Denishawn school

The Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts, founded in 1915 by Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn in Los Angeles, California, helped many perfect their dancing talents and became the first dance academy in the United States to produce a professional dance company.[1] Some of the school's more notable pupils include Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Lillian Powell, Charles Weidman, Jack Cole, and silent film star Louise Brooks. The school was especially renowned for its influence on ballet and experimental modern dance. In time, Denishawn teachings reached another school location as well - Studio 61 at the Carnegie Hall Studios.

Beginnings

Initially solo artists, Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn began collaborating on work in 1914. At the time, St. Denis was preparing for a tour of the southeastern region of the United States, and needed a male partner to help present new ballroom dances. Shawn, who had admired St. Denis since seeing her perform in 1911, auditioned for and was awarded the role. The resulting tour featured the partnered pieces along with individual works from St. Denis and Shawn respectively.

Eventually, the working relationship between Shawn and St. Denis turned romantic. The two artists fell in love and, lovers living together being considered unorthodox at this point in history, were married on August 13, 1914.[2] Denis, reticent about marriage, had the word "obey" deleted from their wedding vows and declined to wear a wedding ring.[3] Their "honeymoon" consisted of a second joint tour - accompanied by a small company of dancers - from Saratoga, New York to San Francisco, California. A new collection of dances, including more ballroom variations, St. Denis' solos and Shawn's famous Dagger Dance, was showcased. For promotional purposes, the dancing group was referred to as the St. Denis-Shawn Company. Meanwhile in Los Angeles, the two established their first official school, the Ruth St. Denis School of Dancing and Its Related Arts, in the summer of 1915.[2]

It was not until February 6, 1915, on yet another tour, that the term "Denishawn" actually surfaced. At a performance in Portland, Oregon, a theater manager promised eight box seats to whoever could dream up the most creative name for the latest St. Denis-Shawn ballroom exhibition. The unchallenged, winning title was "The Denishawn Rose Mazurka." While the name as a whole did n0t warrant much popularity, the "Denishawn" portion attracted audience members and the press - to such an extent that the namesake couple chose to officially change their company name from the St. Denis-Shawn Company to Denishawn Dancers.[3]

With this new name and a school of their own, Shawn and St. Denis began brainstorming ways to expand their contributions to the dance world. St. Denis and Shawn renamed the school officially under the title 'The Denishawn School', and they soon began developing those movements, techniques, and innovations that are known today as the Denishawn style of dancing. The two developed a guide for their pedagogy and choreography, an excerpt of which is quoted below:

"The art of dance is too big to be encompassed by any one system. On the contrary, the dance includes all systems or schools of dance. Every way that any human being of any race or nationality, at any period of human history, has moved rhythmically to express himself, belongs to the dance. We endeavor to recognize and use all contributions of the past to the dance and will continue to use all new contributions in the future".[2]

Later years

Denishawn officially disintegrated in 1931 after Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis separated in their marriage, though the pair never divorced and continued to promote dance education through their respective endeavors. Shawn went on to purchase the property used for the Jacob's Pillow Dance center in Lee, Massachusetts, which continues to operate. In her teachings after Denishawn, St. Denis focused on spiritual and Asian influences in dance. After roughly a decade working apart, Shawn and St. Denis reunited briefly in 1941 at the Jacob's Pillow Dance festival, where they performed several works together.[4]

Technique and classes

Over the years that the school grew more widely renown, the teaching system was constantly being evolved. According to St. Denis, Shawn attributed the most to this. He addressed incoming students with a 'diagnosis lesson', which would assess their current skills in order to assign them to a specific learning/class structure for their time at the Denishawn school.[5] Shawn also was firm on his ideas of what was necessary for the learning curriculum. He addressed that ballet was an overall necessity for any dancer to move forward or thrive in their studies, which is a big reason why the Denishawn curriculum was largely based on ballet fundamentals.[6]

When taking technique classes, students danced in bare feet and wore identical one-piece black wool bathing suits.[6] Classes lasted three hours every morning. Shawn typically taught during the first block of time, leading students through stretches, limbering exercises, ballet barre and floor progressions and free-form center combinations. St. Denis then took over with instruction in Oriental and yoga techniques. Author and former Denishawn pupil Jane Sherman recalls an everyday class, laden with ballet terminology:

"A typical Denishawn class began at the barre; first came stretching, petits and grands battements, a series of plies in the five positions, sixteen measures of grande rondes de jambes, and thirty-two measures of petites rondes de jambes. These might be followed by slow releves in arabesque, fast changes, entrechats, and exercises to prepare for fouettes. In short, the works! After ballet arm exercises out on the floor, we next worked to perfect our develops en tournant, out attitudes, out renverses, and our grande jetes".[2]

Each pupil danced alone a series of pas de basques: the Denishawn version, the ballet, the Spanish, and the Hungarian. The Denishawn pas de basque was distinguished by arms held high and parallel overhead as the body made an extreme arch sideways toward the leading foot.[7]

Next usually came a free, open exercise affectionately nicknamed "arms and body," done to a waltz from Tchaikovsky's Sleeping Beauty. A forerunner of the technical warmups now used in many modern dance schools, it started with feet placed far apart and pressed flat on the floor. After a slow swinging of the body into ever-increasing circles, came head, shoulder, and torso rolls, with the arms sweeping from the floor to the ceiling followed by a relaxed run around the circumference of the studio, ending in a back fall. Other exercises included Javanese arm movements, and hand stretches to train the dancers Western fingers into going backward into some semblance of Cambodian dance flexibility.[2]

Class always closed with the learning of another part of a dance. Based on the theory that one learns to perform by performing, dance exercises were essential elements in Denishawn training, and some of them were so professionally interesting that they became part of the concert repertory.[2]

Any pupil attending classes at a Denishawn school had a wide array of classes to choose from outside of the consistent technique classes. Ted felt it important that the technique was not all too rigid, like classical ballet, and contained some less-structured forms, which brought classes on Dalcroze eurythmics as well as Delsarte laws of expressionism into the curricula. Ruth, on the other hand, emphasized the origins of dance from the foreign countries of the East, the history behind these techniques, and the method of what she called "music visualization", and added to the curricula based on these standards.[6] The couple also offered a Hawaiian Hula class taught by the dance instructor Kulamanu, as well as a class taught by Misha Ito that emphasized specificities of the technique to Japanese sword dancing. Outside of movement classes, the school had lectures, music classes, the art of dyeing and the treatment of fabrics, and libraries to study for these courses.

Schools opened

The first school that St. Denis and Shawn opened as partners was an older Spanish-style mansion in the hills of Los Angeles on St. Paul Street. It had an indoor room that was perfectly sized to fit smaller classes, a swimming pool and a tennis court for additional endurance training and/or leisure time, and the estate was filled with eucalyptus trees. Once they settled in, they built their own dancing platform over the tennis court. They also strategically built canopies over the outside space so that they could use it year-round.[5]

There were two spaces in the St. Paul school reserved for technique classes: an indoor studio where St. Denis primarily taught, and an outdoor ballroom for yoga meditations and Shawn's various classes (ballet, ballroom and what would later be called "Denishawn" technique). $500 covered the cost of a 12-week program that included daily technique classes, room and board, arts and crafts and guided reading lessons.[2] Regular classes and a lunch at the school would cost one dollar for the students. The fees would be collected in an old cigar box by one of Shawn's friends, Mary Jane Sizemore.[5]

During the second summer that the school was opened St. Denis and Shawn decided to hire a manager. Mrs. Edwina Hamilton was brought on staff at the school and was praised by Ruth for her kindness. That winter St. Denis and Shawn went on tour and left the school open and in the hands of Mrs. Hamilton and the assistant teachers. While they were on tour, the registration for upcoming classes looked promising and Mrs. Hamilton suggested that the Denishawn School find a bigger home.

Their second school location in Los Angeles was in an old house in West Lake Park and shared similar characteristics to the St. Paul Street estate. This location had a garden and a tennis court, like the previous school had. Another dance platform was built over the tennis court, a tent was placed over that, and an auditorium was positioned on one side of the area and a dressing room on the opposite side.[5] Eventually, the school went on to spreading farther than just California as Shawn and St. Denis spread their repertory and style through performing. In 1927 they opened a school on Stevenson Place in The Bronx, New York.[8]

Repertory and performance

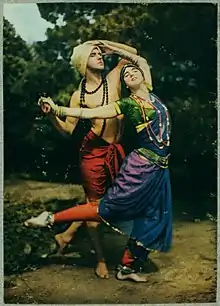

.jpg.webp)

The Denishawn Dancers took advantage of many performance opportunities – in colleges, concert halls, vaudeville theaters, convention centers and outdoor stadiums. Besides being invited to performance venues like New York's Palace Theater (1916), Denishawn was the first American company to present "serious Western dance" in Japan, Burma, China, India, Ceylon, Java, Malaya and the Philippines (1925–26)[2] In some ways, the presented work resembled ballet – each piece was a full-company story with elaborate costumes, sets and lighting. In terms of movement, however, the differences were obvious – no pointe shoes, no pas de deux lifts, no exact format for patterning solos and ensemble pieces.

Most Denishawn works fall into one of four categories:

- Orientalia: Chronologically, these were the first true Denishawn works. St. Denis was responsible for the majority of these pieces, though Shawn did put together a small number of Oriental solos and group dances. As their title suggests, these pieces incorporate aspects of East Indian movement, dress and environment (in the form of set design). A particularly famous work from this period is St. Denis's Radha, a mini-ballet set in a Hindu temple in which an exotic woman dances to honor the five senses.

- Americana: While St. Denis found her most powerful inspiration in the Far East, Shawn seemed to find his in the cultures of America. His works dominate the Americana series, complete with musical scores by American composers and portrayals of "American" characters like cowboys, Indians and ballplayers. Shawn's comic pantomime Danse Americaine, for example, centers on a soft-shoe dancer acting as a baseball player.

- Music visualizations: Inspired by Isadora Duncan's approach to music, St. Denis developed the music visualization, which she defined as "...the scientific translation into bodily action of the rhythmic, melodic and harmonious structure of a musical composition without intention to in any way 'interpret' or reveal any hidden meaning apprehended by the dancer".[2] Meaning, movement was set strictly to music without reading into anything emotionally. If the music swells, the body swells: if the music grows quiet, the body comes to rest. St. Denis's Soaring, set on five female dancers, is arguably her most well-known music visualization.

- Miscellanea: Also known as "Denishawn divertissements", these shorter works included those that cannot fit neatly into the pigeonholes of "Oriental", "Americana" and "Music Visualization".[2] These works were reserved for performances that did not require presentations of full-length ballets.

Many Denishawn solo works remain in the active repertoire of many companies. Their solos are of special interest to many for their exotic qualities. Several of their solos were included in "The Art of the Solo" presented at the Baltimore Museum of Art on September 29, 2006. These included three revival premieres, namely, Shawn's "Invocation to the Thunderbird"(1916), last danced by Denishawn dancer John Dougherty and "Death of Adonis" (1922). Both were recreated by Mino Nicolas, programme curator, with the aid of film, written accounts and photographs. Also featured were the revival premiere of Ruth St. Denis' "The Peacock/A Legend of India" (1906) which was recreated using the same methods. Her signature solo, "The Incense", will also be performed by Cynthia Word of Washington, D.C.

Pupils

During its developmental years, the first pupils to join the Denishawn school played a large role in building it up from the ground, and have even been described as "foundation stones of the system that was to spread over the country".[2] This group included Margaret Loomis, Addie Munn, Helen Eisner, Florine Goodman, Aileen Flaven, Florence Andrews (who danced under the name Florence O'Denishawn, Sadie Vanderhoff, Carol Dempster, Ada Forman, Claire Niles, Chula Monzon, and Yvonne Sinnard. The majority of these original dancers were related to close acquaintances of St.Denis and Shawn. Another well known student and employee of the Denishawn school was Pearl Wheeler. She was primarily the costumer for the school but also took classes and appeared in performances alongside the other dancers.[5]

Several notable movie stars of the early 20th century studied under the Denishawn school in their lifetimes. The Gish sisters, Dorothy and Lillian Gish, took classes from St. Denis and Shawn for some time. Lillian even worked separately with St. Denis and Ruth when she and Rosie Dolly learned a dance from the two that was to be featured in their upcoming movie, The Lily and the Rose (1915). Other notable movie stars of the time include: Louise Brooks, Ina Claire, Ruth Chatterton, Lenore Ulric, Mabel Normand, Florence Vidor, Colleen Moore, and Myrna Loy.[5]

Some pupils who had their beginnings in the Denishawn school went on to make names for themselves , and their presence at the school is sometimes overlooked in their history. For instance, 'Mother of Modern Dance' Martha Graham joined the school during its second summer. She remained there for over a half decade, learning the technique and eventually becoming a regular instructor. Ruth claimed that during her time there, she was "quiet but asked intelligent questions."[5] Another two pupils who came to Denishawn in their early careers were Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman. Humphrey moved out to California from Evanston, Illinois so that she could have the opportunity to study at the Denishawn school. St. Denis eventually told Humphrey that she should reconsider her plans to become a teacher and pursue a career in performing first. After some time studying at the school's West Lake Park, Humphrey and Weidman migrated to New York where they managed Denishawn's NY-based Denishawn house to develop their own styles and, eventually, open their own school: the Humphrey-Weidman Dance Company.[9]

See also

References

- Harbin, Billy J.; Marra, Kim; Schanke, Robert A. (2005). The Gay & Lesbian Theatrical Legacy. University of Michigan Press. p. 330.

- Sherman, Jane (1983). Denishawn: The Enduring Influence. Twayne Publishers.

- Burstyn, Joan N. (Oct 1, 1996). Past and Promise: Lives of New Jersey Women By Joan N. Burstyn, Women's Project of New Jersey. Syracuse University Press. p. 189.

- "A Guide to the Denishawn Dance Collection". www.library.ufl.edu. Denishawn School of Dancing, Shawn, Ted -- 1891-1972, St. Denis, Ruth -- 1880-1968, Denishawn Dancers. Retrieved 2018-06-30.CS1 maint: others (link)

- St. Denis, Ruth (1939). An Unfinished Life. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 172–201.

- Sherman, Jane (1979). The Drama of Denishawn Dance. Wesleyan University Press. p. 6.

- Sherman, Jane; Mumaw, Barton (1986). Barton Mumaw, Dancer: From Denishawn to Jacob’s Pillow and Beyond. Wesleyen University Press.

- http://www.denishawncentennial.com/Denishawn_House.html

- Cohen, Selma Jean; Dance Perspectives Foundation. Denishawn. Oxford University Press, 2005. Another illustrious Denishawn School (and company) alumnus was the jazz-dance innovator and choreographer Jack Cole. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195173697.001.0001/acref-9780195173697-e-0485?rskey=HM8Hfk&result=487

Further reading

| Archives at | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| How to use archival material |

| Archives at | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| How to use archival material |

- Suzanne Shelton, Divine Dancer: A Biography of Ruth St. Denis (New York: Doubleday, 1981)

- Jane Sherman, Denishawn: The Enduring Influence (Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers, 1983)

- Jane Sherman, The Drama of Denishawn Dance (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1979)