Economic integration

Economic integration is the unification of economic policies between different states, through the partial or full abolition of tariff and non-tariff restrictions on trade.

| Part of a series on |

| World trade |

|---|

|

The trade-stimulation effects intended by means of economic integration are part of the contemporary economic Theory of the Second Best: where, in theory, the best option is free trade, with free competition and no trade barriers whatsoever. Free trade is treated as an idealistic option, and although realized within certain developed states, economic integration has been thought of as the "second best" option for global trade where barriers to full free trade exist.

Economic integration is meant in turn to lead to lower prices for distributors and consumers with the goal of increasing the level of welfare, while leading to an increase of economic productivity of the states.

Objective

There are economic as well as political reasons why nations pursue economic integration. The economic rationale for the increase of trade between member states of economic unions rests on the supposed productivity gains from integration. This is one of the reasons for the development of economic integration on a global scale, a phenomenon now realized in continental economic blocs such as ASEAN, NAFTA, SACN, the European Union, AfCFTA and the Eurasian Economic Community; and proposed for intercontinental economic blocks, such as the Comprehensive Economic Partnership for East Asia and the Transatlantic Free Trade Area.

Comparative advantage refers to the ability of a person or a country to produce a particular good or service at a lower marginal and opportunity cost over another. Comparative advantage was first described by David Ricardo who explained it in his 1817 book On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation in an example involving England and Portugal.[1] In Portugal it is possible to produce both wine and cloth with less labour than it would take to produce the same quantities in England. However the relative costs of producing those two goods are different in the two countries. In England it is very hard to produce wine, and only moderately difficult to produce cloth. In Portugal both are easy to produce. Therefore, while it is cheaper to produce cloth in Portugal than England, it is cheaper still for Portugal to produce excess wine, and trade that for English cloth. Conversely England benefits from this trade because its cost for producing cloth has not changed but it can now get wine at a lower price, closer to the cost of cloth. The conclusion drawn is that each country can gain by specializing in the good where it has comparative advantage, and trading that good for the other.

Economies of scale refers to the cost advantages that an enterprise obtains due to expansion. There are factors that cause a producer's average cost per unit to fall as the scale of output is increased. Economies of scale is a long run concept and refers to reductions in unit cost as the size of a facility and the usage levels of other inputs increase.[2] Economies of scale is also a justification for economic integration, since some economies of scale may require a larger market than is possible within a particular country — for example, it would not be efficient for Liechtenstein to have its own car maker, if they would only sell to their local market. A lone car maker may be profitable, however, if they export cars to global markets in addition to selling to the local market.

Besides these economic reasons, the primary reasons why economic integration has been pursued in practise are largely political. The Zollverein or German Customs Union of 1867 paved the way for partial German unification under Prussian leadership in 1871. "Imperial free trade" was (unsuccessfully) proposed in the late 19th century to strengthen the loosening ties within the British Empire. The European Economic Community was created to integrate France and Germany's economies to the point that they would find it impossible to go to war with each other.

Success factors

Among the requirements for successful development of economic integration are "permanency" in its evolution (a gradual expansion and over time a higher degree of economic/political unification); "a formula for sharing joint revenues" (customs duties, licensing etc.) between member states (e.g., per capita); "a process for adopting decisions" both economically and politically; and "a will to make concessions" between developed and developing states of the union.

A "coherence" policy is a must for the permanent development of economic unions, being also a property of the economic integration process. Historically the success of the European Coal and Steel Community opened a way for the formation of the European Economic Community (EEC) which involved much more than just the two sectors in the ECSC. So a coherence policy was implemented to use a different speed of economic unification (coherence) applied both to economic sectors and economic policies. Implementation of the coherence principle in adjusting economic policies in the member states of economic block causes economic integration effects.

Economic theory

The framework of the theory of economic integration was laid out by Jacob Viner (1950) who defined the trade creation and trade diversion effects, the terms introduced for the change of interregional flow of goods caused by changes in customs tariffs due to the creation of an economic union. He considered trade flows between two states prior and after their unification, and compared them with the rest of the world. His findings became and still are the foundation of the theory of economic integration. The next attempts to enlarge the static analysis towards three states+world (Lipsey, et al.) were not as successful.

The basics of the theory were summarized by the Hungarian economist Béla Balassa in the 1960s. As economic integration increases, the barriers of trade between markets diminish. Balassa believed that supranational common markets, with their free movement of economic factors across national borders, naturally generate demand for further integration, not only economically (via monetary unions) but also politically—and, thus, that economic communities naturally evolve into political unions over time.

The dynamic part of international economic integration theory, such as the dynamics of trade creation and trade diversion effects, the Pareto efficiency of factors (labor, capital) and value added, mathematically was introduced by Ravshanbek Dalimov. This provided an interdisciplinary approach to the previously static theory of international economic integration, showing what effects take place due to economic integration, as well as enabling the results of the non-linear sciences to be applied to the dynamics of international economic integration.

Equations describing:

- enforced oscillations of a pendulum with friction;

- predator-prey oscillations;

- heat and/or gas spatial dynamics (the heat equation and Navier-Stokes equations)

were successfully applied towards:

- the dynamics of GDP;

- price-output dynamics and the dynamic matrix of the outputs of an economy;

- regional and inter-regional migration of labor income and value added, and to trade creation and trade diversion effects (inter-regional output flows).

The straightforward conclusion from the findings is that one may use the accumulated knowledge of the exact and natural sciences (physics, biodynamics, and chemical kinetics) and apply them towards the analysis and forecasting of economic dynamics.

Dynamic analysis has started with a new definition of gross domestic product (GDP), as a difference between aggregate revenues of sectors and investment (a modification of the value added definition of the GDP). It was possible to analytically prove that all the states gain from economic unification, with larger states receiving less growth of GDP and productivity, and vice versa concerning the benefit to lesser states. Although this fact has been empirically known for decades, now it was also shown as being mathematically correct.

A qualitative finding of the dynamic method is the similarity of a coherence policy of economic integration and a mixture of previously separate liquids in a retort: they finally get one colour and become one liquid. Economic space (tax, insurance and financial policies, customs tariffs, etc.) all finally become the same along with the stages of economic integration.

Another important finding is a direct link between the dynamics of macro- and micro-economic parameters such as the evolution of industrial clusters and the GDP's temporal and spatial dynamics. Specifically, the dynamic approach analytically described the main features of the theory of competition summarized by Michael Porter, stating that industrial clusters evolve from initial entities gradually expanding within their geographic proximity. It was analytically found that the geographic expansion of industrial clusters goes along with raising their productivity and technological innovation.

Domestic savings rates of the member states were observed to strive to one magnitude, and the dynamic method of forecasting this phenomenon has also been developed. Overall dynamic picture of economic integration has been found to look quite similar to unification of previously separate basins after opening intraboundary sluices, where instead of water the value added (revenues) of entities of member states interact.

Stages

.png.webp)

%252C_WTO.png.webp)

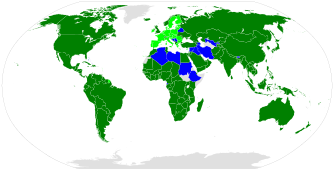

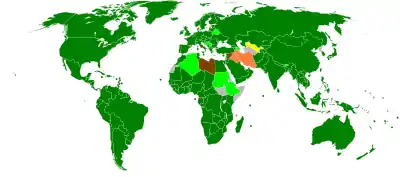

The degree of economic integration can be categorized into seven stages:[3]

- Preferential trading area

- Free-trade area

- Customs union

- Single market

- Economic union

- Economic and monetary union

- Complete economic integration

These differ in the degree of unification of economic policies, with the highest one being the completed economic integration of the states, which would most likely involve political integration as well.

A "free trade area" (FTA) is formed when at least two states partially or fully abolish custom tariffs on their inner border. To exclude regional exploitation of zero tariffs within the FTA there is a rule of certificate of origin for the goods originating from the territory of a member state of an FTA.

A "customs union" introduces unified tariffs on the exterior borders of the union (CET, common external tariffs). A "monetary union" introduces a shared currency. A "common market" add to a FTA the free movement of services, capital and labor.

An "economic union" combines customs union with a common market. A "fiscal union" introduces a shared fiscal and budgetary policy. In order to be successful the more advanced integration steps are typically accompanied by unification of economic policies (tax, social welfare benefits, etc.), reductions in the rest of the trade barriers, introduction of supranational bodies, and gradual moves towards the final stage, a "political union".

[partial] — [substantial] — [none or not applicable]

Global economic integration

Globalization refers to the increasing global relationships of culture, people, and economic activity.

With economics crisis started in 2008 the global economy has started to realize quite a few initiatives on regional level. It is unification between the EU and US, expansion of Eurasian Economic Community (now Eurasia Economic Union) by Armenia and Kyrgyzstan. It is also the creation of BRICS with the bank of its members, and notably high motivation of creating competitive economic structures within Shanghai Organization, also creating the bank with many multi-currency instruments applied. Engine for such fast and dramatic changes was insufficiency of global capital, while one has to mention obvious large political discrepancies witnessed in 2014–2015. Global economy has to overcome this by easing the moves of capital and labor, while this is impossible unless the states will find common point of views in resolving cultural and politic differences which pushed it so far as of now.

Etymology

In economics the word integration was first employed in industrial organisation to refer to combinations of business firms through economic agreements, cartels, concerns, trusts, and mergers—horizontal integration referring to combinations of competitors, vertical integration to combinations of suppliers with customers. In the current sense of combining separate economies into larger economic regions, the use of the word integration can be traced to the 1930s and 1940s.[4] Fritz Machlup credits Eli Heckscher, Herbert Gaedicke and Gert von Eyern as the first users of the term economic integration in its current sense. According to Machlup, such usage first appears in the 1935 English translation of Hecksher's 1931 book Merkantilismen (Mercantilism in English), and independently in Gaedicke's and von Eyern's 1933 two-volume study Die produktionswirtschaftliche Integration Europas: Eine Untersuchung über die Aussenhandelsverflechtung der europäischen Länder.[5]

See also

Notes

- The exact phrase is not found in an online version of that book.

- O'Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003). Economics: Principles in Action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 157. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Page 2, Balassa, Bela. The Theory of Economic Integration (Routledge Revivals). Routledge, 2013.

- Machlup 1977, p. 3.

- Machlup 1977, pp. 4–9.

Bibliography

- Balassa, В. Trade Creation and Trade Diversion in the European Common Market. The Economic Journal, vol. 77, 1967, pp. 1–21.

- Dalimov R.T. Modelling international economic integration: an oscillation theory approach. Trafford, Victoria 2008, 234 p.

- Dalimov R.T. Dynamics of international economic integration: non-linear analysis. Lambert Academic Publishing, 2011, 276 p.; ISBN 978-3-8433-6106-4, ISBN 3-8433-6106-1.

- Johnson, H. An Economic Theory of Protection, Tariff Bargaining and the Formation of Customs Unions. Journal of Political Economy, 1965, vol. 73, pp. 256–283.

- Johnson, H. Optimal Trade Intervention in the Presence of Domestic Distortions, in Baldwin et al., Trade Growth and the Balance of Payments, Chicago, Rand McNally, 1965, pp. 3–34.

- Jovanovich, М. International Economic Integration. Limits and Prospects. Second edition, 1998, Routledge.

- Lipsey, R.G. The Theory of Customs Union: Trade Diversion and Welfare. Economica, 1957, vol. 24, рр.40-46.

- Меаdе, J.E. The Theory of Customs Union.” North Holland Publishing Company, 1956, pp. 29–43.

- Machlup, Fritz (1977). A History of Thought on Economic Integration. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-04298-1.

- Negishi, T. Customs Unions and the Theory of the Second Best. International Economic Review, 1969, vol. 10, pp. 391–398

- Porter M. On Competition. Harvard Business School Press; 1998; 485 pgs.

- Riezman, R. A Theory of Customs Unions: The Three Country–Two Goods Case. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 1979, vol. 115, pp. 701–715.

- Ruiz Estrada, M. Global Dimension of Regional Integration Model (GDRI-Model). Faculty of Economics and Administration, University of Malaya. FEA-Working Paper, № 2004-7

- Tinbergen, J. International Economic Integration. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1954.

- Tovias, A. The Theory of Economic Integration: Past and Future. 2d ECSA-World conference “Federalism, Subsidiarity and Democracy in the European Union”, Brussels, May 5–6, 1994, 10 p.

- Viner, J. The Customs Union Issue. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1950, pp. 41–55.

- INTAL; https://web.archive.org/web/20100516012601/http://www.iadb.org/intal/index.asp?idioma=eng

External links

Media related to Economic integration at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Economic integration at Wikimedia Commons