Décollement

Décollement (from French décoller 'to detach from') is a gliding plane between two rock masses, also known as a basal detachment fault. Décollements are a deformational structure, resulting in independent styles of deformation in the rocks above and below the fault. They are associated with both compressional settings (involving folding and overthrusting[3]) and extensional settings.

Origin

The term was first used by geologists studying the structure of the Swiss Jura Mountains,[4] coined in 1907 by A. Buxtorf, who released a paper that theorized that the Jura is the frontal part of a décollement at the base of a nappe, rooted in the faraway Swiss Alps.[5][6] Marcel Alexandre Bertrand published a paper in 1884 that dealt with Alpine nappism. Thin-skinned tectonics was implied in that paper but the actual term was not used until Buxtorf's 1907 publication.[4][5]

Formation

Décollements are caused by surface forces, which 'push' at converging plate boundaries, facilitated by body forces[7] (gravity sliding). Mechanically weak layers in strata allow the development of stepped thrusts (either over- or underthrusts),[8] which originate at subduction zones and emerge deep in the foreland. Rock bodies with differing lithologies have different characteristics of tectonic deformation. They can behave in a brittle manner above the décollement surface, with intense ductile deformation below the décollement surface.[9] Décollement horizons may be at depths as great as 10 km[10] and form due to high compressibility between differing rock bodies or along planes of high pore pressures.[11]

Typically, the basal detachment of the foreland part of a fold-thrust belt lies in a weak shale or evaporite at or near the basement.[1] Rocks above the décollement are allochthonous, rocks below are autochthonous.[1] If material is transported along a décollement greater than 2 km, it may be considered a nappe.[5] The faulting and folding that occurs with a regional basal detachment may be referred to as "thin-skinned tectonics",[1] but décollements occur in 'thick-skinned' deformational regimes as well.[12]

Compressional setting

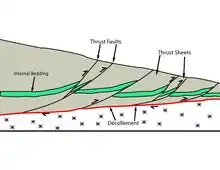

In a fold-thrust belt, the décollement is the lowest detachment[1] (see Fig 1.) and forms in the foreland basin of a subduction zone.[1] A fold-thrust belt may contain other detachments above the décollement—an imbricate fan of thrust faults and duplexes as well as other detachment horizons. In compressional settings, the layer directly above the décollement will develop more intense deformation than other layers, and weaker deformation below the décollement.[13]

Effect of friction

Décollements are responsible for duplex formation, the geometry of which greatly influences the dynamics of the thrust wedge.[14] The amount of friction along the décollement affects the shape of the wedge; a low-angle slope reflects a low-friction décollement, whereas a higher-angle slope reflects a higher-friction basal detachment.[2]

Types of folding

Two different types of folding may occur at a décollement. Concentric folding is identified by uniform bed thickness throughout the fold, and is necessarily accompanied by detachment or a décollement as part of the deformation that occurs with a thrust fault.[15] Disharmonic folding does not have uniform bed thickness throughout the fold.[16]

Extensional setting

Décollements in extensional settings are accompanied by tectonic denudation and high cooling rates.[5] They can form by several methods:

- The megalandslide model predicts extension with normal faults near the original fault source and shortening further away from the source.[18]

- The in situ model predicts numerous normal faults overlying one large décollement.[18]

- The rooted, low angle normal fault model predicts that the décollement is created when two thin sheets of rock decouple at depth. Near the thickest part of the upper plate, extensional faulting may be negligible or absent, but as the upper plate thins, it loses its ability to remain coherent and may behave as a thin-skinned extensional terrane.[18]

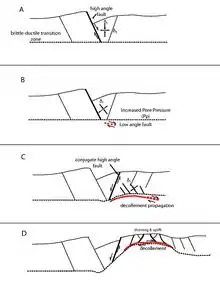

- Décollements can form from high angle normal faults.[9][18] Uplift in a second stage of extension allows the exhumation of a metamorphic core complex (see Fig. 2). A half graben forms, but stress orientation is not perturbed due to high fault friction. Next, elevated pore pressure (Pp) leads to low effective friction that forces σ1 to be parallel to the fault in the footwall. A low-angle fault forms and is ready to act as décollement. Then, the upper crust is thinned above the décollement by normal faulting. New high-angle faults control the propagation of the décollement and help crustal exhumation. Finally, major and rapid horizontal extension lifts the terrain isostatically and isothermally. A décollement develops as an antiform that migrates toward shallower depths.[9]

Examples

Jura Décollement

Located in the Jura Mountains, north of the Alps, it was originally thought to be a folded décollement nappe.[5][6] The thin-skinned nappe was sheared off on 1000 meter-thick deposits of Triassic evaporites.[5][19][20] The frontal basal detachment of the Jura fold-and-thrust belt forms the most external limit of the Alpine orogenic wedge with the youngest fold-and-thrust activity.[21] The Mesozoic and Cenozoic cover of the fold-and-thrust belt and the adjacent Molasse Basin have been deformed over the weak basal décollement and displaced by some 20 km and more toward the northwest.[19]

Appalachian-Ouachita Décollement

The Appalachian-Ouachita orogen along the southeastern margin of the North American craton includes a late Paleozoic fold-thrust belt with a thin-skinned flat-and-ramp geometry, related to lateral and vertical variations in rock lithologies. The décollement surface varies along and across strike. Promontories and embayments in the late Precambrian-early Paleozoic rifted margin are preserved in the décollement geometry.[22]

References

- Van Der Pluijm, Ben A. (2004). Earth Structure. New York, NY: W.W. Norton. p. 457. ISBN 978-0-393-92467-1.

- Malavieille, Jacques (2010). "Impact of erosion, sedimentation, and structural heritage on the structure and kinematics of orogenic wedges: Analog models and case studies". GSA Today: 4. doi:10.1130/GSATG48A.1.

- Bates, Robert L.; Julia A. Jackson (1984). Dictionary of Geological Terms (Third ed.). New York: Anchor Books. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-385-18101-3.

- Bertrand, M. (1884). "Rapports de structure des Alpes de Glaris et du bassin houiller du Nord". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 3rd series. 12: 318–330.

- H.P. Laubscher, Basel (1988). "Décollement in the Alpine system: an overview". Geologische Rundschau. 77 (1): 1–9. Bibcode:1988GeoRu..77....1L. doi:10.1007/BF01848672.

- Buxtorf, A. (1907). "Zur Tektonik des Kettenjura". Berichte über die Versammlungen des Oberrheinischen Geologischen Verein: 29–38.

- Hubbert, M. K.; Rubey, W. W. (1959). "Role of fluid pressure in mechanics of overthrust faulting, 1. Mechanics of fluid-filled porous solids and its application to overthrust faulting". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 70 (2): 115–166. Bibcode:1959GSAB...70..115K. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1959)70[115:ROFPIM]2.0.CO;2.

- Laubscher, H. P. (1987). Décollement. Encyclopedia of Earth Science. p. 187. doi:10.1007/3-540-31080-0_27. ISBN 978-0-442-28125-0.

- Chery, Jean (2001). "Core complex mechanics: From the Gulf of Corinth to the Snake Range". Geology. 29 (5): 439–442. Bibcode:2001Geo....29..439C. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0439:CCMFTG>2.0.CO;2.

- McBride, John H.; Pugin, J.M.; Hatcher Jr., D. (2007). Scale independence of décollement thrusting. Geological Society of America Memoirs. 200. pp. 109–126. doi:10.1130/2007.1200(07). ISBN 978-0-8137-1200-0.

- Ramsay, J, 1967, Folding and Fracturing of Rocks, McGraw-Hill ISBN 978-0-07-051170-5

- Bigi, Sabina; Doglioni, Carlo (2002). "Thrust vs Normal Fault Decollements in The Central Appennines" (PDF). Bollettino della Società Geologica Italiana. 1: 161–166.

- LiangJie, Tang; Yang KeMing; Jin WenZheng; LÜ ZhiZhou; Yu YiXin (2008). "Multi-level decollement zones and detachment deformation of Longmenshan thrust belt, Sichuan Basin, southwest China". Science in China Series D: Earth Sciences. 51 (suppl. 2): 32–43. doi:10.1007/s11430-008-6014-9.

- Konstantinovskaya, E.; J. Malavieille (April 20, 2011). "Thrust wedges with décollement :levels and syntectonic erosion: A view from analog models". Tectonophysics. 502 (3–4): 336–350. Bibcode:2011Tectp.502..336K. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2011.01.020.

- Dahlstrom, C.D.A. (1969). "The upper detachment in concentric folding". Bulletin of Canadian Petroleum Geology. 17 (3): 326–347.

- Billings, M.P. (1954). Structural Geology (2nd ed.). New York: Prentice-Hall. p. 514.

- Warren, John K. (2006). "Salt tectonics". Evaporites: Sediments, Resources and Hydrocarbons. pp. 375–415. doi:10.1007/3-540-32344-9_6. ISBN 978-3-540-26011-0.

- Wernicke, Brian (25 June 1981). "Low-angle normal faults in the Basin and Range Province: nappe tectonics in an extending orogen". Nature. 291 (5817): 645–646. Bibcode:1981Natur.291..645W. doi:10.1038/291645a0.

- Sommaruga, A. (1998). "Décollement tectonics in the Jura foreland fold-and-thrust belt". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 16 (2): 111–134. doi:10.1016/S0264-8172(98)00068-3.

- Laubscher, Hans (2008). "The Grenchenberg conundrum in the Swiss Jura: a case for the centenary of the thin-skin décollement nappe model (Buxtorf 1907)". Swiss Journal of Geosciences. 101: 41–60. doi:10.1007/s00015-008-1248-2.

- Mosar, Jon (1999). "Present-day and future tectonic underplating in the western Swiss" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 39 (3): 143. Bibcode:1999E&PSL.173..143M. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(99)00238-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-16.

- Thomas, William A. (1988). "Stratigraphic framework of the geometry of the basal decollement of the Appalachian-Ouachita fold-thrust belt". Geologische Rundschau. 77 (1): 183–190. Bibcode:1988GeoRu..77..183T. doi:10.1007/BF01848683.