Henry II of England

Henry II (5 March 1133 – 6 July 1189), also known as Henry Curtmantle (French: Court-manteau), Henry FitzEmpress or Henry Plantagenet, was King of England from 1154 to his death. He was the first king of the House of Plantagenet. King Louis VII of France made him Duke of Normandy in 1150. Henry became Count of Anjou and Maine upon the death of his father, Count Geoffrey V, in 1151. His marriage in 1152 to Eleanor of Aquitaine, whose marriage to Louis VII had recently been annulled, made him Duke of Aquitaine. He became Count of Nantes by treaty in 1185. Before he was 40 he controlled England, large parts of Wales, the eastern half of Ireland and the western half of France—an area that would later come to be called the Angevin Empire. At various times, Henry also partially controlled Scotland, Wales and the Duchy of Brittany.

| Henry II | |

|---|---|

Detail from Henry II's effigy in Fontevraud Abbey, Fontevraud-l'Abbaye | |

| King of England | |

| Reign | 19 December 1154 – 6 July 1189 |

| Coronation | 19 December 1154 |

| Predecessor | Stephen |

| Successor | Richard I |

| Junior king | Henry the Young King |

| Born | 5 March 1133 Le Mans, Maine, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 6 July 1189 (aged 56) Chinon Castle, Chinon, Indre-et-Loire, Kingdom of France |

| Burial | Fontevraud Abbey, Anjou, France |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Plantagenet/Angevin[nb 1] |

| Father | Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou |

| Mother | Empress Matilda |

Henry became actively involved by the age of 14 in the efforts of his mother Matilda, daughter of Henry I of England, to claim the throne of England, then occupied by Stephen of Blois. Stephen agreed to a peace treaty after Henry's military expedition to England in 1153, and Henry inherited the kingdom on Stephen's death a year later. Henry was an energetic and sometimes ruthless ruler, driven by a desire to restore the lands and privileges of his grandfather Henry I. During the early years of his reign the younger Henry restored the royal administration in England, re-established hegemony over Wales and gained full control over his lands in Anjou, Maine and Touraine. Henry's desire to reform the relationship with the Church led to conflict with his former friend Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury. This controversy lasted for much of the 1160s and resulted in Becket's murder in 1170. Henry soon came into conflict with Louis VII, and the two rulers fought what has been termed a "cold war" over several decades. Henry expanded his empire at Louis's expense, taking Brittany and pushing east into central France and south into Toulouse; despite numerous peace conferences and treaties, no lasting agreement was reached.

Henry and Eleanor had eight children—three daughters and five sons. Three of his sons would be king, though Henry the Young King was named his father's co-ruler rather than a stand-alone king. As the sons grew up, tensions over the future inheritance of the empire began to emerge, encouraged by Louis and his son King Philip II. In 1173 Henry's heir apparent, "Young Henry", rebelled in protest; he was joined by his brothers Richard (later a king) and Geoffrey and by their mother, Eleanor. France, Scotland, Brittany, Flanders, and Boulogne allied themselves with the rebels. The Great Revolt was only defeated by Henry's vigorous military action and talented local commanders, many of them "new men" appointed for their loyalty and administrative skills. Young Henry and Geoffrey revolted again in 1183, resulting in Young Henry's death. The Norman invasion of Ireland provided lands for his youngest son John (later a king), but Henry struggled to find ways to satisfy all his sons' desires for land and immediate power. By 1189, Young Henry and Geoffrey were dead, and Philip successfully played on Richard's fears that Henry II would make John king, leading to a final rebellion. Decisively defeated by Philip and Richard and suffering from a bleeding ulcer, Henry retreated to Chinon Castle in Anjou. He died soon afterwards and was succeeded by Richard.

Henry's empire quickly collapsed during the reign of his son John (who succeeded Richard), but many of the changes Henry introduced during his long rule had long-term consequences. Henry's legal changes are generally considered to have laid the basis for the English Common Law, while his intervention in Brittany, Wales, and Scotland shaped the development of their societies and governmental systems. Historical interpretations of Henry's reign have changed considerably over time. In the 18th century, scholars argued that Henry was a driving force in the creation of a genuinely English monarchy and, ultimately, a unified Britain. During the Victorian expansion of the British Empire, historians were keenly interested in the formation of Henry's own empire, but they also expressed concern over his private life and treatment of Becket. Late-20th-century historians have combined British and French historical accounts of Henry, challenging earlier Anglocentric interpretations of his reign.

Early years (1133–1149)

Henry was born in Normandy at Le Mans on 5 March 1133, the eldest child of the Empress Matilda and her second husband, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou.[2] The French county of Anjou was formed in the 10th century and the Angevin rulers attempted for several centuries to extend their influence and power across France through careful marriages and political alliances.[3] In theory, the county answered to the French king, but royal power over Anjou weakened during the 11th century and the county became largely autonomous.[4]

Henry's mother was the eldest daughter of Henry I, King of England and Duke of Normandy. She was born into a powerful ruling class of Normans, who traditionally owned extensive estates in both England and Normandy, and her first husband had been the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V.[5] After her father's death in 1135, Matilda hoped to claim the English throne, but instead her cousin Stephen of Blois was crowned king and recognised as the Duke of Normandy, resulting in civil war between their rival supporters.[6] Geoffrey took advantage of the confusion to attack the Duchy of Normandy but played no direct role in the English conflict, leaving this to Matilda and her half-brother, Robert, Earl of Gloucester.[7] The war, termed the Anarchy by Victorian historians, dragged on and degenerated into stalemate.[8]

Henry most likely spent some of his earliest years in his mother's household, and accompanied Matilda to Normandy in the late 1130s.[9] Henry's later childhood, probably from the age of seven, was spent in Anjou, where he was educated by Peter of Saintes, a noted grammarian of the day.[10] In late 1142, Geoffrey decided to send the nine-year-old to Bristol, the centre of Angevin opposition to Stephen in the south-west of England, accompanied by Robert of Gloucester.[11] Although having children educated in relatives' households was common among noblemen of the period, sending Henry to England also had political benefits, as Geoffrey was coming under criticism for refusing to join the war in England.[11] For about a year, Henry lived alongside Roger of Worcester, one of Robert's sons, and was instructed by a magister, Master Matthew; Robert's household was known for its education and learning.[12] The canons of St Augustine's in Bristol also helped in Henry's education, and he remembered them with affection in later years.[13] Henry returned to Anjou in either 1143 or 1144, resuming his education under William of Conches, another famous academic.[14]

Henry returned to England in 1147, when he was fourteen.[15] Taking his immediate household and a few mercenaries, he left Normandy and landed in England, striking into Wiltshire.[15] Despite initially causing considerable panic, the expedition had little success, and Henry found himself unable to pay his forces and therefore unable to return to Normandy.[15] Neither his mother nor his uncle were prepared to support him, implying that they had not approved of the expedition in the first place.[16] Surprisingly, Henry instead turned to King Stephen, who paid the outstanding wages and thereby allowed Henry to retire gracefully. Stephen's reasons for doing so are unclear. One potential explanation is his general courtesy to a member of his extended family; another is that he was starting to consider how to end the war peacefully, and saw this as a way of building a relationship with Henry.[17] Henry intervened once again in 1149, commencing what is often termed the Henrician phase of the civil war.[18] This time, Henry planned to form a northern alliance with King David I of Scotland, Henry's great-uncle, and Ranulf of Chester, a powerful regional leader who controlled most of the north-west of England.[19] Under this alliance, Henry and Ranulf agreed to attack York, probably with help from the Scots.[20] The planned attack disintegrated after Stephen marched rapidly north to York, and Henry returned to Normandy.[21][nb 2]

Appearance and personality

Henry was said by chroniclers to be good-looking, red-haired, freckled, with a large head; he had a short, stocky body and was bow-legged from riding.[22] Often he was scruffily dressed.[23] Not as reserved as his mother, nor as charming as his father, Henry was famous for his energy and drive.[24] He was also infamous for his piercing stare, bullying, bursts of temper and, on occasion, his sullen refusal to speak at all.[25] Some of these outbursts may have been theatrical and for effect.[26][nb 3] Henry was said to have understood a wide range of languages, including English, but spoke only Latin and French.[27][nb 4] In his youth Henry enjoyed warfare, hunting and other adventurous pursuits; as the years went by he put increasing energy into judicial and administrative affairs and became more cautious, but throughout his life he was energetic and frequently impulsive.[29]

Henry had a passionate desire to rebuild his control of the territories that his grandfather, Henry I, had once governed.[30] He may well have been influenced by his mother in this regard, as Matilda also had a strong sense of ancestral rights and privileges.[31] Henry took back territories, regained estates, and re-established influence over the smaller lords that had once provided what historian John Gillingham describes as a "protective ring" around his core territories.[32] He was probably the first king of England to use a heraldic design: a signet ring with either a leopard or a lion engraved on it. The design would be altered in later generations to form the Royal Arms of England.[33]

Early reign (1150–1162)

Acquisition of Normandy, Anjou, and Aquitaine

By the late 1140s the active phase of the civil war was over, barring the occasional outbreak of fighting.[34] Many of the barons were making individual peace agreements with each other to secure their war gains and it increasingly appeared as though the English church was considering promoting a peace treaty.[35] On Louis VII's return from the Second Crusade in 1149, he became concerned about the growth of Geoffrey's power and the potential threat to his own possessions, especially if Henry could acquire the English crown.[36] In 1150, Geoffrey made Henry the Duke of Normandy and Louis responded by putting forward King Stephen's son Eustace as the rightful heir to the duchy and launching a military campaign to remove Henry from the province.[37][nb 5] Henry's father advised him to come to terms with Louis and peace was made between them in August 1151 after mediation by Bernard of Clairvaux.[39] Under the settlement Henry did homage to Louis for Normandy, accepting Louis as his feudal lord, and gave him the disputed lands of the Norman Vexin; in return, Louis recognised him as duke.[39]

Geoffrey died in September 1151, and Henry postponed his plans to return to England, as he first needed to ensure that his succession, particularly in Anjou, was secure.[39] At around this time he was also probably secretly planning his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, then still the wife of Louis.[39] Eleanor was the Duchess of Aquitaine, a land in the south of France, and was considered beautiful, lively and controversial, but had not borne Louis any sons.[40] Louis had the marriage annulled and Henry married Eleanor eight weeks later on 18 May.[39][nb 6] The marriage instantly reignited Henry's tensions with Louis: it was considered an insult, it ran counter to feudal practice and it threatened the inheritance of Louis and Eleanor's two daughters, Marie and Alix, who might otherwise have had claims to Aquitaine on Eleanor's death. With his new lands, Henry now possessed a much larger proportion of France than Louis.[42] Louis organised a coalition against Henry, including Stephen, Eustace, Henry I, Count of Champagne, and Robert, Count of Perche.[43] Louis's alliance was joined by Henry's younger brother, Geoffrey, who rose in revolt, claiming that Henry had dispossessed him of his inheritance.[44] Their father's plans for the inheritance of his lands had been ambiguous, making the veracity of Geoffrey's claims hard to assess.[45] Contemporaneous accounts suggest he left the main castles in Poitou to Geoffrey, implying that he may have intended Henry to retain Normandy and Anjou but not Poitou.[46][nb 7]

Fighting immediately broke out again along the Normandy borders, where Henry of Champagne and Robert captured the town of Neufmarché-sur-Epte.[48] Louis's forces moved to attack Aquitaine.[49] Stephen responded by placing Wallingford Castle, a key fortress loyal to Henry along the Thames Valley, under siege, possibly in an attempt to force a successful end to the English conflict while Henry was still fighting for his territories in France.[50] Henry moved quickly in response, avoiding open battle with Louis in Aquitaine and stabilising the Norman border, pillaging the Vexin and then striking south into Anjou against Geoffrey, capturing one of his main castles (Montsoreau).[51] Louis fell ill and withdrew from the campaign, and Geoffrey was forced to come to terms with Henry.[49]

Taking the English throne

In response to Stephen's siege, Henry returned to England again at the start of 1153, braving winter storms.[52] Bringing only a small army of mercenaries, probably paid for with borrowed money, Henry was supported in the north and east of England by the forces of Ranulf of Chester and Hugh Bigod, and had hopes of a military victory.[53] A delegation of senior English clergy met with Henry and his advisers at Stockbridge, Hampshire, shortly before Easter in April.[54] Details of their discussions are unclear, but it appears that the churchmen emphasised that while they supported Stephen as king, they sought a negotiated peace; Henry reaffirmed that he would avoid the English cathedrals and would not expect the bishops to attend his court.[55]

To draw Stephen's forces away from Wallingford, Henry besieged Stephen's castle at Malmesbury, and the King responded by marching west with an army to relieve it.[56] Henry successfully evaded Stephen's larger army along the River Avon, preventing Stephen from forcing a decisive battle.[57] In the face of the increasingly wintry weather, the two men agreed to a temporary truce, leaving Henry to travel north through the Midlands, where the powerful Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, announced his support for the cause.[57] Henry was then free to turn his forces south against the besiegers at Wallingford.[58] Despite only modest military successes, he and his allies now controlled the south-west, the Midlands and much of the north of England.[59] Meanwhile, Henry was attempting to act the part of a legitimate king, witnessing marriages and settlements and holding court in a regal fashion.[60]

Over the next summer, Stephen massed troops to renew the siege of Wallingford Castle in a final attempt to take the stronghold.[61] The fall of Wallingford appeared imminent and Henry marched south to relieve the siege, arriving with a small army and placing Stephen's besieging forces under siege themselves.[62] Upon news of this, Stephen returned with a large army, and the two sides confronted each other across the River Thames at Wallingford in July.[62] By this point in the war, the barons on both sides were eager to avoid an open battle,[63] so members of the clergy brokered a truce, to the annoyance of both Henry and Stephen.[63] Henry and Stephen took the opportunity to speak together privately about a potential end to the war; conveniently for Henry, Stephen's son Eustace fell ill and died shortly afterwards.[64] This removed the most obvious other claimant to the throne, as while Stephen had another son, William, he was only a second son and appeared unenthusiastic about making a plausible claim on the throne.[65] Fighting continued after Wallingford, but in a rather half-hearted fashion, while the English Church attempted to broker a permanent peace between the two sides.[66]

In November the two leaders ratified the terms of a permanent peace.[67] Stephen announced the Treaty of Winchester in Winchester Cathedral: he recognised Henry as his adopted son and successor, in return for Henry paying homage to him; Stephen promised to listen to Henry's advice, but retained all his royal powers; Stephen's son William would pay homage to Henry and renounce his claim to the throne, in exchange for promises of the security of his lands; key royal castles would be held on Henry's behalf by guarantors whilst Stephen would have access to Henry's castles; and the numerous foreign mercenaries would be demobilised and sent home.[68] Henry and Stephen sealed the treaty with a kiss of peace in the cathedral.[69] The peace remained precarious, and Stephen's son William remained a possible future rival to Henry.[70] Rumours of a plot to kill Henry were circulating and, possibly as a consequence, Henry decided to return to Normandy for a period.[70][nb 8] Stephen fell ill with a stomach disorder and died on 25 October 1154, allowing Henry to inherit the throne rather sooner than had been expected.[72]

Reconstruction of royal government

On landing in England on 8 December 1154, Henry quickly took oaths of loyalty from some of the barons and was then crowned alongside Eleanor at Westminster Abbey on 19 December.[73] The royal court was gathered in April 1155, where the barons swore fealty to the King and his sons.[73] Several potential rivals still existed, including Stephen's son William and Henry's brothers Geoffrey and William, but they all died in the next few years, leaving Henry's position remarkably secure.[74] Nonetheless, Henry inherited a difficult situation in England, as the kingdom had suffered extensively during the civil war.[nb 9] In many parts of the country the fighting had caused serious devastation, although some other areas remained largely unaffected.[76] Numerous "adulterine", or unauthorised, castles had been built as bases for local lords.[77] The royal forest law had collapsed in large parts of the country.[78] The King's income had declined seriously and royal control over the coin mints remained limited.[79]

Henry presented himself as the legitimate heir to Henry I and commenced rebuilding the kingdom in his image.[80] Although Stephen had tried to continue Henry I's method of government during his reign, the younger Henry's new government characterised those nineteen years as a chaotic and troubled period, with all these problems resulting from Stephen's usurpation of the throne.[81] Henry was also careful to show that, unlike his mother the Empress, he would listen to the advice and counsel of others.[82] Various measures were immediately carried out although, since Henry spent six and a half years out of the first eight years of his reign in France, much work had to be done at a distance.[83] The process of demolishing the unauthorised castles from the war continued.[84][nb 10] Efforts were made to restore the system of royal justice and the royal finances. Henry also invested heavily in the construction and renovation of prestigious new royal buildings.[85]

The King of Scotland and local Welsh rulers had taken advantage of the long civil war in England to seize disputed lands; Henry set about reversing this trend.[86] In 1157 pressure from Henry resulted in the young King Malcolm of Scotland returning the lands in the north of England he had taken during the war; Henry promptly began to refortify the northern frontier.[87] Restoring Anglo-Norman supremacy in Wales proved harder, and Henry had to fight two campaigns in north and south Wales in 1157 and 1158 before the Welsh princes Owain Gwynedd and Rhys ap Gruffydd submitted to his rule, agreeing to the pre-civil war borders.[88]

Campaigns in Brittany, Toulouse and the Vexin

Henry had a problematic relationship with Louis VII of France throughout the 1150s. The two men had already clashed over Henry's succession to Normandy and the remarriage of Eleanor, and the relationship was not repaired. Louis invariably attempted to take the moral high ground in respect to Henry, capitalising on his reputation as a crusader and circulating rumours about his rival's behaviour and character.[90] Henry had greater resources than Louis, particularly after taking England, and Louis was far less dynamic in resisting Angevin power than he had been earlier in his reign.[91] The disputes between the two drew in other powers across the region, including Thierry, Count of Flanders, who signed a military alliance with Henry, albeit with a clause that prevented the count from being forced to fight against Louis, his feudal lord.[92] Further south, Theobald V, Count of Blois, an enemy of Louis, became another early ally of Henry.[93] The resulting military tensions and the frequent face-to-face meetings to attempt to resolve them has led historian Jean Dunbabin to liken the situation to the period of the Cold War in Europe in the 20th century.[94]

On his return to the continent from England, Henry sought to secure his French lands and quash any potential rebellion.[95] As a result, in 1154 Henry and Louis agreed a peace treaty, under which Henry bought back the Vernon and the Neuf-Marché from Louis.[30] The treaty appeared shaky, and tensions remained—in particular, Henry had not given homage to Louis for his French possessions.[96][nb 11] They met at Paris and Mont-Saint-Michel in 1158, agreeing to betroth Henry's eldest living son, the Young Henry, to Louis's daughter Margaret.[98] The marriage deal would have involved Louis granting the disputed territory of the Vexin to Margaret on her marriage to the Young Henry: while this would ultimately give Henry the lands that he claimed, it also cunningly implied that the Vexin was Louis's to give away in the first place, in itself a political concession.[99] For a short while, a permanent peace between Henry and Louis looked plausible.[98]

Meanwhile, Henry turned his attention to the Duchy of Brittany, which neighboured his lands and was traditionally largely independent from the rest of France, with its own language and culture.[100] The Breton dukes held little power across most of the duchy, which was mostly controlled by local lords.[101] In 1148, Duke Conan III died and civil war broke out.[102] Henry claimed to be the overlord of Brittany, on the basis that the duchy had owed loyalty to Henry I, and saw controlling the duchy both as a way of securing his other French territories and as a potential inheritance for one of his sons.[103][nb 12] Initially Henry's strategy was to rule indirectly through proxies, and accordingly Henry supported Conan IV's claims over most of the duchy, partly because Conan had strong English ties and could be easily influenced.[105] Conan's uncle, Hoël, continued to control the county of Nantes in the east until he was deposed in 1156 by Henry's brother, Geoffrey, possibly with Henry's support.[106] When Geoffrey died in 1158, Conan attempted to reclaim Nantes but was opposed by Henry who annexed it for himself.[107] Louis took no action to intervene as Henry steadily increased his power in Brittany.[108]

Henry hoped to take a similar approach to regaining control of Toulouse in southern France.[108] Toulouse, while technically part of the Duchy of Aquitaine, had become increasingly independent and was now ruled by Count Raymond V, who had only a weak claim to the lands.[109] Encouraged by Eleanor, Henry first allied himself with Raymond's enemy Raymond Berenguer of Barcelona and then in 1159 threatened to invade himself to depose the Count of Tolouse.[109] Louis married his sister Constance to the Count in an attempt to secure his southern frontiers; nonetheless, when Henry and Louis discussed the matter of Toulouse, Henry left believing that he had the French King's support for military intervention.[110] Henry invaded Toulouse, only to find Louis visiting Raymond in the city.[111] Henry was not prepared to directly attack Louis, who was still his feudal lord, and withdrew, settling himself with ravaging the surrounding county, seizing castles and taking the province of Quercy.[111] The episode proved to be a long-running point of dispute between the two kings and the chronicler William of Newburgh called the ensuing conflict with Toulouse a "forty years' war".[112]

In the aftermath of the Toulouse episode, Louis made an attempt to repair relations with Henry through an 1160 peace treaty: this promised Henry the lands and the rights of his grandfather, Henry I; it reaffirmed the betrothal of Young Henry and Margaret and the Vexin deal; and it involved Young Henry giving homage to Louis, a way of reinforcing the young boy's position as heir and Louis's position as king.[113] Almost immediately after the peace conference, Louis shifted his position considerably. His wife Constance died and he married Adèle, the sister of the Counts of Blois and Champagne.[114] Louis also betrothed daughters by Eleanor to Adèle's brothers Theobald V, Count of Blois, and Henry I, Count of Champagne.[115] This represented an aggressive containment strategy towards Henry rather than the agreed rapprochement, and caused Theobald to abandon his alliance with Henry.[115] Henry reacted angrily; the King had custody of both Young Henry and Margaret, and in November he bullied several papal legates into marrying them—despite the children being only five and three years old respectively—and promptly seized the Vexin.[116][nb 13] Now it was Louis's turn to be furious, as the move clearly broke the spirit of the 1160 treaty.[120]

Military tensions between the two leaders immediately increased. Theobald mobilised his forces along the border with Touraine; Henry responded by attacking Chaumont in Blois in a surprise attack; he successfully took Theobald's castle in a notable siege.[115] At the start of 1161 war seemed likely to spread across the region, until a fresh peace was negotiated at Fréteval that autumn, followed by a second peace treaty in 1162, overseen by Pope Alexander III.[121] Despite this temporary halt in hostilities, Henry's seizure of the Vexin proved to be a second long-running dispute between him and the kings of France.[122]

Government, family and household

Empire and nature of government

Henry controlled more of France than any ruler since the Carolingians; these lands, combined with his possessions in England, Wales, Scotland and much of Ireland, produced a vast domain often referred to by historians as the Angevin Empire.[123] The empire lacked a coherent structure or central control; instead, it consisted of a loose, flexible network of family connections and lands.[124] Different local customs applied within each of Henry's different territories, although common principles underpinned some of these local variations.[125][nb 14] Henry travelled constantly across the empire, producing what the historian John Jolliffe describes as a "government of the roads and roadsides".[127][nb 15] His travels coincided with regional governmental reforms and other local administrative business, although messengers connected him to his possession wherever he went.[129] In his absence the lands were ruled by seneschals and justiciars, and beneath them local officials in each of the regions carried on with the business of government.[130] Nonetheless, many of the functions of government centred on Henry himself and he was often surrounded by petitioners requesting decisions or favours.[131][nb 16]

From time to time, Henry's royal court became a magnum concilium, a great council; these were sometimes used to take major decisions but the term was loosely applied whenever many barons and bishops attended the king.[133] A great council was supposed to advise the King and give assent to royal decisions, although it is unclear how much freedom they actually enjoyed to oppose Henry's intentions.[134] Henry also appears to have consulted with his court when making legislation; the extent to which he then took their views into account is unclear.[135] As a powerful ruler, Henry was able to provide either valuable patronage or impose devastating harm on his subjects.[136] Using his powers of patronage, he was very effective at finding and keeping competent officials, including within the Church, in the 12th century a key part of royal administration.[137] Indeed, royal patronage within the Church provided an effective route to advancement under Henry and most of his preferred clerics eventually became bishops and archbishops.[138][nb 17] Henry could also show his ira et malevolentia—"anger and ill-will"—a term that described his ability to punish or financially destroy particular barons or clergy.[140]

In England, Henry initially relied on his father's former advisers whom he brought with him from Normandy, and on some of Henry I's remaining officials, reinforced with some of Stephen's senior nobility who made their peace with Henry in 1153.[141] During his reign Henry, like his grandfather, increasingly promoted "new men", minor nobles without independent wealth and lands, to positions of authority in England.[142] By the 1180s this new class of royal administrators was predominant in England, supported by various illegitimate members of Henry's family.[143] In Normandy, the links between the two halves of the Anglo-Norman nobility had weakened during the first half of the 12th century, and continued to do so under Henry.[144] Henry drew his close advisers from the ranks of the Norman bishops and, as in England, recruited many "new men" as Norman administrators: few of the larger landowners in Normandy benefited from the King's patronage.[145] He frequently intervened with the Norman nobility through arranged marriages or the treatment of inheritances, either using his authority as duke or his influence as king of England over their lands there: Henry's rule was a harsh one. Across the rest of France, local administration was less developed: Anjou was governed through a combination of officials called prévôts and seneschals based along the Loire and in western Touraine, but Henry had few officials elsewhere in the region.[146] In Aquitaine, ducal authority remained very limited, despite increasing significantly during Henry's reign, largely due to Richard's efforts in the late 1170s.[147]

Court and family

Henry's wealth allowed him to maintain what was probably the largest curia regis, or royal court, in Europe.[148] His court attracted huge attention from contemporary chroniclers, and typically comprised several major nobles and bishops, along with knights, domestic servants, prostitutes, clerks, horses and hunting dogs.[149][nb 18] Within the court were his officials, ministeriales, his friends, amici, and the familiares regis, the King's informal inner circle of confidants and trusted servants.[151] Henry's familiares were particularly important to the operation of his household and government, driving government initiatives and filling the gaps between the official structures and the King.[152]

Henry tried to maintain a sophisticated household that combined hunting and drinking with cosmopolitan literary discussion and courtly values.[153][nb 19] Nonetheless, Henry's passion was for hunting, for which the court became famous.[155] Henry had several preferred royal hunting lodges and apartments across his lands, and invested heavily in his royal castles, both for their practical utility as fortresses, and as symbols of royal power and prestige.[156] The court was relatively formal in its style and language, possibly because Henry was attempting to compensate for his own sudden rise to power and relatively humble origins as the son of a count.[157] He opposed the holding of tournaments, probably because of the security risk that such gatherings of armed knights posed in peacetime.[158]

The Angevin Empire and court was, as historian John Gillingham describes it, "a family firm".[159] His mother, Matilda, played an important role in his early life and exercised influence for many years later.[160] Henry's relationship with his wife Eleanor was complex: Henry trusted Eleanor to manage England for several years after 1154, and was later content for her to govern Aquitaine; indeed, Eleanor was believed to have influence over Henry during much of their marriage.[161] Ultimately, their relationship disintegrated and chroniclers and historians have speculated on what ultimately caused Eleanor to abandon Henry to support her older sons in the Great Revolt of 1173–74.[162] Probable explanations include Henry's persistent interference in Aquitaine, his recognition of Raymond of Toulouse in 1173, or his harsh temper.[163] He had several long-term mistresses, including Annabel de Balliol and Rosamund Clifford.[164][nb 20]

Henry had eight legitimate children by Eleanor, five sons—William, the Young Henry, Richard, Geoffrey and John, and three daughters, Matilda, Eleanor and Joan.[nb 21] He also had several illegitimate children; amongst the most prominent of these were Geoffrey (later Archbishop of York) and William (later Earl of Salisbury).[166] Henry was expected to provide for the future of his legitimate children, either through granting lands to his sons or marrying his daughters well.[167] His family was divided by rivalries and violent hostilities, more so than many other royal families of the day, in particular the relatively cohesive French Capetians.[168] Various suggestions have been put forward to explain Henry's family's bitter disputes, from their inherited family genetics to the failure of Henry and Eleanor's parenting.[169] Other theories focus on the personalities of Henry and his children.[170] Historians such as Matthew Strickland have argued that Henry made sensible attempts to manage the tensions within his family, and that had he died younger, the succession might have proven much smoother.[171]

Law

Henry's reign saw significant legal changes, particularly in England and Normandy.[172][nb 22] By the middle of the 12th century, England had many different ecclesiastical and civil law courts, with overlapping jurisdictions resulting from the interaction of diverse legal traditions. Henry greatly expanded the role of royal justice in England, producing a more coherent legal system, summarised at the end of his reign in the treatise of Glanvill, an early legal handbook.[174] Despite these reforms it is uncertain if Henry had a grand vision for his new legal system and the reforms seem to have proceeded in a steady, pragmatic fashion.[175] Indeed, in most cases he was probably not personally responsible for creating the new processes, but he was greatly interested in the law, seeing the delivery of justice as one of the key tasks for a king and carefully appointing good administrators to conduct the reforms.[176][nb 23]

In the aftermath of the disorders of Stephen's reign in England there were many legal cases concerning land to be resolved: many religious houses had lost land during the conflict, while in other cases owners and heirs had been dispossessed of their property by local barons, which in some cases had since been sold or given to new owners.[178] Henry relied on traditional, local courts—such as the shire courts, hundred courts and in particular seignorial courts—to deal with most of these cases, hearing only a few personally.[179] This process was far from perfect and in many cases claimants were unable to pursue their cases effectively.[180] While interested in the law, during the first years of his reign Henry was preoccupied with other political issues and even finding the King for a hearing could mean travelling across the Channel and locating his peripatetic court.[181] Nonetheless, he was prepared to take action to improve the existing procedures, intervening in cases which he felt had been mishandled, and creating legislation to improve both ecclesiastical and civil court processes.[182] Meanwhile, in neighbouring Normandy, Henry delivered justice through the courts run by his officials across the duchy and occasionally these cases made their way to the King himself.[183] He also operated an exchequer court at Caen that heard cases relating to royal revenues and maintained king's justices who travelled across the duchy.[184] Between 1159 and 1163, Henry spent time in Normandy conducting reforms of royal and church courts and some measures later introduced in England are recorded as existing in Normandy as early as 1159.[185]

In 1163 Henry returned to England, intent on reforming the role of the royal courts.[186] He cracked down on crime, seizing the belongings of thieves and fugitives, and travelling justices were dispatched to the north and the Midlands.[187] After 1166, Henry's exchequer court in Westminster, which had previously only heard cases connected with royal revenues, began to take wider civil cases on behalf of the King.[188] The reforms continued and Henry created the General Eyre, probably in 1176, which involved dispatching a group of royal justices to visit all the counties in England over a given period of time, with authority to cover both civil and criminal cases.[189] Local juries were used occasionally in previous reigns, but Henry made much wider use of them.[190] Juries were introduced in petty assizes from around 1176, where they were used to establish the answers to particular pre-established questions, and in grand assizes from 1179, where they were used to determine the guilt of a defendant.[190] Other methods of trial continued, including trial by combat and trial by ordeal.[191] After the Assize of Clarendon in 1166, royal justice was extended into new areas through the use of new forms of assizes, in particular novel disseisin, mort d'ancestor and dower unde nichil habet, which dealt with the wrongful dispossession of land, inheritance rights and the rights of widows respectively.[192] In making these reforms Henry both challenged the traditional rights of barons in dispensing justice and reinforced key feudal principles, but over time they greatly increased royal power in England.[193][nb 24]

Relations with the Church

Henry's relationship with the Church varied considerably across his lands and over time: as with other aspects of his rule, there was no attempt to form a common ecclesiastical policy.[194] Insofar as he had a policy, it was to generally resist papal influence, increasing his own local authority.[195] The 12th century saw a reforming movement within the Church, advocating greater autonomy from royal authority for the clergy and more influence for the papacy.[196] This trend had already caused tensions in England, for example when King Stephen forced Theobald of Bec, the Archbishop of Canterbury, into exile in 1152.[197] There were also long-running concerns over the legal treatment of members of the clergy.[198]

By contrast with the tensions in England, in Normandy Henry had occasional disagreements with the Church but generally enjoyed very good relations with the Norman bishops.[199] In Brittany, he had the support of the local church hierarchy and rarely intervened in clerical matters, except occasionally to cause difficulties for his rival Louis of France.[200] Further south, the power of the dukes of Aquitaine over the local church was much less than in the north, and Henry's efforts to extend his influence over local appointments created tensions.[201] During the disputed papal election of 1159, Henry, like Louis, supported Alexander III over his rival Victor IV.[117]

Henry was not an especially pious king by medieval standards.[202] In England, he provided steady patronage to the monastic houses, but established few new monasteries and was relatively conservative in determining which he did support, favouring those with established links to his family, such as Reading Abbey.[203] In this regard Henry's religious tastes appear to have been influenced by his mother, and before his ascension several religious charters were issued in their joint names.[31] Henry also founded religious hospitals in England and France.[204] After the death of Becket, he built and endowed various monasteries in France, primarily to improve his popular image.[205] Since travel by sea during the period was dangerous, he would also take full confession before setting sail and use auguries to determine the best time to travel.[206] Henry's movements may also have been planned to take advantage of saints' days and other fortuitous occasions.[207]

Economy and finance

Henry restored many of the old financial institutions of his grandfather Henry I and undertook further, long-lasting reforms of the way that the English currency was managed; one result was a long-term increase in the supply of money within the economy, leading to a growth both in trade and inflation.[208] Medieval rulers such as Henry enjoyed various sources of income during the 12th century. Some of their income came from their private estates, called demesne; other income came from imposing legal fines and arbitrary amercements, and from taxes, which at this time were raised only intermittently.[209] Kings could also raise funds by borrowing; Henry did this far more than earlier English rulers, initially through moneylenders in Rouen, turning later in his reign to Jewish and Flemish lenders.[210] Ready cash was increasingly important to rulers during the 12th century to enable the use of mercenary forces and the construction of stone castles, both vital to successful military campaigns.[211]

Henry inherited a difficult situation in England in 1154. Henry I had established a system of royal finances that depended upon three key institutions: a central royal treasury in London, supported by treasuries in key castles; the exchequer that accounted for payments to the treasuries; and a team of royal officials called "the chamber" that followed the King's travels, spending money as necessary and collecting revenues along the way.[212] The long civil war had caused considerable disruption to this system and some figures suggest that royal income fell by 46% between 1129–30 and 1155–56.[213] A new coin, called the Awbridge silver penny, was issued in 1153 in an attempt to stabilise the English currency after the war.[214] Less is known about how financial affairs were managed in Henry's continental possessions, but a very similar system operated in Normandy, and a comparable system probably operated in both Anjou and Aquitaine.[215]

On taking power Henry gave a high priority to the restoration of royal finances in England, reviving Henry I's financial processes and attempting to improve the quality of the royal accounting.[216] Revenue from the demesne formed the bulk of Henry's income in England, although taxes were used heavily in the first 11 years of his reign.[217] Aided by the capable Richard FitzNeal, he reformed the currency in 1158, putting his name on English coins for the first time and heavily reducing the number of moneyers licensed to produce coins.[218][nb 25] These measures were successful in improving his income, but on his return to England in the 1160s Henry took further steps.[222] New taxes were introduced and the existing accounts re-audited, and the reforms of the legal system brought in new streams of money from fines and amercements.[223] A wholesale reform of the coinage occurred in 1180, with royal officials taking direct control of the mints and passing the profits directly to the treasury.[224] A new penny, called the Short Cross, was introduced, and the number of mints reduced substantially to ten across the country.[225] Driven by the reforms, the royal revenues increased significantly; during the first part of the reign, Henry's average exchequer income was only around £18,000; after 1166, the average was around £22,000.[226] One economic effect of these changes was a substantial increase in the amount of money in circulation in England and, post-1180, a significant, long-term increase in both inflation and trade.[227]

Later reign (1162–1175)

Developments in France

Long-running tensions between Henry and Louis VII continued during the 1160s, the French king slowly becoming more vigorous in opposing Henry's increasing power in Europe.[108] In 1160 Louis strengthened his alliances in central France with the Count of Champagne and Odo II, Duke of Burgundy. Three years later the new Count of Flanders, Philip, concerned about Henry's growing power, openly allied himself with the French King.[228] Louis's wife Adèle gave birth to a male heir, Philip Augustus, in 1165, and Louis was more confident of his own position than for many years previously.[229] As a result, relations between Henry and Louis deteriorated again in the mid-1160s.[230]

Meanwhile, Henry had begun to alter his policy of indirect rule in Brittany and started to exert more direct control.[231] In 1164 he intervened to seize lands along the border of Brittany and Normandy, and in 1166 invaded Brittany to punish the local barons.[232] Henry then forced Conan to abdicate as duke and to give Brittany to his daughter Constance; Constance was handed over and betrothed to Henry's son Geoffrey.[232] This arrangement was quite unusual in terms of medieval law, as Conan might have had sons who could have legitimately inherited the duchy.[233][nb 26] Elsewhere in France, Henry attempted to seize the Auvergne, much to the anger of the French King.[234] Further south Henry continued to apply pressure on Raymond of Toulouse: the King campaigned there personally in 1161, sent the Archbishop of Bordeaux against Raymond in 1164 and encouraged Alfonso II of Aragon in his attacks.[235] In 1165 Raymond divorced Louis's sister and attempted to ally himself with Henry instead.[234]

These growing tensions between Henry and Louis finally spilled over into open war in 1167, triggered by a trivial argument over how money destined for the Crusader states of the Levant should be collected.[234] Louis allied himself with the Welsh, Scots and Bretons, and attacked Normandy.[236] Henry responded by attacking Chaumont-sur-Epte, where Louis kept his main military arsenal, burning the town to the ground and forcing Louis to abandon his allies and make a private truce.[237] Henry was then free to move against the rebel barons in Brittany, where feelings about his seizure of the duchy were still running high.[238]

As the decade progressed, Henry increasingly wanted to resolve the question of the inheritance. He decided that he would divide up his empire after his death, with Young Henry receiving England and Normandy, Richard being given the Duchy of Aquitaine, and Geoffrey acquiring Brittany.[239] This would require the consent of Louis, and accordingly the kings held fresh peace talks in 1169 at Montmirail.[240] The talks were wide-ranging, culminating with Henry's sons giving homage to Louis for their future inheritances in France. Also at this time, Richard was betrothed to Louis's young daughter Alys.[241] Alys (also spelled "Alice") came to England and later became the mistress of King Henry, which explains why she was not married to Richard as originally intended. After Henry’s death, Alys returned to France and in 1195 married William Talvas, Count of Ponthieu.[242]

If the agreements at Montmirail had been followed up, the acts of homage could potentially have confirmed Louis's position as king, while undermining the legitimacy of any rebellious barons within Henry's territories and the potential for an alliance between them and Louis.[243] In practice, Louis perceived himself to have gained a temporary advantage, and immediately after the conference he began to encourage tensions between Henry's sons.[244] Meanwhile, Henry's position in the south of France continued to improve, and by 1173 he had agreed to an alliance with Humbert III, Count of Savoy, which betrothed Henry's son John and Humbert's daughter Alicia.[235][nb 27] Henry's daughter Eleanor was married to Alfonso VIII of Castile in 1170, enlisting an additional ally in the south.[235] In February 1173, Raymond finally gave in and publicly gave homage for Toulouse to Henry and his heirs.[235]

Thomas Becket controversy

One of the major international events surrounding Henry during the 1160s was the Becket controversy. When the Archbishop of Canterbury, Theobald of Bec, died in 1161 Henry saw an opportunity to reassert his rights over the church in England.[245] Henry appointed Thomas Becket, his English Chancellor, as archbishop in 1162, probably believing that Becket, in addition to being an old friend, would be politically weakened within the Church because of his former role as Chancellor, and would therefore have to rely on Henry's support.[246] Both Henry's mother and wife appear to have had doubts about the appointment, but he continued regardless.[247] His plan did not have the desired result, as Becket promptly changed his lifestyle, abandoned his links to the King and portrayed himself as a staunch protector of church rights.[248]

Henry and Becket quickly disagreed over several issues, including Becket's attempts to regain control of lands belonging to the archbishopric and his views on Henry's taxation policies.[249] The main source of conflict concerned the treatment of clergy who committed secular crimes: Henry argued that the legal custom in England allowed the King to enforce justice over these clerics, while Becket maintained that only church courts could try the cases. The matter came to a head in January 1164, when Henry forced through agreement to the Constitutions of Clarendon; under tremendous pressure, Becket temporarily agreed but changed his position shortly afterwards.[250] The legal argument was complex at the time and remains contentious.[251][nb 28]

The argument between Henry and Becket became both increasingly personal and international in nature. Henry was stubborn and bore grudges, while Becket was vain, ambitious and overly political: neither man was willing to back down.[253] Both sought the support of Alexander III and other international leaders, arguing their positions in various forums across Europe.[254] The situation worsened in 1164 when Becket fled to France to seek sanctuary with Louis VII.[255] Henry harassed Becket's associates in England, and Becket excommunicated religious and secular officials who sided with the King.[256] The pope supported Becket's case in principle but needed Henry's support in dealing with Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor, so he repeatedly sought a negotiated solution; the Norman church also intervened to try to assist Henry in finding a solution.[257]

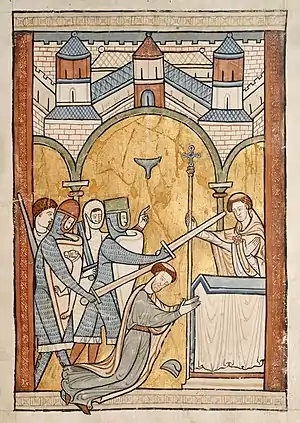

By 1169, Henry had decided to crown his son Young Henry as King of England. This required the acquiescence of the Archbishop of Canterbury, traditionally the churchman with the right to conduct the ceremony. Furthermore, the whole Becket matter was an increasing international embarrassment to Henry. He began to take a more conciliatory tone with Becket but, when this failed, had Young Henry crowned anyway by the Archbishop of York. The pope authorized Becket to lay an interdict on England, forcing Henry back to negotiations; they finally came to terms in July 1170, and Becket returned to England in early December. Just when the dispute seemed resolved, Becket excommunicated another three supporters of Henry, who was furious and infamously announced "What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and promoted in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk!"[258]

In response, four knights made their way secretly to Canterbury, apparently with the intent of confronting and if necessary arresting Becket for breaking his agreement with Henry.[259] The Archbishop refused to be arrested inside the sanctuary of a church, so the knights hacked him to death on 29 December 1170.[260] This event, particularly in front of an altar, horrified Christian Europe. Although Becket had not been popular while he was alive, in death he was declared a martyr by the local monks.[261] Louis seized on the case, and, despite efforts by the Norman church to prevent the French church from taking action, a new interdict was announced on Henry's possessions.[262] Henry was focused on dealing with Ireland and took no action to arrest Becket's killers, arguing that he was unable to do so.[263] International pressure on Henry grew, and in May 1172 he negotiated a settlement with the papacy in which the King swore to go on crusade as well as effectively overturning the Constitutions of Clarendon.[264] In the coming years, although Henry never actually went on crusade, he exploited the growing "cult of Becket" for his own ends.[265]

Arrival in Ireland

In the mid-12th century Ireland was ruled by local kings, although their authority was more limited than their counterparts in the rest of western Europe.[266] Mainstream Europeans regarded the Irish as relatively barbarous and backward.[267] In the 1160s the King of Leinster, Diarmait Mac Murchada, was deposed by the High King of Ireland, Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair. Diarmait turned to Henry for assistance in 1167, and the English King agreed to allow Diarmait to recruit mercenaries within his empire.[268] Diarmait put together a force of Anglo-Norman and Flemish mercenaries drawn from the Welsh Marches, including Richard de Clare, Earl of Pembroke.[269] With his new supporters, he reclaimed Leinster but died shortly afterwards in 1171; de Clare then claimed Leinster for himself. The situation in Ireland was tense and the Anglo-Normans heavily outnumbered.[270]

Henry took this opportunity to intervene personally in Ireland. He took a large army into south Wales, forcing the rebels who had held the area since 1165 into submission before sailing from Pembroke, Pembrokeshire, and landing in Ireland in October 1171.[271] Some of the Irish lords appealed to Henry to protect them from the Anglo-Norman invaders, while de Clare offered to submit to him if allowed to retain his new possessions.[270] Henry's timing was influenced by several factors, including encouragement from Pope Alexander, who saw the opportunity to establish papal authority over the Irish church.[272] The critical factor though appears to have been Henry's concern that his nobles in the Welsh Marches would acquire independent territories of their own in Ireland, beyond the reach of his authority.[273] Henry's intervention was successful, and both the Irish and Anglo-Normans in the south and east of Ireland accepted his rule.[274]

Henry undertook a wave of castle-building during his visit in 1171 to protect his new territories—the Anglo-Normans had superior military technologies to the Irish, and castles gave them a significant advantage.[275] Henry hoped for a longer-term political solution, similar to his approach in Wales and Scotland, and in 1175 he agreed to the Treaty of Windsor, under which Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair would be recognised as the High King of Ireland, giving homage to Henry and maintaining stability on the ground on his behalf.[276] This policy proved unsuccessful, as Ua Conchobair was unable to exert sufficient influence and force in areas such as Munster: Henry instead intervened more directly, establishing a system of local fiefs of his own through a conference held in Oxford in 1177.[277]

Great Revolt (1173–1174)

In 1173 Henry faced the Great Revolt, an uprising by his eldest sons and rebellious barons, supported by France, Scotland and Flanders. Several grievances underpinned the revolt. Young Henry was unhappy that, despite the title of king, in practice he made no real decisions and his father kept him chronically short of money.[278] He had also been very attached to Thomas Becket, his former tutor, and may have held his father responsible for Becket's death.[246] Geoffrey faced similar difficulties; Duke Conan of Brittany had died in 1171, but Geoffrey and Constance were still unmarried, leaving Geoffrey in limbo without his own lands.[279] Richard was encouraged to join the revolt as well by Eleanor, whose relationship with Henry had disintegrated.[280] Meanwhile, local barons unhappy with Henry's rule saw opportunities to recover traditional powers and influence by allying themselves with his sons.[281]

The final straw was Henry's decision to give his youngest son John three major castles belonging to Young Henry, who first protested and then fled to Paris, followed by his brothers Richard and Geoffrey; Eleanor attempted to join them but was captured by Henry's forces in November.[282] Louis supported Young Henry and war became imminent.[283] Young Henry wrote to the pope, complaining about his father's behaviour, and began to acquire allies, including King William of Scotland and the Counts of Boulogne, Flanders and Blois—all of whom were promised lands if Young Henry won.[284] Major baronial revolts broke out in England, Brittany, Maine, Poitou and Angoulême.[285] In Normandy some of the border barons rose up and, although the majority of the duchy remained openly loyal, there appears to have been a wider undercurrent of discontent.[286][nb 29] Only Anjou proved relatively secure.[285] Despite the size and scope of the crisis, Henry had several advantages, including his control of many powerful royal castles in strategic areas, control of most of the English ports throughout the war, and his continuing popularity within the towns across his empire.[288]

In May 1173 Louis and Young Henry probed the defences of the Vexin, the main route to the Norman capital, Rouen; armies invaded from Flanders and Blois, attempting a pincer movement, while rebels from Brittany invaded from the west.[289] Henry secretly travelled back to England to order an offensive on the rebels, and on his return counter-attacked Louis's army, massacring many of them and pushing them back across the border.[290] An army was dispatched to drive back the Brittany rebels, whom Henry then pursued, surprised and captured.[291] Henry offered to negotiate with his sons, but these discussions at Gisors soon broke down.[291] Meanwhile, the fighting in England proved evenly balanced until a royal army defeated a superior force of rebel and Flemish reinforcements in September in the battle of Fornham near Fornham All Saints in East Anglia.[292] Henry took advantage of this respite to crush the rebel strongholds in Touraine, securing the strategically important route through his empire.[293] In January 1174 the forces of Young Henry and Louis attacked again, threatening to push through into central Normandy.[293] The attack failed and the fighting paused while the winter weather set in.[293]

In early 1174, Henry's enemies appeared to have tried to lure him back into England, allowing them to attack Normandy in his absence.[293] As part of this plan, William of Scotland attacked the south of England, supported by the northern English rebels; additional Scottish forces were sent into the Midlands, where the rebel barons were making good progress.[294] Henry refused the bait and instead focused on crushing opposition in south-west France. William's campaign began to falter as the Scots failed to take the key northern royal castles, in part due to the efforts of Henry's illegitimate son, Geoffrey.[295] In an effort to reinvigorate the plan, Philip, the Count of Flanders, announced his intention to invade England and sent an advance force into East Anglia.[296] The prospective Flemish invasion forced Henry to return to England in early July.[297] Louis and Philip could now push overland into eastern Normandy and reached Rouen.[297] Henry travelled to Becket's tomb in Canterbury, where he announced that the rebellion was a divine punishment on him, and took appropriate penance; this made a major difference in restoring his royal authority at a critical moment in the conflict.[298] Word then reached Henry that King William had been defeated and captured by local forces at Alnwick, crushing the rebel cause in the north.[297] The remaining English rebel strongholds collapsed and in August Henry returned to Normandy.[299] Louis had not yet been able to take Rouen, and Henry's forces fell upon the French army just before the final French assault on the city began; pushed back into France, Louis requested peace talks, bringing an end to the conflict.[299]

Final years (1175–1189)

Aftermath of the Great Revolt

In the aftermath of the Great Revolt, Henry held negotiations at Montlouis, offering a lenient peace on the basis of the pre-war status quo.[300] Henry and Young Henry swore not to take revenge on each other's followers; Young Henry agreed to the transfer of the disputed castles to John, but in exchange the elder Henry agreed to give the younger Henry two castles in Normandy and 15,000 Angevin pounds; Richard and Geoffrey were granted half the revenues from Aquitaine and Brittany respectively.[301][nb 30] Eleanor was kept under effective house arrest until the 1180s.[303] The rebel barons were kept imprisoned for a short time and in some cases fined, then restored to their lands.[304] The rebel castles in England and Aquitaine were destroyed.[305] Henry was less generous to William of Scotland, who was not released until he had agreed to the Treaty of Falaise in December 1174, under which he publicly gave homage to Henry and surrendered five key Scottish castles to Henry's men.[306] Philip of Flanders declared his neutrality towards Henry, in return for which the King agreed to provide him with regular financial support.[92]

Henry now appeared to his contemporaries to be stronger than ever, and he was courted as an ally by many European leaders and asked to arbitrate over international disputes in Spain and Germany.[307] He was nonetheless busy resolving some of the weaknesses that he believed had exacerbated the revolt. Henry set about extending royal justice in England to reassert his authority and spent time in Normandy shoring up support amongst the barons.[308] The King also made use of the growing Becket cult to increase his own prestige, using the power of the saint to explain his victory in 1174, especially his success in capturing William.[309]

The 1174 peace did not deal with the long-running tensions between Henry and Louis, and these resurfaced during the late 1170s.[310] The two kings now began to compete for control of Berry, a prosperous region of value to both kings.[310] Henry had some rights to western Berry, but in 1176 announced an extraordinary claim that he had agreed in 1169 to give Richard's fiancée Alys the whole province as part of the marriage settlement.[311] If Louis accepted this, it would have implied that the Berry was Henry's to give away in the first place, and would have given Henry the right to occupy it on Richard's behalf.[312] To put additional pressure on Louis, Henry mobilised his armies for war.[310] The papacy intervened and, probably as Henry had planned, the two kings were encouraged to sign a non-aggression treaty in September 1177, under which they promised to undertake a joint crusade.[312] The ownership of the Auvergne and parts of the Berry were put to an arbitration panel, which reported in favour of Henry; Henry followed up this success by purchasing La Marche from the local count.[313] This expansion of Henry's empire once again threatened French security and promptly put the new peace at risk.[314]

Family tensions

In the late 1170s Henry focused on trying to create a stable system of government, increasingly ruling through his family, but tensions over the succession arrangements were never far away, ultimately leading to a fresh revolt.[315] Having quelled the left-over rebels from the Great Revolt, Richard was recognised by Henry as the Duke of Aquitaine in 1179.[316] In 1181 Geoffrey finally married Constance of Brittany and became Duke of Brittany; by now most of Brittany accepted Angevin rule, and Geoffrey was able to deal with the remaining disturbances on his own.[317] John had spent the Great Revolt travelling alongside his father and most observers now began to regard the prince as Henry's favourite child.[318] Henry began to grant John more lands, mostly at various nobles' expense, and in 1177 made him the Lord of Ireland.[319] Meanwhile, Young Henry spent the end of the decade travelling in Europe, taking part in tournaments and playing only a passing role in either government or Henry and Richard's military campaigns; he was increasingly dissatisfied with his position and lack of power.[320]

By 1182 Young Henry reiterated his previous demands: he wanted to be granted lands, for example the Duchy of Normandy, which would allow him to support himself and his household with dignity.[321] Henry refused, but agreed to increase his son's allowance. This was not enough to placate Young Henry.[321] With trouble clearly brewing, Henry attempted to defuse the situation by insisting that Richard and Geoffrey give homage to Young Henry for their lands.[322] Richard did not believe that Young Henry had any claim over Aquitaine and refused to give homage. Henry forced Richard to give homage, but Young Henry angrily refused to accept it.[323] He formed an alliance with some of the disgruntled barons of the Aquitaine who were unhappy with Richard's rule, and Geoffrey sided with him, raising a mercenary army in Brittany to threaten Poitou.[324] Open war broke out in 1183 and Henry and Richard led a joint campaign into Aquitaine: before they could conclude it, Young Henry caught a fever and died, bringing a sudden end to the rebellion.[325]

With his eldest son dead, Henry rearranged the plans for the succession: Richard was to be made king of England, although without any actual power until the death of his father. Geoffrey would have to retain Brittany, as he held it by marriage, so Henry's favourite son John would become the Duke of Aquitaine in place of Richard.[319] Richard refused to give up Aquitaine; he was deeply attached to the duchy, and had no desire to exchange this role for the meaningless one of being the junior King of England.[326] Henry was furious, and ordered John and Geoffrey to march south and retake the duchy by force.[319] The short war ended in stalemate and a tense family reconciliation at Westminster in England at the end of 1184.[327] Henry finally got his own way in early 1185 by bringing Eleanor to Normandy to instruct Richard to obey his father, while simultaneously threatening to give Normandy, and possibly England, to Geoffrey.[328] This proved enough and Richard finally handed over the ducal castles in Aquitaine to Henry.[329]

Meanwhile, John's first expedition to Ireland in 1185 was not a success. Ireland had only recently been conquered by Anglo-Norman forces, and tensions were still rife between Henry's representatives, the new settlers and the existing inhabitants.[330] John offended the local Irish rulers, failed to make allies amongst the Anglo-Norman settlers, began to lose ground militarily against the Irish, and finally returned to England.[330] In 1186 Henry was about to return John to Ireland once again, when news came that Geoffrey had died in a tournament at Paris, leaving two young children; this event once again changed the balance of power between Henry and his remaining sons.[329]

Henry and Philip Augustus

Henry's relationship with his two surviving heirs was fraught. The King had great affection for his youngest son John, but showed little warmth towards Richard and indeed seems to have borne him a grudge after their argument in 1184.[331] The bickering and simmering tensions between Henry and Richard were cleverly exploited by the new French King, Philip II Augustus.[332] Philip had come to power in 1180 and he rapidly demonstrated that he could be an assertive, calculating and manipulative political leader.[333] Initially Henry and Philip Augustus had enjoyed a good relationship. Despite attempts to divide the two, Henry and Philip Augustus agreed to a joint alliance, even though this cost the French King the support of Flanders and Champagne.[334] Philip Augustus regarded Geoffrey as a close friend, and would have welcomed him as a successor to Henry.[335] With the death of Geoffrey, the relationship between Henry and Philip broke down.[336]

In 1186, Philip Augustus demanded that he be given custody of Geoffrey's children and Brittany, and insisted that Henry order Richard to withdraw from Toulouse, where he had been sent with an army to apply new pressure on Philip's uncle, Raymond.[337] Philip threatened to invade Normandy if this did not happen.[337] He also reopened the question of the Vexin which had formed part of Marguerite's dowry several years before; Henry still occupied the region and now Philip insisted that Henry either complete the long agreed Richard-Alys marriage, or return Margaret's dowry.[338] Philip invaded the Berry and Henry mobilised a large army which confronted the French at Châteauroux, before papal intervention brought a truce.[339] During the negotiations, Philip suggested to Richard that they should ally against Henry, marking the start of a new strategy to divide the father and son.[340]

Philip's offer coincided with a crisis in the Levant. In 1187 Jerusalem surrendered to Saladin and calls for a new crusade swept Europe.[341] Richard was enthusiastic and announced his intention to join the crusade, and Henry and Philip announced their similar intent at the start of 1188.[332] Taxes began to be raised and plans made for supplies and transport.[332] Richard was keen to start his crusade, but was forced to wait for Henry to make his arrangements.[342] In the meantime, Richard set about crushing some of his enemies in Aquitaine in 1188, before once again attacking the Count of Toulouse.[342] Richard's campaign undermined the truce between Henry and Philip and both sides again mobilised large forces in anticipation of war.[343] This time Henry rejected Philip's offers of a short-term truce in the hope of convincing the French King to agree to a long-term peace deal. Philip refused to consider Henry's proposals.[344] A furious Richard believed that Henry was stalling for time and delaying the departure of the crusade.[344]

Death

The relationship between Henry and Richard finally dissolved into violence shortly before Henry's death. Philip held a peace conference in November 1188, making a public offer of a generous long-term peace settlement with Henry, conceding to his various territorial demands, if Henry would finally marry Richard and Alys and announce Richard as his recognised heir.[345] Henry refused the proposal, whereupon Richard himself spoke up, demanding to be recognised as Henry's successor.[345] Henry remained silent and Richard then publicly changed sides at the conference and gave formal homage to Philip in front of the assembled nobles.[346]

The papacy intervened once again to try to produce a last-minute peace deal, resulting in a fresh conference at La Ferté-Bernard in 1189.[347] By now Henry was suffering from a bleeding ulcer that would ultimately prove fatal.[348] The discussions achieved little, although Henry is alleged to have offered Philip that John, rather than Richard, could marry Alys, reflecting the rumours circulating over the summer that Henry was considering openly disinheriting Richard.[347] The conference broke up with war appearing likely, but Philip and Richard launched a surprise attack immediately afterwards during what was conventionally a period of truce.[349]

Henry was caught by surprise at Le Mans but made a forced march north to Alençon, from where he could escape into the safety of Normandy.[350] Suddenly, Henry turned back south towards Anjou, against the advice of his officials.[351] The weather was extremely hot, the King was increasingly ill and he appears to have wanted to die peacefully in Anjou rather than fight yet another campaign.[351] Henry evaded the enemy forces on his way south and collapsed in his castle at Chinon.[352] Philip and Richard were making good progress, not least because it was now obvious that Henry was dying and that Richard would be the next king, and the pair offered negotiations.[351] They met at Ballan, where Henry, only just able to remain seated on his horse, agreed to a complete surrender: he would do homage to Philip; he would give up Alys to a guardian and she would marry Richard at the end of the coming crusade; he would recognise Richard as his heir; he would pay Philip compensation, and key castles would be given to Philip as a guarantee.[351]

Henry was carried back to Chinon on a litter, where he was informed that John had publicly sided with Richard in the conflict.[353] This desertion proved the final shock and the King finally collapsed into a fever, regaining consciousness only for a few moments, during which he gave confession.[353] He died on 6 July 1189, aged 56; he had wished to be interred at Grandmont Abbey in the Limousin, but the hot weather made transporting his body impractical and he was instead buried at the nearby Fontevraud Abbey.[353]

Legacy

In the immediate aftermath of Henry's death, Richard successfully claimed his father's lands; he later left on the Third Crusade, but never married Alys as he had agreed with Philip Augustus. Eleanor was released from house arrest and regained control of Aquitaine, where she ruled on Richard's behalf.[354] Henry's empire did not survive long and collapsed during the reign of his youngest son John, when Philip captured all of the Angevin possessions in France except Gascony. This collapse had various causes, including long-term changes in economic power, growing cultural differences between England and Normandy but, in particular, the fragile, familial nature of Henry's empire.[355]

Henry was not a popular king and few expressed much grief on news of his death.[356] Writing in the 1190s, William of Newburgh commented that "in his own time he was hated by almost everyone"; Henry was widely criticised by his own contemporaries, even within his own court.[357] Many of the changes he introduced during his long rule had major long-term consequences. His legal changes are generally considered to have laid the basis for English Common Law, the Exchequer court being a forerunner of the later Common Bench at Westminster.[358] Henry's itinerant justices also influenced his contemporaries' legal reforms: Philip Augustus' creation of itinerant bailli, for example, clearly drew on the Henrician model.[359] Henry's intervention in Brittany, Wales and Scotland also had a significant long-term impact on the development of their societies and governmental systems.[360]

Historiography

Henry and his reign have attracted historians for many years.[361] In the 18th century the historian David Hume argued that Henry's reign was pivotal to creating a genuinely English monarchy and, ultimately, a unified Britain.[362] Henry's role in the Becket controversy was considered relatively praiseworthy by Protestant historians of the period, while his disputes with the French King, Louis, also attracted positive patriotic comment.[363] In the Victorian period there was a fresh interest in the personal morality of historical figures and scholars began to express greater concern over aspects of Henry's behaviour, including his role as a parent and husband.[364] The King's role in the death of Becket attracted particular criticism.[365] Late-Victorian historians, with increasing access to the documentary records from the period, stressed Henry's contribution to the evolution of key English institutions, including the development of the law and the exchequer.[366] William Stubbs' analysis led him to label Henry as a "legislator king", responsible for major, long-lasting reforms in England.[367] Influenced by the contemporary growth of the British Empire, historians such as Kate Norgate undertook detailed research into Henry's continental possessions, creating the term "the Angevin Empire" in the 1880s.[368]

Twentieth-century historians challenged many of these conclusions. In the 1950s Jacques Boussard and John Jolliffe, among others, examined the nature of Henry's "empire"; French scholars in particular analysed the mechanics of how royal power functioned during this period.[369] The Anglocentric aspects of many histories of Henry were challenged from the 1980s onwards, with efforts made to bring together British and French historical analysis of the period.[370] More detailed study of the written records left by Henry has cast doubt on some earlier interpretations: Robert Eyton's ground-breaking 1878 work tracing Henry's itinerary through deductions from the pipe rolls, for example, has been criticised as being too certain a way of determining location or court attendance.[371] Although many more of Henry's royal charters have been identified, the task of interpreting these records, the financial information in the pipe rolls and wider economic data from the reign is understood to be more challenging than once thought.[372] Significant gaps in historical analysis of Henry remain, especially the nature of his rule in Anjou and the south of France.[373]

Popular culture

Henry II appears as a character in several modern plays and films. He is a central character in James Goldman's 1966 play The Lion in Winter, set in 1183 and presenting an imaginary encounter between Henry's immediate family and Philip Augustus over Christmas at Chinon. The 1968 film adaptation communicates the modern popular view of Henry as a somewhat sacrilegious, fiery and determined king although, as Goldman acknowledges, Henry's passions and character are essentially fictional.[374]