the French authorities in May of that year.[68][67]:143–144 In 1937 the Al-Qarawiyyin mosque and R'cif Mosque were some of the rallying points for demonstrations in response to a violent crackdown on Moroccan protesters in the nearby city of Meknes, which ended with French troops being deployed across Fes el-Bali and at the mosques themselves.[69]:387–389[67]:168 Towards the end of World War II, Moroccan nationalists gathered in Fez to draft a demand for independence which they submitted to the Allies on January 11, 1944. This resulted in the arrest of nationalist leaders followed by the violent suppression of protests across many cities, including Fez.[70][67]:255

After Morocco regained its independence in 1956 many of the trends begun under colonial rule continued and accelerated during the second half of the 20th century.[70] Much of Fez's bourgeois classes moved to the growing metropolises of Casablanca and the capital, Rabat.[13][70] The Jewish population was particularly depleted, either moving to Casablanca or emigrating to countries like France, Canada, and Israel. Although the population of the city grew, it did so only slowly up until the late 1960s, when the pace of growth finally accelerated.[70]:216 Throughout this period (and up to today) Fez nonetheless remained the country's third largest urban center.[13]:26[70]:216 Between 1971 and 2000, the population of the city roughly tripled from 325,000 to 940,000.[14]:376 The Ville Nouvelle became the locus of further development, with new peripheral neighbourhoods – with inconsistent housing quality – spreading outwards around it.[70] In 1963 the University of Al-Qarawiyyin was reorganized as a state university,[71] while a new public university, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, was founded in 1975 in the Ville Nouvelle.[72] In 1981, the old city, consisting of Fes el-Bali and Fes Jdid, was classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[73]

During this period, however, Moroccans were also subject to serious social inequalities and economic precarity, particularly under the repressive reign of King Hassan II (known as the Years of Lead). Austerity measures led to several riots and uprisings across other cities during the 1980s. In 1990 the population of Fez broke into protest and rioting in turn, led by university students and youths. The events began with a strike called to demand an increase to minimum wage and other measures. The death of one of the students further inflamed protests, resulting in buildings being burned and looted, particularly symbols of wealth such as the Hôtel des Mérinides, a luxury hotel overlooking Fes el-Bali and dating to the time of Lyautey. While the official death toll was 5 people, the New York Times reported a toll of 33 people and quoted an anonymous source claiming the real death toll was likely higher. The government denied reports that the deaths were due to the intervention of security forces and armored vehicles.[14]:377[74][75]

Today Fez remains a regional capital and one of Morocco's most important cities. It is also a major tourism destination due to its historical heritage. In recent years efforts have been underway to restore and rehabilitate the old medina, ranging from the restoration of individual monuments to attempts to rehabilitate the Fez River.[76][77][78][79]

Geography

Location

The city is divided between its historic medina (the two walled districts of Fes el-Bali and Fes el-Jdid) and the now much large Ville Nouvelle (New City) along with several outlying modern neighbourhoods. The old city is located in a valley along the banks of the Oued Fes (Fez River) just above its confluence with the larger Sebou River to the northeast.[12][11] The Fez River takes its sources from the south and west and is split into various small canals which provide the historic city with water. These in turn empty into the Oued Bou Khareb, the stretch of the river which passes through the middle of Fes el-Bali and separates the Qarawiyyin quarter from the Andalusian quarter.[12]

The new city occupies a plateau on the edge of the Saïs plain. The latter stretches out to the west and south and is occupied largely by farmland. Roughly 15 km south of Fes el-Bali is the region's main airport, Fes-Saïs. Further south is the town of Sefrou, while the city of Meknes, the next largest city in the region, is located to the southwest.[80][81]

Climate

Located by the Atlas Mountains, Fez has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa) with a strong continental influence, shifting from relatively cool and wet in the winter to dry and hot days in the summer months between June and September. Rainfall can reach up to 800 mm (31 in) in good years. The winter highs typically reach around 15 °C (59 °F) in December–January. Frost is not uncommon during the winter period. The highest and lowest temperatures ever recorded in the city are 46.7 °C (116 °F) and −8.2 °C (17 °F), respectively.(see weather-table below). Fez's climate is strongly similar to that of Seville and Córdoba, Andalusia, Spain. Snowfall on average occurs once every 3 to 5 years. Fez recorded snowfall in three straight years in 2005, 2006 and 2007.[82][83][84][85]

| Climate data for Fez | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 25.0 (77.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

37.0 (98.6) |

40.8 (105.4) |

44.0 (111.2) |

46.7 (116.1) |

44.4 (111.9) |

41.7 (107.1) |

37.5 (99.5) |

31.2 (88.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

46.7 (116.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.1 (59.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

19.7 (67.5) |

23.9 (75.0) |

28.5 (83.3) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.8 (92.8) |

30.4 (86.7) |

24.7 (76.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

15.7 (60.3) |

23.3 (73.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.4 (48.9) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

17.1 (62.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.1 (64.6) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

16.6 (61.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.7 (38.7) |

5.0 (41.0) |

5.9 (42.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −8.2 (17.2) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.9 (40.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 72.2 (2.84) |

100.4 (3.95) |

93.6 (3.69) |

87.7 (3.45) |

53.0 (2.09) |

24.4 (0.96) |

3.0 (0.12) |

3.6 (0.14) |

17.0 (0.67) |

62.3 (2.45) |

89.1 (3.51) |

85.2 (3.35) |

691.5 (27.22) |

| Average rainy days | 12.1 | 13.2 | 13.5 | 13.5 | 10.2 | 5.3 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 4.7 | 9.1 | 12.7 | 12.1 | 109.8 |

| Average snowy days | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 60 | 55 | 58 | 62 | 64 | 71 | 79 | 77 | 75 | 64 | 60 | 60 | 65 |

| Source 1: Hong Kong Observatory[86] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meoweather.com,[85] Voodoo skies for extremes[84] Weather Atlas [87] NOAA [88] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Fez | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 6.8 |

| Source: Weather Atlas [87] | |||||||||||||

Subdivisions

The prefecture is divided administratively into the following:[89]

| Name | Geographic code | Type | Households | Population (2014) | Foreign population | Moroccan population | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agdal | 231.01.01. | Arrondissement | 37421 | 142407 | 1457 | 140950 | |

| Mechouar Fes Jdid | 231.01.03. | Municipality | 5416 | 20560 | 23 | 20537 | |

| Saiss | 231.01.05. | Arrondissement | 48983 | 207345 | 1413 | 205932 | |

| Fes-Medina | 231.01.07. | Arrondissement | 17342 | 70592 | 212 | 70380 | |

| Jnan El Ouard | 231.01.09. | Arrondissement | 43333 | 201011 | 47 | 200964 | |

| El Mariniyine | 231.01.11. | Arrondissement | 47898 | 209494 | 109 | 209385 | |

| Zouagha | 231.01.11. | Arrondissement | 57346 | 260663 | 254 | 260409 | |

| Oulad Tayeb | 231.81.01. | Rural commune | 4626 | 24594 | 6 | 24588 | 14187 residents live in the center, called Ouled Tayeb; 1407 residents live in rural areas. |

| Ain Bida | 231.81.03. | Rural commune | 1443 | 7843 | 0 | 7843 | |

| Sidi Harazem | 231.81.05. | Rural commune | 1228 | 5622 | 0 | 5622 | 3509 residents live in the center, called Skhinate; 2113 residents live in rural areas. |

Demographics

According to the 2014 national census, the population of Fez was 1,150,131, including suburbs and satellite villages such as Sidi Harazem. Most of this population was Moroccan, but it also included 3521 resident foreigners. The majority of the population lives in the Ville Nouvelle region and other modern-day neighbourhoods outside the historic walled city.[89]

Economy

Historically, the city was one of Morocco's main centers of trade and craftsmanship. The tanning industry, for example, still embodied by tanneries of Fes el-Bali today, was a major source of exports and economic sustenance since the city's early history.[90] Up until the late 19th century, the city was the only place in the world which fabricated the fez hat.[11] The city's commerce was concentrated along its major streets, like Tala'a Kebira, and around the central bazaar known as the Kissariat al-Kifah from which many other souqs (markets) branched off.[12][13] The crafts industry continues to this day and is still focused in the old city.[11]

Today, the city's surrounding countryside, the fertile Saïss plains, is an important source of agricultural activity producing primarily cereals, beans, olives, and grapes, as well as raising livestock.[11][91] Tourism is also a major industry due to the city's UNESCO-listed historic medina.[11] Religious tourism is also present due to the old city's many major zawiyas (Islamic shrines), such as the Zawiya of Moulay Idris II and the Zawiya of Sidi Ahmed al-Tijani, which attract both Moroccan and international (especially West African) pilgrims.[92] The city and the region still struggle with unemployment and economic precarity.[93]

Landmarks

Medina of Fez

The historic city of Fez consists of Fes el-Bali, the original city founded by the Idrisid dynasty on both shores of the Oued Fes (River of Fez) in the late 8th and early 9th centuries, and the smaller Fez el-Jdid, founded on higher ground to the west in the 13th century. It is distinct from Fez's now much larger Ville Nouvelle (new city) originally founded by the French. Fes el-Bali is the site of the famous Qarawiyyin University and the Mausoleum of Moulay Idris II, the most important religious and cultural sites, while Fez el-Jdid is the site of the enormous Royal Palace, still used by the King of Morocco today. These two historic cities are linked together and are usually referred to together as the "medina" of Fez, though this term is sometimes applied more restrictively to Fes el-Bali only.[lower-alpha 1] Fez is becoming an increasingly popular tourist destination and many non-Moroccans are now restoring traditional houses (riads and dars) as second homes in the medina. Fez is also considered the cultural and spiritual capital of Morocco.[94] In 1981, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) proclaimed Medina of Fez a World Cultural Heritage site, as "[they] include a considerable number of religious, civil and military monuments that brought about a multi-cultural society. This architecture is characterised by construction techniques and decoration developed over a period of more than ten centuries, and where local knowledge and skills are interwoven with diverse outside inspiration (Andalusian, Middle Eastern and African). The Medina of Fez is considered as one of the most extensive and best conserved historic towns of the Arab-Muslim world."[95]

Places of worship

.jpg.webp)

There are numerous historic mosques in the medina, some of which are part of a madrasa or zawiya. Among the oldest mosques still standing today are the highly prestigious Mosque of al-Qarawiyyin, founded in 857 (and subsequently expanded),[96] the Mosque of the Andalusians founded in 859–860,[97] the Bou Jeloud Mosque from the late 12th century,[98] and possibly the Mosque of the Kasbah en-Nouar (which may have existed in the Almohad period but was likely rebuilt much later[94][12]). The very oldest mosques of the city, dating back to its first years, were the Mosque of the Sharifs (or Shurafa Mosque) and the Mosque of the Sheikhs (or al-Anouar Mosque); however, they no longer exist in their original form. The Mosque of the Sharifs was the burial site of Idris II and evolved into the Zawiya of Moulay Idris II that exists today, while the al-Anouar Mosque has left only minor remnants.[12] A number of mosques from the important Marinid era, when Fes el-Jdid was created to be the capital of Morocco, include the Great Mosque of Fez el-Jdid from 1276, the Abu al-Hassan Mosque from 1341,[99] the Chrabliyine Mosque from 1342,[100] the al-Hamra Mosque from around the same period (exact date unconfirmed),[43] and the Bab Guissa Mosque, also from the reign of Abu al-Hasan (1331-1351) but modified in later centuries.[42] Other major mosques from the more recent Alaouite period are the Moulay Abdallah Mosque, built in the early to mid-18th century with the tomb of Sultan Moulay Abdallah,[43] and the R'cif Mosque, built in the reign of Moulay Slimane (1793-1822).[101] The Zawiya of Moulay Idriss II (previously mentioned) and the Zawiya of Sidi Ahmed al-Tijani include mosque areas as well, as do several other prominent zawiyas in the city.[94][12] The Ville Nouvelle (New City) also includes many modern mosques.

Elsewhere, the Jewish quarter (Mellah) is the site of the 17th-century Al-Fassiyin Synagogue and Ibn Danan Synagogue, as well multiple other lesser-known synagogues, though none of them are functioning today.[13][102][103] According to the World Jewish Congress there were only 150 Moroccan Jews remaining in Fes.[104] Fez also contains one Catholic church, the Church of Saint Francis of Assisi. First established in 1919 or 1920, during the French colonial period, the current building was built in 1928 and expanded in 1933. Today it is part of the Archdiocese of Rabat, and it was most recently restored in 2005.[105][106][107]

Madrasas

The city has traditionally retained the influential position as a religious capital in the region, exemplified by the Madrasa (or University) of al-Qarawiyyin which was established in 859 by Fatima al-Fihri originally as a mosque. The madrasa is the oldest existing and continually operating degree-awarding educational institution in the world according to UNESCO and Guinness World Records.[108][73] The Marinid dynasty (13th-15th century) devoted great attention to the construction of madrasas following the Maliki orthodoxy, resulting in the unprecedented prosperity of the city's religious institutions. The first madrasa built during the Marinid era was the Saffarin Madrasa in Fes el-Bali by Sultan Abu Yusuf in 1271.[41]:312 Sultan Abu al-Hassan was the most prolific patron of madrasa construction, completing the Al-Attarine, Mesbahiyya and Sahrij Madrasa in Fez alone, and several other madrasas as well in other cities such as Salé and Meknes. His son Abu Inan Faris built the famed Bou Inania Madrasa, and by the time of his death, every major city in the Marinid Empire had at least one madrasa.[109] The library of the Madrasa of al-Qarawiyyin was also established under Marinid rule around 1350, which stores a large selection of valuable manuscripts dating back to the medieval era.[94] The largest madrasa in the medina is Cherratine Madrasa commissioned by the Alaouite sultan Al-Rashid in 1670, which is the only major non-Marinid foundation besides the Madrasa of al-Qarawiyyin.[110]

Fortifications

City walls and gates

The entire medina of Fez was heavily fortified with crenelated walls with watchtowers and gates, a pattern of urban planning which can be seen in Salé and Chellah as well.[109] City walls were placed into the current positions during the 11th century, under the Almoravid rule. During this period, the two formerly divided cities known as Madinat Fas and al-'Aliya were united under a single enclosure. The Almoravid fortifications were later destroyed and then rebuilt by the Almohad dynasty in the 12th century, under Caliph Muhammad al-Nasir.[12] The oldest sections of the walls today thus date back to this time.[13] These fortifications were restored and maintained by the Marinid dynasty from the 12th to 16th centuries, along with the founding of the royal citadel-city of Fes el-Jdid.[111] Construction of the new city's gates and towers sometimes employed the labour of Christian prisoners of war.[109]

The gates of Fez, scattered along the circuit of walls, were guarded by the military detachments and shut at night.[109] Some of the main gates have existed, in different forms, since the earliest years of the city.[12] The oldest gates today, and historically the most important ones of the city, are Bab Mahrouk (in the west), Bab Guissa (in the northeast), and Bab Ftouh (in the southeast).[12][13] After the foundation of Fes Jdid by the Marinids in the 13th century, new walls and three new gates such as Bab Dekkakin, Bab Semmarine, and Bab al-Amer were established along its perimeter.[112][113] Later, in modern times, the gates became more ceremonial rather than defensive structures, as reflected by the 1913 construction of the decorative Bab Bou Jeloud gate at the western entrance of Fes el-Bali by the French colonial administration.[13]

Forts and kasbahs

Along with the city walls and gates, several forts were constructed along the defensive perimeters of the medina during the different time periods. The military watchtowers built in its early days during the Idrisid era were relatively small. However, the city rapidly developed as the military garrison center of the region during the Almoravid era, in which the military operations were commanded and carried out to other North African regions and Southern Europe to the north, and Senegal river to the south. Subsequently, it led to the construction of numerous forts, kasbahs, and towers for both garrison and defense. A "kasbah" in the context of Maghrebi region is the traditional military structure for fortification, military preparation, command and control. Some of them were occupied as well by citizens, certain tribal groups, and merchants. Throughout the history, 13 kasbahs were constructed surrounding the old city.[114] Among the most prominent among them is the Kasbah An-Nouar, located at the western or north-western tip of Fes el-Bali, which dates back to the Almohad era but was restored and repurposed under the Alaouites.[12] Today, it is an example of a kasbah serving as a residential district much like the rest of the medina, with its own neighborhood mosque. The Kasbah Bou Jeloud, which no longer exists as a kasbah today, was once the governor's residence and stood near Bab Bou Jeloud, south of the Kasbah an-Nouar.[12] It too had its own mosque, known as the Bou Jeloud Mosque. Other kasbahs include the Kasbah Tamdert, built by the Saadis near Bab Ftouh, and the Kasbah Cherarda, built by the Alaouite sultan Moulay al-Rashid just north of Fes Jdid.[13][12] Kasbah Dar Debibagh is one of the newest kasbahs, built in 1729 during the Alaouite era at 2 km from the city wall in a strategic position.[114][115] The Saadis also built a number of strong bastions in the late 16th century to assert their control over Fez, including notably the Borj Nord which is among the largest strictly military structures in the city and now refurbished as a military museum.[116] Its sister fort, Borj Sud, is located on the hills to the south of the city.[12]

Tanneries

Since the inception of the city, tanning industry has been continually operating in the same fashion as it did in the early centuries. Today, the tanning industry in the city is considered one of the main tourist attractions. There are three tanneries in the city, largest among them is Chouara Tannery near the Saffarin Madrasa along the river. The tanneries are packed with the round stone wells filled with dye or white liquids for softening the hides. The leather goods produced in the tanneries are exported around the world.[117][118][119] The two other major tanneries are the Sidi Moussa Tannery to the west of the Zawiya of Moulay Idris II and the Ain Azliten Tannery in the neighbourhood of the same name on the northern edge of Fes el-Bali.[12]:220

Tombs and mausoleums

Located in the heart of Fes el-Bali, the Zawiya of Moulay Idriss II is a zawiya (a shrine and religious complex; also spelled zaouia), dedicated to and containing the tomb of Idris II (or Moulay Idris II when including his sharifian title) who is considered the main founder of the city of Fez.[120][121] Another well-known and important zawiya is the Zawiyia of Sidi Ahmed al-Tijani, which commemorates Sidi Ahmed al-Tijani, the founder of Tijaniyyah tariqa from the 18th century.[122] A number of zawiyas are scattered elsewhere across the city, many containing the tombs of important Sufi saints or scholars, such as the Zawiya of Sidi Abdelkader al-Fassi, the Zawiya of Sidi Ahmed esh-Shawi, and the Zawiya of Sidi Taoudi Ben Souda.[123]

The old city also has several major historic cemeteries which existed outside the main city gates, namely the cemeteries of Bab Ftouh (the most significant), Bab Mahrouk, and Bab Guissa. Some of these cemeteries include marabouts or domed structures containing the tombs of local Muslim saints (often considered Sufis). One of the most important ones is the Marabout of Sidi Harazem in the Bab Ftouh Cemetery.[12] To the north, near the Bab Guissa Cemetery, there are also the Marinid Tombs built during the 14th century as a necropolis for the Marinid sultans, ruined today but still a well-known landmark of the city.[13]

Gardens

The Jnane Sbile Garden was created as a royal park and garden in the 19th century by Sultan Moulay Hassan I (ruled 1873-1894) between Fes el-Jdid and Fes el-Bali.[13]:296[12]:100 Today it is the oldest garden of Fes.[124] Many bourgeois and aristocratic mansions were also accompanied by private gardens, especially in the southwestern part of Fes el-Bali, an area once known as al-'Uyun.[12] Other gardens also exist within the grounds of the historic royal palaces of the city, such as the Agdal and Lalla Mina Gardens in the Dar al-Makhzen or the gardens of the Dar al-Beida (originally attached to Dar Batha).[13][12][125]

Funduqs/foundouks (historic merchant buildings)

The old city of Fez includes more than a hundred funduqs or foundouks (traditional inns, or urban caravanserais). These were commercial structures which provided lodging for merchants and travelers or housed the workshops of artisans.[12]:318 They also frequently served as venues for other commercial activities such as markets and auctions.[12] One of the most famous is the Funduq al-Najjariyyin, which was built in the 18th century by Amin Adiyil to provide accommodation and storage for merchants and which now houses the Nejjarine Museum of Wooden Arts & Crafts.[126][125] Other major important examples include the Funduq Shamma'in (also spelled Foundouk Chemmaïne) and the Funduq Staouniyyin (or Funduq of the Tetouanis), both dating from the Marinid era or earlier, and the Funduq Sagha which is contemporary with the Funduq al-Najjariyyin.[12][42][127][128]

Hammams (bathhouses)

.jpg.webp)

Fez is also notable for having preserved a great many of its historic hammams (public bathhouses in the Muslim world), thanks in part to their continued usage by locals up to the present day.[130][131][132] Notable examples, all dating from around the 14th century, include the Hammam as-Saffarin, the Hammam al-Mokhfiya, and the Hammam Ben Abbad.[133][130][131] They were generally built next to a well or natural spring which provided water, while the sloping topography of the city allowed for easy drainage.[130] The layout of the traditional hammam in the region was inherited from the Roman bathhouse model. The first major room visitors entered was the undressing room (mashlah in Arabic or goulsa in the local Moroccan Arabic dialect), equivalent to the Roman apodyterium. From the undressing room visitors proceeded to the bathing/washing area which consisted of three rooms: the cold room (el-barrani in the local Arabic dialect; equivalent to the frigidarium), the middle room or warm room (el-wasti in Arabic; equivalent to the tepidarium), and the hot room (ad-dakhli in Arabic; equivalent to the caldarium).[130][131] Though their architecture can be very functional, some of them, like the Hammam as-Saffarin and the Hammam al-Mokhfiya, have notable decoration. Although they are architecturally not very prominent from the exterior, they are recognizable from the rooftops by their pierced domes and vaults which usually covered the main chambers.[130] The warm and hot rooms were heated using a traditional hypocaust system just as Roman bathhouses did, with furnaces usually located behind the hot room. Fuel was provided by wood but also by recycling the waste by-products of other industries in the city such as wood shavings from carpenters' workshops and olive pits from the nearby olive presses. This traditional system continued to be used even up to the 21st century.[130]

Historic palaces and residences

.jpg.webp)

Many old private residences have also survived to this day, in various states of conservation. One type of house known, centered around an internal courtyard, is known as a riad.[13] Such private houses include the Dar al-Alami,[134] the Dar Saada (now a restaurant), Dar 'Adiyil, Dar Belghazi, and others.[13] Larger and richer mansions, such as the Dar Mnebhi, Dar Moqri, and Palais Jamaï (Jamai Palace), have also been preserved.[13] Numerous palaces and riads are now utilized as hotels for the tourism industry. The Palais Jamai, for example, was converted into a luxury hotel in the early 20th century.[135][13] The lavish former mansion of the Glaoui clan, known as the Dar Glaoui, is partly open to visitors but still privately owned.[136]

As a former capital, the city contains several royal palaces as well. Dar Batha is a former palace completed by the Alaouite Sultan Moulay Abdelaziz (ruled 1894-1908) and turned into a museum in 1915 with around 6,000 pieces.[12][137] A large area of Fes el-Jdid is also taken up by the 80-hectare Royal Palace, or Dar al-Makhzen, whose new ornate gates (built in 1969-71) are renowned but whose grounds are not open to the public as they are still used by the King of Morocco when visiting the city.[125]

Education

Universities

The University of al-Qarawiyyin is considered by some to be the oldest continually-operating university in the world.[138][139] The university was first founded as a mosque by Fatima al-Fihri in 859 which subsequently became one of the leading spiritual and educational centers of the historic Muslim world.[71] It became a state university in 1963, and remains an important institution of learning today.[140]

Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University is a public university founded in 1975 and is the largest in the city by attendance, counting over 86,000 students in 2020.[72][141][142] It has 12 faculties with sites across the city, with two main campuses known as Dhar El Mehraz and Sais.[141] Another public university, the Euromed University of Fez, was created in 2012 and is certified by the Union for the Mediterranean.[143][144]

The city's first private university, the Private University of Fez, was created in 2013 out of the École polytechnique de Technologie founded 5 years earlier.[145] Its main focus is its engineering school,[146] though it also offers diplomas in architecture, business, and law.[147]

Transport

The city is served by the region's main international airport, Fès–Saïs, located roughly 15 km south of the city center.[80] A new terminal was added to the airport in 2017 which expanded the airport's capacity to 2.5 million visitors a year.[148]

The city's main train station, operated by ONCF, is located s short distance from the downtown area of the Ville Nouvelle and is connected to the rail lines running east to Oujda and west to Tangier and Casablanca.[149][80] The main intercity bus terminal (or gare routière) is located just north of Bab Mahrouk, on the outskirts of the old medina, although CTM also operates a terminal off Boulevard Mohammed V in the Ville Nouvelle. Intercity taxis (also known as grands taxis) depart from and arrive at several spots including the Bab Mahrouk bus station (for western destinations like Meknes and Rabat), Bab Ftouh (for eastern destinations like Sidi Harazem and Taza), and another lot in the Ville Nouvelle (for southern destinations like Sefrou).[80][150]

The city operates a public transit system with various bus routes.[151]

Sport

Fez has two football teams, MAS Fez (Fés Maghrebi) and Wydad de Fès (WAF). They both play in the Botola the highest tier of the Moroccan football system and play their home matches at the 45,000 seat Complexe Sportif de Fès stadium.

The MAS Fez basketball team competes in the Nationale 1, Morocco's top basketball division.

Twin towns – sister cities

Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso (1982)

Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso (1982) Chengdu, China (2015)[153]

Chengdu, China (2015)[153] Coimbra, Portugal[154]

Coimbra, Portugal[154] Córdoba, Spain (1990)[155]

Córdoba, Spain (1990)[155] East Jerusalem, Palestine (1982)

East Jerusalem, Palestine (1982) Florence, Italy (1961)

Florence, Italy (1961) Jericho, Palestine (2014)[156]

Jericho, Palestine (2014)[156] Kairouan, Tunisia (1965)

Kairouan, Tunisia (1965) Kraków, Poland (1985)

Kraków, Poland (1985) Montpellier, France (2003)

Montpellier, France (2003) Saint-Louis, Senegal (1979)

Saint-Louis, Senegal (1979) Suwon, South Korea (2003)

Suwon, South Korea (2003) Wuxi, China (2011)[157]

Wuxi, China (2011)[157] Xi'an, China (2019)[158]

Xi'an, China (2019)[158]

See also

Notes

- Medina is the Arabic word for "city", which in former French colonies in North Africa is also used to refer to the old part of a city, as the French largely generally built new cities (Ville Nouvelles) next to them and left the historic cities intact.

References

Footnotes

Citations

- "Fez, Kingdom of Morocco", Lat34North.com & Yahoo! Weather, 2009, webpages: L34-Fes Archived 2018-08-30 at the Wayback Machine and Yahoo-Fes-stats.

- Morocco 2014 Census

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Medina of Fez – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-09-20.

- "Note de présentation des premiers résultats du Recensement Général de la Population et de l'Habitat 2014" (in French). High Commission for Planning. 20 March 2015. p. 8. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- Mother Nature Network, 7 car-free cities

- "History of Fes". Archived from the original on 2011-03-16. Retrieved 2010-12-23.

- Cities of the Middle-East and North-Africa A historical enceclopedia. Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley, pagina 151.

- The Travels of Ibn Battuta

- Bigon, Liora (2016-06-06). Place Names in Africa: Colonial Urban Legacies, Entangled Histories. Springer. p. 83. ISBN 9783319324852.

- "An architectural Investigation of Marinid and Watasid Fes" (PDF). Etheses.whiterose.ac.uk. p. 19. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Fes". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. 3 Mar. 2007

- Le Tourneau, Roger (1949). Fès avant le protectorat: étude économique et sociale d'une ville de l'occident musulman. Casablanca: Société Marocaine de Librairie et d'Édition.

- Métalsi, Mohamed (2003). Fès: La ville essentielle. Paris: ACR Édition Internationale. ISBN 978-2867701528.

- Rivet, Daniel (2012). Histoire du Maroc: de Moulay Idrîs à Mohammed VI. Fayard.

- The Places Where Men Pray Together, p. 463, at Google Books p. 55

- Kennedy, Hugh (1996). Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus. Routledge. ISBN 9781317870418.

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil M.; Abun-Nasr, Abun-Nasr, Jamil Mirʻi (1987). A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521337670.

- Realm of Saints, p. 9, at Google Books

- Le Tourneau, Roger (1949). Fès avant le protectorat: étude économique et sociale d'une ville de l'occident musulman. Casablanca: Société Marocaine de Librairie et d'Édition.

- Lombard, Maurice (2009). The Golden Age of Islam. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 138. ISBN 978-1558763227.

- Eustache, D. (2012). "Idrīsids". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill.

- Terrasse, Henri (1942). La mosquée des Andalous à Fès. Paris: Les Éditions d'art et d'histoire.

- Le Tourneau, Roger; Terrasse, Henri (2012). "Fās". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill.

- Madani, Tariq (1999). "Le réseau hydraulique de la ville de Fès". Archéologie islamique. 8–9: 119–142.

- Marcos Cobaleda, Maria; Villalba Sola, Dolores (2018). "Transformations in medieval Fez: Almoravid hydraulic system and changes in the Almohad walls". The Journal of North African Studies. 23 (4): 591–623.

- Gaillard, Henri (1905). Une ville de l'Islam: Fès. Paris: J. André. pp. 32.

- Gaudio, Attilio (1982). Fès: Joyau de la civilisation islamique. Paris: Les Presse de l'UNESCO: Nouvelles Éditions Latines. ISBN 2723301591.

- "La magnifique rénovation des 27 monuments de Fès – Conseil Régional du Tourisme (CRT) de Fès" (in French). Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- Terrasse, Henri (1968). La Mosquée al-Qaraouiyin à Fès; avec une étude de Gaston Deverdun sur les inscriptions historiques de la mosquée. Paris: Librairie C. Klincksieck.

- The Almoravids and the Meanings of Jihad, p. 43, at Google Books (p.51)

- Métalsi, Mohamed (2003). Fès: La ville essentielle. Paris: ACR Édition Internationale. ISBN 978-2867701528.

- Gaillard, Henri (1905). Une ville de l'Islam: Fès. Paris: J. André.

- Gaudio, Attilio (1982). Fès: Joyau de la civilisation islamique. Paris: Les Presses de l'Unesco: Nouvelles Éditions Latines. ISBN 2723301591.

- Morocco 2009, p. 252, at Google Books (p.252)

- Roudh el-Kartas: Histoire des souverains du Maghreb, p. 459, at Google Books

- O'Meara, Simon M. (2004). An architectural Investigation of Marinid and Wattasid Fes Medina (674-961/1276-1554), in Terms of Gender, Legend, and Law (PDF). University of Leeds. pp. 16, 22.

- Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 896, at Google Books (p. 605)

- The Berbers and the Islamic State, p. 91, at Google Books (p. 90)

- Islamic Art a Visual Culture, p. 121, at Google Books (p. 121)

- 'http://www.al-hakawati.net/english/Cities/fez.asp Archived 2013-06-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Kubisch, Natascha (2011). "Maghreb - Architecture" in Hattstein, Markus and Delius, Peter (eds.) Islam: Art and Architecture. h.f.ullmann.

- Touri, Abdelaziz; Benaboud, Mhammad; Boujibar El-Khatib, Naïma; Lakhdar, Kamal; Mezzine, Mohamed (2010). Le Maroc andalou : à la découverte d'un art de vivre (2 ed.). Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Royaume du Maroc & Museum With No Frontiers. ISBN 978-3902782311.

- Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. p. 281. ISBN 9780330418799.

- García-Arenal, Mercedes (1987). "Les Bildiyyīn de Fès, un groupe de néo-musulmans d'origine juive". Studia Islamica. 66: 113–143.

- Rguig, Hicham (2014). "Quand Fès inventait le Mellah". In Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (eds.). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Paris: Louvre éditions. pp. 452–454. ISBN 9782350314907.

- Zafrani, H. "Mallāḥ". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill.

- Gilson Miller, Susan; Petruccioli, Attilio; Bertagnin, Mauro (2001). "Inscribing Minority Space in the Islamic City: The Jewish Quarter of Fez (1438-1912)". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 60 (3): 310–327. doi:10.2307/991758. JSTOR 991758.

- Ben-Layashi, Samir; Maddy-Weitzman, Bruce (2018). "Myth, History, and Realpolitik: Morocco and its Jewish Community". In Abramson, Glenda (ed.). Sites of Jewish Memory: Jews in and From Islamic Lands. Routledge. ISBN 9781317751601.

- Chetrit, Joseph (2014). "Juifs du Maroc et Juifs d'Espagne: deux destins imbriqués". In Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (eds.). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Paris: Louvre éditions. pp. 309–311. ISBN 9782350314907.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2004). The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press.

- "An architectural Investigation of Marinid and Watasid Fes" (PDF). Etheses.whiterose.ac.uk. p. 5. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "3. North Africa, 1504-1799. 2001. The Encyclopedia of World History". 19 December 2007. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Véronne, Chantal de la (2012). "Saʿdids". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill.

- Salmon, Xavier (2016). Marrakech: Splendeurs saadiennes: 1550-1650. Paris: LienArt. p. 92. ISBN 9782359061826.

- Bressolette, Henri (2016). A la découverte de Fès. L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2343090221.

- Brigaglia, Andrea (2013–2014). "Sufi Revival and Islamic Literacy: Tijaniyya Writings in Twentieth-Century Nigeria". Annual Review of Islam in Africa. 12 (1).

- Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 76. ISBN 9781139624695. OCLC 855022840.

- Gershovich, Moshe (2000). "Pre-Colonial Morocco: Demise of the Old Mazhkan". French Military Rule in Morocco: colonialism and its consequences. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-4949-X.

- H. Z(J. W.) Hirschberg (1981). A history of the Jews in North Africa: From the Ottoman conquests to the present time, edited by Eliezer Bashan and Robert Attal. BRILL. p. 318. ISBN 90-04-06295-5.

- Wagner, Lauren; Minca, Claudio (2014). "Rabat retrospective: Colonial heritage in a Moroccan urban laboratory". Urban Studies. 51 (14): 3011–3025.

- Holden, Stacy E. (2008). "The Legacy of French Colonialism: Preservation in Morocco's Fez Medina". APT Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology. 39 (4): 5–11.

- Jelidi, Charlotte (2012). Fès, la fabrication d'une ville nouvelle (1912-1956). ENS Éditions.

- Abu-Lughod, Janet (1980). Rabat: Urban Apartheid in Morocco. Princeton University Press.

- Abu-Lughod, Janet (1875). "Moroccan Cities: Apartheid and the Serendipity of Conservation". In Abu-Lughod, Ibrahim (ed.). African Themes: Northwestern University Studies in Honor of Gwendolen M. Carter. Northwestern University Press. pp. 77–111.

- Aouchar, Amina (2005). Fès, Meknès. Flammarion. pp. 192–194.

- Wyrtzen, Jonathan (2016). Making Morocco: Colonial Intervention and the Politics of Identity. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501704246. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- Hart, David M. (1997). "The Berber Dahir of 1930 in colonial Morocco: then and now (1930-1996)". The Journal of North African Studies. 2 (2): 11–33. doi:10.1080/13629389708718294.

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987). A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521337674.

- Aouchar, Amina (2005). Fès, Meknès. Flammarion.

- Lulat, Y. G.-M.: A History Of African Higher Education From Antiquity To The Present: A Critical Synthesis, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005, ISBN 978-0-313-32061-3, pp. 154–157

- "Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University". Times Higher Education (THE). 2020-09-18. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "Medina of Fez". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- Reuters (1990-12-17). "33 Dead in 2-Day Riot in Morocco Fed by Frustration Over Economy (Published 1990)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-01-10.

- "5 Die, 127 Hurt as Worst Riots in 7 Years Sweep Morocco City". Los Angeles Times. 1990-12-16. Retrieved 2021-01-10.

- "La magnifique rénovation des 27 monuments de Fès – Conseil Régional du Tourisme (CRT) de Fès" (in French). Retrieved 2021-01-10.

- "Facelift helps Morocco's Old City of Fez lure tourists |". AW. Retrieved 2021-01-10.

- "Revitalization of the Fez River: A Reclaimed Public Space | Smart Cities Dive". www.smartcitiesdive.com. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- "Aziza Chaouni presents a 2014 TED Talk on her efforts to uncover the Fez River in Morocco". Daniels. 2014-03-20. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- The Rough Guide to Morocco (12th ed.). Rough Guides. 2019.

- Aouchar, Amina (2005). Fès, Meknès. Flammarion. p. 123.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-11-18. Retrieved 2014-09-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Weather history for Fez, Figuig, Morocco : Fez average weather by month". Meoweather.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- "Climatological Information for Fez, Morocco". Hong Kong Observatory. 15 August 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- "Fes, Morocco - Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- "The normals data and climate variable descriptions are presented in these tables as provided by the WMO Member country" (TXT). Ftp.atdd.noaa.gov. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "POPULATION LÉGALE DES RÉGIONS, PROVINCES, PRÉFECTURES, MUNICIPALITÉS, ARRONDISSEMENTS ET COMMUNES DU ROYAUME D'APRÈS LES RÉSULTATS DU RGPH 2014 (12 Régions)". Haut-Commissariat au Plan. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- Le Tourneau, Roger; Paye, L. (1935). "La corporation des tanneurs et l'industrie de la tannerie à Fès". Hespéris. 21: 167–240.

- University, Africa EENI Global Business School &. "Business in Fez, Othman Benjelloun (Morocco)". Africa EENI Global Business School & University. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- Berriane, Johara (2015). "Pilgrimage, Spiritual Tourism and the Shaping of Transnational 'Imagined Communities': the Case of the Tidjani Ziyara to Fez". International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage. 3 (2).

- "Fez-Meknes". Oxford Business Group. 2019-03-13. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- Gaudio, Attilio (1982). Fès: Joyau de la civilisation islamique. Paris: Les Presses de l'Unesco: Nouvelles Éditions Latines. ISBN 2723301591.

- 170. UNESCO. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Jami' al-Qarawiyyin. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Jami' al-Andalusiyyin. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Terrasse, Henri (1964). "La mosquée almohade de Bou Jeloud à Fès". Al-Andalus. 29 (2): 355–363.

- Abu al-Hassan Mosque. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Fez. Archnet. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- Rasif Mosque. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Gilson Miller, Susan; Petruccioli, Attilio; Bertagnin, Mauro (2001). "Inscribing Minority Space in the Islamic City: The Jewish Quarter of Fez (1438-1912)". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 60 (3): 310–327. doi:10.2307/991758. JSTOR 991758.

- "Fez, Morocco Jewish History Tour". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2020-04-08.

- Jewish in Morocco

- Audurier Cros, Alix. "L'Eglise St François d'Assise, FES, Maroc" (PDF).

- "Diocèse de Rabat". www.dioceserabat.org. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- "Église de Saint François d'Assise". GCatholic. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- "Oldest higher-learning institution, oldest university". Guinnessworldrecords.com. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Penell, C.R. Morocco: From Empire to Independence; Oneworld Publications, Oct 1, 2013. pp.66-67.

- Shiratin Madrasa. Archnet. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- Fortifications of Fès. Archnet. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Meredith, Martin. (2014). Fortunes of Africa: A 5,000 Year History of Wealth, Greed and Endeavour. Simon and Schuster.

- Hakluyt Society, (1896). Works Issued by the Hakluyt Society, p.592.

- نفائس فاس العتيقة : بناء 13 قصبة لأغراض عسكرية. Assabah. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- Qasbah Dar Debibagh. 'Archnet Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- البرج الشمالي. Museum with no Frontiers. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Chouara Tannery. Archnet. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Why You Need to Visit Fez in 20 Photos. Bloomberg. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Aziza Chaouni: Hybrid Urban Sutures: Filling in the Gaps in the Medina of Fez." Archit 96 no. 1 (2007): 58-63.

- "Fes". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. 3 Mar. 2007

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987). A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521337674.

- Sidi Ahmed al-Tijani Zawiya. Archnet. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Fès et sainteté, de la fondation à l'avènement du Protectorat (808-1912): Hagiographie, tradition spirituelle et héritage prophétique dans la ville de Mawlāy Idrīs. Rabat: Centre Jacques-Berque. 2014. ISBN 9791092046175.

- "Jnane Sbile or Bab Bou Jeloud garden in Fez". Morocco.FalkTime. 2018-07-09. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- Parker, Richard (1981). A practical guide to Islamic Monuments in Morocco. Charlottesville, VA: The Baraka Press.

- Funduq al-Najjariyyin. Archnet. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- "Fès: Les fondouks de la médina restaurés et labellisés". L'Economiste (in French). 2016-04-08. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- "Qantara - The al-Shammā'īn Funduq". www.qantara-med.org. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- Sibley, Magda; Jackson, Iain (2012). "The architecture of Islamic public baths of North Africa and the Middle East: an analysis of their internal spatial configurations". Architectural Research Quarterly. 16 (2): 155–170. doi:10.1017/S1359135512000462.

- Sibley, Magda (2006). "The Historic Hammāms of Damascus and Fez: Lessons of Sustainability and Future Developments". The 23rd Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture (Geneva, Switzerland, 6–8 September 2006).

- Raftani, Kamal; Radoine, Hassan (2008). "The Architecture of the Hammams of Fez, Morocco". Archnet-IJAR. 2 (3): 56–68.

- Secret, Edm. (1942). "Les hammams de Fes" (PDF). Bulletin de l'Institut d'Hygiène du Maroc. 2: 61–78.

- Terrasse, Henri (1950). "Trois Bains Mérinides du Maroc". Mélanges offerts à William Marçais par l'Institut d'études islamiques de l'Université de Paris. Paris: Éditions G.-P. Maisonneuve.

- "Alami House". Archnet. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- "Histoire du Maroc : Palais Jamai, Patrimoine universel. – Cabinet Consulting Expertise International" (in French). Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- "Palais Glaoui | Fez, Morocco Attractions". www.lonelyplanet.com. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- Mezzine, Mohamed. "Batha Palace". Discover Islamic Art, Museum With No Frontiers. Retrieved March 2020. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Guinness World Records, Oldest University

- UNESCO, World Heritage Listing for Medina of Fez.

- Larbi Arbaoui, Al Karaouin of Fez: The Oldest University in the World, Morocco World News, 2 October 2012.

- "Présentation institutionnelle". Portail USMBA (in French). Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "l'USMBA en chiffres". Portail USMBA (in French). Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "UEMF - Tout sur Université Euromed de Fès". Etudiant.ma. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "L'UEMF | UEMF". www.ueuromed.org. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "Daoudi autorise une première université privée à Fès". L'Economiste (in French). 2013-12-26. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "Fès se dote d'une école d'ingénieurs". L'Economiste (in French). 2006-07-20. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "Université Privée de Fès – 1ère Université Privée à Fès Reconnue par l'Etat" (in French). Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "Tourism in Fez-Meknes grows on the strength of religious and wellness visitors". Oxford Business Group. 2019-03-13. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "::.. Oncf ..::". Oncf.ma. Archived from the original on 2009-02-28. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- "Transportation in Fez, Morocco". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- Planet, Lonely. "Bus in Fez, Morocco". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "Twin Towns". fescity.com. Fes City. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- "Profile of Sister Cities". gochengdu.cn. Go Chengdu. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- "Cidades Geminadas". cm-coimbra.pt (in Portuguese). Coimbra. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- "Las 12 hermanas de Córdoba". diariocordoba.com (in Spanish). Diario Córdoba. 2020-02-10. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- "العلاقات التي تربط مدينة أريحا بالمدن الأجنبية". jericho-city.ps (in Arabic). Jericho. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- "Sister Cities". wuxinews.com.cn. Wuxi News. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- "Sister cities". xa.gov.cn. Xi'an. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

Further reading

- Le Tourneau, Roger (1974) [1961]. Fez in the Age of the Marinides. Translated by Besse Clement. Oklahoma University. ISBN 0-8061-1198-4.

- Vigo, Julian (2006). "The Renovation of Fes' medina qdima and the (re)Creation of the Traditional". Writing the City, Transforming the City. New Delhi: Katha. pp. 44–58.

- "Place Lalla Yeddouna A Neighborhood in the Medina of Fez, Morocco: International open project competition in two phases". Announced in September 2010 in collaboration with the Union International des Architectes (UIA) and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), to renew the area and upgrade the living and working standards of the artisans in the medina. The approach of the project is probably one of the most ambitious for an Arab medina and therefore of exemplary character. The open international project was won by the London-based architecture practice Mossessian & Partners.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fes. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Fez. |