Donald Cargill

Donald Cargill (1619 – 27 July 1681) was a Scottish Covenanter who worked to uphold the principles of the National Covenant of 1638 and Solemn League and Covenant of 1643 to establish and defend Presbyterianism. He was born around 1619, and was the eldest son of Laurence Cargill of Bonnytoun, Rattray, Perthshire, a notary public, and Marjory Blair.[1] He was educated perhaps at University of Aberdeen and at the University of St Andrews, where he matriculated as a student of St Salvator's College in 1645. He was licensed by the Presbytery of St Andrews on 13 April 1653 and was ordained in 1655. He was later deprived by the Privy Council, on 1 October 1662, for disobeying the Act of Parliament in not keeping a day of thanksgiving for His Majesty's Restoration, and not obtaining presentation and collation from the archbishop before 20 September. He was ordered at the same time to remove beyond the Tay before 1 November under penalties. Disregarding this sentence, he was charged to appear before the Council on 7 January 1669, and appointed to continue in his confinement, but on petition he was allowed to visit Edinburgh about law affairs. He refused an indulgence at Eaglesham on 3 September 1672. On 16 July 1674 a decreet was passed against him for holding conventicles. In 1679 he joined Richard Cameron in founding the Cameronians (afterwards the Reformed Presbyterians), who embodied their principles in a Declaration at Sanquhar, on 22 June 1680, disowning the king's authority. A reward of 3000 merks was offered for his apprehension, dead or alive. For excommunicating at Torwood in September 1680 Charles II., James, Duke of York, and others, the Privy Council increased the reward to 5000 merks. After numerous hair-breadth escapes he was apprehended at Covington Mill, Lanarkshire, during the night of 12 July 1681 by a party of dragoons led by James Irving of Bonshaw (who got the reward). Tried for treason before the High Court of Justiciary, he was found guilty, and executed at the Cross of Edinburgh with four others [Walter Smith, William Cuthil, William Thomson, James Boig], 27 July 1681. His forfeiture was rescinded by Act of Parliament 4 July 1690. He married Margaret (died 12 Aug. 1656, within a year and a day of their marriage), daughter of Nicol Brown, burgess of Edinburgh, widow of Andrew Bethune of Blebo.[2]

Donald Cargill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1619 |

| Died | 27 July 1681 |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Occupation | pastor |

| Known for | Covenanter |

Life

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Early life

He was born at Rattray, Blairgowrie and educated at Aberdeen and St Andrews Universities. In 1655 he was appointed Minister to the Parish of Barony in Glasgow. From the first he was a man of deep convictions and intense fidelity to them, but he did not become prominent till the time of the king's restoration.[3]

Day of thanksgiving?

On 29 May 1662, on a day of thanksgiving for the Restoration of Charles II, he startled his congregation by beginning his sermon as follows:[4]

We are not come here to keep this day upon the account for which others keep it. We thought once to have blessed the day wherein the king came home again, but now we think we shall have reason to curse it; and if any of you come here in order to the solemnising of this day, we desire you to remove.

As a result of his protest, he was dismissed. Cargill was deprived of his benefice and banished beyond the Tay by the privy council (1 October 1662). He disregarded the sentence, became a field preacher, and was conspicuous for the earnestness with which he denounced the presbyterian ministers who accepted the 'indulgence' in 1672. On 16 July 1674 and 6 August 1675 decreets were passed against him for holding conventicles and other offenses.[5]

Bothwell Bridge and flight to Holland

Cargill was wounded at the Battle of Bothwell Bridge on 22 June 1679 between Royalists and Covenanters, and fled to the Netherlands.[6]

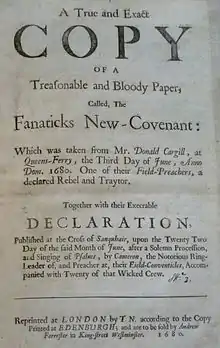

The Queensferry Paper

Returning to Scotland in 1680, Cargill drafted a declaration of principles, contained in the document known as The Queensferry Paper which fell into government hands on 4 June when he narrowly escaped arrest at an inn in the town of Queensferry. It called for signatories to "overthrow the kingdom of darkness" and pledge that "We shall to our power relieve the church and subjects of this kingdom of that opposition that hath been exercised upon their consciences, civil rights and liberties, that men may serve him holily, without fear, and possess their civil rights in quietness, without disturbance." It accused the rulers of having "degenerated from the virtue and good government of their predecessors into tyranny; governed contrary to all right laws, exercised such tyranny and arbitrary government, oppressed men in their consciences and civil rights ...",[7] and affirmed in its final article that, "We bind and oblige ourselves to defend ourselves, and one another, in our worshipping of God, and in our natural, civil and divine rights and liberties, till we shall overcome, or send them down under debate to posterity, that they may begin where we end."[8]

Sanquhar Declaration

On 22 June 1680 Cargill's associate Richard Cameron issued the Sanquhar Declaration, calling for war against King Charles II and the exclusion of his brother, afterwards James VII, from the succession. After Cameron's death in July at the hand of dragoons, Cargill continued to preach in the Torwood near Stirling and in September pronounced the sentence of excommunication against the key government figures who were persecuting the Covenanters: Charles II, James, Duke of York and James, Duke of Monmouth, Privy Councillors, John, Duke of Lauderdale and John, Duke of Rothes, the King's Advocate, Sir George McKenzie, and General Tam Dalziel of the Binns. The following extract gives a flavour of the pronouncement,

- "I, being a minister of Jesus Christ, and having authority and power from Him, do, in His name and by His spirit (...) excommunicate and cast out of the true Church, and deliver up to Satan, James, Duke of Monmouth, for coming into Scotland at his father's unjust command and leading armies against the Lord's people, who were constrained to rise, being killed in and for the worshipping of the true God, and for refusing, that morning, a cessation of arms at Bothwell Bridge, for hearing and redressing their injuries, wrongs and oppressions."[9]

At Torwood

In September, at Torwood, between Stirling and Falkirk, he pronounced, without concert with any one, a solemn sentence of excommunication against the king, the Duke of York, Duke of Monmouth, Duke of Lauderdale, Duke of Rothes, Sir George Mackenzie, and Sir Thomas Dalzell. The Torwood excommunication was published in 1741. A larger reward was therefore issued for his capture, and after many hair-breadth escapes he was taken on 12 September by James Irvine of Bonshaw at Covington Mill.[5]

Arrest and execution

Eventually Cargill was arrested, sentenced to death and hanged in Edinburgh on 27 July 1681. He is reported to have said to the crowd, "The Lord knows I go on this ladder with less fear and perturbation of mind, than ever I entered the pulpit to preach.".[10]

There is a monument to him at his birthplace in Rattray, Perthshire; and his name also appears on the Covenanters' Memorial near Maybole, South Ayrshire.

Personal life

He married Margaret Browne, relict of Andrew Betham of Blebo, in 1655, but his wife died 12 August 1656.[5]

Though Cargill's very stringent views were not generally accepted by his countrymen, both he and his friend Cameron took a great hold on the popular sympathy and regard. Personally, Cargill was an amiable, kind-heart man, very self-denying, and thoroughly devoted to his duty. Wodrow ascribes some of his extreme sentiments to the influence of others. Among the people he seems to have won admiration for the profoundness of his convictions and the fearlessness with which he acted on them, when the result to himself could not fail to be ruinous. Some sermons, lectures, and his last speech and testimony have been printed; but Peter Walker in the 'Remarkable Passages' in which he records his life in 'Biographia Presbyteriana,' indicates that the impression produced by them was far inferior to that of his spoken discourses.[5]

Bibliography

- — Letter to his Parishioners (Edinburgh, 1734);

- Torwood Excommunication, 1680 (1741);

- Lectures and Sermons (Howie Collect.) ;

- Last Speech and Testimony, with Four Letters (Cloud of Witnesses)

- Wodrow's Hist., iii., 279, passim ;

- Wodrow's Anal., i., 69 ;

- Shields' A Hind let Loose, 141 ;

- Walker's Six Saints of the Covenant [D. Hay Fleming, ed.], ii., 1-62, 199-203;

- The Cloud of Witnesses, 265-8;

- Hewison's Covenanters, ii., 157, passim ;

- Carslaw's Donald Cargill ;

- The Scots Worthies [Wylie], 526, passim.

- Grant, Maurice (1988). No King but Christ: The Story of Donald Cargill. Darlington: Evangelical Press. ISBN 0-85234-255-1. This biography posits a later date for Cargill's birth, as late perhaps as 1627.

- J. Howie, The Scots Worthies, Edinburgh and London, 1870

- J Barr, The Scottish Covenanters, Glasgow 1946

- M. Grant, The Lion of the Covenant, Evangelical Press, Darlington 1997, ISBN 0-85234-395-7 A modern biography of Richard Cameron.

- R. C. Paterson, A Land Afflicted, Scotland And The Covenanter Wars, 1638–1690, John Donald, Edinburgh 1998, ISBN 978-0-85976-486-5

- Blaikie, William Garden (1887). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 9. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

References

- Scott 1920, p. 391.

- Scott 1920, p. 392.

- Blaikie 1887, p. 79.

- Barr 1946, p. 77.

- Blaikie 1887, p. 80.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 329.

- Grant 1997, p. 229–30.

- Barr 1946, p. 52.

- Barr 1946, p. 76.

- Howie & Carslaw 1870, p. 452.

Sources

- Anderson, William (1877). "Cargill, Donald". The Scottish nation: or, The surnames, families, literature, honours, and biographical history of the people of Scotland. 1. A. Fullarton & co. p. 588.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Barr, James (1946). The Scottish Covenanters. Glasgow: Distributed on behalf of the author by J. Smith. Retrieved 12 July 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blaikie, William Garden (1887). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 9. London: Smith, Elder & Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Chambers, Robert; Thomson, Thomas (1857). A biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen. New ed., rev. under the care of the publishers. With a supplementary volume, continuing the biographies to the present time. 1. Glasgow: Blackie. pp. 513–515. Retrieved 20 April 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 329.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Douglas, J. D. (1964). "The Second Revolt". Light in the north : the story of the Scottish Covenanters (PDF). W. B. Eerdmans Pub. Co. pp. 140–152. Retrieved 22 April 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grant, Maurice (1997). The Lion of the Covenant. Darlington: Evangelical Press. ISBN 0-85234-395-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grub, George (1861). An ecclesiastical history of Scotland : from the introduction of Christianity to the present time. 3. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. pp. 261–262. Retrieved 8 July 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howie, John; Carslaw, W. H. (1870). "Donald Cargill". The Scots worthies. Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson, & Ferrier. pp. 439–453.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Irving, Joseph (1881). The book of Scotsmen eminent for achievements in arms and arts, church and state, law, legislation, and literature, commerce, science, travel, and philanthropy. Paisley: A. Gardner. p. 63. Retrieved 11 July 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Scott, Hew (1920). Fasti ecclesiae scoticanae; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation. 3. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. pp. 392–393. Retrieved 8 July 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Smellie, Alexander (1903). Men of the Covenant : the story of the Scottish church in the years of the Persecution (2 ed.). New York: Fleming H. Revell Co. pp. 277–285. Retrieved 11 July 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walker, James (1888). The theology and theologians of Scotland : chiefly of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. p. 189. Retrieved 22 April 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Walker, Patrick; Fleming, David Hay (1901). Six saints of the Covenant; Peden: Semple: Welwood: Cameron: Cargill: Smith. 2. London: Hodder and Stoughton. pp. 1–62. Retrieved 12 July 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walker, Patrick; Shields, Alexander; Stevenson, John (1827). Biographia Presbyteriana. 2. Edinburgh: D. Speare. pp. 1–54. Retrieved 18 April 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wodrow, Robert; Burns, Robert (1828). The history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland from the restoration to the revolution, with an original memoir of the author, extracts from his correspondence, and preliminary dissertation. 3. Glasgow: Blackie, Fullarton & co., and Edinburgh: A. Fullarton & co. p. 278. Retrieved 7 April 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wodrow, Robert; Leishman, Matthew (1842). Analecta: or, Materials for a history of remarkable providences; mostly relating to Scotch ministers and Christians. 1. Glasgow: Maitland Club. p. 69. Retrieved 8 July 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)