Edward Bernard

Edward Bernard (1638 – 12 January 1697) was an English scholar and Savilian professor of astronomy at the University of Oxford, from 1673 to 1691.[1]

Life

He was born at Paulerspury, Northamptonshire.[2] He was educated at Merchant Taylors' School and St John's College, Oxford, where he was a scholar in 1655; he became a Fellow in 1658, and graduated M.A. in 1662.[1][3]

He began to teach astronomy as deputy to Christopher Wren, then Savilian professor. This was from 1669, the year in which Wren became Surveyor-General of the King's Works. Eventually Wren was too busy, and resigned the chair.[4]

In 1673 he became Savilian professor, Fellow of the Royal Society, and chaplain to Peter Mews. In 1676 he went to Paris, as tutor to Henry FitzRoy, 1st Duke of Grafton and George FitzRoy, 1st Duke of Northumberland.[1] From the 1670s he built up good contacts with European scholars. He corresponded with Hiob Ludolf, and met his nephew Heinrich Wilhelm Ludolf in Oxford.[5] He visited Pierre-Daniel Huet,[6] and corresponded with Jean Mabillon and Pasquier Quesnel.[7]

He observed the comet of 1680 and corresponded about it with John Flamsteed.[8] In 1691 he became rector of Brightwell in Oxfordshire.[9]

His biography was written by his friend Thomas Smith.[10][11]

He died in Oxford on 12 January 1697, and was buried four days later in St John's College chapel.[1]

Works

He spent much time on manuscripts of Apollonius of Perga, travelling to Leiden to look at the manuscript legacies of Joseph Scaliger and Levinus Warner in 1669, and working on Arabic texts in the Bodleian Library.[3][13][14][15] He returned to the Netherlands more than two decades later, to purchase at auction items from the library of Jacobus Golius, on behalf of Narcissus Marsh.[16] In parallel, he began to edit the works of Josephus in the 1680s. The geometrical work remained fragmentary, while the Josephus edition was heavily annotated but incomplete.[17] Clement Barksdale circulated some doggerel about it: "Savilian Bernard's a right learned man;/Josephus he will finish when he can."[18] His transcriptions and translations were later used by Edmund Halley in his translation of Apollonius.[19]

Much of Bernard's scholarly work remained as book annotations, and came back to the Bodleian when it purchased those books from his library after his death.

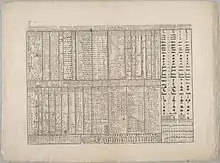

De mensuris et ponderibus antiquis (1688), on ancient weights and measures, first was an appendix to a work of Edward Pococke,[20] and then published separately in an expanded version.[21] With Humphrey Hody and Henry Aldrich he issued an edition of Aristeas.[22] The Orbis Eruditi was a table of many alphabets.[23]

His Catalogi librorum manuscriptorum Angliae et Hiberniae in unum collecti cum indice alphabetico (Oxford, 1697), colloquially "Bernard's Catalogue", was a catalogue of manuscripts in British and Irish libraries, and served as a major tool for scholars. Humfrey Wanley assisted him with this compilation.[24]

Recent sources claim that his assertion that tenth-century Egyptian astronomer Ibn Yunis used a pendulum for time measurement, predating Galileo, has no basis in fact.[25][26]

References

- Sowerby, E. M. Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, 1952, v. 1, p. 4

Notes

- Clerke, Agnes Mary (1922). "Bernard, Edward". In Smith, George (ed.). Concise Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. pp. 378–80.

- "Northamptonshire: County Survey". Society for the History of Astronomy. Archived from the original on 14 March 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Mordechai Feingold, Oriental Studies, p. 491 in Trevor Henry Aston, Nicholas Tyacke (editors), The History of the University of Oxford: Volume IV: Seventeenth-Century Oxford(1984).

- Campbell, James W. P. (October 2000). "Christopher Wren: Architectural Career". Archived from the original on 27 August 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Okabe, Shoichi (25 February 1985). "Russian grammars before Lomonosov". Kanazawa University Repository for Academic resources. pp. 129–130. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Memoirs of the life of Peter Daniel Huet, Bishop of Avranches, written by himself (1810), translation by John Aikin, vol. II, p. 188.

- Schmitz du Moulm H. , Un correspondant anglais de Quesnel: Lettres de Q à Edward Bernard, professeur d'astronomie à Oxford, Lias, 2 (1975), 281–312.

- Mordechai Feingold, Mathematical Sciences and New Philosophies, p. 384 in Trevor Henry Aston, Nicholas Tyacke (editors), The History of the University of Oxford: Volume IV: Seventeenth-Century Oxford(1984).

- "Parishes: Brightwell", in A History of the County of Berkshire: Volume 3, ed. P. H. Ditchfield and William Page (London, 1923), pp. 464-471. British History Online. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Smith, Thomas (1704) Vita clarissimi & doctissimi viri, Edwardi Bernardi (in Latin). London: A. & J. Churchill

- Joseph M. Levine, The Battle of the Books: History and Literature in the Augustan Age (1994), p. 69.

- Edwin JEANS (1860). A Catalogue of Books, in all Branches of Literature, both Ancient & Modern ... on sale at E. Jeans's, bookseller ... Norwich. J. Fletcher. pp. 33–.

- "Some notes about books in the publick Library of Oxon.; Queen M.['s] death; Dr Wallis's eyes; Dr Busby's Algebra". Archived from the original on 3 January 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "David Gregory Papers". Edinburgh University Library Special Collections Division. Archived from the original on 22 February 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 March 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Twells, Leonard, et al. (1816). The Lives of Dr. Edward Pocock, the celebrated orientalist, Vol. 1, pp. 291-2. Vol. 2

- Flavii Josephi Antiquitatum Judaicarum libri quatuor priores, et pars magna quinti

- Mentioned in Camden Society Publications 23, 1838.

- M.B. Hall, 'Arabick Learning in the Correspondence of the Royal Society, 1660–1677', The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in 17th-Century England, p.154

- Pococke, Edward. A commentary on the prophecy of Hosea. Oxford: printed at the Theater (1685)

- Stecchini, Livio C. "The Derivation of European Units". A History of Measures. Metrum.org. Accessed 5 January 2019.

- Aristeae historia LXXII, about 1692.

- Orbis eruditi literatura à charactere Samaritico deducta (Oxford, 1689).

- "The Cottonian and the Harleian Libraries". The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21). Volume IX, Ch. 13, §30.

- O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. (November 1999). "Abu'l-Hasan Ali ibn Abd al-Rahman ibn Yunus". University of St Andrews. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- King, D. A. (1979). "Ibn Yunus and the pendulum: a history of errors". Archives Internationales d'Histoire des Sciences. 29 (104): 35–52. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2019.