Dohna Castle

Dohna Castle (German: Burg Dohna, Czech: hrad Donín) on the once important medieval trade route from Saxony to Bohemia was the ancestral castle seat of the Burgraves of Dohna. Of the old, once imposing double castle only a few remnants of the walls remain. The ruins of the old castle are located on the hill of Schlossberg near the subsequent suburb of the town of the same name, Dohna, in the district of Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge in Saxony, Germany.

| Dohna Castle | |

|---|---|

Burg Dohna | |

| Dohna | |

Wall remains of the old Dohna castle | |

Dohna Castle | |

| Coordinates | 50°57′05″N 13°51′14″E |

| Type | hill castle, spur castle |

| Code | DE-SN |

| Height | 155 m above sea level (NN) |

| Site information | |

| Condition | wall remnant |

| Site history | |

| Built | around 950 |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | burgraves, nobility |

.jpg.webp)

History

Dohna Castle was probably founded around A.D. 950 by Emperor Otto I (936–973) on the Schlossberg hill on the site of a Sorbian hillfort fortification. This region around the Schlossberg had been a Sorbian settlement from prehistoric times. The name of the associated settlement was Donin, from which the castle received its name. The castle was the centre of the imperially immediate lordship of the burgraves of Dohna. They had the task of guarding the important trade route between Saxony and Bohemia, hold the conquered and subjugated Sorbs in serfdom and their Christianization by protecting emissaries of the Catholic Church.

Early history

Dohna Castle was first mentioned in records in 1040 in connection with the conflicts between King Henry III (1039–1056) and Duke Bretislaus of Bohemia. The Margravate of Meissen under Eckard II (1038–1046) held Dohna Castle presumably as an imperial fief of the Holy Roman Empire. Later, the castle fell under the lordship of burgraves from the Duchy of Bohemia.

In 1076, the Duke, and later King, of Bohemia, Vratislaus II (1061–1092), was enfeoffed by Henry IV (1056–1106) with the Gau of Nisani. He ceded the Gau of Nisani with Dohna Castle to his son-in-law, Wiprecht of Groitzsch, who later became the Margrave of Meissen (1123–1124), as a dowry for his daughter. In 1112 Wiprecht of Groitzsch relinquished Nisani and Dohna Castle to Henry V (1106–1125). On recovering possession of the castle by Groitzsch in 1117, Bohemian supremacy was re-established. At the beginning of the 12th century Dohna Castle was destroyed, but then rebuilt by the Duke of Bohemia, Vladislaus I (1109–1125) around 1121.

The following description of the dungeon is found in August Schumann's State Lexicon of Saxony (Staatslexikon von Sachsen):...and was, as with every strong castle at that time, according to custom of the day, sometimes used as a state prison. At the very least, it is known that the Bohemian king, Sobeslaus [Soběslav], marched several Bohemian lords to the dungeon at Dohna during the 1126....[2]

Of the burgraves installed as imperial officials on a certain Erkembert (from the family of Tegkwitz?) is named in 1113, referred to in the records Erkembertus prefektus de castro Donin.[3] It is also known that the family of the Erkenbertingers (recorded as burgraves in 1113) came from Franconia, established themselves in the vicinity of Naumburg and that their relatively junior Starkenberg line played a role in the Ore Mountains, for example in land development (Landausbau).[4]

Seat of the Donins

The progenitor of the Donins, who ruled from Dohna Castle for some 250 years, was Burgrave Henry I of Dohna, who is mentioned for the first time in 1143 as Heinricus de Rodewa (Rötha)[5] and 1144, albeit without giving the location, for the first time documented as burgrave (Latin praefectus).[6][7] The actual enfeoffment is not recorded, but must have taken place no later than 1156, when Henry is first expressly referred to as the Burgrave of Dohna.[8]

The powerful castle of Dohna perched on a rocky spur, 155 m above sea level (NN) near the River Müglitz, was the centre point of the Burgraviate of Dohna. It was here that the Dohnaer Schöppenstuhl was held, a magistrate's court (Schöffengericht) recorded since 1390 that operated until 1572, predominantly in the field of feudal and inheritance matters and gave legal direction over an area that extended far beyond the borders of Saxony.

One can assume that during the rule of the Dohna hereditary burgraves, the castle was expanded in such a way that it finally appeared as imposing double castle, consisting of an inner and outer castle (Hinterburg and Vorderburg) and a large ward (Vorhof). During the excavations of 1904/06, the exposure of the transverse wall separating the two castles, proved this theory.

The oval-shaped castle tower on the Fleischerbrunnen well in Dohna's market square, created in 1912 by the Dresden sculptor, Alexander Höfer, portrays the tower in the oldest town coat of arms of 1525.

Loss and ruin of the imperial castle

In the wake of the Dohna Feud (1385–1402), which began between Burgrave Jeschke von Dohna and the Meissen noble—Hans of Körbitz, the burgraves lost their main seat of power and all the estates belonging to it to the House of Wettin. The present Saxony-Bohemian state border was established in 1406, when the neighbouring Bohemian Pirna Castle with its associated villages and the Bohemian fortress of Königstein, in which Burgrave Jesche was able to seek refuge, were also won for the Wettins.[9]

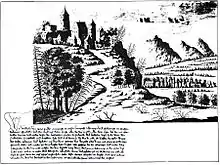

From autumn 1401 onwards the castle was besieged and, after lengthy resistance, was taken by storm on 19 June 1402 in the presence of Margrave William I the One-Eyed (1349/79–1407). After its capture the castle was not completely slighted. The residential buildings were left standing and served as residences for the margravial officials who managed the caretaking of Dohna. After the Vögte had moved their seat somewhere around 1457 to Pirna, the castle gradually fell into decay. In addition, the townsfolk of Dohna in subsequent times, may have helped themselves to large amounts of stone from the castle for building material whenever it was needed. In a picture from 1690 by A. Nienborg and in a sketch by Goebel in 1793 extensive remains of the walls and tower can still be seen.

M. Christian Bartsch, pastor in Dohna, wrote in 1735: ...on this castle hill you can still find the ruins of old walls, towers and vaults which have withstood the rain and weather for 330 years uncared for; but whose limestone and rock are so strong that you can only pull them down with difficulty, but which do not collapse by themselves. The Swedes when they stood here in 1709, tried to break into a vault in this castle hill, perhaps they thought they would find treasure, but had to give up soon thereafter due to the strength of the walls.....[10]

Today only a small remnant of the wall of the old castle may still be seen. Apart from that there is nothing else left of Dohna Castle.

Construction of castle hill after the decay of the castle ruins

_2006-10-19.jpg.webp)

In 1803 Burgrave Henry Louis of Dohna bought the castle hill (Schlossberg) in order to rebuild the castle in the spirit of the growing Romanesque movement. The castle hill was therefore cleared of rubble and the work began on the construction of a round tower. But the Napoleonic Wars prevented his romantic plans from being fulfilled. Eventually the round tower was completed in its present shape in 1830.

The "Privileged Shooting Association of Dohna" (Privilegierte Schützengesellschaft zu Dohna) bought the Schlossberg in 1826 for 700 thalers and levelled the front part of the hill. From the rock material of the castle walls they built the shooting house (Schießhaus) in 1828, the shooting wall and the supporting wall of the access track.

The buildings on the Schlossberg today consist mainly of the former shooting house, now a castle inn (Burgschänke) used as a Handelsorganisation restaurant and dancing hall, and the round tower built in the style of the old castle and last used as a museum area, in which local minerals from the Müglitz valley e. g. amethysts and agates could be admired.

In the castle inn ("Burg Dohna" restaurant) there has been a local history museum on the first floor since 1958, although it was founded in 1906. Today the local history museum is in the old chemist's in the market square. Here there are intera alia interesting exhibits of castle history e.g. discoveries from the Middle Ages, graphic works and documents.

Present use

The buildings of the Schlossberg, the round tower from 1830 and the former Burgschänke, have been converted into a meeting centre since 2005 by the Christian-free church Eckstein-community. Supporter is the registered association Horizon Worldwide Eckstein (Horizonte Weltweit Eckstein).

The castle site is a protected heritage site as is the Sorbian hillfort at the back of the spur that was called Robisch hillfort (Robsch, Robscher). This hillfort is still visible on a spur over the railway station yard. This site is mentioned because, even before the settlement of the castle hill (Schlossberg), a Sorbian gord (burgwall) had stood on the Robisch Hillfort.

Round tower and former castle inn buildings (Burgschänke)

Round tower and former castle inn buildings (Burgschänke) The round tower of 1830 on the Schlossberg with view of St. Mary's Church (Dohna) in the background

The round tower of 1830 on the Schlossberg with view of St. Mary's Church (Dohna) in the background 1902 Dohna medallion, obverse, with the castle tower

1902 Dohna medallion, obverse, with the castle tower Reverse side with 10 line inscription

Reverse side with 10 line inscription

See also

- List of castles in Saxony

- List of Burgraves of Dohna

- Dohna

- House of Dohna

- Dohna Feud

- Jeschke von Dohna

Literature

- Max Winkler und Hermann Raußendorf: Die Burggrafenstadt Dohna. In: Mitteilungen des Landesvereins Sächsischer Heimatschutz. Band 25, H. 1–4, Dresden 1936 (Datensatz der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek).

- Henning/Müller/Wintermann: Weesenstein. 700 Jahre Schlossgeschichte. Dresden 1995

- Christine Klecker: Wie Dohna verloren ging. Museum Schloß Weesenstein, 1991

- Hans Eberhard Scholze: Schloß Weesenstein. Leipzig 1969

- Herbert Wotte: Barockgarten Großsedlitz / Dohna - Wesenstein - Wilisch, Heft 99, VEB Bibliograqhisches Institut Leipzig, 1961

- Autorenkollektiv mit Dr. sc. Werner Coblenz: Historischer Führer Bezirke Dresden, Cottbus, Seite 118: Dohna (mit Burg Dohna). Urania-Verlag Leipzig-Jena-Berlin, Leipzig 1982

- Karlheinz Blaschke: Geschichte Sachsens im Mittelalter, Unionverlag Berlin, 1990

- Christian Bartsch. Historie der alten Burg und Städgens Dohna. Dresden/Leipzig 1735 (Digitalisat)

- Historische Kommission der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: NEUE DEUTSCHE BIOGRAPHIE, 4. Band, Berlin, 1957. Darin: 1127 Henricus nobilis de Rotowe (Rötha), hat seit 1156 die Burggrafschaft Donin als Reichslehen inne. (Digitalisat)

- Schumann, August (1814). "Dohna". Vollständiges Staats-, Post- und Zeitungslexikon von Sachsen (in German). 1. Zwickau. p. 756. Darin: Burg Dohna

References

- Heckel C. (1736), Historischen Beschreibung der weltberühmten Vestung Königstein, Dresden, 1736.

- Vgl. Schumann, August (1814). "Dohna". Vollständiges Staats-, Post- und Zeitungslexikon von Sachsen (in German). 1. Zwickau. p. 755.

- Vgl. Digital Historic Index of Places in Saxony - Dohna (1113)

- Team of authors with Dr. sc. Werner Coblenz: Historischer Führer Bezirke Dresden, Cottbus, page 118: Dohna (and Dohna Castle). Urania-Verlag Leipzig-Jena-Berlin, Leipzig, 1982

- Heinricus de Rodewa in a deed by King Conrad III for Chemnitz Abbey dated February 1143; Henry is named as a witness. See the edition of the document at: The charters of Conrad III and his son Henry, arranged by Friedrich Hausmann (= MGH DD, Vol. 9), Vienna/Cologne/Graz 1969, No. 86, p. 152-154, here p. 154 line 17. For the first record in 1143 see: Karlheinz Blaschke, Dohna, in: Lexikon des Mittelalters, Vol.3, Munich et al. 1983, Sp. 1166.

- Heinricus praefectus (without naming the place!) in a deed of King Conrad III dated November 1144, that mediates a dispute between the Bishop and Margrave of Meißen; Henry is named as a witness. The name index of the MGH-Editionsbandes identifies him as the Henry already named in 1143. See: The Charters of Conrad III and his son, Henry, arranged by Friedrich Hausmann (= MGH DD, Bd. 9), Vienna/Cologne/Graz 1969, No. 119, p. 212-214, here p. 214 line 4.

- Art. Dohna, in: Digital Historical Index of Places in Saxony, Naming patterns (Ortnamenformen), entry for 1144.

- Heinricus castellanus de Donin in a charter of Margrave Conrad I of Meißen dated 30 November 1156; Henry is named as a witness. See: Codex diplomaticus Saxoniae regiae, I A 2: Die Urkunden der Markgrafen von Meißen und Landgrafen von Thüringen 1100-1195, ed. by Otto Posse, Leipzig, 1889, No. 262 p. 176-179, here p. 178 line 37 Archived 2007-06-30 at the Wayback Machine. See also Lothar Graf zu Dohna (1959), "Dohna", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 4, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 43–46, p. 43.

- Karlheinz Blaschke: Geschichte Sachsens im Mittelalter, Unionverlag Berlin, 1990

- Vgl. Christian Bartsch. Historie der alten Burg und Städgens Dohna. Dresden/Leipzig 1735 digitalised version

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Burg Dohna. |

- The castle on the Dohna Local History Society website

- Website of the town of Dohna, with Dohna Castle under history (Geschichte)

- Digital Historical Index of Places in Saxony - Dohna. incl: 1144 Heinricus praefektus, 1156 Heinricus castellanus de Donin

- Digital Historical Index of Places in Saxony - Rötha. incl: 1127 Heinricus de Rotow, 1135 Rotwe, 1143 Rodewa, - 1127: Herrensitz (um Mitte des 12. Jahrhunderts Ortswechsel als Burggrafen nach Dohna)

- East Prussia, information about the County of Dohna. incl: Henricus nobilis de Rotowe 1127/1156

- Dohna at www.schlossarchiv.de