Emanuel Bronner

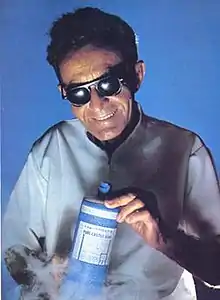

Emanuel Theodore Bronner (![]() Emanuel Heilbronner ,[2] born February 1, 1908 – March 7, 1997) was the maker of Dr. Bronner's Magic Soaps.[3] He used product labels to promote his moral and religious ideas, including a belief in the goodness and unity of humanity.

Emanuel Heilbronner ,[2] born February 1, 1908 – March 7, 1997) was the maker of Dr. Bronner's Magic Soaps.[3] He used product labels to promote his moral and religious ideas, including a belief in the goodness and unity of humanity.

Emanuel Bronner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Emanuel Theodor Heilbronner February 1, 1908 |

| Died | March 7, 1997 (aged 89) |

| Nationality | German-American |

| Occupation | Soap maker, entrepreneur, philosopher |

| Known for | Dr. Bronner's Magic Soaps |

History

Bronner was born in Heilbronn, Germany, to the Heilbronner family of soap makers.[4] He emigrated to the United States in 1929, dropping "Heil" from his name because of its associations with Nazism.[5] He became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1936.[5] As the family was Jewish, he pleaded with his parents to emigrate with him for fear of the then-ascendant Nazi Party, but they refused. His last contact with his parents was in the form of a censored postcard saying, "You were right. —Your loving father."[6] His parents were murdered in the Holocaust.

Bronner's 1936 naturalization certificate making him a U.S. citizen

Bronner's 1936 naturalization certificate making him a U.S. citizen Portrait from the naturalization certificate

Portrait from the naturalization certificate

Career

He started his business making products such as castile soap by hand in his home. The product labels are crowded with statements of Bronner's philosophy, which he called "All-One-God-Faith" and the "Moral ABC",[7] both of which he included on the label of every soap bottle he produced.[8] Many of Bronner's references came from Jewish and Christian sources, such as the Shema and the Beatitudes; others from writers such as Rudyard Kipling and Thomas Paine. On his labels, he referred to the Jewish sage Hillel the Elder as "Rabbi Hillel" and to Jesus Christ as "Rabbi Jesus."[9] The labels became famous for their idiosyncratic style, including hyphens to join long strings of words and the liberal use of exclamation marks.[10]

In 1946, while promoting his "Moral ABC" at the University of Chicago, Bronner was arrested for refusing to leave the dean's office, despite the fact he was invited to the campus to lecture by a local student group, and then committed to the Elgin Mental Health Center, a mental hospital in Elgin, Illinois, from which he escaped after shock treatments. Bronner believed those shock treatments brought about his eventual blindness.[2]

After moving his family several times, he settled in Escondido, California, where eventually his soap-making operation grew into a small factory. At his death in 1997, it produced more than a million bottles of soap and other products per year, but was still not mechanized.[11] The firm has been the subject of many published articles and has supported many charitable causes.[11]

Legacy

After Bronner's death, his family has continued to run the business. His grandson David Bronner is currently CEO.[12][13]

His life was the subject of a 2007 documentary film, Dr. Bronner's Magic Soapbox, which premiered on the Sundance TV channel, on 3 July 2007.[8][14][15]

The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society has a ship, the MV Emanuel Bronner, donated by the soap company.[16]

References

- Green, David B. (March 7, 2013). "This Day in Jewish History 1997: Creator of Dr. Bronner's "Magic" Moral Soaps Dies". Haaretz. Archived from the original on February 23, 2018.

- "On his soapbox: Man of ideas lathered his cleansing product with messages". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. June 8, 1997. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- Bryony Gomez Palacio, Armin Vit (2011). Graphic Design Referenced: A Visual Guide to the Language, Applications, and History of Graphic Design. Rockport Publishers. p. 311. ISBN 978-1592537426.

- "Dr. Bronner's Soap".

- Lubinski, Christina; Menniken, Marvin (October 25, 2013). Wadhwani, R. Daniel (ed.). "Emanuel Bronner". Immigrant Entrepreneurship: German-American Business Biographies, 1720 to the Present. German Historical Institute. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- "Why the weird religious ravings on Dr. Bronner's soap?". The Straight Dope. April 22, 1988. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- Foster, Tom (April 3, 2012). "The Undiluted Genius of Dr. Bronner's". Inc.com. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- Ben Ehrlich, Dr. Bronner's Soapy History, The [Jewish] Forward, June 29, 2007, page 2.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original on December 19, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) "The Moral ABC [Parts] I & II" by Dr. Emmanuel Bronner. Page 23: "Rabbi Hillel taught Jesus to unite the whole human race in our Eternal Father's great, All-One-God-Faith." Page 36: "A Human being must teach friend & Enemy the Moral ABC uniting all mankind free or that being is not yet human! Rabbi Jesus' full truth No. 1." Page 39: "To stay free: Small minds discuss people. Average minds discuss events. Great minds teach Rabbi Hillel's Moral ABC."

- Philpott, Tom (October 20, 2014). "Why Did Top Scientific Journals Reject This Dr. Bronner's Ad?". Mother Jones. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

-

Gail Grenier Sweet (January 2001). ""Next To Godliness: The Story Behind Dr. Bronner's Soap," an interview with Ralph Bronner". The Sun. Archived from the original on May 8, 2001. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

2 million bottles are packed by hand ... Four to five people, not working fast, pack them with no machines

- Harkinson, Josh (May 24, 2014). "How Dr. Bronner's Soap Turned Activism Into Good Clean Fun". Mother Jones. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- Leson, Gero. "Applying Fair Trade Principles To A Manufacturing Supply Chain (presentation by Gero Leson, Dr. Bronner's Magic Soaps Director of Special Operations)" (PDF). World Fair Trade Organization. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- Catsoulis, Jeannette (June 29, 2007). "Movie Review - Dr. Bronner's Magic Soapbox: Beneath the Bubbles". The New York Times.

- McClelland, Mac (2007). "Dr. Bronner's Magic Soapbox". Mother Jones (November/December). Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- "Introducing the latest addition to the Sea Shepherd fleet, the M/V Emanuel Bronner". Sea Shepherd. June 2, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.