Domestic duck

Domestic ducks are ducks that are raised for meat, eggs and down. Many ducks are also kept for show, as pets, or for their ornamental value. Almost all varieties of domestic duck apart from the Muscovy duck (Cairina moschata) are descended from the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos).[1][2]

| Domestic duck | |

|---|---|

| |

| A group of Indian Runner ducks | |

Domesticated | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Anas |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | A. p. domesticus |

| Trinomial name | |

| Anas platyrhynchos domesticus | |

Domestication

Mallard ducks were first domesticated in Southeast Asia at least 4000 years ago, during the Neolithic Age, and were also farmed by the Romans in Europe, and the Malays in Asia.[3][4] In ancient Egypt, ducks were captured in nets and then bred in captivity.[5] During the Ming Dynasty, the Peking duck—mallards force-fed on grains, making them larger— was known to have good genetic characteristics.[6]

Almost all varieties of domestic duck except the muscovy have been derived from the mallard.[7] Domestication has greatly altered their characteristics. Domestic ducks are mostly polygamous, where wild mallards are monogamous. Domestic ducks have lost the mallard's territorial behaviour, and are less aggressive than mallards.[8][9] Despite these differences, domestic ducks frequently mate with wild mallard, producing fully fertile hybrid offspring.[10]

Farming

Ducks have been farmed for thousands of years.[11] Approximately 3 billion ducks are slaughtered each year for meat worldwide.[12] In the Western world, they are not as popular as the chicken, because chickens have much more white lean meat and are easier to keep confined, making the total price much lower for chicken meat, whereas duck is comparatively expensive. While popular in haute cuisine, duck appears less frequently in the mass-market food industry and restaurants in the lower price range. However, ducks are more popular in China and there they are raised extensively.

Ducks are farmed for their meat, eggs, and down. A minority of ducks are also kept for foie gras production. The blood of ducks slaughtered for meat is also collected in some regions and is used as an ingredient in many cultures' dishes. Their eggs are blue-green to white, depending on the breed.

Ducks can be kept free range, in cages, in barns, or in batteries. Ducks enjoy access to swimming water, but do not require it to survive. They should be fed a grain and insect diet. It is a popular misconception that ducks should be fed bread; bread has limited nutritional value and can be deadly when fed to developing ducklings. Ducks should be monitored for avian influenza, as they are especially prone to infection with the dangerous H5N1 strain.[13]

The females of many breeds of domestic ducks are unreliable at sitting their eggs and raising their young. Exceptions include the Rouen duck and especially the Muscovy duck. It has been a custom on farms for centuries to put duck eggs under broody hens for hatching; nowadays this role is often played by an incubator. However, young ducklings rely on their mothers for a supply of preen oil to make them waterproof; a chicken hen does not make as much preen oil as a female duck, and an incubator makes none. Once the duckling grows its own feathers, it produces preen oil from the sebaceous gland near the base of its tail.[14]

Pets and ornamentals

Domestic ducks can be kept as pets, in a garden or backyard, generally with a pond or deep water dish. If they are given access to a pond, they dabble in the mud, dredging out and eating wildlife and frog spawn, and swallow adult frogs and toads up to the size of the common frog Rana temporaria, as they have been bred to be much bigger than wild ducks, with a waterline length (base of neck to base of tail) of up to 1 foot (30 cm); the wild mallard's waterline length is about 6 inches (15 cm). Protection from predators such as foxes and hawks is required.[15]

Ducks are also kept for their ornamental value. Breeds have been developed with crests and tufts or striking plumage, for exhibition in competitions.[16]

In culture

In children's stories

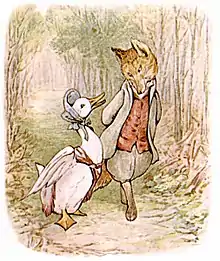

The domestic duck has appeared numerous times in children's stories. Beatrix Potter's The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck was published by Frederick Warne & Co in 1908. One of Potter's best-known books, the tale was included in the Royal Ballet's The Tales of Beatrix Potter.[17] It is the story of how Jemima, a domestic duck, is saved from a cunning fox who plans to kill her, when she tries to find a safe place for her eggs to hatch.[18]

Make Way for Ducklings is a children's picture book written and illustrated by Robert McCloskey. First published in 1941, the book tells the story of a pair of mallards who decide to raise their family on an island in the lagoon in Boston Public Garden, a park in the center of Boston. Make Way for Ducklings won the 1942 Caldecott Medal for McCloskey's illustrations.

The Disney cartoon character Donald Duck, one of the world's most recognizable pop culture icons, is a domestic duck of the American Pekin breed.

In music

The domestic duck features in the musical composition Peter and the Wolf, written by Sergei Prokofiev in 1936. The orchestra illustrates the children's story while the narrator tells it.[19] In this, a domestic duck and a little bird argue on each other's flight capabilities. The duck is represented by the oboe. The story ends with the wolf eating the duck alive, its quack heard from inside the wolf's belly.[20]

In art

Domestic ducks are frequently depicted in wall paintings and grave objects from ancient Egypt.[21] They are featured in a range of ancient artefacts, which revealed that they were a fertility symbol.[22]

As food

Since ancient times, the duck has been eaten as food.[23] Usually only the breast and thigh meat is eaten.[24] It does not need to be hung before preparation, and is often braised or roasted, sometimes flavoured with bitter orange or with port.[25] Peking duck is a dish of roast duck from Beijing, China, that has been prepared since medieval times. It is today traditionally served with spring pancakes, spring onions and sweet bean sauce.[26][27]

References

- "Anas platyrhynchos, Domestic Duck; DigiMorph Staff - The University of Texas at Austin". Digimorph.org. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- Sy Montgomery. "Mallard; Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- Titlow, Budd (2013). Bird Brains: Inside the Strange Minds of Our Fine Feathered Friends. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-762-79770-7.

- Kear, Janet (2005). Ducks, Geese and Swans: General chapters, species accounts (Anhima to Salvadorina). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-61008-3.

- Manuelian, Peter der (1998). Egypt: The World of the Pharaohs. Cologne, Germany: Könemann. p. 381. ISBN 978-3-89508-913-8.

- Cherry, Peter; Morris, Trevor Raymond (2008). Domestic Duck Production: Science and Practice. CABI. ISBN 9781845934415.

- Appleby, Michael C.; Mench, Joy A.; Hughes, Barry O. (2004). Poultry Behaviour and Welfare. CABI. ISBN 978-0-851-99667-7.

- Piggott, Stuart; Thirsk, Joan (February 1981). The Agrarian History of England and Wales: Volume 1, Part 1, Prehistory. Cambridge University Press Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-08741-4.

- DigiMorph Staff –The University of Texas at Austin (2004). "Anas platyrhynchos, Domestic Duck". Digimorph.org. Archived from the original on 27 November 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- Wood-Gush, D. (2012). Elements of Ethology: A textbook for agricultural and veterinary students. Springer. ISBN 978-9-400-95931-6.

- Kiple, Kenneth F.; Ornelas, Kriemhild Coneè (2000). The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40214-9. OCLC 44541840.

- "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Songserm, Thaweesak; Jam-on, Rungroj; Sae-Heng, Numdee; Meemak, Noppadol; Hulse-Post, Diane J.; Sturm-Ramirez, Katharine M.; Webster, Robert G. (April 2006). "Domestic Ducks and H5N1 Influenza Epidemic, Thailand". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (4): 575–581. doi:10.3201/eid1204.051614. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 3294714. PMID 16704804.

- "Ducks - Poultry Breeds Encyclopedia".

- Link, Kimberly (2014). The Ultimate Pet Duck Guidebook. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1500344771.

- "The best ducks to keep in your garden: in pictures". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- Roberts, Laura (16 December 2010). "The Tales of Beatrix Potter performed by The Royal Ballet". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- Potter, Beatrix (1993). Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck. Frederick Warne. ISBN 9781854713858.

- Rijke, Victoria de (2008). Duck. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-861-89489-2.

- Prokofiev, Sergei (1999). Peter and the Wolf. North-South Books. ISBN 978-0-735-81189-8.

- LeMaster, Richard (March 1995). The Great Gallery of Ducks and Other Waterfowl. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-811-70706-0.

- Chadd, Rachel Warren; Taylor, Marianne (2016). Birds: Myth, Lore and Legend. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-472-92287-8.

- Dalby, Andrew (2013). Food in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-95422-2.

- The Visual Food Encyclopedia. Québec Amerique. 1996. ISBN 978-2-764-40898-8.

- Davidson, Alan (2006). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press. p. 472. ISBN 978-0-191-01825-1.

- "The Evolution of Peking Duck". CBS. 24 September 2006.

- "A Cultural Classic: Peking Duck". Globe Trekker. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Domesticated ducks. |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

- Duck and Goose from Farm to Table factsheet from USDA