Dengbêj

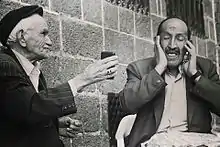

Dengbêj is a Kurdish music genre and/or a singer of the music genre Dengbêj. Dengbêjs are singing storytellers. There have been many terms to describe Dengbêjs throughout history, but today Dengbêj is the best known, and also several singing storytellers use Dengbêj as part of their (artistic) name.[1] Dengbêjs are viewed as a way to transmit the traditions of their Kurdish ancestors in times as it was not possible to publish in Kurdish or about Kurdish history. Since there don't exist many documents about certain Kurdish events, today there exist attempts to analyze them through the songs of the Dengbêjs.[2] They sing about the Kurdish geography,[3] history, recent events, but also lullabies and love songs[4] The Kilam is a speciality of the Dengbêjs, where they just let the out what moves them, and do not so much watch to make a pause after the end of a phrase.[5] If they sing in the style of a stran, the song is more melodic and rhythmic, popular and love songs sung at weddings are sung in stran style.[5] They sing mostly without instruments accompanying them.[6] Traditionally Dengbêjs need to first learn the Dengbêj songs from the ancestors before performing their own songs.[7] Well known Dengbêjs are Karapetê Xaço, Evdalê Zeynikî and[8] Sakîro.[9] In the 1980s the Dengbêjs were persecuted for singing in Kurdish as it was forbidden in Turkey to sing in Kurdish language.[10] In 1991, Turgut Özal achieved that the use of the Kurdish language became legal except for broadcast, publications, education and in politics.[11] Therefore, the Dengbêjs were again able to perform with more freedom. From 1994 onwards the Dengbêjs were supported by Kurdish politicians to attend festivals and TV shows out of Turkey and from the 2000s also inside Turkey. Therefore, the Dengbêj music became politicized and as a sign of Kurdishness, which confronted the Turkish nationalism.[12]

In 2003 a first Mala Dengbêjan (Dengbêj House in Kurdish) was in inaugurated in Van.[13] In May 2007 the Municipality of Diyarbakır supported the establishment of the Mala Dengbêjan in Diyarbakır.[14] In several other cities, Dengbêj houses were founded as well.[13]

References

- Kardaş, Canser (2019-02-05). Ulaş, Özdemir; Hamelink, Wendelmoet; Greve, Martin (eds.). Diversity and Contact among Singer-Poet Traditions in Eastern Anatolia. Ergon Verlag. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-3-95650-481-5.

- Kardas, Canser (2019-02-05). Ulas, Özdemir; Hamelink, Wendelmoet; Greve, Martin (eds.). Diversity and Contact among Singer-Poet Traditions in Eastern Anatolia. Ergon Verlag. p. 39. ISBN 978-3-95650-481-5.

- Wendelmoet Hamelink, (2016), p. 110-112

- Hamelink, Wendelmoet (2016). The Sung Home. Narrative, Morality, and the Kurdish Nation. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 381–395. ISBN 978-90-04-31482-5.

- Wendelmoet Hamelink, (2016), p. 58

- Özdemir, Ulaş; Hamelink, Wendelmoet; Greve, Martin (2019-02-05). Diversity and Contact among Singer-Poet Traditions in Eastern Anatolia. Ergon Verlag. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-95650-481-5.

- Hamelink, Özdemir, (2019), p. 42

- Wendelmoet Hamelink, (2016), p. 209

- Wendelmoet Hamelink, (2016), p. 210

- Wendelmoet Hamelink, (2016), pp. 211-212

- Romano, David; Romano, Thomas G. Strong Professor of Middle East Politics David (2006). The Kurdish Nationalist Movement: Opportunity, Mobilization and Identity. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 55. ISBN 9780521850414.

- Wendelmoet Hamelink, (2016), pp. 287-288

- Wendelmoet Hamelink, (2016), p. 307

- Greve, Martin (2018-01-12). Makamsiz: Individualization of Traditional Music on the Eve of Kemalist Turkey. Ergon Verlag. p. 156. ISBN 978-3-95650-371-9.