Differentiable function

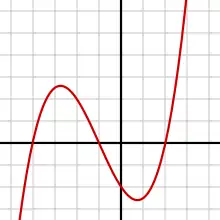

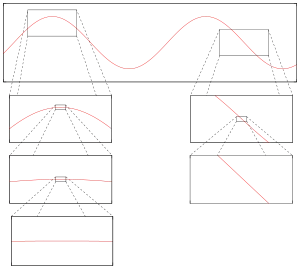

In calculus (a branch of mathematics), a differentiable function of one real variable is a function whose derivative exists at each point in its domain. In other words, the graph of a differentiable function has a non-vertical tangent line at each interior point in its domain. A differentiable function is smooth (the function is locally well approximated as a linear function at each interior point) and does not contain any break, angle, or cusp.

More generally, for x0 as an interior point in the domain of a function f, then f is said to be differentiable at x0 if and only if the derivative f ′(x0) exists. In other words, the graph of f has a non-vertical tangent line at the point (x0, f(x0)). The function f is also called locally linear at x0 as it is well approximated by a linear function near this point.

Differentiability of real functions of one variable

A function , defined on an open set , is differentiable at if the derivative

exists. This implies that the function is continuous at a.

This function f is differentiable on U if it is differentiable at every point of U. In this case, the derivative of f is thus a function from U into

A differentiable function is necessarily continuous (at every point where it is differentiable). It is continuously differentiable if its derivative is also a continuous function.

Differentiability and continuity

.svg.png.webp)

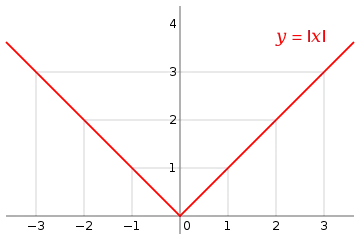

If f is differentiable at a point x0, then f must also be continuous at x0. In particular, any differentiable function must be continuous at every point in its domain. The converse does not hold: a continuous function need not be differentiable. For example, a function with a bend, cusp, or vertical tangent may be continuous, but fails to be differentiable at the location of the anomaly.

Most functions that occur in practice have derivatives at all points or at almost every point. However, a result of Stefan Banach states that the set of functions that have a derivative at some point is a meagre set in the space of all continuous functions.[1] Informally, this means that differentiable functions are very atypical among continuous functions. The first known example of a function that is continuous everywhere but differentiable nowhere is the Weierstrass function.

Differentiability classes

.svg.png.webp)

A function f is said to be continuously differentiable if the derivative f′(x) exists and is itself a continuous function. Although the derivative of a differentiable function never has a jump discontinuity, it is possible for the derivative to have an essential discontinuity. For example, the function

is differentiable at 0, since

exists. However, for x ≠ 0, differentiation rules imply

which has no limit as x → 0. Nevertheless, Darboux's theorem implies that the derivative of any function satisfies the conclusion of the intermediate value theorem.

Continuously differentiable functions are sometimes said to be of class C1. A function is of class C2 if the first and second derivative of the function both exist and are continuous. More generally, a function is said to be of class Ck if the first k derivatives f′(x), f′′(x), ..., f (k)(x) all exist and are continuous. If derivatives f (n) exist for all positive integers n, the function is smooth or equivalently, of class C∞.

Differentiability in higher dimensions

A function of several real variables f: Rm → Rn is said to be differentiable at a point x0 if there exists a linear map J: Rm → Rn such that

If a function is differentiable at x0, then all of the partial derivatives exist at x0, and the linear map J is given by the Jacobian matrix. A similar formulation of the higher-dimensional derivative is provided by the fundamental increment lemma found in single-variable calculus.

If all the partial derivatives of a function exist in a neighborhood of a point x0 and are continuous at the point x0, then the function is differentiable at that point x0.

However, the existence of the partial derivatives (or even of all the directional derivatives) does not in general guarantee that a function is differentiable at a point. For example, the function f: R2 → R defined by

is not differentiable at (0, 0), but all of the partial derivatives and directional derivatives exist at this point. For a continuous example, the function

is not differentiable at (0, 0), but again all of the partial derivatives and directional derivatives exist.

Differentiability in complex analysis

In complex analysis, complex-differentiability is defined using the same definition as single-variable real functions. This is allowed by the possibility of dividing complex numbers. So, a function is said to be differentiable at when

Although this definition looks similar to the differentiability of single-variable real functions, it is however a more restrictive condition. A function , that is complex-differentiable at a point is automatically differentiable at that point, when viewed as a function . This is because the complex-differentiability implies that

However, a function can be differentiable as a multi-variable function, while not being complex-differentiable. For example, is differentiable at every point, viewed as the 2-variable real function , but it is not complex-differentiable at any point.

Any function that is complex-differentiable in a neighborhood of a point is called holomorphic at that point. Such a function is necessarily infinitely differentiable, and in fact analytic.

Differentiable functions on manifolds

If M is a differentiable manifold, a real or complex-valued function f on M is said to be differentiable at a point p if it is differentiable with respect to some (or any) coordinate chart defined around p. More generally, if M and N are differentiable manifolds, a function f: M → N is said to be differentiable at a point p if it is differentiable with respect to some (or any) coordinate charts defined around p and f(p).

References

- Banach, S. (1931). "Über die Baire'sche Kategorie gewisser Funktionenmengen". Studia Math. 3 (1): 174–179.. Cited by Hewitt, E; Stromberg, K (1963). Real and abstract analysis. Springer-Verlag. Theorem 17.8.