Earl of Ulster

The title of Earl of Ulster has been created six times in the Peerage of Ireland and twice Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since 1928, the title has been held by the Duke of Gloucester and is used as a courtesy title by the Duke's eldest son, currently Alexander Windsor, Earl of Ulster. The wife of the Earl of Ulster is known as the Countess of Ulster. Ulster, one of the four traditional provinces of Ireland, consists of nine counties, six of which make up Northern Ireland, the remainder are in Ireland.

.svg.png.webp)

History

King Henry II of England granted three Palatinates or seigniories in Ireland to Norman nobles during the Norman invasion of Ireland, that are considered to be equivalents of either earldoms or lordships by modern historians. Richard de Clare, Count Striguil, a Norman-Welsh knight known as Strongbow, was created Earl of Leinster, and the Anglo-Norman Sir Hugh de Lacy was created Earl of Meath. In 1181, King Henry II created Sir John de Courcy Earl of Ulster by patent. He was later also created Lord of Connaught and quickly became a rival of the De Lacys.[2] No record of his enrollment exists, but de Courcy enjoyed the grant of Ulster as an earldom, according to 19th-century analysis of deeds de Courcy executed that survived in patent rolls (the earliest of which dates to 1201).[3]

Though Ulster covers one-sixth of Ireland, making it among the largest land grants in Ireland, De Courcy began aggressively seizing more land in Ireland without permission, drawing the ire of King John of England. Hugh de Lacy the younger, son of the Earl of Meath, accused de Courcy of neglecting to pay homage to King John. The king sent a letter to the feudal barons of Ulster — allies of de Courcy – informing them that if they did not convince their lord to pay proper homage, all their land would be seized.[3] According to the Four Masters, in 1203, Hugh de Lacy the younger, along with a contingent of English soldiers from Meath, marched on Ulaid and expelled de Courcy. A bloody battle between the two sides ensued at place called Dundaleathglass (possibly Down, but de Courcy escaped following defeat. In 1204, the de Lacy forces drove de Courcy, "the plunderer of churches and territories," into Tyrone, where he sought protection from the Clan Owen, but the English of Ulaid chased him as far as Carrickfergus, Antrim. On Good Friday 1204, de Courcy was praying at the Church of Downpatrick (from which he had expelled, in 1177, the Augustinian monks settled there by St Malachy in 1124, replacing them with Benedictine monks). According to the account of his capture, the unarmed de Courcy managed to take a weapon from de Lacy's men and killed 13 of the men before he was finally subdued and sent to England where he was imprisoned in the Tower of London.[4][5] Though he eventually returned to royal favor, de Courcy never returned to Ireland.

De Lacy's lands and title were forfeited, and de Lacy was created the Earl of Ulster with the transfer of de Courcy's rights. The creation specifically granted Hugh de Lacy the right to everything John de Courcy possessed on the day of the battle, with exception the churches, which remained with the crown:[3]

"The King to Meyler Fitz Henry, &c. and the Barons of Ireland, &c.

Know ye, that we have given and granted to Hugh de Lascy, for his homage and service, the land of Ulster, with the appurtenances, to have and to hold as John de Curcy held the same the day on which the same Hugh overcame him in the field, or on the day preceding: SAVING however to us the crosses of the same land. And know ye, that we do retain with us the aforesaid Hugh, and are leading him with us in our service; and therefore to you we command that his land and all his you preserve, maintain and defend as our demesne. Witness myself, at Windsor, the 2nd day of May." — Rotuli Litterarum Patentium in Turri Londinensi asservati 6 John[3]

An additional grant the following year confirmed granted to him the "whole land of Ulster" et hæredibus suis (with remainder to his heirs). He died in 1243, leaving only one legitimate daughter, Lady Maud de Lacy. Upon her marriage to Walter de Burgh, Lord of Connaught in 1264, de Burgh was created Earl of Ulster in right of his wife.[2][6][7][8]

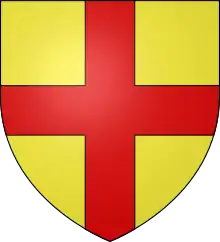

The Burgh coat of arms (or a cross gules) were adopted as the flag of Ulster, though the title passed through the female line out of the family and eventually merged with the crown. After the third earl was murdered at age 20 (leading to the Burke Civil War), he left only a daughter, Elizabeth de Burgh, 4th Countess of Ulster. She married Lionel of Antwerp, second surviving son of King Edward III, who held the title jure uxoris. Their only child Philippa became Countess of Ulster suo jure while her husband, Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March, held the title jure uxoris.[9]

After the death of Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March and 7th Earl of Ulster, the earldoms and estates were left to his nephew, Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York, the son of Edmund's elder sister Anne de Mortimer. Along with his land and titles, Richard also inherited Mortimer's claim to the throne, which eventually led to the Wars of the Roses. After the Yorkist victory, Richard's son Edward of York was crowned Edward IV in 4 March 1461, and the Earldom of Ulster merged with the crown.

The title of Earl of Ulster has subsequently been recreated six times for members of the royal family. The current incarnation of the title dates to 31 March 1928, when Prince Henry, the third son of King George V and Queen Mary, was simultaneously created Duke of Gloucester, Earl of Ulster and Baron Culloden in the Peerage of the United Kingdom.[6]

Earls Palatine of Ulster (1181)

- Sir John de Courcy, forfeit 1204[2]

Earls of Ulster, Peerage of Ireland, First Creation (1205)

- Hugh de Lacy, 1st Earl of Ulster (1176–1243)

Earls of Ulster, Peerage of Ireland, Second Creation (1264)

- Walter de Burgh, 1st Earl of Ulster (died 1271)

- Richard Óg de Burgh, 2nd Earl of Ulster (1259–1326)

- William Donn de Burgh, 3rd Earl of Ulster (1312–1333)

- Elizabeth de Burgh, Duchess of Clarence, 4th Countess of Ulster (1332–1363)

- Philippa, Countess of March, 5th Countess of Ulster (1355–1382)

- Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March and 6th Earl of Ulster (1374–1398)

- Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March and 7th Earl of Ulster (1391–1425)

- Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York, 8th Earl of Ulster (1411–1460)

- Edward of York, 4th Duke of York, 9th Earl of Ulster (1442–1483), merged in crown 1461

Earls of Ulster, Peerage of Ireland, Third Creation (1659)

- James Stuart, Duke of York and Albany (1633–1701), merged in crown 1685

Earls of Ulster, Peerage of Ireland, Fourth Creation (1716)

Earls of Ulster, Peerage of Ireland, Fifth Creation (1760)

- Prince Edward, Duke of York and Albany (1739–1767)

Earls of Ulster, Peerage of Ireland, Sixth Creation (1784)

- Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (1763–1827)

Earls of Ulster, Peerage of the United Kingdom, First Creation (1866)

- Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh (1844–1900)

Earls of Ulster, Peerage of the United Kingdom, Second Creation (1928)

- Prince Henry, 1st Duke of Gloucester (1900–1974)

- Prince Richard, 2nd Duke of Gloucester (born 1944)

- Alexander Windsor (born 1974), Prince Richard's eldest son, is the heir-apparent to the dukedom, and, as such, uses "Earl of Ulster" as a courtesy title.

See also

References

- Doyle, James William Edmund (1886). The Official Baronage of England. Longmans, Green. p. 469. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Berry, MRIA, Major R.G. (January 1906). "The Whites of Dufferin and their Connection". Ulster Journal of Archaeology. Ulster Archaeological Society. XII (1): 122. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Lynch, William (1830). A View of the legal institutions, honorary hereditary offices, and Feudal Baronies, established in Ireland, during the reign of Henry II., etc. pp. 144–145. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "On the Account of the Life and Acts of Saint Patrick". Archaeologia Scotica: Transactions of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland: 250. 1822.

- O'Clery, Michael (1845). "The annals of Ireland, tr. from the orig. Irish of the Four masters by O. Connellan": 31. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Banks, Thomas Christopher (1843). Baronia Anglica Concentrata. p. 206. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Burke, John (1846). A General and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerages of England, Ireland, and Scotland, extinct, dormant, and in abeyance. Henry Colburn. p. PA300. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- O'Donovan, John (1856). Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland. Hodges, Smith and Company. p. 393. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Recent Booklplates". Journal of the Ex Libris Society. A. & C. Black. VI (1): 138. January 1896.