Education in Mali

Education in Mali is considered a fundamental right of Malians.[1] For most of Mali's history, the government split primary education into two cycles which allowed Malian students to take examinations to gain admission to secondary, tertiary, or higher education.[2] Mali has recently seen large increases in school enrollment due to educational reforms.[2]

Mali has a long history about education, dating back to the years before 1960, when Mali was under the rule of France.[3] After gaining independence, the Malian government made many efforts to incorporate more African and bilingual education into classrooms.[4] Additionally, after the 1990s, when the Malian government shifted from a one party system to a democracy, the government created policies which focused on literacy and educational quality.[5]

In addition to primary public and private schools, other types of schools in Mali include vocational and technical institutions, religious schools, community schools, and schools for those with disabilities.[6] Especially since Islam is the main religion in Mali, madrassas and medersas are two Islamic institutions which many Malians attend.[7] Additionally, community schools have become increasingly popular in this country since they are usually more accessible, especially to rural students, and allow students to engage with their communities.[6] In recent years, many communities have created initiatives to incorporate deaf and disabled students into classrooms.[8]

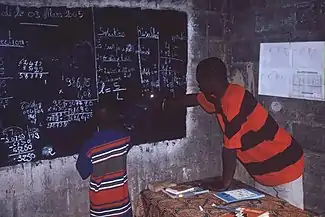

With approximately half of Malians ages 15-24 illiterate, literacy has been an issue of concern for the Malian government.[9] National programs to address this issue focus on first giving students the knowledge they need to read and write.[10] Afterwards, communities and foreign countries try to incorporate post literacy and integrated literacy into educational programs to allow students to utilize their new skills to help the economy and community.[11][12] One famous example of a literacy project Mali took part in is the Experimental World Literacy Program.[12]

The differences between French, Mali's national language, and local languages have caused many problems in education.[10] Access, geographic location, gender bias, and the quality of education are also issues that many Malians face.[13] Food, nutrition, disease, disability, and educational inefficiencies contribute to some of the problems with education in this country.[8][14][15] Nevertheless, there have been many domestic and foreign initiatives to confront some of these issues.[4][16] Additionally, foreign policies, such as those in the United States and France, and community initiatives, such as the mobilization of animatrices, have developed Malian education.[4][16][17]

History

Education during French rule

During the French colonization of West Africa, the French Navy constructed some of the first schools in Mali.[17] In 1877, the French introduced the first public schools to Mali which were collectively known as the Schools of Hostages, a name inspired by the tensions between the French and indigenous chiefs.[3] However, by 1899, these public schools were renamed to the Schools for Sons of Chiefs, or Les Ecoles des Fils des Chefs, as a part of a larger French effort to cooperate with the indigenous population.[17][3] Joseph Gallieni and Louis Archinard are two individuals who contributed to the opening of some of these first schools during the 19th century.[17]

During the French rule of Mali, the education was mainly geared towards teaching information about France and the French language rather than Malian traditions.[3] Many historians and authors, such as Charles Cutter, believe that Malians did not enjoy many rights during this era and faced an identity crisis while assimilating to French culture.[3][18] To avoid this crisis, Malians relied on maintaining oral traditions.[18] Additionally, many Malians sent their children to traditional and Islamic schools in an effort to have their children learn more about the cultural traditions of Mali.[3] For example, in Kayes, after the first French schools opened up, ethnic groups decided to send their children to madrassas and medersas, or private Islamic schools taught in Arabic.[19][7] These ethnic groups, along with many others in Mali, believed that sending children to these schools was a way to make a political and religious statement, acquire merit, and create an African-Muslim identity.[7] In 1906, the French created their own version of medersas in Djenné and Timbuktu in the French language, which allowed students to pursue career opportunities within the French administration.[7]

The French passed the Ordinance of November 24th, 1903 which developed public education in French West Africa.[17] This was part of a larger effort to create more primary and regional schools.[3] Specifically, this ordinance developed more schools at various levels ranging from the local level to the secondary and vocational levels.[17] Additionally, it allowed teachers to gain more experience and training.[17] Although this ordinance made major breakthroughs in the development of schools, historians such as Boniface Obichere cite it as being discriminatory against native Malians.[17]

Education post-independence

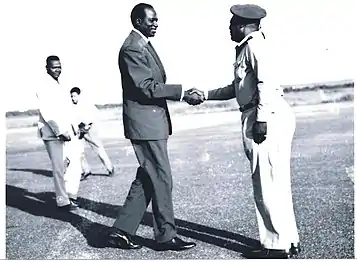

In 1960, Mali gained independence from France.[3] Immediately following independence, only about a tenth of Malians were literate and attending school.[3] During this time period, many West African politicians were a part of the Rassemblement Démocratique Africain, which was a political group that partially focused on developing educational and literacy opportunities in West African communities.[17] In fact, Modibo Keïta, the first President of Mali, used this ideology along with his socialist philosophy to develop a new educational system in 1962.[17] This system focused on tooling Malians with skills to contribute to the nation's economy.[17] Additionally, it split up the educational structure into two ministries.[17] Specifically, the Ministry of Basic Education, Youth and Sports oversaw primary education whereas the Ministry of Higher and Secondary Education and Scientific Research was put in charge of education higher than the primary level.[17]

In 1980, when Mali was governed under a dictatorship, literacy percentages fell to levels as low as 13.6% for adults and 25.6% for Malians ages 15 to 24.[3] However, a democratic movement in the 1990s resulted in the government making education more accessible by lowering educational fees and increasing the production of schools.[20] By 2000, those same literacy percentages increased by 26.7% and 38.7% respectively.[3] Additionally, by 1999, the government officially recognized bilingual education since most families spoke in one of fifty-six local languages.[8] Nevertheless, as mentioned in a study by Jaimie Bleck on the Malian capital of Bamako, this liberalization of education led to the crowding of students in public schools and a shift in interest towards private schools.[20] For example, some sections of Bamako have over 40% of students enrolled in private schools.[19]

Educational structure

Cycles of schooling

In the 1980s, Malian education followed a two cycle system.[13][2] During the first cycle, children began their education in state schools at the age of seven or eight for six years before taking the CEP Exam which stands for the Certificate de Fin d'Etudes du Premier Cycle in French.[13][2] Many students found the first cycle to be difficult, especially because Malian schools were primarily in French, a language that most Malians, especially those that lived in rural areas, had little experience with.[13] Thus, 1 in 6 students in the first cycle opted to attend medersas.[13] Afterwards, a student who successfully completed the second cycle of education, which took three years, was eligible to take an examination known as the Diploma in Basic Education also known as the Diplôme d'Etudes Fondamentales.[13][2] After 2012, the government merged these two cycles into one, but the examinations that the students had to take stayed in place.[2] Currently, children ages 7 to 15 are required to attend school, which lasts from October to June every year.[21]

Government hierarchy

The Malian education system is hierarchical in governance.[2] The National Minister and the National Directorate of Higher Education are both in charge of public universities at the national level.[2] The AE which stands for the Académies d'Enseignment heads regional education.[2] Additionally, the CAP or Centres for Pedagogical Activities is responsible for local education.[2]

Public education is directed and funded from the national level.[22] The Ministry has two Ministerial level officers, each heading one independent arm of the Ministry.[22] The Ministre de L’Education de Base, de L’Alphabétisation et des Langues Nationales (Ministry of Basic Education, Literacy, and National Languages) is responsible for Primary education, literacy programs outside the schools, and the promotion and standardization of "National Languages", such as Bambara and Tamcheq, other than the official language, French.[22]

The Ministre des Enseignements Secondaire, supérieur et de la Recherche scientifique (Ministry of Secondary and Superior Education, and Scientific Research) is tasked with government Secondary schools, university, and an array of vocational, technical, and research centres.[22] As of 2008, the Minister of Basic Education, Literacy, and National Languages was Sidibe Aminata Diallo[23] and the Minister of Secondary and Superior Education, and Scientific Research was Amadou Toure.[24]

Primary schools

Public schools

The Malian Ministry of Education is responsible for managing public schools in Mali.[6] These secular schools are taught in Mali's national language, French.[6] Many parents often pay fees for their children to attend these schools which is considered illegal according to Malian law.[6] Additionally, teachers are kept under a contract which limits the amount of training these educators have access to prior to beginning teaching.[6] This leads to frequent strikes, a shortage of teachers, and large class sizes.[6]

Private schools

Compared to their public counterparts, private schools in Mali are more expensive to attend.[6] These extra resources paired with lower amounts of government regulation allow these institutions to have smaller class sizes.[6] They also give students employment connections after graduation.[6] Like public schools, these institutions are also mainly taught in French, but they can be secular or religious.[6] Mali has many private Christian schools which are mainly managed by the Catholic church.[6]

Secondary, tertiary, and higher education

After primary education, students can choose to continue upon their academic track and attend a lycée for three years which ends with an exam called the Baccalaureat.[2] Doing well on this examination can help students gain admission to universities for higher and tertiary education.[2] Conversely, Malian students can take a more pre-professional track and opt to attend a two or four year vocational program to obtain a technical degree.[2] These forms of education have generally diversified over the past few years, since many students are now literate in many different languages such as Arabic, French, Latin, and local languages.[7] One famous example of a long lasting secondary school in Mali is the Higher Technical School.[3]

Increased spending on primary education, especially for children in rural areas and girls, has had the unintended effect of overtaxing the secondary school system. At the end of their primary schooling, students may take entrance exams for secondary school admissions, called the diplôme d’étude fondamentale (Fundamental Studies Diploma or DEF). In 2008 more than 80,000 students passed these exams, yet around 17,000—40% of whom were girls—were denied placement in secondary schools.[25] While the government contends these students should be placed in limited places based on their diploma, their age, and their academic history, some Malians contend that gender discrimination plays a role in denying spots to girls.[25]

Students in Mali pay no tuition fees, but private secondary and vocational schooling may charge $600 a year (in Bamako, 2008), in a nation where the average yearly salary was $500 in 2007 according to the World Bank.[25]

One of the oldest universities in the world — Sankore in Timbuktu — dates back to the 15th century.

The University of Bamako, also known as the University of Mali, is a 1990s aggregation of older institutions of higher education in the Bamako area. Its main campus is in the neighborhood of Badalabougou.

The University includes five Faculties and two institutes:

- The Science and Technology faculty (Faculté des sciences et techniques or FAST),

- The Medical faculty (Faculté de Médecine, de Pharmacie et d’Odento-Stamologie or FMPOS),

- The Humanities, Arts, and Social Science faculty (Faculté des Lettres, Langues, Arts et Sciences Humaines or FLASH),

- The Law and Public Service faculty (Faculté des Sciences Juridiques et Politiques FSJP),

- The Science of Economy and Management Faculty ("Faculté des Sciences Economiques et de Gestion" or FSEG,

- The Institute of Management ( "Institut Universitaire de Management" or IUG),

- The Higher Institute for Training and Applied Research ("Institut Supérieur de Formation et de Recherche Appliquée" or ISFRA).[26]

Islamic education

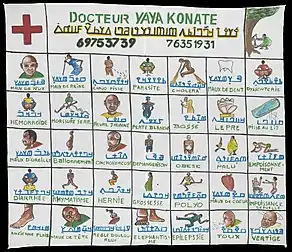

Islamic education began in the Malian religion as early as the 16th century, when Timbuktu had 150 Qur'anic schools.[19] Many Malians, especially those who reside in Bamako, Sikasso, and Kayes, attend madrassas, which are private Islamic schools that are mainly taught in Arabic for primary education.[6] These institutions also teach French, as required by the Malian law, and receive international aid from regions such as the US and Europe.[6] Similarly, many Malians attend informal Qur'anic schools which teach students how to read Arabic through using local languages.[6] These schools do not receive government aid.[6] A medersa also helps students learn how to recite the Qur'an, but additionally provides students with an education about western issues, Islamic, European, and French history, mathematics, and Arabic.[7]

Community education

In the 1990s, the USAID, or United States Agency for International Development, created a community school program mainly for primary education in Mali.[6] These institutions are not for profit and are primarily overseen by community leaders.[6] Community schools are taught in either French or local languages and provide students with technical, vocational, and literacy courses.[20] These schools are generally flexible and cater to the needs of a community.[6] Parents typically pay for their children to attend these institutions through community resources.[6] Nevertheless, community schools have increased the rate of primary education in places which are known for having low enrollment rates, such as Sikasso.[19]

Education for the deaf

Due to the large population of the deaf community in Mali, the Malian government created initiatives to address educational opportunities for deaf students.[8] In 1993, Bala Keita created the EDA or École pour les défients auditifs in Bamako which provides special education to deaf Malians.[8] In the past three decades, Sikasso, Koutiala, Ségou, and Douentza saw an increase in schools for the deaf due to figures such as Dramane Diabaté and Dominique Pinsonneault.[8] One example of a school for the deaf is Jigiya Kalanso.[8]

Vocational and technical education

After primary school, Malians can optionally attend vocational and technical schools which provide pre-professional certificates and education.[17] A few examples of vocational and technical schools include the National School for Engineers, Lycée Technique, Lycée Agricole de Katibougou, the Agricultural Apprenticeship Centers at M'Pessoba and Samanko, and the School for Veterinarians in Bamako. [17][3]

Literacy

Literacy initiatives in Mali occur in three stages: learning to read and write, post literacy, and integrating literacy into life activities.[10] According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or UNESCO, 35.47% of Malians that are 15 years or older are able to read and write as of 2018.[9] Specifically, the 2018 literacy rates for Malians ages 15-24 and 65 years and older were 50.13% and 19.08%, respectively.[9] For each of these three groups, the percentage of the male population that was literate was higher than the percentage of the female population that was literate.[9] Although the government implemented literacy programs immediately after Mali gained independence, these initiatives became much more prominent during the democratic movements of the 1990s.[5] Literacy programs currently have a large presence in rural communities.[10]

Post literacy

Post literacy is defined as the process of helping neo-literates utilize their new knowledge and skills to develop the community and environment.[11] Post literacy efforts in Mali revolve around the idea of functional literacy which focuses on making practical applications of new literacy skills.[11] Functional literacy allows Malians to use their skills for community and national development.[10] Institutions such as the National Directorate of Functional Literacy and Applied Linguistics have been major proponents of providing adequate avenues for Malian neo-literates to practice their new skills.[11] For example, in one specific campaign for neo-literates in the 1990s, the number of neo-literates doubled to 60,282 in a four year span.[11]

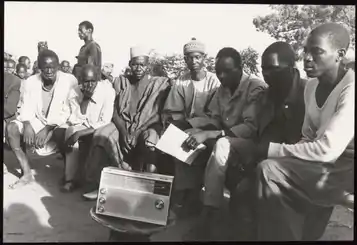

A few examples of resources the National Directorate of Functional Literacy and Applied Linguistics, or DNAFLA, distributes are newspapers, educational booklets, paperbacks, and educational radio broadcasts and films.[11] The DNAFLA diversified their education after beginning the Further Education for Neo-literates program in 1977 which allowed local Malians to develop action plans for post-literacy education.[11] Two examples of trainings that the DNAFLA now offers are education in agriculture and health care.[11] Additionally, many post literacy institutions stress the importance of neo-literates using their skills to make a community impact.[11]

Integrated literacy

Integrated literacy involves pairing literacy efforts with economic development.[12] Mali took part in UNESCO's Experimental World Literacy Program from 1965 to 1975 which involved integrated literacy programs.[12] This was part of a larger effort to incorporate educational reform into government policy.[12] This initiative transformed classrooms into a source of learning about the various economic spheres of Mali and also allowed students to pursue their entrepreneurial goals.[12] According to a study about integrated literacy in rural Mali, developments in integrated literacy for Bambara speakers led to economic growth in Mali.[12]

Barriers

Amadou Sanogo, the leader of the 2012 coup d'état, citied the Malian education system as one of the reasons for his dissatisfaction with the Malian government.[7] Examples of problems with this education system include differences in vocabulary, an inability to access education, gender differences, and inefficiencies in education.[20][13][2][27][4][28][29] A few causes of these problems are geographic location, food and disease, and the poor quality of teaching.[8][16][15]

Language barriers

When Mali became independent from France, only 7% of Malians were literate in French.[19] A study by J.R. Hough revealed that the French language is a barrier to education in Mali since many people have not been exposed to this language, and most Malians speak local languages.[8][13] Neo-literates often have a difficult time utilizing their new skills since most publications and resources are in French.[10] Although Mali's first President, Modibo Keita, tried to utilize local languages, the government was still predominantly run in French.[19]

Access and regional differences

With gross primary enrollment and gross higher education enrollment increasing by factors of 2.75 and 16.7 respectively in two decades, Mali faces a severe shortage of teachers.[2] In addition to logistical issues, political issues have negatively affected educational enrollment rates.[27] Specifically following the Crisis of 2012, over half a million citizens were displaced from their primary locations of education.[27] Additionally, this led to an increase in food prices which further decreased the amount of money parents had to send their children to school.[29] Similarly, many parents cannot afford school prices due to high school fees or the contributions required by community schools.[1]

Geographic location is often cited as a cause of low enrollment rates.[1] In 2009, although Bamako, Mali's capital, had a 90% primary enrollment rate, this percentage was much lower in rural areas of Mali, where 7 in 10 Malians live.[1] About 7 in 100 primary students live over 5 kilometers from their institution of education.[1] Additionally, 1 in 12 schools have zero classrooms or just one classroom, and many of these classrooms suffer from poor infrastructure.[1] A study about food insecure Malian villages revealed that a fifth of schools in these areas are outside.[27]

Food and nutrition

The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations considers Mali a low income food deficit country.[27] In 2005, the World Food Programme classified 2 in 5 Malians as being food insecure or susceptible to food insecurity.[27] According to a 2013 study by Masset and Gelli which surveyed food insecure villages, food insecurity leads to fewer educational opportunities.[27] Food insecurity decreases interest in obtaining education and puts more of a focus on labor.[27] Consequently, these villages had lower attendance rates than the rest of the country.[27] 40% of children who were old enough to attend primary school actually enrolled in primary school, which is about 20% lower than the national average.[27] Additionally, a lack of proper nutrition can be detrimental to a child's brain formation.[15] When children do not get proper nutrition, their physical and cognitive development suffers.[15] This leads to lower levels of participation in educational systems and low levels of performance for those who do participate.[15]

Disability and disease

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 2 million Malians are considered disabled.[16] As of 2000, there were 200,000 people who were deaf in Mali.[8] A study by researcher and author Victoria Nyst revealed that meningitis and other diseases are main contributors to deafness, especially because Mali is a part of the African meningitis belt.[8] Most deaf Malians do not have access to formal education in sign language.[8] This is because there are no sign language classes for those who aren't deaf, leading to untrained teachers, interpreters, and parents.[8] This propagates a system in which the deaf population has less access to information about government initiatives such as major health campaigns.[8] In order to address this, the government has unsuccessfully tried to incorporate deaf students into hearing schools.[8] As an alternative, many deaf Malians are sent to other countries such as France and Russia.[8]

Malaria is also an issue which affects educational development.[15] In a 2010 study about the effects of malaria on the village of Diankabou, researchers found that malaria was responsible for the majority of deaths of children under 5 years old and over a third of all visits to health clinics.[15] Additionally, they found that malaria during pregnancy can negatively affect the development of a child.[15] Once a child is born, malaria can lead to speech delay and mental retardation for children under 5.[15] Thus, this disease is the main cause of students not attending class.[15] This study also revealed that malaria negatively influences educational and cognitive development.[15]

Gender disparities

Net enrollment rates and literacy rates are generally lower for girls compared to boys in Mali.[30] This disparity can be further magnified by geographic differences.[4] A 2012 survey discovered that 84.9% of women in rural areas who were surveyed had not formally completed any form of education.[31] Only 2.2% of all women surveyed, including those who lived in urban areas, had completed primary school.[31] A study about pastoralist schools in the Gao region of Northeast Mali revealed that the primary enrollment rate for girls was less than 60% which was approximately 20% lower than the primary enrollment rate of boys in that region.[4] Whereas both boys and girls in Gao suffer from living many kilometers away from school in communities with frequent droughts, girls must face gender bias in schooling and societal pressures to marry early and earn a high dowry through pursuing higher education.[4] The government perpetuated this system by forcing mainly pastoralist boys to go to boarding school.[4]

According to a study about rural Mali by Laurel Puchner, women often have a difficult time incorporating new literacy skills outside of the classroom, especially because they face discrimination in the areas of society that utilize neo-literate skills.[28][29] Additionally, many people, such as the researchers in this study, argue that students do not actually become literate through these programs due to inefficiencies in the implementation of literacy education.[28][29] For example, in the four villages where the Puchner study took place, many Malians were illiterate mainly because they endured poor learning conditions and had few print resources to become educated.[29]

Enrollment, completion, and dropout rates

In 2017, the primary net enrollment rate in Mali was 61%.[30] In terms of gender, 65% of boys and 58% of girls were enrolled in primary education.[30] However, the completion rate of primary education was 50% during the 2017 school year.[30] In the 1980s, these numbers were far more inefficient.[13] In fact, 1 in 7 students dropped out within the first three years of primary education, and 20,000 students were not able to successfully graduate to their second year of education.[13] These repetitions were not limited to a student's first year.[13] Considering students who dropout, the average length of time to complete a 9 year cycle of Malian education was 23 years.[13] These inconsistent, lengthy cycles led to lower enrollment rates.[13] For example, at one point, 1 in 10 Timbuktu children were attending school.[13] Despite these facts, Mali still faces a shortage of teachers.[13] In 2008, the trained teacher to student ratio was 1 to 105.[1] These issues can lead to illiteracy for adult populations.[30] In 2015, the adult literacy rate was 33%.[30] A 2013 study about Malian education revealed that citizens with lower education levels are more likely to turn to agriculture and migration rather than continuing to pursue education.[32]

Quality of teaching

In terms of the quality of education that Malian teachers have received, 1 in 3 primary education teachers have not completed their second cycle of education.[1] There have been initiatives such the Alternative Teaching Staff Recruitment Strategy or SARPE which tools teachers with 90 days of training, which many teachers cite as being too short in length.[1] Additionally, strikes related to wages are not uncommon.[1] For example, there was a strike by secondary teachers during the 2006 to 2007 school year related to the fact that teachers are paid on a monthly contractual basis with low wages.[1]

Initiatives

1962 Educational Reform Law

This law was passed right after Mali gained independence in an effort to improve the quality of Malian education and the accessibility of schooling.[2] This was part of a larger effort to decolonize Mali post independence and shift the French-focused curriculum towards incorporating more information about Africa.[2] This law introduced the Functional Literacy Program which provided education for adults who could not read or write in their local languages.[2] Additionally, this reform created the cyclical educational structure and specifically split Malian education into a 5 year cycle followed by a 4 year cycle.[17]

Other policies

The government continued to make changes to the Malian educational system in the 1960s.[17] In 1964, they created the National Pedagogic Institute made up of Malian, French, American, and UNESCO officials whose main purpose was to improve the Malian curriculum and textbooks.[17] However, this institute suffered from logistical inefficiencies and often didn't meet their original goals.[17] In addition to curriculum reform, the government initiated efforts to expand the number of schools. [17] By 1967, although there were 53 private schools, public schools were better able to compete with private education.[17] Towards the end of this decade, the government developed the existing structure of Malian education.[17] In 1968, the Ministry of National Education became a joint institution with the Ministry of Youth and Sports.[17] In 1969, the school cycle lengths were modified yet again to 6 years and 3 years, respectively.[17] Finally, in 1970, the government implemented the DEF, or Diploma d'Etudes Fondamental, which served as merit based exam to determine which students were able to transition to secondary and vocational schools following primary education.[17]

Policies in the 1990s

In 1992, the Malian government officially declared access to education as a constitutional right.[5] These views were part of a larger democratic movement that took place in Mali in the 1990s.[20] Consequently, seven years later, on December 29th, 1999, the Mali National Parliament passed the Education Act which created more educational opportunities for Malians.[2] During this decade, the government focused on non traditional education for adults and literacy.[5] Additionally, the government made more efforts to recruit and train teachers by giving primary educators two to four years of training.[17][1]

Ten Year Education Development Program

In 1998, the government passed the Ten Year Educational Development Plan as a way to make education universal, higher in quality, and more accessible.[2][1] Additionally, this plan was meant to reduce gender and geographic-based inequalities in education.[27] Also known as PRODEC or the Programme Décennal de Dévelopment de l'Education, this program made major developments in popularizing bilingual education and improving the quality of textbooks.[1] The government actually met their GER, or gross enrollment ration, goal by reaching a primary gross enrollment rate of 80% in 2008.[2][1]

Policies in the 2000s

The 2000s were defined by further improvements in Malian education, especially in terms of flexibility.[4] In addition to continuing to popularize bilingual education, the government allowed schools to complement core classes with community based classes.[4] After a 2002 study by Oxfam and the Institute for Popular Education revealed that educational resources are often difficult to access and convey gender biases, Oxfam developed a program to reduce educational gender discrimination and provide aid to low income families.[4] Researchers also advocated for more funding for adult education after discovering some of the inefficiencies in literacy programs for non traditional students.[5] Additionally, in 2009, the government implemented a nutritional program for underserved communities across Mali.[27]

Animatrices

Animatrices are local women and community leaders that make an effort to reduce gender bias in education.[4] These individuals generally have experience with social work and teach parents about the importance of equality in Malian education.[4] Additionally, they ensure that girls are regularly attending class and encourage any girls that drop out of school to return to class.[4] In a study about Gao, where animatrices are prominent, researchers found that the number of girls that attended schools nearly doubled in a three year span.[4]

Foreign aid

.jpg.webp)

Since 1987, Child Aid USA has been an organization that works to implement literacy programs for Malians and improve community education.[29] Similarly, USAID, is an organization that provides aid to 9 regions of Mali to improve early literacy programs and community education.[16] One major program that this organization developed was the Selective Integrated Reading Activity that helped over 300,000 Malians learn how to read.[16] Most recently, in 2018, USAID provided over 18 million US dollars in aid to Mali.[16] One other US based organization that helped Mali was the United States Department of Agriculture which promoted the McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program in Mali.[14] This three- part program provided more training to teachers which improved the reading abilities of students.[14] France and the World Bank are two other major donors to Mali.[1]

Disability policies

The Equitable Access to Education Program, Education Emergency Support Activity, and the Persons with Disabilities Project have each improved the quality of education for disabled Malians.[16] In terms of education for the deaf, the French version of American Sign Language, or ASL, and Malian Sign Language, which is also known as LSM, are the two main forms of sign language in Mali.[8] Although LSM utilizes local languages, which Malians are more familiar with, the United States supports ASL initiatives in Mali through working with the Peace Corps.[8] In contrast, the World Federation of the Deaf is one of the major organizations that advocates for LSM.[8] In 2007, the Endangered Language Documentation Program of the Hans Rausing Endangered Language Project created Project LSM which researched LSM and released their findings to the National Library in Mali.[8]

SAFE

In order to improve agricultural education, the Sasakawa-Global 2000 Institute created SAFE, or the Sasakawa Africa Fund for Extension Education.[33] This fund was incorporated into Mali in 2002 and has given Malians opportunities to obtain either a two year diploma or a Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Extension and Rural Development.[33] One major component of this program is the Supervised Enterprise Project which provides shadowing and internship opportunities for students and a chance for Malians to develop their agricultural opportunities through collaborating with farmer mentors and local universities.[33] For example, this program incorporates hundreds of hours of coursework and approximately 7 months of research.[33] Since 2002, over 150 professionals have graduated from this program or worked on a project, and 50 Malians received diplomas in 2007.[33]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Education in Mali. |

References

- "Delivering Education For All in Mali (Report) | Oxfam International". www.oxfam.org. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- Takyi-Amoako, Emefa; Diarra, Mohamed Chérif (2015-05-21). Education in West Africa. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. Ch. 18. ISBN 9781441177858.

- "Mali - History Background". education.stateuniversity.com. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- Aikman, Sheila; Unterhalter, Elaine (2005). Beyond Access: Transforming Policy and Practice for Gender Equality in Education. Oxfam. pp. 181–195. ISBN 9780855985295.

Mali.

- Gadio, Moussa (June 2011). "Policy Review on Adult Learning: The Adult Non-formal Education Policy of Mali, West Africa". Adult Learning. 22 (3): 20–24. doi:10.1177/104515951102200303. ISSN 1045-1595.

- Bleck, Jaimie (2015). Education and Empowered Citizenship in Mali. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 71–99. ISBN 9781421417820. OCLC 918941428.

- Bell, Dianna (2015). "Choosing Medersa: Discourses on Secular versus Islamic Education in Mali, West Africa". Africa Today. 61 (3): 45–63. doi:10.2979/africatoday.61.3.45. JSTOR 10.2979/africatoday.61.3.45. S2CID 141894424.

- Nyst, Victoria (2015). "The Sign Language Situation in Mali". Sign Language Studies. 15 (2): 126–150. ISSN 0302-1475. JSTOR 26190976.

- "Mali". uis.unesco.org. 2016-11-27. Retrieved 2019-10-08.

- Ouane, Adama; Amon-Tanoh, Yvette (December 1990). "Literacy in French-Speaking Africa: A Situational Analysis". African Studies Review. 33 (3): 21. doi:10.2307/524184. JSTOR 524184.

- Cisse, Seydou (2001). "Post Literacy in Mali". Journal AED - Adult Education and Development. 51.

- Turrittin, Jane (February 1989). "Integrated Literacy in Mali". Comparative Education Review. 33: 59–76. doi:10.1086/446812. S2CID 143699761.

- Hough, J. R. (1989). "Inefficiency in Education-The Case of Mali". Comparative Education. 25 (1): 77–85. doi:10.1080/0305006890250108. ISSN 0305-0068. JSTOR 3099004.

- Gulati, Kajal; Safarha, Elnaz, eds. (2019). The Impact of Food for Education Program on Literacy Improvement in Mali.

- Thuilliez, Josselin; d'Albis, Hippolyte; Niangaly, Hamidou; Doumbo, Ogobara (2017-08-01). "Malaria and Education: Evidence from Mali". Journal of African Economies. 26 (4): 443–469. doi:10.1093/jae/ejx004. ISSN 0963-8024.

- "Education Program Overview | Fact Sheet | Mali | U.S. Agency for International Development". www.usaid.gov. 2019-02-13. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- Obichere, Boniface I. (1976). "Politicians and Educational Reform in French-Speaking West-Africa: A Comparative Study of Mali and Ivory Coast". Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria. 8 (3): 55–68. ISSN 0018-2540. JSTOR 41971250.

- Cutter, Charles H. (1966). "Mali: A Bibliographical Introduction". African Studies Bulletin. 9 (3): 74–87. doi:10.2307/523253. JSTOR 523253.

- Bleck, Jaimie (2015). Education and Empowered Citizenship in Mali. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 24–55. ISBN 9781421417820. OCLC 918941428.

- Bleck, Jaimie (2015). Education and Empowered Citizenship in Mali. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1–23. ISBN 9781421417820. OCLC 918941428.

- "Mali". uis.unesco.org. 2016-11-27. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- Ministry of Education Archived 2009-02-04 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2009-02-10

- Ministre de L’Education de Base, de L’Alphabétisation et des Langues Nationales Archived 2008-12-30 at the Wayback Machine.Retrieved 2009-02-10

- Ministre des Enseignements Secondaire, supérieur et de la Recherche scientifique Archived 2009-03-12 at the Wayback Machine.Retrieved 2009-02-10

- MALI: Students left behind in race for education MDG. IRIN/United Nations. 6 February 2009.

- University of Bamako Archived 2009-01-29 at the Wayback Machine. retrieved 2009-02-10.

- Gelli, Aulo; Masset, Edoardo; Diallo, Amadou Sekou; Assima, Amidou; Hombrados, Jorge; Watkins, Kristie; Drake, Lesley (2014-11-01). "Agriculture, nutrition and education: On the status and determinants of primary schooling in rural Mali before the crises of 2012". International Journal of Educational Development. 39: 205–215. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.07.003. ISSN 0738-0593.

- Puchner, Laurel (2001). "Researching Women's Literacy in Mali: A Case Study of Dialogue among Researchers, Practitioners, and Policy Makers". Comparative Education Review. 45 (2): 242–256. doi:10.1086/447663. ISSN 0010-4086. S2CID 141820908.

- Puchner, L. (2003-07-01). "Women and literacy in rural Mali: a study of the socio-economic impact of participating in literacy programs in four villages". International Journal of Educational Development. 23 (4): 439–458. doi:10.1016/S0738-0593(03)00015-4. ISSN 0738-0593.

- "Education Statistics". datatopics.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- "Mali 2012–13". Studies in Family Planning. 46 (2): 227–236. 2015. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2015.00026.x. ISSN 0039-3665. JSTOR 24642182. PMID 26059992.

- van der Land, Victoria; Hummel, Diana (2013). "Vulnerability and the Role of Education in Environmentally Induced Migration in Mali and Senegal". Ecology and Society. 18 (4). ISSN 1708-3087. JSTOR 26269395.

- Kante, Assa, Edwards, Craig, Blackwell, Cindy, Henneberry, Shida and Key, James (2010). An assessment of the Sasakawa Africa Fund for Extension Education's (SAFE) training program in Mali: Graduates' perceptions of the training's impact as well as opportunities and constraints related to Supervised Enterprise Projects (SEPs) (Dissertation/Thesis). Retrieved 2019-10-20 – via ProQuest.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)