Beatitudes

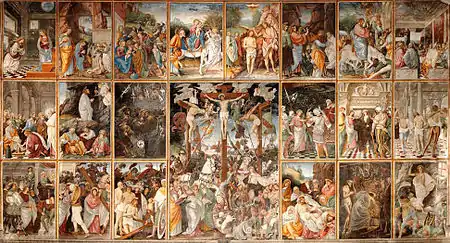

The Beatitudes are eight blessings recounted by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount in the Gospel of Matthew. Each is a proverb-like proclamation, without narrative. Four of the blessings also appear in the Sermon on the Plain in the Gospel of Luke, followed by four woes which mirror the blessings.[1]

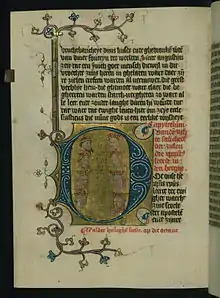

In the Vulgate, each of these blessings begins with the word beati, which translates to "happy", "rich", or "blessed" (plural adjective). The corresponding word in the original Greek is μακάριοι (makarioi), with the same meanings.[lower-alpha 1][3] Thus "Blessed are the poor in spirit" appears in Latin as beati pauperes spiritu.[4] The Latin noun beātitūdō was coined by Cicero to describe a state of blessedness. Later incorporated within the chapter headings written for Matthew 5 in various printed versions of the Vulgate.[5] Subsequently, the word was anglicized to beatytudes in the Great Bible of 1540,[6] and has, over time, taken on a preferred spelling of beatitudes.

Biblical basis

While opinions may vary as to exactly how many distinct statements into which the Beatitudes should be divided (ranging from eight to ten), most scholars consider them to be only eight.[7][8] These eight of Matthew follow a simple pattern: Jesus names a group of people normally thought to be unfortunate and pronounces them blessed.[1]

Matthew 5:3–12

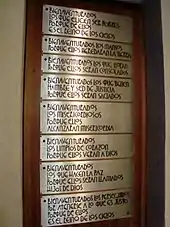

The eight Beatitudes in Matthew:[7][8][9]

3Blessed are the poor in spirit,

for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.

4Blessed are those who mourn,

for they will be comforted.

5Blessed are the meek,

for they will inherit the Earth.

6Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness,

for they will be satisfied.

7Blessed are the merciful,

for they will be shown mercy.

8Blessed are the pure in heart,

for they will see God.

9Blessed are the peacemakers,

for they will be called children of God.

10Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness,

for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.

11Blessed are you when people insult you, persecute you and falsely say all kinds of evil against you because of me.

12Rejoice and be glad, because great is your reward in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you.

The ninth beatitude (Matthew 5:11–12) refers to the bearing of reviling and is addressed to the disciples.[10][11] R. T. France considers verses 11 and 12 to be based on Isaiah 51:7.[12]

The Beatitudes unique to Matthew are the meek, the merciful, the pure of heart, and the peacemakers, while the other four have similar entries in Luke, but are followed almost immediately by "four woes".[13] The term "poor in spirit" is unique to Matthew. While thematically similar the introduction of the phrase "Poor in spirit" spiritualizes or ethicizes the poor in their predicament (in alignment with Isaiah 61)[14] while the Lucan version focuses on their actual hardship, poverty, marginalization and rejection of the poor who will see eventual vindication.

Luke

The four Beatitudes in Luke 6:20–22 are set within the Sermon on the Plain.

20Looking at his disciples, he said:

"Blessed are you who are poor,

for yours is the kingdom of God.

21Blessed are you who hunger now,

for you will be satisfied.

Blessed are you who weep now,

for you will laugh.

22Blessed are you when people hate you,

when they exclude you and insult you

and reject your name as evil,

because of the Son of Man.

Luke 6:23 ("Rejoice in that day and leap for joy, because great is your reward in heaven. For that is how their ancestors treated the prophets.") appears to parallel the text in Matthew 5:11–12.

The four woes that follow in Luke 6:24–26[15][7]

24"But woe to you who are rich,

for you have already received your comfort.

25Woe to you who are well fed now,

for you will go hungry.

Woe to you who laugh now,

for you will mourn and weep.

26Woe to you when everyone speaks well of you,

for that is how their ancestors treated the false prophets.

These woes are distinct from the Seven Woes of the Pharisees which appear later in Luke 11:37–54.

Analysis and interpretation

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

Each Beatitude consists of two phrases: the condition and the result. In almost all cases the phrases used are familiar from an Old Testament context, but in the Sermon on the Mount Jesus elevates them to new levels and teachings. Together, the Beatitudes present a new set of ideals that focus on love and humility rather than force and exaction. They echo the highest ideals of Jesus' teachings on spirituality and compassion.[13]

The term "the meek" would be familiar in the Old Testament, e.g., as in Psalm 37:11.[16] Although the Beatitude concerning the meek has been much praised even by some non-Christians such as Mahatma Gandhi, some view the admonition to meekness skeptically. Friedrich Nietzsche in On the Genealogy of Morals considered the verse to be embodying what he perceived as a slave morality.[17]

In Christian teachings, the Works of Mercy, which have corporal and spiritual components, have resonated with the theme of the Beatitude for mercy.[18] These teachings emphasize that these acts of mercy provide both temporal and spiritual benefits.[1][8] The theme of mercy has continued in devotions such as the Divine Mercy in the 20th century.[19]

The term "peacemakers" has traditionally been interpreted to mean not only those who live in peace with others, but also those who do their best to promote friendship among mankind and between God and man. St. Gregory of Nyssa interpreted it as "Godly work", which was an imitation of God's love of man.[8][18] John Wesley said the peacemakers 'endeavour to calm the stormy spirits of men, to quiet their turbulent passions, to soften the minds of contending parties, and, if possible, reconcile them to each other. They use all innocent arts, and employ all their strength, all the talents which God has given them, as well to preserve peace where it is, as to restore it where it is not.'[20]

The phrase "poor in spirit" (πτωχοὶ τῷ πνεύματι) in Matthew 5:3 has been subject to a variety of interpretations. A.W. Tozer describes poverty of spirit as "an inward state paralleling the outward circumstances of the common beggar in the streets." It is not a call to material poverty in itself.

These blessed poor are no longer slaves to the tyranny of things. They have broken the yoke of the oppressor; and this they have done not by fighting but by surrendering. Though free from all sense of possessing, they yet possess all things. "Theirs is the kingdom of heaven."[21]

William Burnet Wright, seeking to avoid a common misunderstanding of the meaning of poverty of spirit, distinguishes those who are "poor in spirit" from those he calls "poor spirited," who "consider crawling the Christian's proper gait."

There are men who fear to call their souls their own, and if they did, they would deceive—themselves. At times such men baptize their cowardice in holy water, name it humility, and tremble. ...They are not blessed. Their life is a creeping paralysis. Afraid to stand for their convictions, they end by having no convictions to stand to.[22]

In other religious texts

In the Book of Mormon, a religious text of the Latter Day Saint movement, Jesus gives a sermon to a group of indigenous Americans including statements very similar to Matthew 6 and evidently derived therefrom:[23]

Yea, blessed are the poor in spirit 'who come unto me,' for theirs is the kingdom of heaven (3 Nephi 12:3).[24]

And blessed are all they who do hunger and thirst after righteousness, for they shall be filled 'with the Holy Ghost' (3 Nephi 12:6).[24]

The Baháʼí Lawḥ-i-Aqdas tablet contains the statement:

Blessed the soul that hath been raised to life through My quickening breath and hath gained admittance into My heavenly Kingdom.[25]

The Qur'an quotes the Bible only in Q:21:105 which resembles Psalm 25:13 referred to in Matthew 5:5; but the Qur'an uses "righteous" rather than "meek".[26] The Qur'an (e.g., "say the word of humility and enter the gate of paradise") and some Hadith (e.g., "My mercy exceeds my anger") contain some passages with somewhat similar tone, but distinct phraseology, from the Beatitudes.[27]

The Bhagavad Gita and the traditional writings of Buddhism (e.g., some of the Mangala Sutta) have been interpreted as including teachings whose intentions resemble some of the messages of Beatitudes (e.g., humility and absence of ego), although their wording is not the same.[27][28]

Six "modern Beatitudes" were proposed by Pope Francis during his visit to Malmö, Sweden on All Saints Day 2016:[29]

- Blessed are those who remain faithful while enduring evils inflicted on them by others and forgive them from their heart

- Blessed are those who look into the eyes of the abandoned and marginalized and show them their closeness

- Blessed are those who see God in every person and strive to make others also discover Him

- Blessed are those who protect and care for our common home

- Blessed are those who renounce their own comfort in order to help others

- Blessed are those who pray and work for full communion between Christians.

See also

Notes

- "[T]he name of "Makaria", the "blessed" or "prosperous" one— ...as well as the family's membership in the upper classes.[2]

References

- Majerník, Ján; Ponessa, Joseph; Manhardt, Laurie Watson (2005). The Synoptics: Matthew, Mark, Luke. Steubenville, OH: Emmaus Road. pp. 63–68. ISBN 1-931018-31-6.

- Roselli, David Kawalko (April 2007), "Gender, Class and Ideology: The Social Function of Virgin Sacrifice in Euripides' Children of Herakles", Classical Antiquity, University of California Press, 26 (1): 81–169, doi:10.1525/ca.2007.26.1.81.

- Liddell; Scott, Lexicon,

Blessed, happy, fortunate; in Attic, one of the upper classes.

- The Vulgate New Testament with the Douay Version of 1582 in Parallel Columns. p. 5.

- Savage, Henry Edwin (1910). The Gospel of the Kingdom. p. 69.

- Great Bible. 1540. p. 431.

- Aune, David Edward (2003). The Westminster Dictionary of New Testament and early Christian literature. pp. 75–78. ISBN 978-0-664-21917-8.

- Beatitudes. Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- Matthew 5:3–12

- Hunsinger, George (March 2016), The Beatitudes, Paulist Press.

- Vost, Kevin (2006), The Nine Beatitudes, Memorize the Faith, NH: Sophia Institute Press, p. 553.

- France, R.T. (October 1987). The Gospel According to Matthew: an Introduction and Commentary (1 ed.). Leicester: Send the Light. ISBN 0-8028-0063-7.

- Plummer, Rev. Arthur (for entry "Beatitudes") (1898). Hastings, James; Selbie, John A; Davidson, A B; Driver, S R; Swete, Henry Barclay (eds.). Volume I: A–Feasts. Dictionary of the Bible: dealing with its language, literature, and contents, including the Biblical theology. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. pp. 261–262. ISBN 1410217221 – via Google Books.

- The Oxford Companion to the Bible, Ed. Metzger and Coogan, 1993 p. 688 ISBN 0-19-504645-5

- Luke 6:24–26

- Hill, David (June 1981). Gospel of Matthew. New Century Bible Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-1886-2.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich (1999) [1887]. On the Genealogy of Morals [Zur Genealogie der Moral] (PDF). USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19283617-5.

- Jegen, Carol Frances (1986). Jesus the Peacemaker. Kansas City, MO: Sheed & Ward. pp. 68–71. ISBN 0-934134-36-7.

- Torretto, Richard (2010). A Divine Mercy Resource. New York: iUniverse. pp. 53, 126. ISBN 978-1-4502-3236-4.

- Wesley, J., 'Upon Our Lord's Sermon On The Mount: Discourse Three', Sermon 23, accessed 11 October 2015

- A.W. Tozer (1957), The Pursuit of God.

- William Burnet Wright, Master and Men (1894), pp. 39–40

- Ridges, David (2007). The Book of Mormon Made Easier, Part III. Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort. pp. 148–49. ISBN 978-1-55517-787-4.

- "Third Nephi, Chapter 12". The Book of Nephi. Church of Christ (Latter Day Saints). 3: 3. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- Bahá'u'lláh (1988). Tablets of Bahá'u'lláh Revealed After the Kitáb-i-Aqdas (pocket-size ed.). US Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 269. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- Akhtar, Shabbir (December 19, 2007). The Quran and the Secular Mind. London, New York: Routledge. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-41543783-7.

- Randall, Albert B. (2006). Strangers on the Shore: The Beatitudes in World Religions. pp. 41–44. ISBN 978-0-8204-8136-4.

- Spiro, Melford E. (May 27, 1982). Buddhism and Society. p. 359. ISBN 0-52004672-2.

- "Pope offers new Beatitudes for saints of a new age". Catholic news. 2016.

Bibliography

- Easwaran, Eknath. Original Goodness (on Beatitudes). Nilgiri Press, 1989. ISBN 0-915132-91-5.

- Kissinger, Warren S. The Sermon on the Mount: A History of Interpretation and Bibliography. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press, 1975.

- Twomey, M.W. "The Beatitudes". A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. Jeffrey, David Lyle ed. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans, 1992.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Beatitudes |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beatitudes. |

Beatitudes | ||

| Preceded by First disciples of Jesus |

Gospel harmony Events |

Succeeded by The Antitheses in the Sermon on the Mount |