Derek Bailey (guitarist)

Derek Bailey (29 January 1930 – 25 December 2005) was an English avant-garde guitarist and an important figure in the free improvisation movement.[1] Bailey abandoned conventional performance techniques found in jazz, exploring atonality, noise, and whatever unusual sounds he could produce with the guitar. Much of his work was released on his own label Incus Records. In addition to solo work, Bailey collaborated frequently with other musicians and recorded with collectives such as Spontaneous Music Ensemble and Company.[2]

Derek Bailey | |

|---|---|

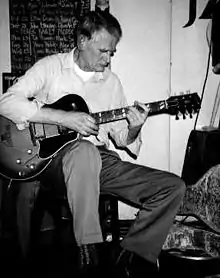

Bailey at the Vortex Club, Stoke Newington, 1991 | |

| Background information | |

| Born | 29 January 1930 Sheffield, England |

| Died | 25 December 2005 (aged 75) London, England |

| Genres | Free improvisation, avant-garde, European free jazz |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, record label owner |

| Instruments | Guitar |

| Years active | 1950s–2000s |

| Labels | Incus |

| Associated acts | Joseph Holbrooke, Spontaneous Music Ensemble, Tony Oxley, Evan Parker, Iskra, Company, Jazz Composer's Orchestra, Han Bennink |

Career

Bailey was born in Sheffield, England. A third-generation musician,[2] he began playing guitar at the age of ten. He studied with Sheffield City organist C. H. C. Biltcliffe,[2] an experience he disliked,[3] and with his uncle George Wing and John Duarte.[2] As an adult he worked as a guitarist and session musician in clubs, radio, and dance hall bands, playing with Morecambe and Wise, Gracie Fields, Bob Monkhouse, Kathy Kirby, and on the television program Opportunity Knocks.

Bailey's earliest foray into free improvisation was in 1953 with two guitarists in Glasgow.[4] He was part of a trio founded in 1963 with Tony Oxley and Gavin Bryars called Joseph Holbrooke,[2] named after English composer Joseph Holbrooke, although the group never played his work. The band played conventional jazz at first, but later moved in the direction of free jazz.[5]

In 1966, Bailey moved to London.[2] At the Little Theatre Club run by drummer John Stevens, he met like-minded musicians such as saxophonist Evan Parker, trumpeter Kenny Wheeler, and double bassist Dave Holland, with whom he formed the Spontaneous Music Ensemble.[2] In 1968 they recorded Karyobin for Island Records. Bailey formed the Music Improvisation Company with Parker, percussionist Jamie Muir, and Hugh Davies on homemade electronics. The band continued until 1971. He was a member of the Jazz Composer's Orchestra and formed the trio Iskra 1903 with double bassist Barry Guy and trombonist Paul Rutherford[2] that was named after a newspaper published by Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin.[6] He was a member of Oxley's sextet until 1973.[2]

In 1970, Bailey founded the record label Incus[2] with Tony Oxley, Evan Parker, and Michael Walters. It was the first musician-owned independent label in the UK. Oxley and Walters left early in the label's history; Parker and Bailey continued as co-directors until the mid-1980s, when friction between them led to Parker's departure. Bailey continued the label with his partner Karen Brookman until his death in 2005.

With other musicians, Bailey was a co-founder in 1975 of Musics magazine, described as "an impromental experivisation arts magazine".[7]

In 1976, Bailey started the collaborative project Company,[2] which at various times included Han Bennink, Steve Beresford, Anthony Braxton, Buckethead, Eugene Chadbourne, Lol Coxhill, Johnny Dyani, Fred Frith, Tristan Honsinger, Henry Kaiser, Steve Lacy, Keshavan Maslak, Misha Mengelberg, Wadada Leo Smith, and John Zorn. Bailey organized the annual music festival Company Week, which lasted until 1994. In 1980, he wrote the book Improvisation: Its Nature and Practice.[2] In 1992, the book was adapted by Channel 4 in the UK into a four-part TV series, On the Edge: Improvisation in Music, which was narrated by Bailey.

Bailey died in London on Christmas Day in 2005. He had been suffering from motor neurone disease.[8]

Music

For listeners unfamiliar with experimental music, Bailey's distinctive style can be challenging. Its most noticeable feature is its extreme discontinuity, often from note to note. There may be enormous intervals between consecutive notes, and rather than aspiring to the consistency of timbre typical of most guitar-playing, Bailey interrupts it as much as possible. Four consecutive notes, for instance, may be played on an open string, a fretted string, via harmonics, and using a nonstandard technique such as scraping the string with the pick or plucking below the bridge.

Playing both acoustic and electric guitars (although more usually the latter), Bailey extended the possibilities of the instrument in radical ways, obtaining wider array of sounds than are usually heard. He explored the full vocabulary of the instrument, producing timbres and tones ranging from the most delicate tinklings to fierce noise attacks. (The sounds he produced have been compared to those made by John Cage's prepared piano.) Typically, he played a conventional instrument, in standard tuning, but his use of amplification was often crucial. In the 1970 his standard set-up involved two independently controlled amplifiers to give a stereo effect onstage, and he often would use the swell pedal to counteract the normal attack and decay of notes. He made original use of feedback, a technique demonstrated on the album String Theory (Paratactile, 2000). Throughout both his commercial and improvising careers his principal guitar was a 1963 Gibson ES 175 model.[9]

Although Bailey occasionally made use of prepared guitar in the 1970s (he would, for example, put paper clips on the strings, wrap his instruments in chains, or add further strings to the guitar), often for Dadaist/theatrical effect, by the end of that decade he had, in his own words, "dumped" such methods.[10] Bailey argued that his approach to music-making was actually far more orthodox than performers such as Keith Rowe of the improvising collective AMM, who treats the guitar purely as a "sound source" rather than as a musical instrument. Instead, Bailey preferred to "look for whatever 'effects' I might need through technique".[10]

Eschewing labels such as "jazz" and "free jazz", Bailey described his music as "non-idiomatic". In the second edition of his book Improvisation..., Bailey indicated that he felt that free improvisation was no longer "non-idiomatic" in his sense of the word, as it had become a recognizable genre and musical style itself. Bailey frequently sought performance contexts that would provide new stimulations and challenge that would prove musically "interesting", as he often put it. This led to work with collaborators such as Pat Metheny, John Zorn, Lee Konitz, David Sylvian, Cyro Baptista, Cecil Taylor, Keiji Haino, tap dancer Will Gaines, Drum 'n' Bass DJ Ninj, Susie Ibarra, Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth and the Japanese noise rock group Ruins. Despite often performing and recording in a solo context, he was far more interested in the dynamics and challenges of working with other musicians, especially those who did not necessarily share his approach. As he put it in a March 2002 article of Jazziz magazine:

There has to be some degree, not just of unfamiliarity, but incompatibility [with a partner]. Otherwise, what are you improvising for? What are you improvising with or around? You've got to find somewhere where you can work. If there are no difficulties, it seems to me that there's pretty much no point in playing. I find that the things that excite me are trying to make something work. And when it does work, it's the most fantastic thing. Maybe the most obvious analogy would be the grit that produces the pearl in an oyster, or some shit like that.[11]

Bailey was also known for his dry sense of humour. In 1977, Musics magazine sent the question "What happens to time-awareness during improvisation?" to about thirty musicians associated with the free improvisation scene. The answers received answers that varied from long, and theoretical essays to plain, direct comments. Typically pithy was Bailey's reply: "The ticks turn into tocks and the tocks turn into ticks."[12]

Mirakle, a 1999 recording released in 2000, shows Bailey moving into the free funk genre, performing with bassist Jamaaladeen Tacuma and drummer Grant Calvin Weston. Carpal Tunnel, the last album to be released during his lifetime, documented his struggle with the Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in his right hand which had rendered him unable to grip a plectrum. This problem marked the onset of Lou Gehrig's disease. Characteristically, he refused invasive surgery to treat his condition, instead being more "interested in finding ways to work around" this limitation. He chose to "relearn" guitar playing techniques by utilising his right thumb and index fingers to pluck the strings.

Discography

As leader

- 1970 The Topography of the Lungs with Han Bennink and Evan Parker (Incus)

- 1971 Solo Guitar (Incus)

- 1971 Improvisations for Cello and Guitar with Dave Holland (ECM)

- 1974 First Duo Concert with Anthony Braxton (Emanem)

- 1975 The London Concert with Evan Parker (Incus)

- 1977 Drops with Andrea Centazzo (Ictus)

- 1979 Time with Tony Coe (Incus)

- 1980 Aida (Incus)

- 1980 Views from Six Windows with Christine Jeffrey (Metalanguage)

- 1981 Dart Drug with Jamie Muir (Incus)

- 1983 Yankees with George Lewis and John Zorn (Celluloid)

- 1985 Notes: Solo Improvisations (Incus)

- 1986 Compatibles with Evan Parker (Incus)

- 1987 Moment Précieux with Anthony Braxton (Victo)

- 1988 Cyro with Cyro Baptista (Incus)

- 1990 Figuring with Barre Phillips (Incus)

- 1992 Village Life with Louis Moholo, Thebe Lipere (Incus)

- 1993 Wireforks with Henry Kaiser (Shanachie)

- 1993 Playing (Incus)

- 1994 Drop Me Off at 96th (Scatter)

- 1995 Saisoro with the Ruins (Tzadik)

- 1995 Harras with William Parker, John Zorn (Avant)

- 1995 Banter with Gregg Bendian (OODiscs)

- 1996 Close to the Kitchen with Noel Akchote (Rectangle)

- 1996 Lace (Emanem)

- 1996 Guitar, Drums 'n' Bass (Avant)

- 1997 Music & Dance (Revenant)

- 1997 And with Pat Thomas, Steve Noble (Rectangle)

- 1997 Takes Fakes and Dead She Dances (Incus)

- 1997 Trio Playing (Incus)

- 1998 Tohjinbo (Paratactile)

- 1998 Viper with Min Xiaofen (Avant)

- 1998 No Waiting with Joelle Leandre (Potlatch)

- 1998 Dynamics of the Impromptu with John Stevens, Trevor Watts (Entropy Stereo)

- 1999 Arch Duo with Evan Parker (Ratascan)

- 1999 Playbacks (Bingo)

- 1999 Outcome with Steve Lacy (Potlatch)

- 1999 Daedal with Susie Ibarra (Incus)

- 2000 Locational with Alex Ward (Incus)

- 2000 String Theory (Paratactile)

- 2000 Mirakle with Jamaaladeen Tacuma, Calvin Weston (Tzadik)

- 2000 Songs with Keiji Haino (Incus)

- 2001 Llaer with Ingar Zach (Sofa)

- 2001 Fish with Shoji Hano (PSF)

- 2001 Ore with Eddie Prévost (Arrival)

- 2002 Barcelona with Agusti Fernandez (Hopscotch)

- 2002 Ballads (Tzadik)

- 2002 Right Off with Carlos Bechegas (Numerica)

- 2002 Duos, London 2001 (Incus)

- 2002 Bailey/Hautzinger with Franz Hautzinger (Grob)

- 2002 Pieces for Guitar (Tzadik)

- 2002 New Sights Old Sounds (Incus)

- 2003 Soshin with Fred Frith, Antoine Berthiaume (Ambiances Magnetiques) Antoine Berthiaume at the Wayback Machine (archived 10 February 2010))

- 2003 Nearly a D with Frode Gjerstad (Emanem)

- 2004 Scale Points on the Fever Curve with Milo Fine (Emanem)

- 2005 Carpal Tunnel (Tzadik)

- 2006 To Play: The Blemish Sessions (Samadhisound)

- 2006 Derek with Cyro Baptista (Amulet)

- 2007 Standards (Tzadik)

- 2008 Tony Oxley Derek Bailey Quartet (Jazzwerkstatt)

- 2009 Good Cop Bad Cop with Tony Bevan, Paul Hession & Ōtomo Yoshihide (No-Fi)

- 2010 More 74: Solo Guitar Improvisations (Incus)

- 2011 Close to the Kitchen (Rectangle)

- 2012 Derek Bailey Plus One Music Ensemble (Nondo)

Source:[13]

As co-leader

With Company

- The Music Improvisation Company (ECM, 1970)

- The Music Improvisation Company 1968-1971 (Incus, 1976)

- Company 6 & 7 (Incus, 1992)

- Once (2004)

With Iskra

- Iskra 1903 with Paul Rutherford and Barry Guy (Incus, 1972)

- Chapter One: 1970–1972 (2000)

- Buzz (2002)

- 65 (Rehearsal Extract) (1999)

- Joseph Holbrooke '98 (2000)

- The Moat Recordings (Tzadik, 2006)

With the Spontaneous Music Ensemble

- Karyobin (Island, 1968)

- Withdrawal (1997)

- Quintessence (Emanem, 2007)

With others

- Globe Unity 67 & 70, Globe Unity Orchestra (1970)

- Ode, Barry Guy/The London Jazz Composers' Orchestra (Incus, 1972)

- Groupcomposing with Han Bennink/Peter Bennink/Peter Brötzmann/Misha Mengelberg/Evan Parker/Paul Rutherford (Instant Composers Pool, 1978)

- The Sign of Four, with Pat Metheny, Gregg Bendian, Paul Wertico (Knitting Factory, 1997)

Source:[14]

As sideman

With Steve Lacy

- Saxophone Special (1974)

- The Crust (1975)

- Dreams (1975)

With Tony Oxley

- The Baptised Traveller (1969)

- 4 Compositions for Sextet (1970)

- Ichnos (1971)

With John Zorn

- The Big Gundown (1985)

- Cobra: John Zorn's Game Pieces Volume 2 (2002)

With others

- European Echoes, Manfred Schoof (1969)

- Nipples, Peter Brötzmann (1969)

- Song for Someone, Kenny Wheeler (Incus, 1973)

- First Duo Concert, Anthony Braxton (1974)

- Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet/The Sinking of the Titanic, Gavin Bryars (Obscure, 1975)

- Les Douzes Sons, Joëlle Léandre (1983)

- Pleistozaen Mit Wasser, Cecil Taylor (1988)

- Boogie with the Hook, Eugene Chadbourne (1996)

- The Last Wave, Arcana (DIW, 1996)

- Legend of the Blood Yeti, Thurston Moore (Infinite Chug, 1997)

- Hello, Goodbye, Frode Gjerstad (2001)

- Vortices and Angels, John Butcher (2001)

- Blemish, David Sylvian (Samadhisound, 2003)

- Domo Arigato Derek Sensei, Henry Kaiser (2005)

Source:[14]

References

- Cook, Richard (2005). Richard Cook's Jazz Encyclopedia. London: Penguin Books. p. 28. ISBN 0-141-00646-3.

- Kelsey, Chris. "Derek Bailey". AllMusic. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- Watson, Ben – Derek Bailey and the Story of Free Improvisation. ISBN 1-84467-003-1 p. 25.

- Watson, Ben – Derek Bailey and the Story of Free Improvisation. ISBN 1-84467-003-1 p. 35.

- Bryars, Gavin (30 November 2009). "Joseph Holbrooke Trio: The Moat Studio Recordings | Gavin Bryars". gavinbryars.com. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- Watson, Ben – Derek Bailey and the Story of Free Improvisation. ISBN 1-84467-003-1 p. 158.

- "College Archives: Little magazines". King's College London. Archived from the original on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- Fordham, John (29 December 2005). "Derek Bailey". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- "Derek Bailey's guitar by John Russell". Incusrecords.force9.co.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "Correspondence with bailey from 1997, quoted at". Efi.group.shef.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "''Jazziz'', March 2002, quoted at". Bagatellen.com. 26 December 2005. Archived from the original on 13 January 2006. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "''Musics'', no. 10, November 1976, quoted at". Efi.group.shef.ac.uk. 12 October 1953. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "Derek Bailey | Album Discography". AllMusic. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- "Derek Bailey | Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

Further reading

- Bailey, Derek. Improvisation: Its Nature and Practice, revised edition (1992) The British Library National Sound Archive (UK); Da Capo Press (US); ISBN 978-0-306-80528-8

- Clark, Philip. The Wire Primers: A Guide to Modern Music: Derek Bailey, pages 121–129; Verso, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84467-427-5

- Lash, Dominic. 2011. "Derek Bailey's Practice/Practise". Perspectives of New Music 49, No. 1 (Winter): 143–71.

- Watson, Ben. Derek Bailey and the Story of Free Improvisation. ISBN 1-84467-003-1

External links

- Sample of Derek Bailey's playing 1

- Sample of Derek Bailey's playing 2

- Sample of Derek Bailey's playing 3

- Sample of Derek Bailey's playing 4 (with Han Benninik)

- Derek Bailey interview 1

- Derek Bailey interview 2

- European Free Improvisation index page on Bailey

- Video footage of Derek Bailey playing

- Video footage of Derek Bailey playing with tap dancer Will Gaines

- "I Miss a Friend Like You" from The Gospel Record, Shaking Ray Records, 2005

- Obituary by Steve Voce in The Independent

- Obituary by John Fordham in The Guardian

- Appreciation by Gavin Bryars in The Guardian

- Tributes at the Wayback Machine (archived 13 October 2007) from The Wire magazine

- Audio Recordings of WCUW Jazz Festivals – Jazz History Database at the Wayback Machine (archived 26 March 2010)

- at 05:54 Derek Bailey at the Claxon Sound Festival for improvised music in The Netherlands (Theo Uittenbogaard/VPRO/1984)