Pat Metheny

Patrick Bruce Metheny (/məˈθiːni/ mə-THEE-nee; born August 12, 1954) is an American jazz guitarist and composer.

| Pat Metheny | |

|---|---|

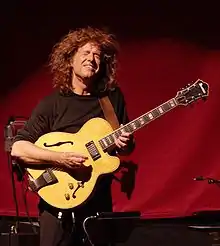

Metheny in 2010 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Patrick Bruce Metheny |

| Born | August 12, 1954 Lee's Summit, Missouri, U.S. |

| Genres | Jazz, jazz fusion, Latin jazz, progressive jazz |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, composer, producer |

| Instruments | Guitar |

| Years active | 1974–present |

| Labels | ECM, Geffen, Warner, Nonesuch |

| Associated acts | Gary Burton, Jaco Pastorius, Pat Metheny Group, Lyle Mays, Steve Rodby, Charlie Haden, Antonio Sánchez |

| Website | www |

He is the leader of the Pat Metheny Group and is also involved in duets, solo works, and other side projects. His style incorporates elements of progressive and contemporary jazz, Latin jazz, and jazz fusion.[1] Metheny has three gold albums and 20 Grammy Awards[2][3] and is the only person to win Grammys in 10 categories. He is the brother of jazz flugelhornist Mike Metheny.

Biography

Early years and education

Metheny was born in Lee's Summit, Missouri. His father Dave played trumpet, his mother Lois sang, and his maternal grandfather Delmar was a professional trumpeter.[4][5] Metheny's first instrument was trumpet, which he was taught by his brother, Mike. His brother, father, and grandfather played trios together at home. His parents were fans of Glenn Miller and swing music. They took Metheny to concerts to hear Clark Terry and Doc Severinsen, but they had little respect for guitar. Metheny's interest in guitar increased around 1964 when he saw the Beatles perform on TV. For his 12th birthday, his parents allowed him to buy a guitar, which was a Gibson ES-140 3/4.[6]

Metheny's life changed after hearing the album Four & More by Miles Davis. Soon after, he was captivated by Wes Montgomery's album Smokin' at the Half Note which was released in 1965. He cites the Beatles, Miles Davis, and Wes Montgomery as having the biggest impact on his music.[6]

When he was 15, he won a scholarship from Down Beat magazine to a one-week jazz camp where he was mentored by guitarist Attila Zoller, who then invited Metheny to New York City to see guitarist Jim Hall and bassist Ron Carter.[7]

While playing at a club in Kansas City, he was approached by Bill Lee, a dean at the University of Miami, and offered a scholarship. After less than a week at college, Metheny realized that playing guitar all day during his teens had left him unprepared for classes. He admitted this to Lee, who offered him a job to teach instead, as the school had recently introduced electric guitar as a course of study.[6]

He moved to Boston to teach at the Berklee College of Music with jazz vibraphonist Gary Burton[7] and established a reputation as a prodigy.[8]

Debut album

In 1974 he appeared on an album unofficially titled Jaco with pianist Paul Bley, bassist Jaco Pastorius, and drummer Bruce Ditmas for Carol Goss's Improvising Artists label. But he was unaware that he was being recorded. During the next year, he joined Gary Burton's band with guitarist Mick Goodrick.

Metheny released his debut album, Bright Size Life (ECM, 1976) with Jaco Pastorius on bass guitar and Bob Moses on drums. His next album, Watercolors (ECM, 1977), was the first time he recorded with pianist Lyle Mays, who became his most frequent collaborator. The album also featured Danny Gottlieb, who became the drummer for the first version of the Pat Metheny Group.[9] With Metheny, Mays, and Gottlieb, the fourth member was bassist Mark Egan when the album Pat Metheny Group (ECM, 1978) was released.

Pat Metheny Group

When Pat Metheny Group (ECM, 1978) was released, the Group was a quartet comprising, besides Metheny, Danny Gottlieb on drums, Mark Egan on bass, and Lyle Mays on piano, autoharp and synthesizer. All but Egan had played on Metheny's album Watercolors (ECM, 1977), recorded a year before the first Group album.[6]

The second Group album, American Garage (ECM, 1979), reached number 1 on the Billboard Jazz chart and crossed over onto the pop charts. From 1982 to 1985, the Pat Metheny Group released Offramp (ECM, 1982), a live album, Travels (ECM, 1983), First Circle (ECM, 1984), and The Falcon and the Snowman (EMI, 1985), a soundtrack album for the movie of the same name in which they collaborated on the single "This Is Not America" with David Bowie. The song reached number 14 in the British Top 40 in 1985 and number 32 in the U.S.[10]

Offramp marked the first appearance of bassist Steve Rodby (replacing Egan) and a Brazilian guest artist, Nana Vasconcelos, on percussion and wordless vocals. On First Circle, Argentinian singer and multi-instrumentalist Pedro Aznar joined the group as drummer Paul Wertico replaced Gottlieb. Both Rodby and Wertico were members of the Simon and Bard Group at the time and had played in Simon-Bard in Chicago before joining Metheny.

First Circle was Metheny's last album with ECM; he had been a key artist for the label but left following disagreements with the label's founder, Manfred Eicher.[11]

Still Life (Talking) (Geffen, 1987) featured new Group members trumpeter Mark Ledford, vocalist David Blamires, and percussionist Armando Marçal. Aznar returned for vocals and guitar on Letter from Home (Geffen, 1989).

During this period the Steppenwolf Theater Company of Chicago featured compositions by Metheny and Mays for their production of Lyle Kessler's play Orphans, where it has remained special optional music for all productions of the play around the world since.

Metheny then again delved into solo and band projects, and four years went by before the release of the next Group record, a live album titled The Road to You (Geffen, 1993), which featured tracks from the two Geffen studio albums among new tunes. The group integrated new instrumentation and technologies into its work, notably Mays' use of synthesizers.

Metheny and Mays themselves refer to the next three Pat Metheny Group releases as a triptych: We Live Here (Geffen, 1995), Quartet (Geffen, 1996), and Imaginary Day (Warner Bros., 1997). Moving away from the Latin style which had dominated the releases of the previous ten years, these albums included experiments with sequenced synthetic drums on one track, free-form improvisation on acoustic instruments, and symphonic signatures, blues, and sonata schemes.

With Speaking of Now (Warner Bros., 2002), new Group members were added: drummer Antonio Sánchez from Mexico City, trumpeter Cuong Vu from Vietnam, and bassist, vocalist, guitarist, and percussionist Richard Bona from Cameroon.

The Way Up (Nonesuch, 2005) consists of one 68-minute-long piece (split into four sections for CD navigation) based on a pair of three-note kernels: The opening B, A#, F# and the derived B, A, F#. On The Way Up, harmonica player Grégoire Maret from Switzerland was introduced as a new group member, while Bona contributed as a guest musician.

Side projects

Outside the Group, Metheny has shown different sides of his musical personality. He made the album Orchestrion (Nonesuch, 2010) with elaborate, custom mechanical instruments, allowing one person to compose and perform as a one-person orchestra. By contrast, his album Secret Story (Geffen, 1992) used orchestral arrangements found more often in movie soundtracks, such as his own The Falcon and the Snowman (EMI, 1985) and A Map of the World (Warner Bros., 1999). His solo acoustic guitar albums include New Chautauqua (ECM, 1979), One Quiet Night (Warner Bros., 2003), and What's It All About (Nonesuch, 2011). He explored the fringes of the avant-garde on Zero Tolerance for Silence (Geffen, 1994). This, too, was an album of solo guitar, but it was electric guitar, and to many fans and critics it was simply noise. Metheny had ventured into the avant-garde before on 80/81 (ECM, 1980), Song X (Geffen, 1986) with Ornette Coleman, and The Sign of Four with Derek Bailey (Knitting Factory Works, 1997).

In 1997, Metheny recorded with bassist Marc Johnson on Johnson's release The Sound of Summer Running (Verve, 1998). The next year, he recorded a guitar duet with Jim Hall (Telarc, 1999), whose work has strongly influenced Metheny's. He collaborated with Polish jazz and folk singer Anna Maria Jopek on Upojenie (Warner Poland, 2002) and Bruce Hornsby on Hot House (RCA, 2005).

He recorded on albums by his older brother, Mike Metheny, a jazz trumpeter, among them Day In – Night Out (1986) and Close Enough for Love (2001).[12][13]

The long list of his collaborators includes Lyle Mays, Bill Frisell, Billy Higgins, Brad Mehldau, Charlie Haden, Chick Corea, Dave Holland, Dewey Redman, Eberhard Weber, Herbie Hancock, Jack DeJohnette, Jaco Pastorius, Jim Hall, John Scofield, Joni Mitchell, Joshua Redman, Marc Johnson, Michael Brecker, Mick Goodrick, Roy Haynes, Steve Swallow, and Tony Williams.[14]

Unity Band

In 2012, he formed the Unity Band with Antonio Sánchez on drums, Ben Williams on bass and Chris Potter on saxophone. This ensemble toured Europe and the U.S. during the latter half of the year. In 2013, as an extension of the Unity Band project, Metheny announced the formation of the Pat Metheny Unity Group, with the addition of the Italian multi-instrumentalist Giulio Carmassi.

Influences

As a young guitarist, Metheny tried to sound like Wes Montgomery, but when he was 14 or 15, he decided it was disrespectful to imitate him.[15] In the liner notes on the 2-disc Montgomery compilation Impressions: The Verve Jazz Sides, Metheny is quoted as saying, "Smokin' at the Half Note is the absolute greatest jazz-guitar album ever made. It is also the record that taught me how to play."

Ornette Coleman's 1968 album New York Is Now! inspired Metheny to find his own direction.[16] He has recorded Coleman's compositions on a number of albums, starting with a medley of "Round Trip" and "Broadway Blues" on his debut album, Bright Size Life (1976). He worked extensively with Coleman's collaborators, such as Charlie Haden, Dewey Redman, and Billy Higgins, and he recorded the album Song X (1986) with Coleman and toured with him.

Metheny made three albums on ECM with Brazilian vocalist and percussionist Naná Vasconcelos. He lived in Brazil from the late 1980s to the early 1990s and performed with several local musicians, such as Milton Nascimento and Toninho Horta. He played with Antônio Carlos Jobim as a tribute, in a live performance in Carnegie Hall Salutes The Jazz Masters: Verve 50th Anniversary.

He is also a fan of several pop music artists, especially singer/songwriters including James Taylor (after whom he named the song "James" on Offramp); Bruce Hornsby, Cheap Trick, and Joni Mitchell, with whom he performed on her Shadows and Light (Asylum/Elektra, 1980) live tour. Metheny is also fond of Buckethead's music. He also worked with, sponsored or helped to make recordings of singer/songwriters from all over the world, such as Pedro Aznar (Argentina), Akiko Yano (Japan), David Bowie (UK), Silje Nergaard (Norway), Noa (Israel), and Anna Maria Jopek (Poland).[17]

Two of Metheny's albums, The Way Up (2005) and Orchestrion (2010), show the influence of American minimalist composer Steve Reich and use similar rhythmic figures structured around pulse. Metheny recorded Reich's composition "Electric Counterpoint" on Reich's album Different Trains (Nonesuch, 1987).

Guitars

Pikasso

Metheny plays a custom-made 42-string Pikasso I created by Canadian luthier Linda Manzer. He plays it on "Into the Dream" and on the albums Quartet (1996), Imaginary Day (1997), Jim Hall & Pat Metheny (1999), Trio → Live (Warner Bros., 2000), and the Speaking of Now Live and Imaginary Day Live DVDs. Metheny has used the guitar in his guest appearances on other artists' albums. He used the Pikasso on Metheny/Mehldau Quartet (Nonesuch, 2007), his second collaboration with pianist Brad Mehldau and his trio sidemen Larry Grenadier and Jeff Ballard; the Pikasso is featured on Metheny's composition "The Sound of Water". Manzer has made many acoustic guitars for Metheny, including a mini guitar, an acoustic sitar guitar, and the baritone guitar, which Metheny used for the recording of One Quiet Night (2003).

Guitar synthesizer

Metheny was one of the first jazz guitarists to use the Roland GR-300 Guitar Synthesizer. He commented, "you have to stop thinking about it as a guitar, because it no longer is a guitar." He approaches it as if he were a horn player, and he prefers the "high trumpet" sound of the instrument.[18] One of the "patches" that he has often used is on Roland's JV-80 "Vintage Synth" expansion card, titled "Pat's GR-300".. In addition to the Roland, he uses a Synclavier controller.[18]

Six-string and twelve-string electric

Metheny was an early proponent of the twelve-string guitar in jazz. During his 1975 tour with the Gary Burton "Quartet" (five people, including Metheny), he primarily played electric twelve-string guitar against the six-string work of resident guitarist Mick Goodrick.[19]

Prior to Metheny, Pat Martino had used the electric twelve-string guitar on a studio album, Desperado, and John McLaughlin had used a double-neck electric guitar with the Mahavishnu Orchestra. Ralph Towner was perhaps the first[20] to use acoustic twelve-string guitar extensively in jazz ("The Moors", from Weather Report's I Sing the Body Electric, Columbia, 1972), and Larry Coryell and Philip Catherine made extensive use of acoustic twelve string in alternate tunings at the 1975 Montreux Jazz Festival, later releasing some of the material on their 1976 Twin House album.

Metheny used a twelve-string guitar on his debut album, Bright Size Life (1976), including alternate tuning on "Sirabhorn", and on later albums ("San Lorenzo", from Pat Metheny Group and Travels).

Semi-acoustic guitars

At the age of 12, Metheny bought a natural finish Gibson ES-175 that he played throughout his early career, until it was retired in 1995.[21] After his first tour of Japan in 1978, he began an association with Ibanez guitars, who have since produced a range of PM signature models.[22]

Material loss

On June 25, 2019, The New York Times Magazine listed Pat Metheny among hundreds of artists whose material was reportedly destroyed in the 2008 Universal Studios fire.[23]

Awards and honors

- Only artist to win Grammy Awards in ten different categories[24]

- Down Beat Hall of Fame, 2013

- Miles Davis Award, Montreal International Jazz Festival, 1995

- Orville H. Gibson Award, 1996

- Honorary Doctorate of Music from Berklee College of Music, 1996[25]

- Guitarist of the Year, Down Beat Readers' Poll, 1983, 1986–'91, 2007–2016

- Best Jazz Guitarist, Guitar Player magazine, 1982, '83, '86

- Best Jazz Guitarist, Guitar Player magazine Readers' Poll, '84, '85, 2009

- Best Acoustic Guitarist, Acoustic Guitar magazine Readers' Poll, 2009

- Echo Award for Best Guitar Instrumentalist – International for TAP: John Zorn's Book of Angels Vol. 20, 2014

- Echo Award, International Ensemble of the Year, Kin, 2015

- Missouri Music Hall of Fame, 2016

- Lifetime Achievement Award, JazzFM, 2018

- Elected into Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 2018

- 2018 NEA Jazz Masters, 2017[26][27]

- Honorary Doctorate of Music from McGill University, 2019

Grammy Awards

| Year | Category | Title | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Best Jazz Instrumental Album | Unity Band | With the Unity Band |

| 2012 | Best New Age Album | What's It All About | |

| 2008 | Best Jazz Instrumental Album | Pilgrimage | (Won as producer) |

| 2006 | Best Contemporary Jazz Album | The Way Up | Pat Metheny Group |

| 2004 | Best New Age Album | One Quiet Night | |

| 2003 | Best Contemporary Jazz Album | Speaking of Now | Pat Metheny Group |

| 2001 | Best Jazz Instrumental Solo | "(Go) Get It" | (Won as soloist) |

| 2000 | Best Jazz Instrumental Performance | Like Minds | With Chick Corea, Dave Holland, Gary Burton, Roy Haynes |

| 1999 | Best Rock Instrumental Performance | "The Roots of Coincidence" | Pat Metheny Group |

| 1999 | Best Contemporary Jazz Performance | Imaginary Day | Pat Metheny Group |

| 1998 | Best Jazz Instrumental Performance | Beyond the Missouri Sky | With Charlie Haden |

| 1996 | Best Contemporary Jazz Performance | We Live Here | Pat Metheny Group |

| 1994 | Best Contemporary Jazz Performance | The Road to You | Pat Metheny Group |

| 1993 | Best Contemporary Jazz Performance | Secret Story | |

| 1991 | Best Instrumental Composition | "Change of Heart" | (Won as composer) |

| 1989 | Best Jazz Fusion Performance | Letter from Home | Pat Metheny Group |

| 1988 | Best Jazz Fusion Performance | Still Life (Talking) | Pat Metheny Group |

| 1985 | Best Jazz Fusion Performance | First Circle | Pat Metheny Group |

| 1984 | Best Jazz Fusion Performance | Travels | Pat Metheny Group |

| 1983 | Best Jazz Fusion Performance | Offramp | Pat Metheny Group |

Source:[28]

Discography

- Bright Size Life (ECM, 1976)

- Watercolors (ECM, 1977)

- Pat Metheny Group (ECM, 1978)

- New Chautauqua (ECM, 1979)

- American Garage (ECM, 1979)

- 80/81 (ECM, 1980)

- As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls (ECM, 1981) with Lyle Mays

- Offramp (ECM, 1982)

- Travels (ECM, 1983)

- Rejoicing (ECM, 1984)

- First Circle (ECM, 1984)

- The Falcon and the Snowman (EMI, 1985)

- Song X (Geffen, 1986) with Ornette Coleman

- Still Life (Talking) (Geffen, 1987)

- Letter from Home (Geffen, 1989)

- Question and Answer (Geffen, 1990)

- Secret Story (Geffen, 1992)

- The Road to You (Geffen, 1993)

- Zero Tolerance for Silence (Geffen, 1994)

- I Can See Your House from Here (Blue Note, 1994) with John Scofield

- We Live Here (Geffen, 1995)

- Quartet (Geffen, 1996)

- Passaggio per il paradiso (MCA, 1996)

- Beyond the Missouri Sky (Short Stories) (Verve, 1997) with Charlie Haden

- Imaginary Day (Warner Bros., 1997)

- Like Minds (Concord Jazz, 1998)

- Jim Hall & Pat Metheny (Telarc, 1999)

- A Map of the World (Warner Bros., 1999)

- Trio 99 → 00 (Warner Bros., 2000)

- Trio → Live (Warner Bros., 2000)

- Speaking of Now (Warner Bros., 2002)

- One Quiet Night (Warner Bros., 2003)

- The Way Up (Nonesuch, 2005)

- Metheny/Mehldau (Nonesuch, 2006)

- Metheny Mehldau Quartet (Nonesuch, 2007)

- Day Trip[6]:155–158(Nonesuch, 2008)

- Tokyo Day Trip (Nonesuch, 2008)

- Upojenie (Nonesuch, 2008) with Anna Maria Jopek

- Quartet Live (Concord Jazz, 2009) with Gary Burton

- Orchestrion (Nonesuch, 2010)

- What's It All About (Nonesuch, 2011)

- Unity Band (Nonesuch, 2012) with Chris Potter

- The Orchestrion Project (Nonesuch, 2013)

- Tap: Book of Angels Volume 20 (Tzadik/Nonesuch, 2013)

- KIN (←→) (Nonesuch, 2014)

- Hommage à Eberhard Weber (ECM, 2015)

- The Unity Sessions (Nonesuch, 2016)

- Cuong Vu Trio Meets Pat Metheny (Nonesuch, 2016)[29]

- From This Place (Nonesuch, 2020)

- Road to the Sun (Modern Recordings, 2021)

References

- Yanow, Scott (2010). "Pat Metheny". allmusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Past Winners Search". GRAMMY.com. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- Moser, John J. "After 40 years at the top of jazz, guitarist Pat Metheny turns 'eye' to working with others on their way up". mcall.com. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- "Lois Hansen Metheny's Obituary on Kansas City Star". Kansas City Star. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Niesel, Jeff. "In Advance of Next Week's Show at the Kent Stage, Pat Metheny Talks About His Side-Eye Side Project". Cleveland Scene. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- Niles, Richard (2009). The Pat Metheny Interviews: The Inner Workings of His Creativity Revealed. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Books. pp. 4–23. ISBN 978-1-4234-7469-2.

- Taylor, B. Kimberly (1999). "Pat Metheny 2002". Encyclopedia.com. HighBeam Research, Inc. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- Chinen, Nate (January 28, 2010). "19th-Century Concept, With a Few Upgrades". New York Times. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- Ginell, Richard. "Watercolors". AllMusic. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- Molanphy, Chris (January 12, 2016). "David Bowie's Blackstar Could Be His First No. 1 Album. We Can Do This, America". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- Aledort, Andy (Spring 1990). "Pat Metheny: Straight Ahead". Guitar Extra!. p. 62.

- "Mike Metheny official website". Mikemetheny.com. June 7, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- "Metheny Music Foundation, Inc". Methenymusicfoundation.org. July 23, 2010. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- Forte, Dan (December 1, 2016). "Pat Metheny: The Jazz Guitar Prodigy at 60". Vintage Guitar. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- Ratliff, Ben (February 25, 2005). "Pat Metheny: An Idealist Reconnects With His Mentors". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- Jeff Kitts and Brad Tolinski, Eds. (October 1, 2002). Guitar World Presents 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-634-04619-3.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Pat Metheny". Pat Metheny. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- Webb, Nicholas (May 1985). "Interview with Pat Metheny". Guitarist.

- Cooke, Mervyn (2017). Pat Metheny: the ECM years, 1975-1984. Oxford University Press. p. 38.

- Cline, Nels (August 2017). "Focused: An appreciation of the genre-bending guitar work of Ralph Towner". FretboardJournal.com. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- "Gibson ES-175 – Metheny's". Equipboard, Inc. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- Levy, Adam (March 2001). "Pat Metheny talks trios, tones & technique". Guitar Player Magazine.

- Rosen, Jody (June 25, 2019). "Here Are Hundreds More Artists Whose Tapes Were Destroyed in the UMG Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- "Pat Metheny: Awards". Pat Metheny. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- "Pat Metheny : Bio". Patmetheny.com. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- "Pat Metheny Named 2018 NEA Jazz Master". Nonesuch Records Official Website. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- "Pat Metheny". NEA. June 12, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- "Past Winners Search". GRAMMY.com. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- "Pat Metheny | Album Discography". AllMusic. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

Further reading

- Florin, Ludovic, and Ségala, Pascal. Pat Metheny, Artiste multiplunique (in French). Éditions du Layeur, 2017. (ISBN 978-2-915126-35-8)

- Goins, Wayne E. Emotional Response to Music: Pat Metheny's Secret Story. Edwin Mellen Press, 2001.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pat Metheny. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Pat Metheny |

- Official site

- Pat Metheny discography at Discogs

- Pat Metheny at AllMusic

- Pat Metheny at IMDb

- Pat Metheny's guitar rig

- Pat Metheny's artist file at the Montreal International Jazz Festival's website