Edward Lhuyd

Edward Lhuyd (pronounced [ˈɬʊid]; occasionally written Llwyd in line with Modern Welsh orthography, 1660 – 30 June 1709) was a Welsh naturalist, botanist, linguist, geographer and antiquary. He is also known by the Latinized form of his name: Eduardus Luidius.

Life

Lhuyd was born in 1660, in Loppington, Shropshire, the illegitimate son of Edward Lloyd of Llanforda, Oswestry, and Bridget Pryse of Llansantffraid, near Talybont, Cardiganshire in 1660. He attended and later taught at Oswestry Grammar School. His family belonged to the gentry of south-west Wales. Though well-established, the family was not wealthy. His father experimented with agriculture and industry in a manner that impinged on the new science of the day. Lhuyd attended grammar school in Oswestry and went up to Jesus College, Oxford in 1682, but dropped out before graduation. In 1684, he was appointed to assist Robert Plot, Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum and replaced him as such in 1690, holding the post until his death in 1709.[1]

While at the Ashmolean, he travelled extensively. A visit to Snowdonia in 1688 allowed him to compile for John Ray's Synopsis Methodica Stirpium Britannicorum a list of flora local to that region. After 1697, Lhuyd visited every county in Wales, then travelled to Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall, Brittany and the Isle of Man. In 1699, funding from his friend Isaac Newton allowed him to publish Lithophylacii Britannici Ichnographia, a catalogue of fossils collected in England, mostly in Oxford, and now held in the Ashmolean.

In 1701, Lhuyd received a MA honoris causa from the University of Oxford, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1708.[1]

Lhuyd was responsible for the first scientific description and naming of what we would now recognize as a dinosaur: the sauropod tooth Rutellum implicatum (Delair and Sarjeant, 2002).

Pioneering linguist

In the late 17th century, Lhuyd was contacted by a group of scholars led by John Keigwin of Mousehole, who sought to preserve and further the Cornish language. He accepted their invitation to travel there to study it. Early Modern Cornish was the subject of a paper published by Lhuyd in 1702; it differs from the medieval language in having a considerably simpler structure and grammar.

In 1707, having been assisted in his research by fellow Welsh scholar Moses Williams, he published the first volume of Archaeologia Britannica: an Account of the Languages, Histories and Customs of Great Britain, from Travels through Wales, Cornwall, Bas-Bretagne, Ireland and Scotland. This has an important linguistic description of Cornish, noted all the more for its understanding of historical linguistics. Some of the ideas commonly attributed to linguists of the 19th century have their roots in this work by Lhuyd, who was "considerably more sophisticated in his methods and perceptions than [Sir William] Jones".[2]

Lhuyd noted the similarity between the two linguistic families: Brythonic or P–Celtic (Breton, Cornish and Welsh); and Goidelic or Q–Celtic (Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic). He argued that the Brythonic languages originated in Gaul (France), and the Goidelic languages in the Iberian Peninsula. He concluded that as the languages were of Celtic origin, the people who spoke them were Celts. From the 18th century, the peoples of Brittany, Cornwall, Ireland, Isle of Man, Scotland and Wales were known increasingly as Celts, and are seen to this day as modern Celtic nations.[3][4]

Death and legacy

During his travels, Lhuyd developed asthma, which eventually led to his death from pleurisy in Oxford in 1709.[1]

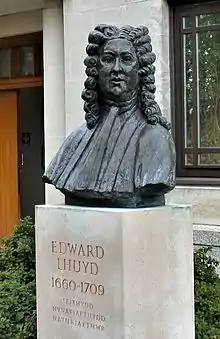

The Snowdon lily (Gagea serotina) was for a time called Lloydia serotina after Lhuyd. Cymdeithas Edward Llwyd, the National Naturalists' Society of Wales, is named after him. On 9 June 2001 a bronze bust of him was unveiled by Dafydd Wigley, former Plaid Cymru leader, outside the University of Wales's Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies in Aberystwyth, next to the National Library of Wales. The sculptor was John Meirion Morris; the plinth, carved by Ieuan Rees, reads EDWARD/LHUYD/1660–1709/IEITHYDD/HYNAFIAETHYDD/NATURIAETHWR ("linguist, antiquary, naturalist").[5]

Further reading

- Justin B. Delair and William A. S. Sarjeant, "The earliest discoveries of dinosaurs: the records re-examined", Proceedings of the Geologists' Association 113, 2002, 185–197

- Frank Emery, Edward Lhuyd, 1971

- Dewi W. Evans and Brynley F. Roberts, eds, Archæologia Britannica: Texts and Translations, Celtic Studies Publications 10, 2007 Description

- R. T. Gunther, The Life and Letters of Edward Lhuyd, 1945

- Brynley F. Roberts, Edward Lhuyd, the Making of a Scientist, 1980

- Derek R. Williams, Prying into every hole and corner: Edward Lhuyd in Cornwall in 1700, 1993

- Derek R. Williams, Edward Lhuyd, 1660–1709: A Shropshire Welshman, 2009

- Never at rest, A biography of Isaac Newton by Richard S. Westfall ISBN 0521274354 581 pp.

References

- Thomas Jones. "Lhuyd, Edward (1660–1709), botanist, geologist, antiquary and philologist". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Campbell, Lyle, and William J. Poser (2007). Language Classification. History and Method. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-521-88005-3.

- Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. p. 54. ISBN 0-14-014581-8.

- "Who were the Celts? ... Rhagor". Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales website. Amgueddfa Cymru– National Museum Wales. 4 May 2007. Archived from the original on 17 September 2009. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- "Edward Lhuyd Memorial", National Recording Project, Public Monuments and Sculpture Association, archived from the original on 13 May 2016, retrieved 30 June 2016

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Lhuyd. |

- Archaeologia Britannica (1707). Downloadable pdf at The Internet Archive

- Biography of Edward Lhuyd from the Canolfan Edward Llwyd, a centre for the study of science through Welsh

- Lithophylacii Britannici ichnographia (1699) – full digital facsimile from Linda Hall Library