British Malaya

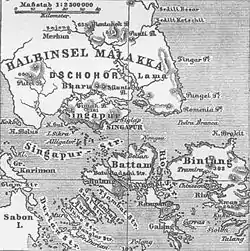

The term "British Malaya" (/məˈleɪə/; Malay: Tanah Melayu British) loosely describes a set of states on the Malay Peninsula and the island of Singapore that were brought under British hegemony or control between the 18th and the 20th centuries. Unlike the term "British India", which excludes the Indian princely states, British Malaya is often used to refer to the Federated and Unfederated Malay States, which were British protectorates with their own local rulers, as well as the Straits Settlements, which were under the sovereignty and direct rule of the British Crown, after a period of control by the East India Company.

British Malaya | |

|---|---|

| 1826–1957 | |

The Union Jack, the commonly used flag | |

.jpg.webp) British dependencies in Malaya and Singapore, 1888 | |

| Demonym(s) | British, Malayan |

| Membership | |

| Government | Imperial |

• 1826–1830 | George IV |

• 1830–1837 | William IV |

• 1837–1901 | Victoria |

• 1901–1910 | Edward VII |

• 1910–1936 | George V |

• 1936–1936 | Edward VIII |

• 1936–1941 | George VI |

• 1941–1945 | Interregnum |

• 1946–1952 | George VI |

• 1952–1957 | Elizabeth II |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| House of Lords | |

| House of Commons | |

| British Empire | |

| 17 March 1824 | |

| 27 November 1826 | |

| 20 January 1874 | |

| 8 December 1941 | |

| 12 September 1945 | |

| 1 April 1946 | |

| 1 February 1948 | |

| 18 January 1956 | |

| 31 July 1957 | |

| 31 August 1957 | |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Malaysia |

|

|

|

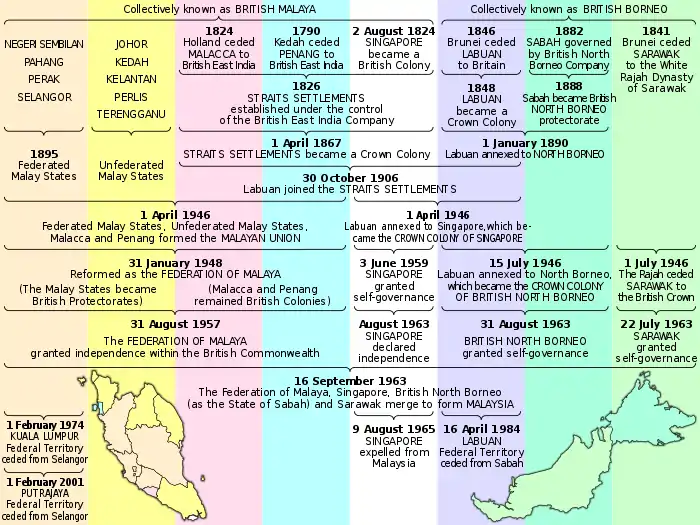

Before the formation of the Malayan Union in 1946, the territories were not placed under a single unified administration, with the exception of the immediate post-war period when a British military officer became the temporary administrator of Malaya. Instead, British Malaya comprised the Straits Settlements, the Federated Malay States, and the Unfederated Malay States. Under British hegemony, Malaya was one of the most profitable territories of the Empire, being the world's largest producer of tin and later rubber. During the Second World War, Japan ruled a part of Malaya as a single unit from Singapore.[1]

The Malayan Union was unpopular and in 1948 was dissolved and replaced by the Federation of Malaya, which became fully independent on 31 August 1957. On 16 September 1963, the federation, along with North Borneo (Sabah), Sarawak, and Singapore, formed the larger federation of Malaysia.[2]

Initial British involvement in Malay politics

The British first became formally involved in Malay politics in 1771, when Great Britain tried to set up trading posts in Penang, formerly a part of Kedah. The British colonised Singapore in 1819 and were in complete control of the state at that time.

Penang and Kedah

In the mid-18th century, British firms could be found trading in the Malay Peninsula. In April 1771, Jourdain, Sulivan and de Souza, a British firm based in Madras, India, sent Francis Light to meet the Sultan of Kedah, Sultan Muhammad Jiwa Zainal Adilin II, to open up the state's market for trading. Light was also a captain in the service of the East India Company.

.jpg.webp)

The Sultan faced external threats during this period. Siam, which was at war with Burma and which saw Kedah as its vassal state, frequently demanded that Kedah send reinforcements. Kedah, in many cases, was a reluctant ally to Siam.

After negotiations with Light, the Sultan agreed to allow Jourdain, Sulivan, and de Souza to build and operate a trading post and in Kedah, if the British agreed to protect Kedah from external threats. Light conveyed this message to his superiors in India. The East India Company, however, did not agree with the proposal.

Two years later, Sultan Muhammad Jiwa died and was succeeded by Sultan Abdullah Mahrum Shah. The new Sultan offered Light (who later became a British representative) the island of Penang in return for military assistance for Kedah. Light informed the East India Company of the Sultan's offer. The Company, however, ordered Light to take over Penang and gave him no guarantee of the military aid that the Sultan had asked for. Light later took over Penang and assured the Sultan of military assistance, despite the Company's position. Soon the Company made up its mind and told Light that they would not give any military aid to Kedah. In June 1788, Light informed the Sultan of the Company's decision. Feeling cheated, the Sultan ordered Light to leave Penang, but Light refused.

Light's refusal caused the Sultan to strengthen Kedah's military forces and to fortify Prai, a stretch of beach opposite Penang. Recognising this threat, the British moved in and razed the fort in Prai. The British thereby forced the Sultan to sign an agreement that gave the British the right to occupy Penang; in return, the Sultan would receive an annual rent of 6,000 Spanish pesos. On 1 May 1791, the Union Flag was officially raised in Penang for the first time. In 1800, Kedah ceded Prai to the British and the Sultan received an increase of 4,000 pesos in his annual rent. Penang was later named Prince of Wales Island, while Perai was renamed Province Wellesley.

In 1821, Siam invaded Kedah, sacked the capital of Alor Star, and occupied the state until 1842.

Expansion of British influence (19th century)

Before the late 19th century, the British largely practised a non-interventionist policy. Several factors such as the fluctuating supply of raw materials, and security, convinced the British to play a more active role in the Malay states.

From the 17th to the early 19th century, Malacca was a Dutch possession. During the Napoleonic Wars, between 1811 and 1815, Malacca, like other Dutch holdings in Southeast Asia, was under the occupation of the British. This was to prevent the French from claiming the Dutch possessions. When the war ended in 1815, Malacca was returned to the Dutch. In 1824 the British and the Dutch signed the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824. The treaty, among other things, legally transferred Malacca to British administration and officially divided the Malay world into two separate entities, laying the basis for the current Indonesian-Malaysian boundary.

Johor and Singapore

Modern Singapore was founded in 1819 by Sir Stamford Raffles, with a great deal of help from Major William Farquhar. Before establishing Singapore, Raffles was the Lieutenant Governor of Java from 1811 till 1815. In 1818 he was appointed to Bencoolen. Realising how the Dutch were monopolising trade in the Malay Archipelago, he was convinced that the British needed a new trading colony to counter Dutch trading power. Months of research brought him to Singapore, an island at the tip of the Malay Peninsula. The island was ruled by a temenggung.

Singapore was then under the control of Tengku Abdul Rahman, the Sultan of the Johore-Riau-Lingga Sultanate (otherwise known as the Johor Sultanate), in turn under the influence of the Dutch and the Bugis. The Sultan would never agree to a British base in Singapore. However, Tengku Abdul Rahman had become sultan only because his older brother, Tengku Hussein or Tengku Long, had been away getting married in Pahang when their father, the previous sultan, died in 1812. In Malay cultural traditions, a person must be by the side of the dying sultan to be considered as a new ruler. Tengku Abdul Rahman was present when the old sultan died. The older brother was not happy with the development, while the temenggung who was in charge of Singapore preferred Tengku Hussein to the younger brother.

The British had first acknowledged Tengku Abdul Rahman at the time of their first presence in Malacca. The situation however had changed. In 1818, Farquhar visited Tengku Hussein in the little island of Penyengat, off the coast of Bintan, the capital of the Riau Archipelago. There, new plans were drawn up, and in 1819 Raffles made a deal with Tengku Hussein. The agreement stated that the British would acknowledge Tengku Hussein as the legitimate ruler of Singapore if he allowed them to establish a trading post there. Furthermore, Tengku Hussein and the temenggung would receive a yearly stipend from the British. The treaty was ratified on 6 February 1819. With the Temenggung's help, Hussein left Penyengat, pretending that he was 'going fishing', and reached Singapore, where he was quickly installed as Sultan.

The Dutch were extremely displeased with the action of Raffles. However, with the signing of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, Dutch opposition to the British presence in Singapore receded. The treaty also divided the Sultanate of Johor into modern Johor and the new Sultanate of Riau.

Straits Settlements

After the British secured Malacca from the Dutch through the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, they aimed to centralise the administration of Penang, Malacca, and Singapore. To this end, in 1826 a framework known as the Straits Settlements was established, with Penang as its capital. Later, in 1832, the capital was moved to Singapore. While the three holdings formed the backbone of the Settlements, throughout the years Christmas Island, the Cocos Islands, Labuan, and Dinding of Perak were placed under the authority of the Straits Settlements.

Until 1867, the Straits Settlements were answerable to the British administrator of the East India Company in Calcutta. The Settlements' administrators were dissatisfied with the way Calcutta was handling their affairs and they complained to London. In 1856 the Company even tried to annul Singapore's free port status.

In 1858, following the Indian Mutiny, the East India Company was dissolved and British India came under the direct rule of the Crown, which was exercised by the Secretary of State for India and the Viceroy of India. With Calcutta's waning power, and after intense lobbying by the administrators of the Settlements, in 1867 they were declared a crown colony and placed directly under the control of the Colonial Office in London. However, the declaration gave the colony a considerable degree of self-government within the British Empire.

In 1946, after the Second World War, the colony was dissolved. Malacca and Penang were absorbed into the new Malayan Union, while Singapore was separated from the rest of the former colony and made into a new crown colony on its own. The Malayan Union was later replaced with the Federation of Malaya in 1948, and in 1963, together with North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore, formed an enlarged federation called Malaysia.

Northern Malay states and Siam

.svg.png.webp)

Prior to the late 19th century, the British East India Company was interested only in trading, and tried as much as possible to steer clear of Malay politics. However, Siam's influence in the northern Malay states, especially Kedah, Terengganu, Kelantan and Pattani, was preventing the Company from trading in peace. Therefore, in 1826, the British, through the Company, signed a secret treaty known today as the Burney Treaty with the King of Siam. The four Malay states were not present during the signing of the agreement. In that treaty, British acknowledged Siamese sovereignty over all those states. In return, Siam accepted British ownership of Penang and Province Wellesley and allowed the Company to trade in Terengganu and Kelantan unimpeded.

83 years later, a new treaty now known as the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909 or the Bangkok Treaty of 1909 was signed between the two powers. In the new agreement, Siam agreed to give up its claim over Kedah, Perlis, Terengganu and Kelantan, while Pattani remained Siamese territory. Perlis was previously part of Kedah but during the Siamese reign it was separated from Kedah. Kedah's district of Satun however was annexed by Siam in the same agreement. Pattani on the other hand was dissected into Pattani proper, Yala and Narathiwat after the signing of the treaty.

Though the Siamese King Chulalongkorn was reluctant to sign the treaty, increasing French pressure on the Siamese eastern border forced Siam to co-operate with the British. Like Rama IV, Chulalongkorn hoped that the British would leave Siam alone if he acceded to their demands. Earlier in 1893, Siam had lost the Shan region of north-eastern Burma to the British. This demarcation as stated in the agreement remains today the Malaysia-Thailand Border.

Malay rulers did not acknowledge the agreement, but were too weak to resist British influence. In Kedah after the Bangkok Treaty, George Maxwell was posted by the British in Kedah as the sultan's advisor. The British effectively took over economic planning and execution. A rail line was built to connect Kedah with Siam in 1912 while land reform was introduced in 1914. Only in 1923 did the ruler of Kedah, Sultan Abdul Hamid Halim Shah, accept a British advisor.

Perlis had a similar experience. The ruler did not recognise the 1909 treaty but the British were de facto administrators of the state. It was only in 1930 that the ruler Raja Syed Alwi recognised the British presence in Perlis by admitting Meadows Frost as the first British advisor in Perlis.

Pangkor Treaty and Perak

Perak is a state on the western shore of the Malay Peninsula. In the 18th and 19th centuries it was discovered to be rich in tin, with the richest alluvial deposits of tin in the world. Europe at the same time was undergoing an industrial revolution and this created a huge demand for tin. The British as well as the Dutch were active in the states, each seeking to monopolise production of tin and other commodities. However, the political atmosphere in Perak was sufficiently volatile to raise the cost of tin mining operations. For instance, in 1818 Siam ordered Kedah to attack Perak. The lack of security in Perak forced the British to protect Perak in 1826.

As Perak continued to increase its mining operations, it suffered a shortage of labour. Looking to solve the problem, Malay administrator Long Jaafar invited the Chinese in Penang to work in Perak, particularly at Larut. By the 1840s, Perak's Chinese population exploded. The new immigrants more often than not were members of Chinese secret societies. Two of the largest were Ghee Hin and Hai San. These two groups regularly tried to increase their influence in Perak and this resulted in frequent skirmishes. These skirmishes were getting out of hand, so that even Ngah Ibrahim, the Menteri Besar, or chief minister, was unable to enforce the rule of law.

Meanwhile, there was a power struggle in the Perak royal court. Sultan Ali died in 1871 and the next in line for the throne was the Raja Muda Raja Abdullah. Despite that fact, he was not present during the burial of the sultan. As in the case of Tengku Hussein of Johor, Raja Abdullah was not appointed as the new sultan by the ministers of Perak. Instead the second in line, Raja Ismail, became the next sultan of Perak.

Raja Abdullah was furious and refused to accept the news kindly. He then sought and gathered political support from various channels, including several of Perak's local chiefs and several British personnel with whom he had done business in the past, with the secret societies becoming their proxies in the fight for the throne. Among those British individuals was British trader W. H. M. Read. Furthermore, he promised to accept a British advisor if the British recognised him as the legitimate ruler of Perak.

Unfortunately for Raja Abdullah, the Straits Settlements governor at that time was Sir Harry Ord and the governor was a friend of Ngah Ibrahim, who had unresolved issues with Raja Abdullah. With Ord's aid, Ngah Ibrahim sent sepoy troops from India to prevent Raja Abdullah from actively claiming the throne and extending control over the Chinese secret societies.

By 1873 the Colonial Office in London came to perceive Ord as incompetent. He was soon replaced by Sir Andrew Clarke and Clarke was ordered to get a complete picture of what was happening in the Malay states and recommend how to streamline British administration in Malaya. The reason was that London was increasingly aware that the Straits Settlements were increasingly dependent on the economy of the Malay states, including Perak. After Clarke's arrival in Singapore, many British traders including Read became close to the governor. Through Read, Clarke learned of Raja Abdullah's problem and willingness to accept a British representative in his court if the British assisted the once apparent heir.

Clarke seized the opportunity to expand British influence. First, he called all Chinese secret societies together and demanded a permanent truce. Later, through the signing of the Pangkor Treaty on 20 January 1874, Clarke acknowledged Raja Abdullah as the legitimate sultan of Perak. Immediately, J.W.W. Birch was appointed as a British resident in Perak. Raja Ismail, on the other hand, while not party to the agreement, was forced to abdicate due to intense external pressure applied by Clarke.

Selangor

Selangor just to the south of Perak also had considerable deposits of tin around Hulu Selangor on the north, Hulu Klang in the central area and Lukut near Negeri Sembilan to the south. Around 1840, under the leadership of Raja Jumaat from Riau, tin mining became a huge enterprise. His efforts soon were rewarded by Sultan Muhammad of Selangor; Raja Jumaat was appointed as Lukut's administrator in 1846. By the 1850s the area emerged as one of the most modern settlements on the Malay Peninsula apart from the Straits Settlements. At one point, there were no less than 20,000 labourers, most of them ethnic Chinese imported from China. He died in 1864 and his death created a leadership vacuum. Slowly, Lukut slid backward and was forgotten.

Meanwhile, Hulu Klang enjoyed unprecedented growth due to tin mining. Between 1849 and 1850, Raja Abdullah bin Raja Jaafar, Raja Jumaat's cousin, was appointed by the sultan as Klang's administrator. As Lukut's economic importance was slowly declining, that of Hulu Klang was rising. This attracted many labourers to relocate there, especially Chinese immigrants who had worked in Lukut. One person responsible for persuading the Chinese to move from Lukut to Hulu Klang was Sutan Puasa from Ampang. He supplied the mining colonies in Hulu Klang with goods ranging from rice to opium. As Hulu Klang prospered, several settlements started to rise up by the late 1860s. Two of them were Kuala Lumpur and Klang. A Chinese kapitan named Yap Ah Loy was instrumental in developing Kuala Lumpur.

As in Perak, this rapid development attracted great interest from the British in the Straits Settlements. The economy of Selangor became important enough to the prosperity of the Straits Settlements that any disturbance in that state would hurt the Straits Settlements themselves. Therefore, the British felt they needed to have a say in Selangor politics. One major disturbance, amounting to a civil war, was the Klang War which began in 1867.

In November 1873, a ship from Penang was attacked by pirates near Kuala Langat, Selangor. A court was assembled near Jugra and suspected pirates were sentenced to death. The sultan expressed concern and requested assistance from Sir Andrew Clarke. Frank Swettenham was appointed to serve as the sultan's advisor. Approximately a year later, a lawyer from Singapore named J. G. Davidson was appointed as British Resident in Selangor. Frank Swettenham was nominated for the Resident post but he was deemed too young.

The civil war ended in 1874.

Sungei Ujong, Negeri Sembilan

Negeri Sembilan was another major producer of tin in Malaya. In 1869 a power struggle arose between Tengku Antah and Tengku Ahmad Tunggal, as both aspired to become the next ruler of Negeri Sembilan, the Yamtuan Besar. This conflict between the two princes divided the confederation and threatened the reliability of tin supply from Negeri Sembilan.

Sungei Ujong, a state within the confederation in particular was the site of many locally important mines. It was ruled by Dato' Kelana Sendeng. However, another local chieftain named Dato' Bandar Kulop Tunggal had more influence than Dato' Kelana. Dato' Bandar received great support from the locals and even from the Chinese immigrants who worked at the mines of Sungai Ujong. Dato' Kelana's limited popularity made him dependent on another chieftain named Sayid Abdul Rahman, who was the confederation's Laksamana Raja Laut (roughly royal sea admiral). The strained relationship between Dato' Bandar and Dato' Kelana caused frequent disturbances in Sungai Ujong.

The years before 1873 however were years of relative calm as Dato' Kelana had to give extra attention to Sungai Linggi as Rembau, another state within the confederation, tried to wrest Sungai Linggi from Sungai Ujong's control. Negeri Sembilan at that time was connected to Malacca via Sungai Linggi, and a high volume of trade passed through Sungai Linggi daily. Whoever controlled Sungai Linggi would gain wealth simply through taxes.

Later that year, Dato' Kelana Sendeng died. In early 1873, Sayid Abdul Rahman took his place, becoming the new Dato' Kelana. The death however did not repair the relationship between Dato' Kelana and Dato' Bandar. On the contrary, it deteriorated. The new Dato' Kelana was deeply concerned with Dato' Bandar's unchecked influence, and sought ways to counter his adversary's power.

When the British changed their non-interventionist policy in 1873 by replacing Sir Harry Ord with Sir Andrew Clarke as the new governor of the Straits Settlements, Dato' Kelana immediately realised that the British could strengthen his position in Sungai Ujong. Dato' Kelana wasted no time in contacting and lobbying the British in Malacca to support him. In April 1874, Sir Andrew Clarke seized Dato' Kelana's request as a means to build British presence in Sungai Ujong and Negeri Sembilan in general. Clarke acknowledged Dato' Kelana as the legitimate chief of Sungai Ujong. The British and Dato' Kelana signed a treaty which required Dato' Kelana to rule Sungai Ujong justly, protect traders, and prevent any anti-British action there. Dato' Bandar was not invited to sign the agreement and hence asserted that he was not bound by the agreement. Moreover, Dato' Bandar and the locals disapproved of the British presence in Sungai Ujong. This further made Dato' Kelana unpopular there.

Soon, a company led by William A. Pickering, of the Chinese Protectorate from the Straits Settlements, was sent to Sungai Ujong to assess the situation. He recognised the predicament Dato' Kelana was in and reported back to the Straits Settlements. This prompted the British to send 160 soldiers to Sungai Ujong to help Pickering defeat Dato' Bandar. At the end of 1874, Dato' Bandar fled to Kepayang. Despite this defeat, the British paid him a pension and granted him asylum in Singapore.

As the year progressed, British influence increased to the point that an assistant resident was placed there to advise and assist Dato' Kelana with the governance of Sungai Ujong.

Pahang

The British became involved in the administration of Pahang after a civil war between two candidates to the kingdom's throne between 1858 and 1863.

Centralisation (1890s–1910s)

.svg.png.webp)

To streamline the administration of the Malay states, and especially to protect and further develop the lucrative trade in tin-mining and rubber, Britain sought to consolidate and centralise control by federating the four contiguous states of Selangor, Perak, Negeri Sembilan and Pahang into a new entity, the Federated Malay States (FMS), with Kuala Lumpur as its capital. The Residents-General administered the federation but compromised by allowing the Sultans to retain limited powers as the authority on Islam and Malay customs. Modern legislation was introduced with the creation of the Federal Council. Although the Sultans had less power than their counterparts in the Unfederated Malay States, the FMS enjoyed a much higher degree of modernisation. Federalisation also brought benefit through cooperative economic development, as evident in the earlier period, when Pahang was developed using funds from the revenue of Selangor and Perak.

The Unfederated Malay States, on the other hand, maintained their quasi-independence, had more autonomy, and instead of having a Resident they were required only to accept a British Advisor, though in reality they were still bound by treaty to accept the advice. The British undertook far less economic exploitation as they primarily wished to just keep these states in line. Indeed, limited economic potential in these states saved the UFMS from further British political meddling.[3] Perlis, Kedah, Kelantan and Terengganu were surrendered by Siam after the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909. Independent Johor, meanwhile, had to surrender Singapore to the British earlier on. Despite the Sultan's political effort, he was forced to accept an advisor in 1914, becoming the last Malay state to lose its sovereignty (British involvement in Johor actually began as early as 1885).

This period of slow consolidation of power into a centralised government and compromise—the Sultans retain their reign but not rule in their states—would have a great impact on the later road to nationhood. It effectively marked the transition of the idea of Malay states as a collective of lands governed by feudal rulers to a more Westminster-style federal constitutional monarchy. This became the accepted model for the future Federation of Malaya and ultimately Malaysia, distinguishing the nation in a region where other countries adopted stricter, heavily centralised administrations.

By 1910 the British had established seven polities on the Malay Peninsula – the Straits Settlements, the Federated Malay States and the standalone protectorates of Perlis, Kedah, Kelantan, Terengganu and Johore. The First World War had a limited impact on Malaya, with notable events including the Battle of Penang and the Kelantan rebellion.

Decentralisation (1920s)

The unfederated Malay states in blue

The

The

British policy in the late 19th and the early 20th century had been the centralisation of the Federated Malay States (FMS), which was headed by the High Commissioner, who was also the governor of the Straits Settlements. All four British Residents, who acted as a British representative in the FMS were answerable to a Resident General in the FMS capital Kuala Lumpur, who in turn reported back to High Commissioner. Crucial state government departments had to report to their federal headquarters in Kuala Lumpur. Meanwhile, the Unfederated Malay States (UMS) began to receive British advisers but they remained more independent than the FMS.[4]

In 1909 however, High Commissioner Sir John Anderson expressed concerns over over-centralisation, which was marginalisation local sultans away from policymaking. The British had a formal pro-Malay policy and the colonial administrators were careful in developing mutual trust with the Malay sultans. However, the centralisation had eroded the trust, which the some British officials felt important to regain.[5] This led to the creation of Federal Council, which the sultans were members along with representatives from the colonial government and members of the non-Malay communities. The creation of the council however failed to distribute powers to the individuals FMS states. Another attempt at decentralisation as carried out in 1925 by Sir Laurence Guillemard, the High Commissioner from 1920 to 1927, which was termed as the Decentralisation Debate of 1925-1927. During the 1920s, the British also began affirmative action for the Malays in the FMS civil service to further entice the UFMS to join the federation by proving that the Malays would have a role in the running of the government.[6] While the Malays supported the proposal because it would give them more powers, Chinese merchants and British planters argued against it, fearing decentralisation would affect efficiency badly and slow effort at building a unified modern state. The next High Commissioner, Sir Cecil Clementi, arriving from Hong Kong in 1930, pushed harder for decentralisation, believing that it would entice the UMS to join the FMS, forming a Malayan union. He envisaged the union would eventually be joined by the Straits Settlements as well as the British Borneo.[7]

Economic depression (1930s)

During the 1930s, the world economy was in a depression. Due to the integration of the Malayan economy to the global supply chain, Malaya did not escape the depression.

The Second World War (1941–1945)

The First World War did not affect Malaya directly, aside from a naval skirmish between the renegade German cruiser SMS Emden and the Russian cruiser Zhemchug off the coast of George Town, in what became known as the Battle of Penang.

The Second World War however consumed the country. Japan invaded Malaya in 1941, as part of the coordinated attack that started at Pearl Harbor. Malaya and Singapore were under Japanese occupation from 1942 until 1945. Japan rewarded Siam for its co-operation during this period by giving it the state of Perlis, Kedah, Kelantan and Terengganu. The rest of Malaya was governed as a single colony from Singapore.[1]

After Japan's surrender at the end of the Second World War, Malaya and Singapore were placed under British Military Administration.

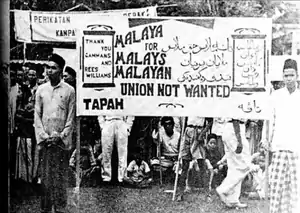

Decolonisation (1945–1963)

Within a year after the Second World War, the loose administration of British Malaya was finally consolidated with the formation of the Malayan Union on 1 April 1946. Singapore, however, was not included and was considered a crown colony by itself. The new Union was greeted with strong opposition from the local Malays. The opposition revolved around two issues: loose citizenship requirements and reduction in the Malay rulers' power. Due to the pressure exerted, the Union was replaced with the Federation of Malaya on 31 January 1948. The Federation achieved independence on 31 August 1957. All Malayan states later formed a larger federation called Malaysia on 16 September 1963 together with Singapore, Sarawak and North Borneo. Singapore was expelled from the federation on 9 August 1965.

References

- Notes

- Cheah Boon Kheng 1983, p. 28.

- C. Northcote Parkinson, "The British in Malaya" History Today (June 1956) 6#6 pp 367-375.

- Sani 2008, p. 12.

- Comber 1983, pp. 9-10.

- Sani 2008, p. 14.

- Roff 1967, pp. 117–118.

- Comber 1983, pp. 11-14.

- Bibliography

- Cheah Boon Kheng (1983). Red Star over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict during and after the Japanese Occupation, 1941-1946. Singapore University Press. ISBN 9971695081.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 478.

- Comber, Leon (1983). 13 May 1969: A Historical Survey of Sino-Malay Relations. Heinemann Asia. ISBN 978-967-925-001-5.

- Lees, Lynn Hollen. Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1786-1941 (Cambridge University Press, 2017). online review

- Osborne, Milton (2000). Southeast Asia: An Introductory History. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-390-9.

- Parkinson, C. Northcote. "The British in Malaya" History Today (June 1956) 6#6 pp 367-375.

- Roff, Willam R. (1967). The Origins of Malay Nationalism. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-9676530592.

- Sani, Rustam (2008). Social roots of the Malay Left: an analysis of the Kesatuan Melayu Muda. SIRD. ISBN 9833782442.

- Wright, Arnold; Cartwright, H. A. (1908). Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources. Lloyd's Greater Britain publishing Company.

- Zainal Abidin bin Abdul Wahid; Khoo Kay Kim; Muhd Yusof bin Ibrahim; D.S. Ranjit Singh (1994). Kurikulum Bersepadu Sekolah Menengah Sejarah Tingkatan 2. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. ISBN 983-62-1009-1.

Further reading

- Firaci, Biagio (10 June 2014). "Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles and the British Colonization of Singapore among Penang, Melaka and Bencoonen".

- Arkib Negara. Hari ini dalam sejarah. Penubuhan Majlis Persekutuan at the Wayback Machine (archived 9 June 2007)

- Malaysia Design Archive | 1850 to 1943: Modernisation