Crepuscular animal

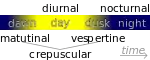

A crepuscular animal is one that is active primarily during the twilight period.[1] This is distinguished from diurnal and nocturnal behavior, where an animal is active during the hours of daylight and of darkness, respectively. Some crepuscular animals may also be active by moonlight or during an overcast day. Matutinal animals are active only before sunrise, and vespertine only after sunset.

| Look up crepuscular in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

A number of factors impact the time of day an animal is active. Predators hunt when their prey is available, and prey try to avoid the times when their principal predators are at large. The temperature at midday may be too high or at night too low.[2] Some creatures may adjust their activities depending on local competition.

Etymology and usage

The word crepuscular derives from the Latin crepusculum ("twilight").[3] Its sense accordingly differs from diurnal and nocturnal behavior, which respectively peak during hours of daylight and darkness. The distinction is not absolute however, because crepuscular animals may also be active on a bright moonlit night or on a dull day. Some animals casually described as nocturnal are in fact crepuscular.[2]

Special classes of crepuscular behaviour include matutinal (or "matinal", animals active only in the dawn) and vespertine (only in the dusk). Those active during both times are said to have a bimodal activity pattern.

Adaptive relevance

The various patterns of activity are thought to be mainly antipredator adaptations, though some could equally well be predatory adaptations. Many predators forage most intensively at night, whereas others are active at midday and see best in full sun. Thus, the crepuscular habit may both reduce predation pressure, thereby increasing the crepuscular populations, and in consequence offer better foraging opportunities to predators that increasingly focus their attention on crepuscular prey until a new balance is struck. Such shifting states of balance are often found in ecology.

Some predatory species adjust their habits in response to competition from other predators. For example, the subspecies of short-eared owl that lives on the Galápagos Islands is normally active during the day, but on islands like Santa Cruz that are home to the Galapagos hawk, the owl is crepuscular.[4][5]

Apart from the relevance to predation, crepuscular activity in hot regions also may be the most effective way of avoiding heat stress while capitalizing on available light.

Occurrence of crepuscular behaviour

_Zoo_Itatiba.jpg.webp)

Many familiar mammal species are crepuscular, including some bats,[2] hamsters, housecats, stray dogs,[6] rabbits,[2] ferrets,[7] and rats.[8] Other crepuscular mammals include jaguars, ocelots, bobcats, servals, strepsirrhines, red pandas, bears,[9] deer,[2][10] moose, sitatunga, capybaras, chinchillas, the common mouse, skunks, squirrels, Australian wombats, wallabies, quolls, possums[2] and marsupial gliders, tenrecs, and spotted hyenas.

Snakes and lizards, especially those in desert environments, may be crepuscular.[2]

Crepuscular birds include the common nighthawk, barn owl,[11] owlet-nightjar, chimney swift, American woodcock, spotted crake, and white-breasted waterhen.[12]

Many moths, beetles, flies, and other insects are crepuscular and vespertine.

See also

References

- "Glossary". North American Mammals. Smithsonian – National Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- "Crepuscular". Macmillan Science Library: Animal Sciences. Macmillan Reference USA. 2001–2006. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- Winn, Philip (2001). Dictionary of Biological Psychology. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-13606-7.

- Frederick, Prince (2006-04-15). "Night herons in the day!". Metro Plus Chennai. The Hindu. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- Merck, John. "The community of terrestrial animals". Field Studies II: The Natural History of the Galápagos Islands. University of Maryland Department of Geology. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- Beck, Alan M. (2002). The Ecology of Stray Dogs: A Study of Free-Ranging Urban Animals – Alan M. Beck – Google Books. ISBN 9781557532459. Retrieved 2012-04-13.

- Williams, David L. (2012). Ophthalmology of Exotic Pets. John Wiley & Sons. p. 73. ISBN 9781444361254. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- Williams, David L. (2012). Ophthalmology of Exotic Pets. John Wiley & Sons. p. 88. ISBN 9781444361254. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- Schaul, Jordan Carlton (April 6, 2011). "The Kodiak Cubs Meet Their Neighbors, The American Black Bears". National Geographic Voices. National Geographic Society. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- "White-Tailed Deer". Animals. National Geographic Partners, LLC. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- Audubon, John J. (1827–1838). "Plate 171: Barn Owl". Birds of America.

- Boyes, Steve (October 7, 2012). "Top 25 Wild Bird Photographs of the Week #23". National Geographic Voices. National Geographic Society. Retrieved July 15, 2017.