Earl Van Dorn

Earl Van Dorn (September 17, 1820 – May 7, 1863) was a United States Army officer and great-nephew of Andrew Jackson, fighting with distinction during the Mexican–American War, against several tribes of Native Americans, and in the Western theater of the American Civil War as a Confederate major general.

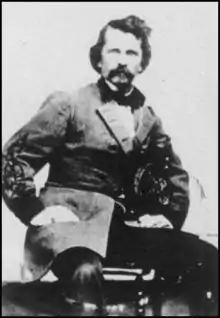

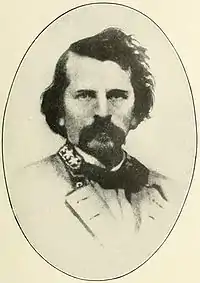

Major-General Earl Van Dorn | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Major-General Earl Van Dorn | |

| Nickname(s) | Buck, Damn Born |

| Born | September 17, 1820 Claiborne County, Mississippi |

| Died | May 7, 1863 (aged 42) Spring Hill, Tennessee |

| Place of burial | Wintergreen Cemetery Port Gibson |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War

Indian Wars Seminole Wars Comanche Wars American Civil War |

In the American Civil War, he served as a Confederate general, appointed commander of the Trans-Mississippi District. At the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in early March 1862, he was defeated by a smaller Union force, partly because he had abandoned his supply-wagons for the sake of speed, leaving his men under-equipped in cold weather. At the Second Battle of Corinth in October 1862, he was again defeated through a failure of reconnaissance and removed from high command. He then scored two notable successes as a cavalry commander, capturing a large Union supply depot in the Holly Springs Raid and an enemy brigade at the Battle of Thompson's Station, Tennessee. Van Dorn's successful raid of Holly Springs delayed the potential expulsion of Jewish people from Grant's military district.

Van Dorn's reputation was regained but short-lived.[1] In May 1863, he was shot dead at his headquarters at Spring Hill by a doctor who claimed that Van Dorn had carried on an affair with his wife. Two years later, in 1865, the Confederacy that Van Dorn had fought for ceased to exist, destroyed by a costly Civil War, after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomatox. Although a promising, fast moving, charismatic leader, Van Dorn never achieved military greatness, as did other top Confederate generals. The 21st century brought renewed historical interest in Van Dorn's Holly Springs raid, obstructing Grant's controversial General Order No. 11.

Early life and career

Van Dorn was born near Port Gibson in Claiborne County, Mississippi, to Sophia Donelson Caffery, a niece of Andrew Jackson, and Peter Aaron Van Dorn, a lawyer who had moved from New Jersey years earlier. He had eight siblings, including sisters, Emily Van Dorn Miller and Octavia Van Dorn (Ross) Sulivane. His sister Octavia, had a son, Clement Sulivane, who was a captain in the CSA forces and served on Earl's staff; he later became a lieutenant colonel. In December 1843, Van Dorn married Caroline Godbold, and they had a son named Earl Van Dorn, Jr. (b. 1855) and a daughter Olivia (1852-1878).[2][3]

In 1838, Van Dorn enrolled in the United States Military Academy at West Point graduated 52nd out of 68 cadets in the class of 1842.[4] His family relations to Andrew Jackson had secured him an appointment there.[5] He was appointed a brevet second lieutenant in the 7th U.S. Infantry Regiment on July 1, 1842, and began his army service in the Southern United States.[6]

Van Dorn and the 7th were on garrison duty at Fort Pike, Louisiana, in 1842–43, and were stationed at Fort Morgan, Alabama, briefly in 1843. He did garrison duty at the Mount Vernon Arsenal in Alabama from 1843 into 1844, and he was ordered to Pensacola harbor in Florida from 1844 to 1845, during which Van Dorn was promoted to second lieutenant on November 30, 1844.[6]

War with Mexico

Van Dorn was part of the 7th U.S. Infantry when Texas was occupied by the U.S. Army from 1845 into 1846, and spent the early stages of the Mexican–American War on garrison duty defending Fort Texas (Fort Brown) in Brownsville, the southernmost town in Texas.[7]

Van Dorn saw action at the Battle of Monterrey on September 21–23, 1846, and during the Siege of Vera Cruz from March 9–29, 1847.[6] He was then transferred to Gen. Winfield Scott's command in early 1847 and promoted to first lieutenant on March 3.[4] Van Dorn fought well in the rest of his engagements in Mexico, earning himself two brevet promotions for conduct; He was appointed a brevet captain on April 18 for his participation at the Battle of Cerro Gordo, and to major on August 20 for his actions near Mexico City, including the Battle of Contreras, the Battle of Churubusco, and at the Belén Gate. Van Dorn was wounded in the foot near Mexico City on September 3,[4] and wounded again during the storming of the Belén Gate on September 13.[7]

After the war with Mexico, Van Dorn served as aide-de-camp to Brev. Maj. Gen P. F. Smith from April 3, 1847, to May 20, 1848. He and the 7th were in garrison at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, from 1848 into 1849, and then at Jefferson Barracks in Lemay, Missouri, in 1849. He saw action in Florida against the Seminoles from 1849 to 1850, and was on recruiting service in 1850 and 1851.[6]

From 1852 to 1855 Van Dorn was stationed at the East Pascagoula Branch Military Asylum in Mississippi, serving as secretary then treasurer of the post.[7] He spent the remainder of 1855 stationed at New Orleans, Louisiana, briefly on recruiting service again, and then in garrison back at Jefferson Barracks.[6] He was promoted to captain in the 2nd Cavalry on March 3, 1855.[4] Van Dorn and the 2nd were on frontier duty at Fort Belknap and Camp Cooper, Texas, in 1855 and 1856, scouting in northern Texas in 1856, and fought a minor skirmish with Comanche on July 1, 1856. He was then assigned to Camp Colorado, Texas, in 1856 to 1857, scouting duty again in 1857, returned to Camp Colorado in 1857 to 1858, and finally stationed at Fort Chadbourne located in Coke County, Texas, in 1858.[6]

Van Dorn saw further action against the Seminoles and also the Comanches in the Indian Territory. He was wounded four separate times there,[6] including seriously when he commanded an expedition against Comanches and took two arrows (one in his left arm and another in his right side, damaging his stomach and lung) at the Battle of Wichita Village on October 1, 1858.[4] Not expected to live, Van Dorn recovered in five weeks. Van Dorn led six companies of cavalry and a company of scouts recruited from the Brazos Reservation in a spring campaign against the Comanche in 1859. He located the camp of Buffalo Hump in Kansas in a valley he erroneously identified as the Nescutunga (or Nessentunga), and defeated them on May 13, 1859, killing 49, wounding five and capturing 32 women. He served at Fort Mason, Texas, in 1859 and 1860.[6] While at Fort Mason, Van Dorn was promoted to the rank of major on June 28, 1860.[4] He then was on a leave of absence from the U.S. Army for the rest of 1860 and into 1861.[6]

Civil War service

Van Dorn chose to follow his home state and the Confederate cause, and he resigned his U.S. Army commission, which was accepted effective January 31, 1861.[4] He was appointed a brigadier general in the Mississippi Militia on January 23,[4] and replaced Jefferson Davis as major general and commander of Mississippi's state forces in February when Davis was selected as the Confederacy's President.[7]

After resigning from the Mississippi Militia on March 16, 1861, Van Dorn entered the Regular Confederate States Army as a colonel of infantry on that same date.[4] He was sent west to raise and lead a volunteer brigade within the new Confederate Department of Texas.[5] On April 11 he was given command of Confederate forces in Texas, and was also ordered to arrest and detain any U.S. troops in the state who refused to join the Confederacy.[8]

Leaving New Orleans on April 14 and arriving at Galveston, Texas, he and his men succeeded in capturing three Union ships in the town's harbor,[9] on April 17 and then headed for the last remaining regular U.S. Army soldiers in Texas at Indianola, forcing their surrender on April 23.[10][11] While at Indianola, Van Dorn attempted to recruit the captured U.S. soldiers into the forces of the Confederacy, but was largely unsuccessful.[12]

Van Dorn was summoned to Richmond, Virginia, and appointed a colonel in the 1st C.S. Regular Cavalry on April 25, leading all of Virginia's cavalry forces,[5] and then quickly promoted to brigadier general on June 5.[4] After being promoted to major general on September 19, 1861,[13] Van Dorn was given divisional command in the Confederate Army of the Potomac five days later, leading the 1st Division until January 10, 1862.[4] Around this time Confederate President Davis needed a commander for the new Trans-Mississippi District, as two of the leading Confederate generals there, bitter rivals Sterling Price and Benjamin McCulloch, required a leader to subdue their strong personalities and organize an effective fighting force. Both Henry Heth and Braxton Bragg had turned down the post, and Davis selected Van Dorn.[14] He headed west beginning on January 19 to concentrate his separated commands, and set up his headquarters at Pocahontas, Arkansas.[5] He assumed command of the district on January 29, 1862.[15]

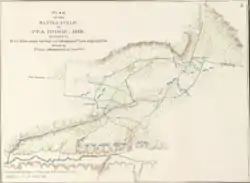

Pea Ridge

By early 1862, Federal forces in Missouri had pushed nearly all Confederate forces out of the state.[16] When Van Dorn took command of the department, he had to react with his roughly 17,000-man, 60 gun Army of the West to events already underway. Van Dorn wanted to attack and destroy the Union forces, make his way into Missouri, and capture St. Louis, turning over control of this important state to the Confederacy. He met his now-concentrated force near Boston Mountains on March 3, and the army began moving north the next day.[17]

In the spring of 1862, Union Brig. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis entered Arkansas and pursued the Confederates with his 10,500 strong Army of the Southwest. Curtis collected his four divisions and 50 artillery guns and moved into Benton County, Arkansas, following a stream called Sugar Creek. Along it on the northern side he found an excellent defensive position and began to fortify it, expecting an assault from the south.[16] Van Dorn chose not to attack Curtis's entrenched position head on. Instead he split his force into two, one division led by Price and the other by McCulloch, and ordered them to march north, hoping to reunite in Curtis' rear.[18] Van Dorn decided to leave behind his supply wagons in order to increase their moving speed, a decision that would prove critical.[19] Several other factors caused the proposed junction to be delayed, such as the lack of proper gear for the Confederates (some said to lack even shoes) for a forced march, felled trees placed across their path, their exhausted and hungry condition, and the late arrival of McCulloch's men. These delays allowed the Union commander to reposition part of his army throughout March 6 and meet the unexpected attack from his rear, placing Curtis' forces between the two wings of the Confederate army.[18] Plus when Van Dorn's advance guard accidentally ran into Union patrols near Elm Springs, the Federals were alerted to his approach.

The Battle of Pea Ridge would be one of the few instances in the American Civil War where the Confederate forces outnumbered the Union forces. Just prior to taking command of the district, Van Dorn wrote to his wife Caroline, saying "I am now in for it, to make a reputation and serve my country conspicuously or fail. I must not, shall not, do the latter. I must have St. Louis—then Huzza!"[14]

After waiting for McCulloch to join him, Van Dorn grew frustrated and decided to act with what he had on March 7. Around 9 a.m. he ordered Price to attack the Union position close to Elkhorn Tavern, and despite Price being wounded they had succeeded in pushing the Union forces back by nightfall, cutting Curtis' lines of communication. Meanwhile, McCulloch, under orders from Van Dorn to take a different route and hurry his march, had engaged part of Curtis' defenses. Early on in the fighting McCulloch and Brig. Gen. James M. McIntosh were killed, leaving no commander there to organize an effective attack.[20] When Van Dorn learned of the problems with his right wing, he renewed Price's attacks, saying "Then we must press them the harder," and the Confederates pushed Curtis back.[21] That night the junction of Price and what remained of McCulloch's men was made, and Van Dorn pondered his next move.[19] With his supplies and ammunition 15 miles (24 km) away and the Union force between them, Van Dorn maintained his position.[21]

The following day, March 8, showed Curtis and his command in an even stronger position, about a mile back from where they were on March 7. Van Dorn had his men arranged defensively in front of Pea Ridge Mountain, and when it was light enough he ordered the last of his artillery's ammunition fired at the Union position, to see what the Federals would do. The Union artillery answered back and knocked out most of Van Dorn's guns.[22] Curtis then counterattacked and routed the Confederates, mostly without actual contact between the opposing infantries. Van Dorn decided to withdraw south, retreating through sparse country for a week and his men living off what little they got from the few inhabitants of the region. The Army of the West finally reunited with their supplies south of the Boston Mountains.[23] In his official report Van Dorn described his summary of the events at Pea Ridge:

I attempted first to beat the enemy at Elkhorn, but a series of accidents entirely unforeseen and not under my control and a badly-disciplined army defeated my intentions. The death of McCulloch and Mcintosh and the capture of Hebert left me without an officer to command the right wing, which was thrown into utter confusion, and the strong position of the enemy the second day left me no alternative but to retire from the contest.[24]

Casualties from this battle have never been fully agreed upon. The figures given by most military historians are about 1,000 to 1,200 total Federal soldiers and around 2,000 Confederate.[25] However, Van Dorn detailed significantly different numbers in his official reports. He stated losses of about 800 killed with 1,000 to 1,200 wounded and 300 prisoners (about 2,300 total) for the Union, and only 800 to 1,000 killed and wounded and between 200 and 300 prisoners (about 1,300 total) from his army.[24]

The Confederate defeat at this battle, coupled with Van Dorn's army being ordered across the Mississippi River to bolster the Army of Tennessee, enabled the Union to control the entire state of Missouri and threaten the heart of Arkansas, left virtually defenseless without Van Dorn's forces.[26] Despite the loss at Pea Ridge, the Confederate Congress would vote its thanks "for their valor, skill, and good conduct in the battle of Elkhorn in the states of Arkansas" to Van Dorn and his men on April 21.[4] In his report on March 18 to Judah P. Benjamin, then the Confederate Secretary of War, Van Dorn refuted suffering a loss, saying "I was not defeated, but only foiled in my intentions. I am yet sanguine of success, and will not cease to repeat my blows whenever the opportunity is offered."[24]

Second Corinth

The performance of Van Dorn at the Second Battle of Corinth that autumn led to another Union Army victory. As at Pea Ridge, Van Dorn did well in the early stages of the battle on October 1–2, 1862, combining with Price's men and prudently placing his force that now was roughly equal in size to the Federals at about 22,000 soldiers. However, Van Dorn failed to reconnoiter the Union defenses, and his attack on Brig. Gen. William S. Rosecrans' strong defensive position at Corinth, Mississippi, on October 3 was bloodily repulsed.[27]

On October 4–5 his command was "roughly handled" along the Hatchie River by Union soldiers led by Brig. Gens. Stephen A. Hurlbut and Edward Ord. However, Rosecrans' lack of an aggressive pursuit allowed what was left of Van Dorn's men to escape.[27] Total casualties for the Second Battle of Corinth totaled 2,520 (355 killed, 1,841 wounded, 324 missing) for the Union, and 4,233 (473 killed, 1,997 wounded, 1,763 captured/missing) for the Confederates.

After the battle Van Dorn ordered a retreat, falling back through Abbeville, Oxford, and Water Valley, Mississippi, where he and his staff were nearly captured on December 4, then on to Coffeeville, Mississippi, constantly skirmishing with Federal cavalry. on December 4. Two days later Van Dorn halted the retreat at Grenada.[28] Following the defeat at Corinth, Van Dorn was sent before a court of inquiry to answer for his performance there. Though he was acquitted of the charges against him,[29] Van Dorn would never be trusted with the command of an army again,[14] and he was subsequently relieved of his district command.[28]

Return to cavalry service

Holly Springs Raid

Van Dorn proved to be more effective as a cavalry commander, leading the Holly Springs Raid, which seriously disrupted Ulysses S. Grant's first Vicksburg Campaign plans.[27] Van Dorn was upset at being relieved by General John C. Pemberton at Vicksburg,[30] and wanted to regain his honor. Obtaining Pemberton's permission, Van Dorn planned a secret raid against Grant, not even telling his soldiers. On December 16, 1862, Van Dorn, with 2,500 fighting cavalry[31] left Grenada, fording the Yalobusha, riding northeast. [32] At dawn, December 20, Van Dorn and his lightning cavalry struck Holly Springs, capturing 1,500 sleepy Union soldiers, while destroying at least $1,500,000 worth of Union supplies.[2][33] Union post commander Colonel Robert C. Murphy was captured. Six hundred Illinois Union cavalry cut loose and escaped Van Dorn's wrath.[34] Local Confederate women at Holly Springs cheered Van Dorn proclaiming "the Glorious Twentieth".[35]

Grant had not been caught unaware of Van Dorn's raid. Grant had placed his Union cavalry on 24-hour watch to protect his supply line.[36] Union cavalry commander T. Lyle Dickie had warned Grant that Van Dorn had left Grenada and was headed northeast.[36] Grant had warned by telegraph post commanders of Van Dorn's raid, but to no avail. Colonel Murphy had been warned by Grant twice Van Dorn was headed his way, but Murphy did nothing to prepare for battle.[37] Grant's wife Julia and son Jesse were not in Holly Springs at the time of Van Dorn's raid. Julia and Jesse had left Holly Springs the night before to meet with Grant at Oxford.[38]

Ulysses S. Grant

Van Dorn's raid directly coincided with Grant's General Order No. 11, issued by Grant less than 72 hours earlier, that expelled Jews as a class from Grant's military district.[39] Grant had believed Jewish traders violated cotton trade regulations by the U.S. Treasury Department. Van Dorn's raid destroyed and disrupted Union communications lines. Additionally, Confederate General Bedford Forrest, on an earlier raid starting December 10, had destroyed communication lines and fifty miles of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad, behind Grant's front line. [40] Van Dorn's cavalry raid delayed the implementation of Grant's General Order No. 11 for weeks, saving many Jews from potential expulsion.[39]

After sacking Holly Springs, Van Dorn and his men then followed the Mobile and Ohio Railroad, fought unsuccessfully at Davis's Mills, skirmished near Middleburg, Tennessee, passed around Bolivar, and returned to their Grenada base by December 28.[28] The successful raid helped Van Dorn regain his reputation that was lost at Second Corinth.[41]

The attacks of both Van Dorn and Forrest caused Grant to withdraw his troops to Grand Junction, Tennessee, his Union army living off the countryside.[42] With the telegraph lines destroyed by Van Dorn and Forrest, Grant could not communicate his withdrawal to Sherman, who was repulsed at Chickisaw Bluffs on December 29.[43] Although Grant was humiliated by devastating raids of both Van Dorn and Forrest, he was not fired, protected by Grant's previous victories at Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, Shiloh, Iuka, and Corinth.[44] President Lincoln revoked Grant's controversial General Order No. 11. Although Grant was thwarted in his first attempt to capture Vicksburg, saved by Van Dorn, Grant's second attempt was successful, capturing Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. [45] Grant never forgot the sting of the Confederate cavalry, inflicted by Van Dorn and Forrest, and he later incorporated the Union Cavalry as a separate fighting unit, under Union General Phil Sheridan, during the Overland Campaign, in 1865.[46]

Appointed cavalry commander

On January 13, 1863, Van Dorn was appointed to command all cavalry in the Department of Mississippi & East Louisiana, and then was ordered by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston to join the Army of Tennessee, operating in Middle Tennessee. Van Dorn and his force left Tupelo, Mississippi, went through Florence, and reached the army on February 20 at Columbia, Tennessee. Van Dorn set up his headquarters at Spring Hill at White Hall and assumed command of all of the surrounding cavalry from there. He was ordered by the army commander, Gen. Braxton Bragg, to protect and scout the left of the army, screening against Union cavalry.[47]

Battle of Thompson's Station

Bedford Forrest

Van Dorn was also successful at Battle of Thompson's Station, on March 5, 1863. There a Union brigade, under Col. John Coburn, left Franklin to reconnoiter to the south. About four miles short of Spring Hill Coburn attacked a Confederate force composed of two regiments and was repulsed. Van Dorn then sent Brig. Gen. William Hicks Jackson's dismounted soldiers to make a direct frontal assault, while Brig. Gen. Bedford Forrest's troopers went around Coburn's left and into the Federal rear. After three charges were beaten back, Jackson finally carried the Union position as Forrest captured Coburn's wagon train, blocking the road to Columbia and the only Union escape route. Nearly out of ammunition as well as surrounded, Coburn surrendered.

First Battle of Franklin

On March 16, 1863, Van Dorn was given command of the cavalry corps of the Army of Tennessee[48] and fought his last fight April 10 at the First Battle of Franklin, skirmishing with the cavalry of Gordon Granger and losing 137 men to Granger's 100 or so. This minor action caused Van Dorn to halt his movement and rethink his plans, and subsequently he returned in the Spring Hill area.[27] Bedford Forrest, commanding one of Van Dorn's cavalry brigades, criticized his judgement as a general, and an angered Van Dorn challenged Forrest to a duel. However, Forrest talked him out of it and so prevented an altercation that may have been fatal to both of them.

Alleged affair

It was Van Dorn's reputation as a womanizer, not a Union bullet, that led to his death. Van Dorn made his headquarters in the home of Martin Cheairs in Spring Hill, Tennessee. Ever the ladies' man, he attracted the attention of Jesse Helen Kissack Peters, the wife of a prominent local physician, Dr. George Peters, who was taking time away from practicing medicine to serve in the state legislature. Mrs. Peters, the fourth wife of Dr. Peters and nearly 25 years his junior, was described by locals as "bored" by her husband's long journeys away from home. Gossip quickly spread around town about Van Dorn's visits to Mrs. Peters' home and their frequent unchaperoned carriage rides together.[49][48] Dr. Peters returned home on April 12 and was immediately confronted with the mockery of local townsfolk that he was a cuckold. Peters let it be known that he would shoot Van Dorn or any of his staff who set foot on his property. Eventually, the doctor hid outside the house at night where he saw Van Dorn arrive. Peters rushed inside and found Van Dorn and his wife in a passionate embrace. He threatened to shoot Van Dorn on the spot, but the general pleaded for mercy if he would spare Mrs. Peters from any responsibility in the incident. Dr. Peters accepted this offer.[50]

Homicide

Nonetheless, a few weeks later, on the morning of May 7, Dr. Peters arrived outside the Cheairs mansion. Van Dorn's staff recognized him, as he frequently stopped to obtain passes through the Confederate lines, and let him inside. Peters walked into Van Dorn's office, where the general was busy writing at his desk, pulled out a pistol, and shot him in the back of the head. A few minutes later, the daughter of Martin Cheairs ran outside announcing that Peters had shot Van Dorn. The general's staff found him unconscious, but still alive. However, nothing could be done to save Van Dorn and he died four hours later, having never regained consciousness. The nature of Van Dorn's death was similar to the death of President Lincoln two years later in that the small caliber pistol round had traversed through his brain and lodged behind his forehead. Van Dorn's brain swelled from intracranial pressure, leading to a cerebral herniation and eventual cardiac and respiratory arrest. Peters was later arrested by Confederate authorities, but was never brought to trial for the killing.[48] In defense of his actions, Dr. Peters stated that Van Dorn had "violated the sanctity of his home." Condemnation of Van Dorn in the South was widespread, as the code of chivalry ran strong in the region, and Confederate general St. John Liddell, a brigadier in the Army of Tennessee, said that there was little sympathy to be had for him.[51]

Aftermath

A number of conspiracy theories have been spoken about Van Dorn's death, including the possibility that Dr. Peters was motivated more by politics than the sanctity of his marriage or his unmarried 15 year old daughter's pregnancy.[52][53][54] As a state legislator, Peters had earlier taken the oath of loyalty to the United States in Memphis, and although he divorced his wife soon after her affair was revealed, the couple later reconciled and Peters received a mysterious land grant in Arkansas. Van Dorn's sister Emily later wrote a memoir defending her brother and blaming Peters's Union allegiance in the war as the real reason for shooting him.[55]

General Van Dorn is one of the three major generals in the American Civil War who died violently but from private problems. The others were Union Major General William "Bull" Nelson, shot as the result of a feud with then Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis in September 1862; and Confederate Major General John A. Wharton, shot as the result of an argument with Colonel George Wythe Baylor in April 1865.[56]

Van Dorn's body was initially transported and buried in the graveyard of his wife's family in Alabama, but at his sister's request returned to Mississippi and reburied next to their father at Wintergreen Cemetery in Port Gibson.[48][57]

Van Dorn's childhood home, the Van Dorn House in Port Gibson, Mississippi, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Assessment

Controversial throughout his life, Van Dorn as a military commander was an able leader of small to medium groups of soldiers, particularly cavalry, but was out of his depth with larger commands. Military historian David L. Bongard described him as "aggressive, brave, and energetic but lacked the spark of genius necessary for successful high command in combat."[27] Military historian Richard P. Weinert summarized Van Dorn: "A brilliant cavalry officer, he was a disappointment in command of large combined forces."[58]

Military historian and biographer John C. Fredriksen described him as "a brave and capable soldier, but he proved somewhat lacking in administrative ability." Fredriksen goes on to say that Van Dorn belonged in cavalry command, stating him to be "back in his element" and "demonstrated flashes of brilliance" with that branch of the service. Fredriksen also believed Van Dorn's successes at Holly Springs and Thompson's Station in the spring of 1863 made him one of the leading cavalry leaders in the Confederacy, and notes that his death cost the service a "useful leader at a critical juncture of the Vicksburg campaign" and also states that Van Dorn was the senior major general in the Confederate States Army at the time of his murder.[59]

Physically short,[60] impulsive, and highly emotional, Van Dorn was also a noted painter, writer of poetry, was respected for his skill at riding a horse, and also known for his love of women. A reporter at the time dubbed him "the terror of ugly husbands" shortly before Van Dorn's murder.[14]

Honors

Port Gibson monument (1906)

Van Dorn was a native of Port Gibson, Mississippi. In 1906, a Confederate monument was dedicated at Port Gibson, built by the Daughters of the Confederacy of Claiborne County. The monument contains a portrait statue of Van Dorn at the top. [61]

Camp Van Dorn (1942–1945)

During WWII, in February 1942, construction began on an emergency 41,844-acre training camp in southern Mississippi, south of Centreville. US ground troops were trained at the base to serve as division soldiers in the European Theatre of the war. The camp was named in honor of Van Dorn and existed from 1942 to December 31, 1945. In June 1943, controversy ensued when rumors spread that more than 1,200 members of the African American 364th division were killed at the camp.[62][63] Author Carol Case said, in Case's August 1998 book The Slaughter: An American Atrocity, there was an actual massacre of black troops. In 1999, the US Army Center of Military History investigation said there was “no documentary evidence whatsoever that any unusual or inexplicable loss of personnel occurred.”[63] In May 1943, one 364th black soldier from Camp Van Dorn, was killed on a street in Centreville, for not having a military pass.[62] Black soldiers were known to complain about Jim Crow laws and the arrogance of white civilians.[62]

See also

- List of American Civil War generals (Confederate)

- CSS General Earl Van Dorn, a side-wheel river steamer named for the general

- Van Dorn battle flag

Notes

- Chernow 2017, p. 240.

- "Earl Van Dorn (1820–1863)". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- 1860 U.S. Federal Census for Garrison, Mason, Texas, family 93 p. 1 of 4, available on ancestry.com

- Eicher, Civil War High Commands, p. 542.

- Foote, Vol. I, p. 278.

- "Earl Van Dorn". Corpus Christi Public Libraries. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- Dupuy, p. 771.

- Fredrickson, p. 21.

- Foote, Vol. I, p. 278. One of the three vessels was the SS Star of the West, known for its role with Ft. Sumter in January 1861.

- Weinert, p. 26.

- Foote, Vol. I, p. 278. These exploits were heralded in Southern print of the time, and a Northern editor offered $5,000.00 USD for Van Dorn's head, twice the going rate for Beauregard.

- Weinert, p. 25.

- Wright, p. 22 "Appointed from Mississippi, September 19, 1861, to rank from same date" Confirmed by the Confederate Senate on December 13, 1861.

- "Earl Van Dorn". National Park Service. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- Eicher, Civil War High Commands, p. 884

- Foote, Vol. I., p. 281.

- Foote, Vol.I., p. 279.

- Foote, Vol. I., p. 283.

- Foote, p. 287.

- Foote, Vol. I., p. 286.

- Cannan, p. 45.

- Foote, Vol. I., p. 290.

- Foote, Vol. I., p. 291.

- "Reports of Van Dorn concerning Pea Ridge". Civil War Archive. Archived from the original on August 7, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- Kennedy, p. 37. cites 1,000 Federal soldiers and 2,000 Confederate; Eicher, Longest Night, p. 193, cites 1,384 Union and "about 800 Confederate"; Johnson, p. 337, also cites 1,384 Union and matches Van Dorn's Confederate estimate; Foote, Vol. I., p. 292: Curtis reported 203 dead, 980 wounded, 201 missing, totaling 1,384.

- Foote, Vol.I., p. 292.

- Dupuy, p. 772.

- Weinert, p. 36.

- NPS bio. Charges were: negligence of duty, disregarding the welfare of his men, and not adequately planning the campaign.

- White 2016, pp. 248–249.

- Chernow, 2017 & White 2016.

- Miller, 2019 & White 2016, p. 225.

- Chernow 2017, p. 239; Miller 2019, p. 225.

- Miller 2019, p. 245.

- White 2016, p. 249.

- Miller 2019, p. 226.

- Miller 2019, pp. 225–226.

- Miller 2019, p. 225.

- Sarna 2012.

- Smith 2001, pp. 223–224.

- Chernow 2017, p. 239.

- Smith 2001, p. 224.

- Smith 2001, pp. 224–225.

- Miller 2019, p. 227.

- Smith 2001, pp. 245–247.

- Smith 2001, p. 299.

- Weinert, pp. 36–37.

- Eicher, Civil War High Commands, p. 543.

- Primary records instead show the husband was Dr. George B. Peters. See also Alethea Sayers, "Road to Dishonor: Earl Van Dorn," http://ehistory.osu.edu/uscw/features/articles/9907/vandorn.cfm, n.d.

- David Logsdon. "Earl Van Dorn". Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- Warner, p. 315.

- "Mitcham's Abbeville blog".

- "Historynet blog".

- "Tennessee Encyclopeia".

- https://archive.org/details/soldiershonorwit00milliala

- Eicher, Civil War High Commands, pp. 405, 563.

- "Earl Van Dorn". Texas St. Historical Assn. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- Weinert, p. 37.

- Fredriksen, pp. 787–88.

- Foote, Vol. I, p. 277. height given as 5ft. 5in. tall, or 2 inches above Napoleon

- Rozier, Alex (October 3, 2018), Why a Confederate monument endures in majority-black Port Gibson, Claiborne County, retrieved December 17, 2020

- Clifford 1999.

- Camp Van Dorn.

References

- Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-487-6.

- Cannan, John, ed., War in the West: Shiloh to Vicksburg, 1862–1863, W.H. Smith Publishers, 1990, ISBN 0-8317-3084-6.

- Dupuy, Trevor N., Johnson, Curt, and Bongard, David L., Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography, Castle Books, 1992, 1st Ed., ISBN 0-7858-0437-4.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 978-0-684-84944-7.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 1, Fort Sumter to Perryville. New York: Random House, 1958. ISBN 978-0-394-41948-0.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 2, Fredericksburg to Meridian. New York: Random House, 1958. ISBN 978-0-394-41951-0.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 3, Red River to Appomattox. New York: Random House, 1974. ISBN 978-0-394-74622-7.

- Fredriksen, John C., Civil War Almanac, Checkmark Books/Infobase Publishing, 2008, ISBN 978-0-8160-7554-6.

- Johnson, Robert Underwood and Clarence C. Buel, eds. Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. 1 New York: Century Co., 1884–1888. OCLC 2048818. (Later edition: New York: Castle Books, 1956 (by arrangement with A.S. Barnes & Co., Inc.).}

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Miller, Donald L. (2019). Vicksburg: Grant's Campaign That Broke the Confederacy. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4137-0.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2001). Grant. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

- Weinert, Jr., Richard P. The Confederate Regular Army. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing, 1991, ISBN 978-0-942597-27-1.

- White, Ronald C. (2016). American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-58836-992-5.

- Wright, Marcus J., General Officers of the Confederate Army: Officers of the Executive Departments of the Confederate States, Members of the Confederate Congress by States. Mattituck, NY: J. M. Carroll & Co., 1983. ISBN 0-8488-0009-5. First published 1911 by Neale Publishing Co.

Online

- Clifford, James O. (February 14, 1999). "Were Blacks in Troubled WWII Regiment Sent to Front as Punishment?". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- "Camp Van Dorn". Mississippi Encyclopedia. Center for Study of Southern Culture. April 13, 2018. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- Sarna, Jonathan D. (March 23, 2012). "When General Grant Expelled the Jews". jewishweek.timesofisrael.com. The New York Jewish Week. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- www.library.ci.corpus-christi.tx.us Online military biography of Van Dorn.

- encyclopediaofarkansas.net Encyclopedia Of Arkansas biography of Van Dorn.

- tennesseeencyclopedia.net Tennessee Encyclopedia biography of Van Dorn.

- U.S. National Park Service biography of Van Dorn.

- www.civilwararchive.com Copies of Van Dorn's official reports concerning Pea Ridge.

- www.tshaonline.org Texas St. Historical Assn. biography of Van Dorn.

Further reading

- Carter, Arthur B., The Tarnished Cavalier: Major General Earl Van Dorn, C.S.A., University of Tennessee Press, 1999, ISBN 1-57233-047-3.

- Cozzens, Peter, The Darkest Days of the War: The Battles of Iuka and Corinth, University of North Carolina Press, 1997, ISBN 0-8078-5783-1.

- DeBlack, Thomas R., With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874, University of Arkansas Press, 2003, ISBN 1-55728-740-6.

- Hartje, Robert George, Van Dorn: The Life and Times of a Confederate General, Vanderbilt University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-8265-1254-2.

- Lowe, Richard, "Van Dorn's Raid on Holly Springs, December 1862" Journal of Mississippi History, #61, 1999, pp. 59–71.

- Shea, William & Hess, Earl, Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West, University of North Carolina Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8078-4669-4.

- Winschel, Terrance J., "Earl Van Dorn: From West Point to Mexico" Mississippi History 62, no. 3, 2000, pp. 179–97.

External links

- Works by or about Earl Van Dorn at Internet Archive

- civilwarhome.com Civil War Home site biography of Van Dorn.

- blueandgraytrail.com Georgia's Blue and Gray Trail site biography of Van Dorn.

- civilwar.org Civil War Preservation Trust site biography of Van Dorn.

- Earl Van Dorn at Find a Grave

- historyofwar.org Military History Encyclopedia on the Web site biography of Van Dorn.

- Correspondences of Earl Van Dorn during the American Civil War – held in the Walter Havighurst Special Collections, Miami University