Dillwyn v Llewelyn

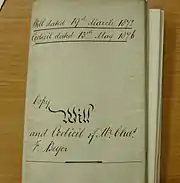

Dillwyn v Llewelyn [1862] is an 'English' land, probate and contract law case which established an example of proprietary estoppel at the testator's wish overturning his last Will and Testament; the case concerned land in Wales demonstrating the united jurisdiction of England and Wales.

| Dillwyn v Llewelyn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | Court of Appeal in Chancery |

| Full case name | Hon. Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn v John Dillwyn Llewelyn |

| Decided | 4 June and 12 July 1862 |

| Citation(s) | [1862] EWHC Ch J67 (1862) 4 De G F & J 517 |

| Case history | |

| Prior action(s) | Appellant (plaintiff in this case) lost by a decree of the Master of the Rolls at first instance (the Court of Chancery) limiting his inheritance to a life interest. |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Lord Westbury, Lord Chancellor |

| Keywords | |

| Contract, proprietary estoppel, law of deeds, required formalities in conveyancing, imperfect gift, variation of wills | |

The sole appellate judge, the Lord Chancellor of England and Wales held: "by virtue of the original gift made by the testator and of the subsequent expenditure by the Plaintiff with the approbation [approval] of the testator, and of the right and obligation resulting therefrom, the Plaintiff is entitled to have a conveyance."

Facts

In 1847 the parties' father (Lewis Weston Dillwyn of Sketty Hall) earlier bequeathed his lands on trust to his widow for life and with a complex remainder so that his younger son, the "plaintiff", would inherit absolutely if he obtained 21 years of age; otherwise charged with annuities (equity partly-released) for certain daughters and thereafter to the defendant (and his heirs).

He later wished to give immediately to the plaintiff (Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn) one of these parcels, his farm at Hendrefoilan near to Sketty Hall, and thought he had done so by signing a memorandum presenting it to him “for the purpose of furnishing himself with a dwelling-house”. The memorandum was not a deed — a proper deed would make it binding to all the world at common law. The younger son, the plaintiff, incurred great expense in building a house on the land. The elder son and father signed and dated the memorandum. Two years later in 1855 the father died and the elder son (John Dillwyn Llewelyn) disputed his younger brother's imperfect title (ownership). The widow, noted photographer, Mary Dillwyn died in 1906 and chose to waive her life interest in the property.

At first instance, Sir John Romilly MR decreed that the claimant was entitled to a life interest (possession for life in the estate in land, worth £14,000).

Judgment

Lord Westbury L.C. on appeal held that the younger son had an incomplete gift and was on the facts entitled to call for a legal conveyance of the whole freehold (fee simple). His reasoning was:[1]

About the rules of the court there can be no controversy. A voluntary agreement will not be completed or assisted by a court of equity, in cases of mere gift. If anything be wanting to complete the title of the donee, a court of equity will not assist him in obtaining it; for a mere donee can have no right to claim more than he has received. But the subsequent acts of the donor may give the donee that right or ground of claim which he did not acquire from the original gift. Thus, if A gives a house to B, but makes no formal conveyance, and the house is afterwards, on the marriage of B, included, with the knowledge of A, in the marriage settlement of B, A would be bound to complete the title of the parties claiming under that settlement. So if A puts B in possession of a piece of land, and tells him, ‘I give it to you that you may build a house on it,’ and B on the strength of that promise, with the knowledge of A, expends a large sum of money in building a house accordingly, I cannot doubt that the donee acquires a right from the subsequent transaction to call on the donor to perform that contract and complete the imperfect donation which was made...

The Master of the Rolls, however, seems to have thought that a question might still remain as to the extent of the estate taken by the donee, and that in this particular case the extent of the donee's interest depended on the terms of the memorandum. I am not of that opinion. The equity of the donee and the estate to be claimed by virtue of it depend on the transaction, that is, on the acts done, and not on the language of the memorandum, except as that shews the purpose and intent of the gift. The estate was given as the site of a dwelling-house to be erected by the son. The ownership of the dwelling-house and the ownership of the estate must be considered as intended to be co-extensive and co-equal. No one builds a house for his own life only, and it is absurd to suppose that it was intended by either party that the house, at the death of the son, should become the property of the father. If, therefore, I am right in the conclusion of law that the subsequent expenditure by the son, with the approbation of the father, supplied a valuable consideration originally wanting, the memorandum signed by the father and son must be thenceforth regarded as an agreement for the soil extending to the fee-simple of the land. In a contract for sale of an estate no words of limitation are necessary to include the fee-simple; but, further, upon the construction of the memorandum itself, taken apart from the subsequent acts, I should be of opinion that it was the plain intention of the testator to vest in the son the absolute ownership of the estate. The only inquiry therefore is, whether the son's expenditure on the faith of the memorandum supplied a valuable consideration and created a binding obligation. On this I have no doubt; and it therefore follows that the intention to give the fee-simple must be performed, and that the decree ought to declare the son the absolute owner of the estate comprised in the memorandum.

I propose, therefore, to vary the decree of the Master of the Rolls, and to declare, by virtue of the original gift made by the testator and of the subsequent expenditure by the Plaintiff with the approbation of the testator, and of the right and obligation resulting therefrom, the Plaintiff is entitled to have a conveyance from the trustees of the testator's will and other parties interested under the same of all their estate and interest under the testator's will in the estate of Hendrefoilan in the pleadings mentioned, and with this declaration refer it to the Judge in Chambers to settle such conveyance accordingly.

See also

- Willmott v Barber (1880) 15 Ch D 96, Fry J, in a court of first instance, said proprietary estoppel requires a mistake about rights, reliance, defendant has knowledge of his own right, know of the claimant's mistaken belief and have encouraged reliance

- Syros Shipping Co SA v Elaghill Trading Co or The Proodos C [1981] 3 All ER 189 applied the doctrine as formulated by Lord Denning when he was a first instance judge in Central London Property Trust Ltd v High Trees House Ltd [1947] KB 130; [1956] 1 All ER 256; 62 TLR 557, KBD[2]

References

- (1862) 4 De G F & J 517, 522

- "Index card Central London Property Trust Ltd v High Trees House Ltd - ICLR".