Disney bomb

The Disney bomb, also known as the Disney Swish,[4] officially the 4500 lb Concrete Piercing/Rocket Assisted bomb was a rocket-assisted bunker buster bomb developed during the Second World War by the British Royal Navy to penetrate hardened concrete targets, such as submarine pens, which could resist conventional free-fall bombs.

| Disney bomb | |

|---|---|

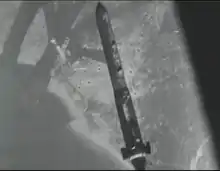

A Disney bomb just after release | |

| Type | Bunker buster bomb |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1945–46 |

| Used by | United States Army Air Forces |

| Wars | World War II |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Edward Terrell |

| Designed | 1943 |

| Manufacturer | Vickers Armstrong[1] |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 4,500 lb (2,000 kg) |

| Length | 16 ft 6 in (5.03 m)[Note 1] |

| Diameter | Body: 15 in (380 mm) Tail 17 in (430 mm) [Note 2] |

| Warhead | Shellite[2] |

| Warhead weight | 500 lb (230 kg)[2] |

Detonation mechanism | Base fuze |

| Propellant | Cordite |

Launch platform | Aircraft |

| Transport | Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, Boeing B-29 Superfortress[3] |

Devised by Royal Navy Captain Edward Terrell, the bomb was fitted with solid-fuel rockets to accelerate its descent, giving it an impact speed of 990 mph (1,590 km/h) — substantially beyond the 750 mph (1,210 km/h) free-fall impact velocity[5] of the 5 tonne Tallboy "earthquake" bomb for comparable purposes.

The Disney could penetrate 16 ft (4.9 m) of solid concrete before detonating. The name is attributed to a propaganda film, Victory Through Air Power, produced by the Walt Disney Studios, that provided the inspiration for the design.

The Disney bomb saw limited use by the United States Army Air Forces in Europe from February to April 1945. Although technically successful, it initially was insufficiently accurate for attacking bunker targets. It was deployed late in the war and had little effect on the Allied bombing campaign against Germany.

Background

During the Second World War, Barnes Wallis developed two large "earthquake" bombs for the Royal Air Force: the five-tonne Tallboy and the ten-tonne Grand Slam, for use against targets too heavily protected to be affected by conventional high explosive bombs.[6]

These enormous weapons were designed to strike close by their target, to penetrate deeply into the earth, and to cause major structural damage by the shock waves transmitted through the ground.[Note 3] In practice, they proved capable of penetrating a significant thickness of concrete if they scored a direct hit, despite not being designed for that purpose by Wallis, who had to work within the accuracy limitations of current bombsights[7] and the resulting low accuracy of the bombings.[8][Note 4]

The Disney bomb, by contrast, was designed from the start to penetrate the thick concrete roofs of fortified bunkers. Whereas the earthquake bomb's target was the bunker itself, the Disney bomb's target was the bunker's contents. To this end, the warhead was composed of an unusually thick steel shell containing a comparatively small amount of explosive.[Note 5] It was much slimmer than was usual for aircraft-dropped bombs, and a cluster of booster rockets accelerated the weapon as it fell. These features accord with Newton's approximation for impact depth and the empirical design equation known as Young's equation that states that the deepest target penetration is achieved by a projectile that is dense, long and thin (i.e. has a large sectional density), and strikes with a high velocity.[9]

Description

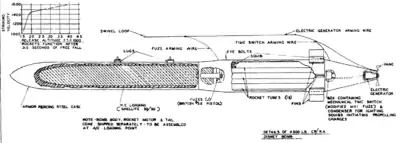

The CP/RA[Note 6] Disney bombs were 16 ft 6 in (5.03 m) long[10] and weighed 4,500 pounds (2,000 kg). The diameter of the body of the bomb was 11 in (280 mm), while the diameter at the tail was 17 in (430 mm).[10] They were composed of three sections.

The forward section was the warhead—an explosive charge of 500 pounds (230 kg) of shellite,[2] contained within an armour-piercing casing of thick steel and fitted with two British No.58 MK I tail Pistol fuzes at the base (i.e. furthest from the nose).[Note 7]

The second section was made up of nineteen rocket motors from the 3-inch Rocket Projectile – essentially metal tubes filled with cordite.[2][11] In the third rear section, a tail cone contained the circuit that ignited the rockets. This was powered by a small generator with a vane spun by the airstream going past the falling bomb. Rocket ignition was controlled either by a time-delay switch,[1] or a barometric switch.[Note 8][12]

There were six small fins at the rear of the bomb for stabilisation. The bomb was suspended from the aircraft by two weight-bearing lugs. Three arming wires also connected the bomb and the aircraft; as the bomb dropped, a brief tug from the wires would arm the warhead fuzes and the rocket-ignition circuit, and unlock the electrical generator, allowing it to spin freely.[2]

- Diagram and close-up of a Disney bomb

For accuracy, the bombs had to be dropped precisely from a pre-determined height, usually 20,000 feet (6,100 m).[14] They would free-fall for around 30 seconds until, at 5,000 feet (1,500 m), the rockets were ignited, causing the tail section to be expelled.[14] The rocket burn lasted for three seconds[15] and added 300 feet per second (91 m/s) to the bomb's speed, giving a final impact speed of 1,450 feet per second (440 m/s), equivalent to 990 miles per hour (1,590 km/h) or[15] approximately Mach 1.29.[Note 9] Post-war tests demonstrated the bombs were able to penetrate a 14-foot-8-inch (4.47 m) thick concrete roof,[16] with the predicted (but untested) ability to penetrate 16 feet 8 inches (5.08 m) of concrete.[16]

Development and testing

According to an anecdote, the idea arose after a group of Royal Navy officers saw a similar, but fictional, bomb depicted in the 1943 Walt Disney animated propaganda film Victory Through Air Power,[Note 10] and the name Disney was consequently given to the weapon.[17] The Royal Navy developed the bomb[18] even though the Fleet Air Arm operated no aircraft capable of carrying it.[Note 11] The navy was interested in a concrete-penetrating weapon due to the German navy's extensive use of fortified submarine pens to protect their U-boats and E-boats from air attack while docked.

The Disney Bomb was devised by a British naval officer, Captain Edward Terrell[19] of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, who served in the Directorate of Miscellaneous Weapons Development.[20] Before the war, he had been a lawyer and the Recorder of Newbury.[21] However, he was also an enthusiastic inventor and had filed several patents pre-war, including ones for a vegetable peeling knife[22] and a bottle for fountain pen ink.[23]

The bomb's development began in September 1943. Although there was support for the idea at the highest levels within the Admiralty, production of the weapon would have to come under the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP). The Road Research Laboratory[Note 12] provided theoretical formula for penetration from US data on the performance of 15-inch (381 mm) shells against reinforced concrete, and the Chief Engineer of Armament Development at Fort Halstead prepared a preliminary design to present to the MAP.

In the face of opposition, the First Sea Lord prepared a memorandum for the Anti-U-Boat Committee, of which Churchill was the Chairman. Terrell visited Churchill's scientific adviser Lord Cherwell to convince him that it was feasible technically. Due to the Prime Minister's absence through illness, it was not until January 1944 that Churchill expressed a desire that the bomb should be considered by the committee. Due to the number of departments involved there were meetings involving large numbers of technicians and scientists to confirm the technical feasibility.[24]

Terrell received support through the Air Technical Section of the USAAC, and was able to show the Admiralty a mockup under the wing of a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. The Air Ministry was still opposed to its development on several technical grounds, and it took a meeting of the War Cabinet in May, which Terrell attended, to decide in its favour, giving it "P plus" priority. As a side effect the meeting focused attention on the issue of the U-boat shelters, and the RAF were directed to make attacks on them, dropping 26 Tallboys in August that year.[25]

Despite being a British weapon, Disneys were used only by the United States Army Air Force, with the bombs becoming a joint project between the American Eighth Air Force and the British Royal Navy; they were never used by RAF Bomber Command.[Note 13][Note 14] The 92nd Bombardment Group was initially tasked with their use. The bombs were also dropped by the 305th Bombardment Group and 306th Bombardment Group. The 94th Bombardment Group prepared to use the bombs, but flew no operations with them before the war in Europe ended.[26]

The B-17 Flying Fortresses operated by these units carried the bombs in pairs; one was slung under each wing, as they were too long to be carried in the B-17's bomb bay. The Disneys were carried from the same external mounting used for the Aeronca GB-1 glide bomb.[27] Cameras were also fitted to the aircraft so the bombs' trajectory and effect could be recorded.[28]

Testing of the Disney bombs began in early 1945. Bombs were initially dropped on a bombing range near Southampton to photographically record their trajectory and calibrate bombsights. This was necessary as the flight-path of a rocket-accelerated bomb differed considerably from that of a free–falling bomb.[12] Test drops were then conducted on the Watten bunker, German codename Kraftwerk Nord West (now known as the Blockhaus d'Éperlecques), a huge German concrete bunker near Watten in northern France. This was ideal for the purpose as the area had been captured by Allied forces in September 1944, so damage to the structure could be inspected after bomb tests.[12] Four bombs, carried by two B-17s, were used and two hits scored on the target. The resultant damage was considered satisfactory by Royal Navy observers on the ground.[12]

Combat

The first Disney attack was against the port of IJmuiden, Netherlands.[29][30] This was the site of two separate fortified pens used by the German navy to house their Schnellboote (fast torpedo boats, known to the Allies as "E-boats")[31] and Biber midget submarines.[32] The older structure, codename Schnellbootbunker AY (SBB1), was protected by a 10-foot (3.0 m) thick concrete roof.[31] The newer one, codename Schnellbootbunker BY (SBB2), had 10–12 feet (3.0–3.7 m) of concrete, with a further 2–4-foot (0.61–1.22 m) layer separated by an air–gap.[Note 15][32]

The E-boats laid up in the shelters during the day, safe from air–attack, and put to sea under cover of night to attack Allied shipping.[31] The pens were priority targets as the torpedo boats they protected were a considerable threat to the supply lines serving Allied forces in western Europe. Since August 1944, the two bunkers had been attacked four times by No. 9 Squadron and No. 617 Squadron of the RAF, with a total of 53 of the five–ton, Tallboy earthquake bombs.[33][34] There had been numerous other attacks from bombers carrying smaller, conventional bombs.

Nine aircraft of the 92nd Bomb Group, carrying 18 Disneys, attacked Schnellbootbunker BY (SBB2) on 10 February 1945.[35] Royal Navy intelligence learned the concrete had been penetrated, but the pens had been empty at the time of the attack.[12] The 92nd therefore carried out an attack on the SBB1 pen, again with nine aircraft,[36] on 14 March.[37]

On 30 March 36 aircraft from the US Eighth Air Force, including 12 from the 92nd Bomb Group,[38] attacked the Valentin submarine pens, a massive, bomb–hardened concrete shelter under construction at the small port of Farge, near Bremen in Germany (location: 53°13′00″N 8°30′15″E) with Disney bombs. The shelter was nearing completion and was to be a factory for the assembly of Type XXI U-boats.[39] Construction had been under way since 1943, using the forced labour of 10,000 concentration–camp prisoners, prisoners–of–war and foreign civilians (Fremdarbeiter) who suffered a high death rate because of the horrific conditions they worked under.[40]

Valentin's 4.5-metre (15 ft)-thick roof had already been damaged by two 10-ton Grand Slam bombs dropped by the RAF three days earlier, on 27 March.[41] During the Eighth Air Force attack more than sixty Disneys were launched, but only one hit the target, with little effect, although installations around the bunker received considerable damage.[42] After the bombing the Germans made limited attempts to carry out repairs before abandoning the complex; the area was captured by the British Army four weeks later.[42]

On 4 April 1945, 24 B-17s attacked fortified targets in Hamburg.[43] The target was obscured by cloud so radar guidance was used to launch the bombs. A further mission in May 1945 was cancelled.[44] A total of 158 bombs were dropped before the end of the war.[20] No aircraft or aircrew were lost during the four Disney combat missions.[45]

Post-war development

In June 1945 the Air Council[Note 16] wrote to the Lords of the Admiralty expressing "their appreciation" of the work that had been done on the "rocket bomb".[47] The RAF initiated bombing tests of the Disney in June 1945, using the Watten bunker as a target.[48] The actual bombing was carried by the US 8th Air Force on behalf of the RAF.[49] However, Watten proved too small to be a satisfactory target,[48] and the French objected to continued bombing of their territory in peace-time.[50]

Further testing took place as part of Project Ruby.[51] This was a 1946 joint Anglo-American programme to test a range of concrete penetrating bombs against a wartime German bunker on the small island of Heligoland and the Valentin submarine pens. Bombs tested included the Tallboy and the Grand Slam (both British and US-made versions), the American 22,000-pound (10,000 kg) Amazon and 2,000-pound (910 kg) M103 SAP bombs, and the Disney. The bombs dropped on Valentin were inert, as the objective was not to observe the effects of bomb explosions, but rather to test concrete penetration and the strength of the bomb casings.[48] Also, with the restoration of peace, the safety of civilians living around Valentin had become a consideration.[49]

Heligoland was uninhabited at the time as its small population had been evacuated during the war. It was the site of a U-boat pen with a 10-foot (3.0 m) thick roof. This was used to test bombs loaded with explosive but with inert detonators, to make sure the explosives used would not themselves detonate immediately upon impact with the target, before penetrating it.[49]

This peace-time testing of the bomb was far more extensive than could be carried out prior to its wartime deployment. A total of 76 Disneys were dropped on Heligoland, loaded with a variety of explosive charges, composed of shellite, RDX, TNT or Picratol.[52] Thirty-four Disneys were dropped on Valentin, 12 with the rockets inactivated[53] and 22 with the rockets firing.[15] A further four had been previously dropped on a bomb range at Orford Ness to test their accuracy, and to make sure none would land outside the safety exclusion zone that was set up around Valentin during the trials.[15]

The penetration performance (14 feet 8 inches (4.47 m) of concrete) of the Disney was found to be satisfactory, with a predicted maximum penetration of 16 ft 8 in (5.08 m).[16] One of the bombs penetrated both Valentin's concrete roof, and its 3-foot (0.91 m) thick concrete floor, coming to rest completely buried in the sand under structure's foundations.[54] However, there were problems with the bombs. The reliability of the rocket booster ignition was considered unsatisfactory,[55] with a failure rate of around 37% during the trials.[15] Also, some bombs broke up on impact with the target due to flaws in the steel casing, and bombs struck at an angle, increasing the effective thickness of concrete they had to penetrate. Furthermore, it was noted that the warhead of the bomb was comparatively small,[55] so a very large bunker complex such as Valentin would have required many penetrating hits to be sure of destroying all the contents.

In comparison, the effective concrete penetration of the Tallboy and Grand Slams was similar to the Disney (around 14 feet (4.3 m)). Although these bombs directly penetrated only around 7 feet (2.1 metres) of concrete, the remaining thickness was blown in by the detonation of the bombs' enormous explosive charge. The roof of Valentin had been penetrated by two Grand Slams before the war ended but, as there was no detonation inside the bunker, there was little damage to the complex aside from the large holes in the roof; post-war examination revealed installations inside the bunker remained comparatively unscathed.[42] The conclusion of Project Ruby was that none of the bombs tested was completely suitable, and the development of a new concrete–penetrating bomb was recommended.[56] The Disney's rocket-assist was viewed as a worthwhile feature that should be incorporated into any new bomb designs[57] because target penetration increases with strike velocity, although penetration increases only marginally from drop altitudes higher than 20,000 feet (6,100 m).[58]

On 27 January 2009 the body of an inactive Disney bomb, with its 500-pound (230 kg) explosive charge, was extracted from the roof of Watten bunker (by now a private museum), where it had embedded itself during one of the 1945 test-drops. The bomb was transferred to the ammunition depot at La Geule d'Ours, two kilometres from the centre of Vimy, where recovered chemical ammunition and equipment from the First World War is processed.[20][59]

See also

- German Rocket Propelled Bombs

- Kinetic energy penetrator, type of ammunition without explosives that uses kinetic energy to penetrate the target.

- Matra Durandal, post–war, French, unguided rocket-boosted bomb, designed for use an anti–runway bomb.

- Massive Ordnance Penetrator, a 2000s bunker buster weapon of similar design and purpose.

Notes

- Spillman gives 14 feet (4.3 m) (Spillman 1997, pp. 75–76)

- Spillman gives a diameter of 11 inches (280 mm).(Spillman 1997, pp. 75–76)

- After sliding into the soil or rock beneath or around the target, the energy of detonation is transferred into the structure or creates a camouflet (cavern or crater) into which the target would fall.

- The Royal Air Force introduced into operational service in 1943 an improved precision bombsight: the Stabilizing Automatic Bomb Sight. 617 Squadron achieved a precision of 100 yd (91 m) at the V1 Weapon launch site at Abbeville on 16/17 December 1943. Bomber Command Diary December 1943 Archived 3 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- The Disney's explosive charge was 11% of the weight of the bomb. Around 50% of the weight of conventional bombs is explosive (see General-purpose bomb)

- The Disney bomb was officially codenamed the 4500-lb CP/RA bomb (Project Ruby 1946, p. 1). CP/RA stands for Concrete Piercing/Rocket Assisted.

- The No.58 MK I tail Pistol that also equipped the Tallboy bombs were manufactured by Midgley Harmer Limited (London).

- Switch activated by changes in atmospheric pressure. Also known as "baroswitch". See Applications of pressure sensors.

- Other sources mention a striking speed of 2,400 feet per second (730 m/s; 1,600 mph). (Johnsen 2003, p. 45, Burakowski & Sala 1960, p. 556)

- A film adaptation of the book Victory Through Air Power by the air warfare advocate Alexander de Seversky

- Strategic attacks against German shipping, warships and ports were carried out by RAF Coastal Command.

- The RRL had aided the development of Barnes Wallis' bouncing bomb.

- The reason for this is unclear. In the Avro Lancaster, the RAF had a bomber with a large enough bomb bay and sufficient lift. Several sources (Freeman 2001, p. 228; McArthur 1990, p. 280) cite unspecified technical reasons that prevented the use of British aircraft. Terrell states that the B-17 was the only aircraft capable of bearing the weight "under its wings" (Admiralty Brief p.201).

- "Bombs Versus Concrete". Flight. XLIX (1953): 537–541. 30 May 1946. ISSN 0015-3710. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

The U.S. component is dropping bombs ranging from 2000 lb to 22,000 lb (...) in addition to a new type of 4,500-lb rocket-assisted armour-piercing bomb, two of which are slung externally under the wing roots of a B-17. The rocket motor is cut in at a predetermined height after release and a direct hit is essential to effectiveness. An official film of "Project Ruby" shows that the missile resembles the German "P.C." series carried by Ju 87s and Ju 88s, though the rocket motor, detachable from the warhead, appears even longer. For " technical reasons " no British aircraft can handle this bomb

Flight makes references to the German Rocket-Propelled Bomb PC 1000 Rs. (U.S. Office of Chief of Ordnance (1 March 1945). "PC 1000 Rs: Rocket-Propelled Bomb". Catalog of Enemy Ordnance Materiel. p. 316. Retrieved 10 June 2011.The German 1,000 kg. (actual wt. 2,176 lb.) armor-piercing bomb (PC 1000 Rs) is a rocket-propelled type designed primarily for use against ships or similar targets.(...) There are three other bombs of the same general type: PC 500 Rs; a lighter version of the PC 1000 Rs; PC 1000 Rs Ex, for practice or experimental use (...) and the PC 1800 Rs.

- Only SBB2 has remained until today (52°27′36.72″N 4°34′39.08″E).

- Air Ministry (1954). Royal Air Force manual: organization (PDF) (2d ed.). p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

The Air Council is the ruling body at the head of the Air Ministry, and is responsible for the control and administration of the Royal Air Force. This responsibility is a joint one and is shared by all members of the Air Council. Any order emanating from the Air Council to R.A.F. formations is issued "by command of the Air Council".

References

- Citations

- Project Ruby 1946, p. 25

- USSTAF Armament Memorandum 1945, pp. 1–2

- Keefer 1947

- Combat bulletins CB n°57: Activities in ETO—Disney swish. Wikimedia Commons: US Army Pictorial Service. 1945.

- Ellis, John (1998). One Day in a Very Long War. Jonathan Cape. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-22404-244-4.

- Murray 2009

- Allen, Raymond (December 1943). "Bombsight Solves Problems". Popular Science. 143 (6). ISSN 0161-7370. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- Flower 2004

- Young 1997, Appendix B: Penetration Equations Summarized

- Terrell 1958

- Burakowski & Sala 1960, p. 557

- Spillman 1997, p. 76

- Project Ruby 1946, pp. 87–88

- Burakowski & Sala 1960, p. 556

- Project Ruby 1946, p. 18

- Project Ruby 1946, p. 23

- Spillman 1997, p. 75

- McArthur 1990, p. 280

- Terrell 1958, pp. 197–212

- "Rocket-Assisted Bomb Found at French Museum". Britain at War Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- "Terrell Family Name". Balean.net. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- US patent 1724980, Edward Terrell, "Vegetable or Like Peeling Knife", published 20 August 1929

- US patent 2215942, Edward Terrell, "Bottle", published 24 September 1940

- Terrell 1958, pp. 200–203

- Terrell 1958, pp. 205–207

- Freeman 2001, p. 228

- Freeman & Osbourne 1998, p. 50

- Thom 1986, p. 222

- Spillman 1997, p. 48

- Hecks 1990, p. 259

- Flower 2004, p. 203

- Flower 2004, p. 301

- Flower 2004, Appendix A

- Bateman 2009, p. 92

- Freeman 1990, p. 437

- Spillman 1997, p. 49

- Freeman 1990, p. 463

- Spillman 1997, p. 50

- Flower 2004, p. 350

- Marc Buggeln. "Neuengamme / Bremen-Farge". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Flower 2004, p. 348

- Flower 2004, p. 351

- Freeman 1990, p. 479

- Spillman 1997, p. 52

- Freeman 1990

- Project Ruby 1946, p. 214

- Terrell 1958, p. 224

- Project Ruby 1946, p. 6

- Project Ruby 1946, p. 7

- "Bombs Versus Concrete". Flight. XLIX (1953): 537. 30 May 1946.

- Howell, Mark (30 December 2009). "Project Ruby – a look at RAF Mildenhall's history". US Air Force. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- Project Ruby 1946, pp. 45–48

- Project Ruby 1946, p. 15

- Project Ruby 1946, p. 22

- Project Ruby 1946, p. 34

- Project Ruby 1946, p. 2

- Project Ruby 1946, p. 13

- Project Ruby 1946, p. 12

- Lavenant, Gwénaëlle (28 January 2009). "La bombe du blockhaus s'est envolée vers une nouvelle vie". La Voix du Nord (in French). Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

Après plus d'une semaine de travaux, la bombe qui était fichée dans le toit du blockhaus d'Éperlecques a été déposée à terre, hier, dans un camion de la sécurité civile, avant d'être transportée au centre de stockage de Vimy.

- Bibliography

- Air Proving Ground Command Eglin Field (31 October 1946). Comparative Test of the Effectiveness of Large Bombs against Reinforced Concrete Structures (Anglo-American Bomb Tests – Project Ruby) (PDF) (Report). Orlando, Florida: US Air Force. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

Running parallel with the development of large bombs was a project for obtaining high striking velocities by means of a rocket assisted 4,500-lb British bomb called the Disney. (...) As early as June 1945, the concrete V-weapon structure at Watten was used as a target.

- Bateman, Alex (2009). Tony Holmes (ed.). No 617 'Dambusters' Sqn. Oxford: Osprey. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-84603-429-9.

- Burakowski, Tadeusz; Sala, Aleksander (1960). Rakiety i Pociski Kierowane [Rockets and guided missiles] (in Polish). Część 1 – Zastosowania (Volume 1 – applications). Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej (Ministry of National Defense Publishing House). pp. 556–557. Figure 280, p. 558, provides a detailed diagram of the Disney bomb (with its internals).

- Flower, Stephen (2004). Barnes Wallis' Bombs: Tallboy, Dambuster & Grand Slam. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2987-8.

- Freeman, Roger A. (1990). The Mighty Eighth War Diary. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 978-1-85409-071-3.

- Freeman, Roger A.; Osbourne, David (1998). B-17 Flying Fortress Story: Design, Production, History. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 978-1-85409-301-1.

- Freeman, Roger A. (2001). The Mighty Eighth War Manual. London: Cassell & Co. ISBN 978-0-304-35846-5.

- Hecks, Karl (1990). Bombing 1939–45 : the Air Offensive Against Land Targets in World War Two. London: Hale. ISBN 978-0-7090-4020-0.

- Keefer, I. J. (December 1947). March Air Force Base (ed.). Project Harken – part II Bombing and Analysis and Related Subjects. American and British Phase (Report). Riverside, California: US Air Force. p. 6. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- Johnsen, Frederick A. (2003). Weapons of the Eighth Air Force. St. Paul, MN: MBI Publishing. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-7603-1340-4.

- McArthur, Charles (1990). Operations Analysis in the U.S. Army Eighth Air Force in World War I. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Soc. pp. 279–280. ISBN 978-0-8218-0158-1.

- Murray, Iain (2009). Bouncing-bomb Man : the Science of Sir Barnes Wallis. Sparkford: Haynes. ISBN 978-1-84425-588-7.

- Terrell, Edward (1958). Admiralty Brief: the Story of Inventions that Contributed to Victory in the Battle of the Atlantic. London: Harrap. OCLC 504731245.

- Thom, Walter (1986). The Brotherhood of Courage: The History of the 305th Bombardment Group (H) in World War II. New York: W. Thom. OCLC 18702434.

- Spillman, Pat (1997). "The Disney Bomb Project". 92nd Bomb Group (H): Fame's Favored Few. New York: Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-56311-241-6.

- United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe (28 January 1945). USSTAF Armament Memorandum (Report). 133–3. pp. 1–2.

- Young, C.W. (1997). Penetration Equations (PDF) (Report). SAND94-2726. Albuquerque NM: Sandia National Laboratories.

This is a standalone report documenting the latest version of the Young/Sandia penetration equations and related analytical techniques to predict penetration into natural earth materials and concrete.

Further reading

- Young, C.W. (1967). The Development of Empirical Equations for Predicting Depth of an Earth Penetrating Projectile (Report). SC-DR-67-60. Albuquerque NM: Sandia National Laboratories.

- Alekseevskii, V. P. (1966). "Penetration of a Rod into a Target at High Velocity". Combustion, Explosion, and Shock Waves (Fizika Goreniya i Vzryva). 2 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1007/BF00749237. ISSN 0010-5082. S2CID 97258659.

- Tate, A. (1 November 1967). "A Theory for the Deceleration of Long Rods After Impact" (PDF). Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids. 15 (6): 387–399. Bibcode:1967JMPSo..15..387T. doi:10.1016/0022-5096(67)90010-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- Bernard, Robert S. (1978). Depth and Motion Prediction for Earth Penetrators (Report). ADA056701. Vicksburg, MS: Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station Vicksburg.

- Walters, William P.; Segletes, Steven B. (1991). "An Exact Solution of the Long Rod Penetration Equations". International Journal of Impact Engineering. 11 (2): 225–231. doi:10.1016/0734-743X(91)90008-4.

- Segletes, Steven B.; Walters, William P. (2002). Efficient Solution of the Long-Rod Penetration Equations of Alekseevskii-Tate (PDF) (Report). ARL-TR-2855. Aberdeen, MD: Army Research Lab Aberdeen Proving Ground MD.

- Segletes, Steven B.; Walters, William P. (2003). "Extensions to the Exact Solution of the Long-Rod Penetration/Erosion Equations" (PDF). International Journal of Impact Engineering. 28 (4): 363–376. doi:10.1016/S0734-743X(02)00071-4. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

External links

- B17 having Disney Bombs Fitted 92nd Bomb Group, WW2 on YouTube. A short colour clip showing a parked B-17, loaded with Disney bombs

- The Disney bomb was used by the 92ndBomb Group in the closing months of WW2 on YouTube. A short colour clip showing a B-17 taking off with Disney bombs

- Project Ruby – a look at RAF Mildenhall's history