Emergency Fighter Program

The Emergency Fighter Program (German: Jägernotprogramm) was the program that resulted from a decision taken on July 3, 1944 by the Luftwaffe regarding the German aircraft manufacturing companies during the last year of the Third Reich.

This project was one of the products of the latter part of 1944, when the Luftwaffe High Command saw that there was a dire need for a strong defense against Allied bombing raids. Although opposed by important figures such as Luftwaffe fighter force leader Adolf Galland, the project went ahead owing to the backing of Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring.[1] Most of the designs of the Emergency Fighter Program never proceeded past the project stage.[2]

History

1944 opened with massive bombing raids by the US Army Air Force and RAF Bomber Command on a scale not seen before. With a shift of emphasis from targeting strategic targets to the destruction of the Luftwaffe, during the Big Week in late February 1944 the Luftwaffe fighter force was broken. Attempts to address this failed, and by the summer, Allied planes were roaming at will over most of Germany.

Jet fighters like the Messerschmitt Me 262, at that time about to enter service, had a clear performance advantage over the Allied aircraft but were expensive and difficult to keep operational. This led to the idea of a much less expensive design that could be easily built and so inexpensive that any extensive problems would be addressed by simply disposing of the aircraft. This became the genesis of the Emergency Fighter Program as part of shifting production to defensive interceptor/fighters. A number of new aircraft design competition programmes were launched to provide new jet fighters.

Production of the Messerschmitt Me 262A fighter versions continued, as well as the development of advanced piston-engined fighters such as the Dornier Do 335 as per Hitler's personal request on May 23, 1944, before the July 3 announcement of the program. Bomber designs powered by piston engines were severely curtailed or outright cancelled, with only jet bombers allowed to continue in production, such as the Arado Ar 234. New jet bombers such as the Junkers Ju 287 and Heinkel He 343 were worked on fitfully as low priority projects in the last months of the war.

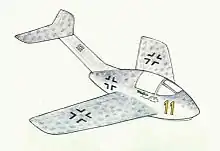

Towards the end of the war in the design of the planes little thought was given to the safety or comfort of the pilots who were mostly Hitler Youth motivated by fanaticism. Some of the fighters, such as the Heinkel P.1077 Julia, the Blohm & Voss BV 40 and the Arado E.381 Kleinstjäger – "smallest fighter" were designed with the pilot flying the aircraft in a prone position. Powered by rockets, certain designs were a blend of "aircraft and projectile" in the words of Nazi propaganda, with a vertical takeoff like a missile launch system attempted for the first time in a manned aircraft, such as the Bachem Ba 349 Natter —in which the test-pilot died in the first flight.[3] The Natter and Julia designs were expected to climb to their ceiling at vertical or near vertical angles, while the Arado design was a parasite aircraft that needed to be carried by a "mother" plane, with the unpowered BV 40 needing an aerotow into action.

These small interceptors had fuel for only a few minutes for combat action and landing was fraught with hazards, for after spending the rocket fuel the center of gravity would shift substantially making the aircraft difficult to handle at best and uncontrollable at worst. In the Natter or in the Fliegende Panzerfaust the pilot had to bail out at the end of a mission while the rear fuselage containing the rocket motor descended under its own parachute. Other designs, such as the Focke-Wulf Volksjäger 2, sought to overcome this problem by means of a very short fuselage design. Instead of having a wheeled undercarriage most rocket-powered planes that were able to land had only a fixed skid.[3]

Such simplified and dangerous planes were the products of the last phase of the Third Reich, when the lack of materials and the dire need for a strong defense against the Allied bombing raids required such craft to be built quickly in underground factories. During this period the Nazi authorities also considered the use of selbstopfer (suicide) planes such as the Reichenberg (a manned version of the V-1 flying bomb),[3] and in one case of actual use, a "special detachment" unit dedicated to desperate aerial ramming tactics, known as Sonderkommando Elbe.

Peoples' Fighter Project

In August 1944, a requirement led to the Volksjäger ("Peoples' Fighter") aircraft design competition, to create a lightweight high-speed fighter/interceptor using a single BMW 003 turbojet engine as specified,[4] intended for rapid mass-production while using minimal resources. The Volksjäger was intended to be disposable, with damaged aircraft being discarded rather than repaired, while it was to be flown by pilots hastily trained on gliders.

After a hurried design competition involving almost all of Germany's aircraft companies, including Zeppelin with its Fliegende Panzerfaust, Heinkel's He 162 proposal was selected as the winning Volksjäger airframe design.[5] The first prototype of the He 162 Spatz (Sparrow), flew in December 1944.[6] Other designs submitted to the Peoples' Fighter Programme, such as the Blohm & Voss P 211, were potentially superior, but never proceeded past the project stage.[7]

Miniature Fighter Project

In November 1944, a programme for an even simpler fighter, the so-called Miniaturjägerprogramm ("Miniature Fighter Program") was launched. The aim was to develop and mass-produce a very small interceptor using the absolute minimum of strategic materials. Linked to Nazi propaganda, stress was laid on producing the fighter planes cheaply and in large numbers so as to overwhelm the Allied bomber formations that flew daily over Germany.[3] The Miniaturjäger would be powered by one Argus As 014 pulsejet engine per unit, as this engine required far fewer construction man-hours, than the 375 man-hours[8] needed to build a Junkers Jumo 004 turbojet.[9] The various German aircraft designers showed less interest in this new enterprise than in the Peoples' Fighter Project for the imminent He 162 program would swallow up most of what was left of the country's available — and rapidly diminishing — production capacity. Furthermore, it was already well known by the time the Miniaturjäger competition was announced that, as they didn't produce enough power at low speeds for takeoff, the Argus pulsejets were unsuitable for manned aircraft that would have to takeoff unassisted. Since additional launch schemes would have to be added to the project, such as towplanes, catapults or rocket boosters, the goal of the program would be defeated as complexity and expense would be far higher.[1] Thus the Miniaturjäger project never saw mass-production, being abandoned by December 1944.

Even so, aircraft manufacturers Heinkel, Blohm & Voss and Junkers came up with light fighter designs using a strict minimum of materials before that date. The resulting planes were small, spartan creations, with no radio and almost no electrical equipment, Heinkel would use a He 162 air frame powered by a pulse jet, Blohm & Voss designed the BV P 213 and Junkers would submit the Ju EF 126 Elli project.[10] The only Miniature Fighter aircraft to get beyond blueprint status was the Junkers EF 126. Although unbuilt during the war, five prototypes were built in the Dessau Junkers plant in the area occupied by the Soviet Union. One of the prototypes was destroyed during unpowered testing in 1946, killing the pilot.[11]

Other projects

At the beginning of 1945 a further programme was launched by the OKL in order to replace the He 162 Volksjäger. The new aircraft was intended to have superior performance in order to deal with future high altitude threats such as the B-29 Superfortress, which eventually never saw action in Europe owing to the end of the war.[12] To meet this requirement, power was to be a single Heinkel HeS 011 turbojet, of which only 19 examples were ever produced, and all allocated for development testing. The designs of the Messerschmitt P.1110,[13] Heinkel P.1078, Focke-Wulf Ta 183, Blohm & Voss P 212 as well as the official winner of the competition, the Junkers EF 128, were submitted by February 1945.[14]

Only the Messerschmitt prototype of this more advanced fighter had been started by the end of the war.[15] The first prototype of the Messerschmitt P.1101 was 80% complete when captured at the end of the war, following which it was taken to America, with some of its design ideas used as the basis of the solely American-built Bell X-5 variable geometry research aircraft.[16]

List of Third Reich emergency fighter projects

Gliders

Pulsejet-powered aircraft

- Blohm & Voss P 213

- Junkers EF 126 Elli

- Heinkel He 162 B

- Heinkel P.1077 Romeo

- Messerschmitt Me 328

- Messerschmitt P.1079 1, 2, 10c, 13b, 15 and 16

Ramjet-powered aircraft

Rocket-powered aircraft

- Arado E.381 Kleinstjäger

- Bachem Ba 349 Natter

- DFS Eber

- DFS Rammer

- Focke-Wulf Volksjäger 2

- Heinkel P.1077 Julia

- Junkers EF 127 Walli

- Messerschmitt P.1103

- Messerschmitt P.1104

- Sombold So 344

- Stöckel Rammschussjäger

- Von Braun Interceptor

- Zeppelin Fliegende Panzerfaust

- Zeppelin Rammer

Turbojet-powered aircraft

References

- The Heinkel He-162 Volksjaeger

- Heinkel He P.1077 (Julia) Rocket-Powered Interceptor - History

- Ulrich Albrecht. "Artefakte des Fanatismus; Technik und nationalsozialistische Ideologie in der Endphase des Dritten Reiches". Wissenschaft & Frieden 1989-4. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- Christopher, John. The Race for Hitler's X-Planes (The Mill, Gloucestershire: History Press, 2013), p.145.

- Smith and Kay 1972, pp. 307–308.

- Smith and Kay 1972, p.308.

- "Blohm & Voss BV P.211 Luft '46 entry". Luft46.com. Retrieved 2013-05-01.

- Christopher, John. The Race for Hitler's X-Planes (The Mill, Gloucestershire: History Press, 2013), p.75.

- Smith and Kay 1972, p.614.

- "Blohm & Voss BV P.213 Luft '46 entry". Luft46.com. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Junkers Ef-126 "Lilli"

- Sternenbanner announcement of the B-29 in German, comparing it to the B-17 in size

- Peter Allen's Aircraft Profiles - Fighters luft46.com

- Karl-Heinz Ludwig, Technik und Ingenieure im Dritten Reich. Athenäum-Verlag, Königstein/Ts., 1979, ISBN 3761072198

- Smith and Kay 1972, pp. 626–628.

- Smith and Kay 1972, pp. 622–624.

Bibliography

- Smith, J.R. and Kay, Antony L. German Aircraft of the Second World War. London: Putnam, 1972. ISBN 0-85177-836-4.