DFA minimization

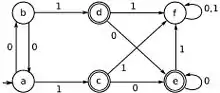

In automata theory (a branch of theoretical computer science), DFA minimization is the task of transforming a given deterministic finite automaton (DFA) into an equivalent DFA that has a minimum number of states. Here, two DFAs are called equivalent if they recognize the same regular language. Several different algorithms accomplishing this task are known and described in standard textbooks on automata theory.[1]

Minimal DFA

For each regular language, there also exists a minimal automaton that accepts it, that is, a DFA with a minimum number of states and this DFA is unique (except that states can be given different names).[2][3] The minimal DFA ensures minimal computational cost for tasks such as pattern matching.

There are two classes of states that can be removed or merged from the original DFA without affecting the language it accepts to minimize it.

- Unreachable states are the states that are not reachable from the initial state of the DFA, for any input string.

- Nondistinguishable states are those that cannot be distinguished from one another for any input string.

DFA minimization is usually done in three steps, corresponding to the removal or merger of the relevant states. Since the elimination of nondistinguishable states is computationally the most expensive one, it is usually done as the last step.

Unreachable states

The state p of a deterministic finite automaton M=(Q, Σ, δ, q0, F) is unreachable if no string w in Σ* exists for which p=δ*(q0, w). In this definition, Q is the set of states, Σ is the set of input symbols, δ is the transition function (mapping a state and an input symbol to a set of states), δ*is its extension to strings, q0 is the initial state, and F is the set of accepting (aka final) states. Reachable states can be obtained with the following algorithm:

let reachable_states := {q0};

let new_states := {q0};

do {

temp := the empty set;

for each q in new_states do

for each c in Σ do

temp := temp ∪ {p such that p = δ(q,c)};

end;

end;

new_states := temp \ reachable_states;

reachable_states := reachable_states ∪ new_states;

} while (new_states ≠ the empty set);

unreachable_states := Q \ reachable_states;

Unreachable states can be removed from the DFA without affecting the language that it accepts.

Nondistinguishable states

Hopcroft's algorithm

One algorithm for merging the nondistinguishable states of a DFA, due to Hopcroft (1971), is based on partition refinement, partitioning the DFA states into groups by their behavior. These groups represent equivalence classes of the Myhill–Nerode equivalence relation, whereby every two states of the same partition are equivalent if they have the same behavior for all the input sequences. That is, for every two states p1 and p2 that belong to the same equivalence class within the partition P, and every input word w, the transitions determined by w should always take states p1 and p2 to equal states, states that both accept, or states that both reject. It should not be possible for w to take p1 to an accepting state and p2 to a rejecting state or vice versa.

The following pseudocode describes the algorithm:

P := {F, Q \ F};

W := {F, Q \ F};

while (W is not empty) do

choose and remove a set A from W

for each c in Σ do

let X be the set of states for which a transition on c leads to a state in A

for each set Y in P for which X ∩ Y is nonempty and Y \ X is nonempty do

replace Y in P by the two sets X ∩ Y and Y \ X

if Y is in W

replace Y in W by the same two sets

else

if |X ∩ Y| <= |Y \ X|

add X ∩ Y to W

else

add Y \ X to W

end;

end;

end;

The algorithm starts with a partition that is too coarse: every pair of states that are equivalent according to the Myhill–Nerode relation belong to the same set in the partition, but pairs that are inequivalent might also belong to the same set. It gradually refines the partition into a larger number of smaller sets, at each step splitting sets of states into pairs of subsets that are necessarily inequivalent. The initial partition is a separation of the states into two subsets of states that clearly do not have the same behavior as each other: the accepting states and the rejecting states. The algorithm then repeatedly chooses a set A from the current partition and an input symbol c, and splits each of the sets of the partition into two (possibly empty) subsets: the subset of states that lead to A on input symbol c, and the subset of states that do not lead to A. Since A is already known to have different behavior than the other sets of the partition, the subsets that lead to A also have different behavior than the subsets that do not lead to A. When no more splits of this type can be found, the algorithm terminates.

Lemma. Given a fixed character c and an equivalence class Y that splits into equivalence classes B and C, only one of B or C is necessary to refine the whole partition.[4]

Example: Suppose we have an equivalence class Y that splits into equivalence classes B and C. Suppose we also have classes D, E, and F; D and E have states with transitions into B on character c, while F has transitions into C on character c. By the Lemma, we can choose either B or C as the distinguisher, let's say B. Then the states of D and E are split by their transitions into B. But F, which doesn't point into B, simply doesn't split during the current iteration of the algorithm; it will be refined by other distinguisher(s).

Observation. All of B or C is necessary to split referring classes like D, E, and F correctly-- subsets won't do.

The purpose of the outermost if statement (if Y is in W) is to patch up W, the set of distinguishers. We see in the previous statement in the algorithm that Y has just been split. If Y is in W, it has just become obsolete as a means to split classes in future iterations. So Y must be replaced by both splits because of the Observation above. If Y is not in W, however, only one of the two splits, not both, needs to be added to W because of the Lemma above. Choosing the smaller of the two splits guarantees that the new addition to W is no more than half the size of Y; this is the core of the Hopcroft algorithm: how it gets its speed, as explained in the next paragraph.

The worst case running time of this algorithm is O(ns log n), where n is the number of states and s is the size of the alphabet. This bound follows from the fact that, for each of the ns transitions of the automaton, the sets drawn from Q that contain the target state of the transition have sizes that decrease relative to each other by a factor of two or more, so each transition participates in O(log n) of the splitting steps in the algorithm. The partition refinement data structure allows each splitting step to be performed in time proportional to the number of transitions that participate in it.[5] This remains the most efficient algorithm known for solving the problem, and for certain distributions of inputs its average-case complexity is even better, O(n log log n).[6]

Once Hopcroft's algorithm has been used to group the states of the input DFA into equivalence classes, the minimum DFA can be constructed by forming one state for each equivalence class. If S is a set of states in P, s is a state in S, and c is an input character, then the transition in the minimum DFA from the state for S, on input c, goes to the set containing the state that the input automaton would go to from state s on input c. The initial state of the minimum DFA is the one containing the initial state of the input DFA, and the accepting states of the minimum DFA are the ones whose members are accepting states of the input DFA.

Moore's algorithm

Moore's algorithm for DFA minimization is due to Edward F. Moore (1956). Like Hopcroft's algorithm, it maintains a partition that starts off separating the accepting from the rejecting states, and repeatedly refines the partition until no more refinements can be made. At each step, it replaces the current partition with the coarsest common refinement of s + 1 partitions, one of which is the current one and the others are the preimages of the current partition under the transition functions for each of the input symbols. The algorithm terminates when this replacement does not change the current partition. Its worst-case time complexity is O(n2s): each step of the algorithm may be performed in time O(ns) using a variant of radix sort to reorder the states so that states in the same set of the new partition are consecutive in the ordering, and there are at most n steps since each one but the last increases the number of sets in the partition. The instances of the DFA minimization problem that cause the worst-case behavior are the same as for Hopcroft's algorithm. The number of steps that the algorithm performs can be much smaller than n, so on average (for constant s) its performance is O(n log n) or even O(n log log n) depending on the random distribution on automata chosen to model the algorithm's average-case behavior.[6][7]

Brzozowski's algorithm

Reversing the transitions of a non-deterministic finite automaton (NFA) and switching initial and final states[note 1] produces an NFA for the reversal of the original language. Converting this NFA to a DFA using the standard powerset construction (keeping only the reachable states of the converted DFA) leads to a DFA for the same reversed language. As Brzozowski (1963) observed, repeating this reversal and determinization a second time, again keeping only reachable states, produces the minimal DFA for the original language.

The intuition behind the algorithm is this: After we determinize to obtain , we reverse this to obtain . Now has the same language as , but there's one important difference: there are no two states in from which we can accept the same word. This follows from being deterministic, viz. there are no two states in , which we can reach from the initial state through the same word. The determinization of then creates powerstates (sets of states of ), where every two powerstates differ ‒ naturally ‒ in at least one state of . Assume and ; then contributes at least one word[note 2] to the language of [note 3] which couldn't possibly be present in , since this word is unique to (no other state accepts it). We see that this holds for each pair of powerstates, and thus each powerstate is distinguishable from every other powerstate. Therefore, after determinization of , we have a DFA with no indistinguishable or unreachable states; hence, the minimal DFA for the original .

If is already deterministic, then it suffices to trim it,[note 4] reverse it, determinize it, and then reverse it again. This could be thought of as starting with in the process above (assuming it has already been trimmed), since the input FA is already deterministic (but keep in mind it's actually not a reversal). We reverse and determinize to obtain , which is the minimal DFA for the reversal of the language of (since we did only one reversal so far). Now all that's left to do is to reverse to obtain the minimal DFA for the original language.

The worst-case complexity of Brzozowski's algorithm is exponential in the number of states of the input automaton. This holds regardless of whether the input is a NFA or a DFA. In the case of DFA, the exponential explosion can happen during determinization of the reversal of the input automaton;[note 5] in the case of NFA, it can also happen during the initial determinization of the input automaton.[note 6] However, the algorithm frequently performs better than this worst case would suggest.[6]

NFA minimization

While the above procedures work for DFAs, the method of partitioning does not work for non-deterministic finite automata (NFAs).[8] While an exhaustive search may minimize an NFA, there is no polynomial-time algorithm to minimize general NFAs unless P=PSPACE, an unsolved conjecture in computational complexity theory which is widely believed to be false. However, there are methods of NFA minimization that may be more efficient than brute force search.[9]

See also

Notes

- Hopcroft, Motwani & Ullman (2001), Section 4.4.3, "Minimization of DFA's".

- Hopcroft & Ullman (1979), Section 3.4, Theorem 3.10, p.67

- Hopcroft, Motwani & Ullman (2001), Section 4.4.3, "Minimization of DFA's", p. 159, and p. 164 (remark after Theorem 4.26)

- Based on Corollary 10 of Knuutila (2001)

- Hopcroft (1971); Aho, Hopcroft & Ullman (1974)

- Berstel et al. (2010).

- David (2012).

- Hopcroft, Motwani & Ullman (2001), Section 4.4, Figure labeled "Minimizing the States of an NFA", p. 163.

- Kameda & Weiner (1970).

- In case there are several final states in M, we either must allow multiple initial states in the reversal of M; or add an extra state with ε-transitions to all the initial states, and make only this new state initial.

- Recall there are no dead states in M'; thus, at least one word is accepted from each state.

- Language of a state is the set of words accepted from that state.

- Trim = remove unreachable and dead states.

- For instance, the language of binary strings whose nth symbol is a one requires only n + 1 states, but its reversal requires 2n states. Leiss (1981) provides a ternary n-state DFA whose reversal requires 2n states, the maximum possible. For additional examples and the observation of the connection between these examples and the worst-case analysis of Brzozowski's algorithm, see Câmpeanu et al. (2001).

- Exponential explosion will happen at most once, not in both determinizations. That is, the algorithm is at worst exponential, not doubly-exponential.

References

- Aho, Alfred V.; Hopcroft, John E.; Ullman, Jeffrey D. (1974), "4.13 Partitioning", The Design and Analysis of Computer Algorithms, Addison-Wesley, pp. 157–162.

- Berstel, Jean; Boasson, Luc; Carton, Olivier; Fagnot, Isabelle (2010), "Minimization of Automata", Automata: from Mathematics to Applications, European Mathematical Society, arXiv:1010.5318, Bibcode:2010arXiv1010.5318B

- Brzozowski, J. A. (1963), "Canonical regular expressions and minimal state graphs for definite events", Proc. Sympos. Math. Theory of Automata (New York, 1962), Polytechnic Press of Polytechnic Inst. of Brooklyn, Brooklyn, N.Y., pp. 529–561, MR 0175719.

- Câmpeanu, Cezar; Culik, Karel, II; Salomaa, Kai; Yu, Sheng (2001), "State Complexity of Basic Operations on Finite Languages", 4th International Workshop on Automata Implementation (WIA '99), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2214, Springer-Verlag, pp. 60–70, doi:10.1007/3-540-45526-4_6, ISBN 978-3-540-42812-1.

- David, Julien (2012), "Average complexity of Moore's and Hopcroft's algorithms", Theoretical Computer Science, 417: 50–65, doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2011.10.011.

- Hopcroft, John (1971), "An n log n algorithm for minimizing states in a finite automaton", Theory of machines and computations (Proc. Internat. Sympos., Technion, Haifa, 1971), New York: Academic Press, pp. 189–196, MR 0403320. See also preliminary version, Technical Report STAN-CS-71-190, Stanford University, Computer Science Department, January 1971.

- Hopcroft, John E.; Ullman, Jeffrey D. (1979), Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation, Reading/MA: Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-0-201-02988-8

- Hopcroft, John E.; Motwani, Rajeev; Ullman, Jeffrey D. (2001), Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation (2nd ed.), Addison-Wesley.

- Kameda, Tsunehiko; Weiner, Peter (1970), "On the state minimization of nondeterministic finite automata", IEEE Transactions on Computers, 100 (7): 617–627, doi:10.1109/T-C.1970.222994.

- Knuutila, Timo (2001), "Re-describing an algorithm by Hopcroft", Theoretical Computer Science, 250 (1–2): 333–363, doi:10.1016/S0304-3975(99)00150-4, MR 1795249.

- Leiss, Ernst (1981), "Succinct representation of regular languages by Boolean automata", Theoretical Computer Science, 13 (3): 323–330, doi:10.1016/S0304-3975(81)80005-9, MR 0603263.

- Leiss, Ernst (1985), "Succinct representation of regular languages by Boolean automata II", Theoretical Computer Science, 38: 133–136, doi:10.1016/0304-3975(85)90215-4

- Moore, Edward F. (1956), "Gedanken-experiments on sequential machines", Automata studies, Annals of mathematics studies, no. 34, Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press, pp. 129–153, MR 0078059.

- Sakarovitch, Jacques (2009), Elements of automata theory, Translated from French by Reuben Thomas, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-84425-3, Zbl 1188.68177