Early Christian inscriptions

Early Christian inscriptions are the epigraphical remains of early Christianity. They are a valuable source of information in addition to the writings of the Church Fathers regarding the development of Christian thought and life in the first six centuries of the religion's existence.[2] The three main types are sepulchral inscriptions, epigraphic records, and inscriptions concerning private life.

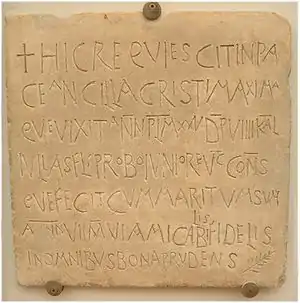

Here rests in peace, Maxima a servant of Christ who lived about 25 years and (was) laid (to rest) 9 days before the Kalends of July of the year when the senator Flavius Probus the younger was consul (June 23rd, 525).[1] She lived with her husband (for) seven years and six months. (She was) most friendly, loyal in everything, good and prudent.

General characteristics

Materials

The materials on which early Christian inscriptions were written were the same as those used for other inscriptions in antiquity. For sepulchral inscriptions and epigraphic records, the substance commonly employed was stone of different kinds, native or imported. The use of metal was less common. When the inscription is properly cut into the stone, it is called a titulus or marble; if merely scratched on the stone, the Italian word graffito is used; a painted inscription is called dipinto, and a mosaic inscription—such as those found largely in North Africa, Spain, and the East—are called opus musivum. It was a common practice in the Greco-Roman world to make use of slabs already inscribed, that is, to take the reverse of a slab already used for an inscription for the inscribing of a Christian one; such a slab is called an opisthograph.

The form of the Christian inscriptions does not differ from that of the non-Christian inscriptions that were contemporary with them, except when sepulchral in character, and then only in the case of the tituli of the catacombs. The forms of stone sepulchral inscriptions differ in the Greek East and Latin West. The most common form in the East was the upright "stele" (Greek: στήλη, a block or slab of stone), frequently ornamented with a fillet or a projecting curved moulding; in the West a slab for the closing of the grave was often used. Thus the majority of the graves (loculi) in the catacombs were closed with thin, rectangular slabs of terracotta or marble; the graves called arcosolia were covered with heavy, flat slabs, while on the sarcophagi a panel (tabula) or a disk (discus) was frequently reserved on the front wall for an inscription.

Artistic value

The majority of the early Christian inscriptions, viewed from a technical and paleographical standpoint, give evidence of artistic decay: this applies especially to the tituli of the catacombs, which are, as a rule, less finely executed than the non-Christian work of the same time. A striking exception is formed by the Damasine letters introduced in the 4th century by Furius Dionysius Filocalus, the calligraphist of Pope Damasus I. The other forms of letters did not vary essentially from those employed by the ancients. The most important was the classical capital writing, customary from the time of Augustus; from the 4th century on it was gradually replaced by the uncial writing, the cursive characters being more or less confined to graffito inscriptions.

Language

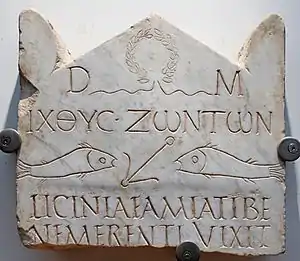

Latin inscriptions are the most numerous. In the East, Greek was commonly employed, interesting dialects being occasionally found, as in the Christian inscriptions from Nubia in southern Egypt that were deciphered in the 19th century. Special mention should also be made of the Coptic inscriptions. The text is very often shortened by means of signs and abbreviations. At any early date, Christian abbreviations were found side by side with those traditionally used in connection with the religions of the Roman Empire. One of the most common was D.M. for Diis Manibus, "to the protecting Deities of the Lower World." The phrase presumably lost its original religious meaning and became a conventional formula as used by the early Christians. Most of the time, dates of Christian inscriptions must be judged from context, but when dates are given, they appear in Roman consular notation, that is, by naming the two consuls who held office that year. The method of chronological computation varied in different countries. The present Dionysian chronology does not appear in the early Christian inscriptions.

Sepulchral inscriptions

The earliest of these epitaphs are characterized by their brevity, only the name of the dead being given. Later a short acclamation was added, such as "in God" or "in Peace." From the end of the 2nd century, the formulae were enlarged by the addition of family names and the date of burial. In the third and fourth centuries, the text of the epitaphs was expanded with the age of the deceased, the year (reckoned according to the consuls in office), and laudatory epithets. For these particulars each of the regions comprising the Roman empire had its own distinct expressions, contractions, and acclamations.

Large use was made of symbolism. Thus the open cross is found in the epitaphs of the catacombs as early as the 2nd century, and from the 3rd to the 6th century the monogrammatic cross in its various forms appears as a regular part of the epitaphs. The cryptic emblems of primitive Christianity are also used in the epitaphs: the fish (Christ), the anchor (hope), the palm (victory), and the representation of the soul in the other world as a female figure with arms extended in prayer (orans).

Beginning with the 4th century, after the Church gained hegemony over the Empire, the language of the epitaphs became more frank and open. Emphasis was laid upon a life according to the dictates of Christian faith, and prayers for the dead were added to the inscription. The prayers inscribed thus early on the sepulchral slabs reproduce in large measure the primitive liturgy of the funeral service. They implore for the dead eternal peace and a place of refreshment (refrigerium), invite to the heavenly love-feast (Agape), and wish the departed the speedy enjoyment of the light of Paradise, and the fellowship of God and the saints.

A perfect example of this kind of epitaph is that of the Egyptian monk Schenute; it is taken verbally from an ancient Greek liturgy. It begins with the doxology, "In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost, Amen", and continues:

May the God of the spirit and of all flesh, Who has overcome death and trodden Hades under foot, and has graciously bestowed life on the world, permit this soul of Father Schenute to attain to rest in the bosom of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, in the place of light and of refreshment, where affliction, pain, and grief are no more. O gracious God, the lover of men, forgive him all the errors which he has committed by word, act, or thought. There is indeed no earthly pilgrim who has not sinned, for Thou alone, O God, art free from every sin.

The epitaph repeats the doxology at the close, and adds the petition of the scribe: "O Savior, give peace also to the scribe." When the secure position of the Church assured greater freedom of expression, the non-religious part of the sepulchral inscriptions was also enlarged. In Western Europe and in the East it was not unusual to note, both in the catacombs and in the cemeteries above ground, the purchase or gift of the grave and its dimensions. Traditional minatory formulae against desecration of the grave or its illegal use as a place of further burial also came into Christian use.

Historical and theological inscriptions

Many of the early Christian sepulchral inscriptions provide information concerning the original development of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Thus, for example, from the earliest times we meet in them all the hierarchical grades from the door-keeper (ostiarius) and lector up to the Pope. A number of epitaphs of the early popes (Pontianus, Anterus, Fabianus, Cornelius, Lucius, Eutychianus, Caius) were found in the so-called "Papal Crypt" in the Catacomb of St. Callistus on the Via Appia, rediscovered by De Rossi. Numbers of early epitaphs of bishops have been found from Germany to Nubia. Priests are frequently mentioned, and reference is often made to deacons, subdeacons, exorcists, lectors, acolytes, fossores or gravediggers, alumni or adopted children. The Greek inscriptions of Western Europe and the East yield especially interesting material; in them is found, in addition to other information, mention of archdeacons, archpriests, deaconesses, and monks. Besides catechumens and neophytes, reference is also made to virgins consecrated to God, nuns, abbesses, holy widows, one of the last-named being the mother of Pope Damasus I, the restorer of the catacombs. Epitaphs of martyrs and tituli mentioning the martyrs are not found as frequently as one would expect, especially in the Roman catacombs. It may be that during periods of persecution, Christians had to give secret burial to the remains of their martyrs.

Another valuable repertory of Catholic theology is found in the dogmatic inscriptions in which all important dogmas of the Church meet (incidentally) with monumental confirmation. The monotheism of the worshippers of the Word — or Cultores Verbi, as the early Christians liked to style themselves — and their belief in Christ are well expressed even in the early inscriptions. Very ancient inscriptions emphasize the most profound of Catholic dogmas, the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Two early inscriptions are particularly notable in this regard, the epitaph of Abercius, Bishop of Hieropolis in Phrygia (2nd century), and the somewhat later epitaph of Pectorius at Autun in Gaul. The inscription of Abercius speaks of the fish (Christ) caught by a holy virgin, which serves as food under the species of bread and wine; it speaks, further, of Rome, where Abercius visited the chosen people, the Church par excellence. This important inscription was at first controversial among scholars, and some non-Catholic archeologists sought to find in it a tendency to syncretism, that is, an accommodation of Christianity with earlier and other religions practiced within the Roman Empire. Now, however, its purely Christian character is almost universally acknowledged. The original was presented by Sultan Abdul Hamid to Leo XIII, and is preserved in the Vatican Museums (ex Lateranense collection).

Early Christian inscriptions also provide evidence for the Catholic doctrine of the Resurrection, the sacraments, the veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the primacy of the Apostolic See in Rome. It would be difficult to overestimate the importance of these evidences, for they are always entirely incidental elements of the sepulchral inscriptions, all of which were pre-eminently eschatological in their purpose.

Poetical and official inscriptions

The purely literary side of these monuments is not insignificant. Many inscriptions have the character of public documents; others are in verse, either taken from well-known poets, or at times the work of the person erecting the memorial. Fragments of classical poetry, especially quotations from Virgil, are occasionally found. The most famous composer of poetical epitaphs in Christian antiquity was Pope Damasus I (366–384), mentioned above. He repaired the neglected tombs of the martyrs and the graves of distinguished persons who had lived before the Constantinian epoch, and adorned these burial places with metrical epitaphs in a peculiarly beautiful lettering. Nearly all the larger cemeteries of Rome owe to this pope large stone tablets of this character, several of which have been preserved in their original form or in fragments. Besides verses on his mother Laurentia and his sister Irene, he wrote an autobiographical poem addressed to Christ:

"Thou Who stillest the waves of the deep, Whose power giveth life to the seed slumbering in the earth, who didst awaken Lazarus from the dead and give back the brother on the third day to the sister Martha; Thou wilt, so I believe, awake Damasus from death."

Eulogies in honor of the Roman martyrs form the most important division of the Damasine inscriptions. They are written in hexameters, a few in pentameters. The best known celebrate the temporary burial of the two chief Apostles in the Platonia under the basilica of St. Sebastian on the Via Appia, the martyrs Hyacinth and Protus in the Via Salaria Antiqua, Pope Marcellus in the Via Salaria Nova, Saint Agnes in the Via Nomentana, also Saints Laurence, Hippolytus, Gorgonius, Marcellinus and Peter, Eusebius, Tarsicius, Cornelius, Eutychius, Nereus and Achilleus, Felix and Adauctus.

Damasus also placed a metrical inscription in the baptistery of the Vatican, and set up others in connexion with various restorations, for instance an inscription on a stairway of the cemetery of Saint Hermes. Altogether there have been preserved as the work of Damasus more than one hundred epigrammata, some of them originals and others written copies. More than one half are probably correctly ascribed to him, even though after his death Damasine inscriptions continued to be set up in the beautiful lettering invented by Damasus or rather by his calligrapher Furius Dionysius Filocalus. Some of the inscriptions, which imitate the lettering of Filocalus, make special and laudatory mention of the pope who had done so much for the catacombs. Among these are the inscriptions of Pope Vigilius (537-55), a restorer animated by the spirit of Damasus. Some of his inscriptions are preserved in the Lateran Museum. These inscriptions as a rule are public and official in character. Other inscriptions served as official records of the erection of Christian edifices such as churches and baptisteries. Ancient Roman examples of this kind include the inscribed tablet dedicated by Boniface I at the beginning of the 5th century to St. Felicitas, to whom the pope ascribed the settlement of the schism of Eulalius, and the inscription (still visible) of Pope Sixtus III in the Lateran baptistery. The Roman custom was soon copied in all parts of the empire. At Thebessa in Northern Africa there were found fragments of a metrical inscription once set up over a door, and in almost exact verbal agreement with the text of an inscription in a Roman church. Both the basilica of Nola and the church at Primuliacum in Gaul bore the same distich:

Pax tibi sit quicunque Dei penetralia Christi,

- pectore pacifico candidus ingrederis.

("Peace be to thee whoever enterest with pure and gentle heart into the sanctuary of Christ God.")

In such inscriptions the church building is generally referred to as domus Dei ("the house of God") or domus orationis ("the house of prayer"). The customary Greek term Kyriou ("of the Lord") was found in the basilica of the Holy Baths, one of the basilicas of the ancient Egyptian town of Menas. In Northern Africa, especially, passages from the psalms frequently occur in Christian inscriptions. The preference in the East was for inscriptions executed in mosaic; such inscriptions were also frequent in Rome, where, it is well known, the art of mosaic reached very high perfection in Christian edifices. An excellent and well-known example is the still extant original inscription of the 5th century on the wall of the interior of the Roman basilica of Santa Sabina on the Aventine over the entrance to the nave. This monumental record in mosaic contains seven lines in hexameters. On each side of the inscription is a mosaic figure: one is the Ecclesia ex gentibus ("Church of the Nations"), the other the Ecclesia ex circumcisione ("Church of the Circumcision"). The text refers to the pontificate of Celestine I, during which period an Illyrian priest named Peter founded the church.

Other parts of the early Christian churches such as roofs and walls were also occasionally decorated with inscriptions. It was also customary to decorate with inscriptions the lengthy cycles of frescoes depicted on the walls of churches. Fine examples of such inscriptions are preserved in the Dittochaeon of Prudentius, in the Ambrosian tituli, and in the writings of Paulinus of Nola.

Many dedicatory inscriptions belong to the eighth and ninth centuries, especially in Rome, where in the eighth century numerous bodies of saints were transferred from the catacombs to the churches of the city.

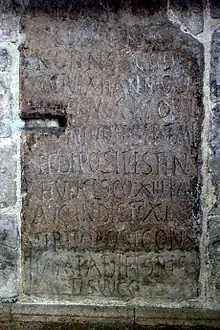

Graffiti

Although graffiti are devoid of monumental character, writings scratched or scrawled on walls or other surfaces can be of great historical importance. Many are preserved in the catacombs and on various early Christian monuments. Especially notable are the ruins of the fine edifices of the town of Menas in the Egyptian Mareotis.[3] The graffiti, in turn, help to illustrate the literary sources of the life of the early Christians.

See also

Bibliography

- de Rossi, Inscriptiones Christianae urbis Romae septimo saeculo antiquiores (Rome, 1861)

- Le Blant, Manuel d'épigraphie chrétienne (Paris, 1869)

- Ritter, De compositione titulorum christianorum sepulcralium (Berlin, 1877)

- M'Caul, Christian Epitaphs of the First Six Centuries (London, 1869)

- James Spencer Northcote and William R. Brownlow, Epitaphs of the Catacombs (London, 1879)

- Kaufmann, Handbuch der christlichen Archäologie, pt. III, Epigraphische Denkmäler (Paderborn, 1905)

- Systus, Notiones archæologiæ Christian, vol. III, pt. I, Epigraphia (Rome, 1909).

- Aste Antonio, Gli epigrammi di papa Damaso I. Traduzione e commento, Libellula edizioni, collana Università (Tricase, Lecce 2014).

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Early Christian Inscriptions". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. The original article was written by Carl Maria Kaufmann.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Early Christian Inscriptions". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. The original article was written by Carl Maria Kaufmann.

Notes

- "deposit.ddb.de". Archived from the original on 2011-08-20. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- Although the period of Early Christianity is most often dated up to the early 4th century — that is, before the era of Christian hegemony in the Roman Empire — the term "early Christian" can also be applied through the 6th or 7th century.

- Proceedings of the Society for Biblical Archæology (1907), pp. 25, 51, 112.

*