Environmental politics

Environmental politics designate both the politics about the environment[1] (see also environmental policy) and an academic field of study focused on three core components:[2]

- The study of political theories and ideas related to the environment;

- The examination of the environmental stances of both mainstream political parties and environmental social movements; and

- The analysis of public policymaking and implementation affecting the environment, at multiple geo-political levels.

Neil Carter, in his foundational text Politics of the Environment (2009), suggests that environmental politics is distinct in at least two ways: first, "it has a primary concern with the relationship between human society and the natural world" (page 3); and second, "unlike most other single issues, it comes replete with its own ideology and political movement" (page 5, drawing on Michael Jacobs, ed., Greening the Millenium?, 1997).[2]

Further, he distinguishes between modern and earlier forms of environmental politics, in particular conservationism and preservationism. Contemporary environmental politics "was driven by the idea of a global ecological crisis that threatened the very existence of humanity." And "modern environmentalism was a political and activist mass movement which demanded a radical transformation in the values and structures of society."[2]

Environmental concerns were rooted in the vast social changes that took place in the United States after World War II. Although environmentalism can be identified in earlier years, only after the war did it become widely shared social priority. This began with outdoor recreation in the 1950s, extended into the wider field of the protection of natural environments, and then became infused with attempts to cope with air and water pollution and still later with toxic chemical pollutants. After World War II, environmental politics became a major public concern.[3] The development of environmentalism in the United Kingdom emerged in this period following the great London smog of 1952 and the Torrey Canyon oil spill of 1967.[4] This is reflected by the emergence of Green politics in the Western world beginning in the 1970s.

Democratic challenges

Climate change is slow relative to political cycles of leadership in electoral democracies, which impedes responses by politicians who are elected and re-elected on much shorter timescales.[5]

In the United States, although "environmentalism" was once considered a White phenomenon, scholars have identified "pro-environment positions among Latino, African-American, and non-Hispanic white respondents," with growing environmental concern especially among Latinos.[6] Other scholars have similarly noted that Asian Americans are strongly pro-environmental, with some variation among ethnic subgroups.[7]

Effectively responding to global warming necessitates some form of international environmental governance to achieve shared targets related to energy consumption and environmental usage.[8] Climate change complicates political ideology and practice, affecting conceptions of responsibility for future societies as well as economic systems.[8] Material inequality between nations make technological solutions insufficient for climate change mitigation.[8] Rather, political solutions can navigate the particularities of various facets of environmental crisis. Climate change mitigation strategies can be at odds with democratic priorities of prosperity, progress, and state sovereignty, and instead underscore a collective relationship with the environment.

The international political community is presently based on liberal principles that prioritize individual freedoms and capitalist systems that make quick and ambitious climate responses difficult.[8] Interest-group liberalism is guided by individual human priorities.[9] Groups unable to voice their self-interest, such as minorities without suffrage, or non-humans, are not included in the political compromise. Addressing environmental crises can be impeded when citizens of liberal democracies do not see environmental problems as impacting their lives, or when they lack the education to evaluate the importance of the problem.[10] The human benefits from environmental exploitation and protection compete.[10] Considering the implications of ecological degradation for future human generations can give environmental concerns a basis in anthropocentric liberal democratic politics.

William Ophuls posits that liberal democracies are unfit to address environmental problems, and that the prioritization of these challenges would involve a transition to more authoritarian forms of government.[11] Others counter this by pointing to the past successes of environmental reform movements to improve water and air quality in liberal societies.[9] In practice, environmentalism can improve democracy rather than necessitate its end, by expanding democratic participation and promoting political innovations.[12]

The tensions between liberal democracy and environmental goals raise questions about the possible limitations of democracy (or at least democracy as we know it): in its responsiveness to subtle but large-scale problems, its ability to work from a holistic societal perspective, its aptness in coping with environmental crisis relative to other forms of government.[10] Democracies do not have the provisions to make environmental reforms that are not mandated by voters, and many voters lack incentives or desire to demand policies that could compromise immediate prosperity. The question arises as to whether the foundation of politics is morality or practicality.[10] A scheme that conceives of and values the environment beyond its human utility, an environmental ethics, could be crucial for democracies to respond to climate change.[10]

Alternative forms of democracy for environmental policy

In political theory, deliberative democracy has been discussed as a political model more compatible with environmental goals. Deliberative democracy is a system in which informed political equals weigh values, information, and expertise, and debate priorities to make decisions, as opposed to a democracy based on interest aggregation.[13] This definition of democracy emphasizes informed discussion among citizens in the decision making process, and encourages decisions to benefit the common good rather than individual interests.[9] Amy Gutmann and Dennis Thompson claimed that reason prevails over self-interest in deliberative democracy, making it a more just system.[14] The broad perspective that this discursive model encourages could lead to a stronger engagement with environmental concerns.[9] When compared to non-democracies, democracies are in fact more cooperative in climate change policy creation, but not necessarily on the outcome and effects of these policies.[15]

This can be explained more exhaustively with the concept of grass-roots democracy. Grass-roots democracy is an approach in which ordinary citizens are in charge of politics, in opposition to ‘larger organizations and wealthy individuals with concentrated vested interests in particular policies’.[16] Green parties were once dedicated to offer a project valuing the ideology of grass-roots democracy. However, according to Ostrogorski [17] and Michels,[18] all parties follow inevitably a similar path towards concentration of power and oligarchy. Green parties thus follow different principles nowadays. [19]

In political theory, the lottery system is a democratic design that allows governments to address problems with future, rather than immediate, impacts. Deliberative bodies composed of randomly selected representatives can draft environmental policies that have short-term costs without considering the political consequences for re-election.[5]

New materialism and environmental justice

New materialism is a strain of thought in philosophy and the social sciences that conceives of all material as having life or agency.[20] It criticizes frameworks of justice that center on human attributes like consciousness as insufficient for modern ethical problems that concern the natural environment. It is a post-humanist consideration of all matter that rejects arguments of utility that privilege humans. This politically relevant social theory combats inequality beyond the interpersonal plane.[21] People are ethically responsible for one another, and for the physical spaces they navigate, including animal and plant life, and the inanimate matter that sustains it, like soil. New materialism encourages political action according to this world vision, even if it is incompatible with economic growth.[21]

Jane Bennett uses the term "vital materialism" in her book Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. She develops the concept of materialism with the aim of providing a stronger basis in political theory for environmental politics.

New materialists have invoked Derrida and other historical thinkers to trace the emergence of their philosophy and to justify their environmental claims:[22]

"No justice ... seems possible or thinkable without the principle of some responsibility, beyond all living present, within that which disjoins the living present, before the ghosts of those who are not yet born or who are already dead [...]. Without this non-contemporaneity with itself of the living present ... without this responsibility and this respect for justice concerning those who are not there, of those who are no longer or who are not yet present and living, what sense would there be to ask the question 'where?' 'where tomorrow?' 'whither?'"[23]

All material, living and dead, is interrelated in "the mesh" as described by Timothy Morton. As all matter is interdependent, humans have obligations to all parts of the material world, including those that are unfamiliar.

New materialism is related to a shift from the view of the environment as a form of capital to a form of labor (see Ecosystem services).[24]

Emerging nations

Brazil, Russia, India, and China (known as the "BRIC" nations) are rapidly industrializing, and are increasingly responsible for global carbon emissions and the associated climate change. Other forms of environmental degradation have also accompanied the economic growth in these nations.[25] Environmental degradation tends to motivate action more than the threat of global warming does, since air and water pollution cause immediate health problems, and because pollutants can damage natural resources, hampering economic potential.[25]

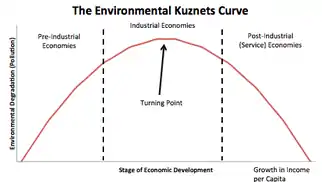

With rising incomes, environmental degradation tends to decrease in industrializing nations, as depicted in the Environmental Kuznets Curve (described in a section of the Kuznets Curve article). Citizens demand better air and water quality, and technology becomes more efficient and clean when incomes increase.[25] The level of income per capita needed to reverse the trend of environmental degradation in industrializing nations varies with the environmental impact indicator.[26] More developed nations can facilitate eco-friendly transitions in emerging economies by investing in the development of clean technologies.

Laws implemented in response to environmental concerns vary by nation (see List of environmental laws by country).

China

China's environmental ills include acid rain, severe smog, and a reliance on coal-burning for energy.[27] China has instated environmental policies since the 1970s, and has one of the most extensive environmental conservation programs on paper.[28] However, regulation and enforcement by the central government in Beijing are weak, so solutions are decentralized. Wealthier provinces are far more effective in their preservation and sustainable development efforts than poorer regions.[27] China therefore provides an example of the consequences of environmental damage falling disproportionately on the poor.[29] NGOs, the media, and the international community have all contributed to China's response to environmental problems.[27]

For history, laws, and policies, see Environmental policy in China.

India

In 1976, the Constitution of India was amended to reflect environmental priorities, motivated in part by the potential threat of natural resource depletion to economic growth:

"The State shall endeavour to protect and improve the environment and to safeguard the forests and wildlife." (Art. 48A)

"It shall be the duty of every citizen of India [...] to protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers and wildlife, and to have compassion for living creatures." (Art. 51A)

However, in India, as in China, the implementation of written environmental policies, laws, and amendments has proven challenging. Official legislation by the central government (see a partial list at Environmental policy of the Government of India) is often more symbolic than practical.[30] The Ministry of Environment and Forests was established in 1985, but corruption within bureaucratic agencies, namely the influence of wealthy industry leaders, limited any attempts at enforcement of the policies put in place.[30]

Journals

Scholarly journals representing this field of study include:

- Environmental Politics

- Global Environmental Politics

- International Environmental Agreements

See also

References

- Andrew Dobson, Environmental Politics: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2016 (ISBN 978-0-19-966557-0).

- Carter, Neil. 2007. The Politics of the Environment: Ideas, Activism, Policy, 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-68745-4

- Hays, Samuel P., and Barbara D. Hays. Beauty, Health, and Permanence: Environmental Politics in the United States, 1955-1985. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1987. Print.

- "The British environmental movement: The development of an environmental consciousness and environmental activism, 1945-1975". April 2014.

- Guerrero, Alexander (2014). "Against Elections: The Lottocratic Alternative" (PDF). Philosophy & Public Affairs. 42 (2): 135–178. doi:10.1111/papa.12029.

- Whittaker, Matthew, Segura, and Bowler, Shaun (2005). "Racial/Ethnic Group Attitudes Toward Environmental Protection in California: Is "Environmentalism" Still a White Phenomenon?" Political Research Quarterly (58)3: pp. 435, 435-447.

- Ong, Paul; Le, Loan; Daniels, Paula (2013). "Ethnic Variation in Environmental Attitudes and Opinion among Asian American Voters". Aapi Nexus: Policy, Practice and Community. 11 (1–2): 91–109. doi:10.17953/appc.11.1-2.958537240526x56v.

- Edmondson and Levy (2013). Climate Change and Order. pp. 50–60.

- Baber and Bartlett (2005). Deliberative Environmental Politics.

- Mathews, Freya (1991). "Democracy and the Ecological Crisis". Legal Service Bulletin.

- Ophuls, William (1977). Ecology and the Politics of Scarcity. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company.

- Paehlke, Robert (1988). "Democracy, Bureaucracy and Environmentalism". Journal of Environmental Ethics. 10 (4): 291–308. doi:10.5840/enviroethics198810437.

- Fishkin, James (2009). When the People Speak. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199604432.

- Gutmann and Thompson, Amy and Dennis (2004). "Why Deliberative Democracy". Princeton University Press.

- Bättig, Michèle B.; Bernauer, Thomas (15 April 2009). "National Institutions and Global Public Goods: Are Democracies More Cooperative in Climate Change Policy?". International Organization. 63 (2): 281–308. doi:10.1017/S0020818309090092. hdl:20.500.11850/19435.

- "Grassroots-democracy Meaning | Best 1 Definitions of Grassroots-democracy". www.yourdictionary.com. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

- Ostrogorski, Moisey (1902). Democracy and the Organization of Political Parties. New York: Macmillan.

- Michels, Robert (1911). Zur Soziologie des Parteiwesens in der modernen Demokratie; Untersuchungen über die oligarchischen Tendenzen des Gruppenlebens. Leipzig: Werner Klinkhardt.

- Frankland, E.G., Lucardie, P. and Rihoux, B. (2008). Green Parties in Transition: The End of Grass-roots Democracy?. Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-7429-0.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Coole and Frost (2010). New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics. United States: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822392996.

- Newman, Lance (2002). "Marxism and Ecocriticism". Interdiscip Stud Lit Environ. 9 (2): 1–25. doi:10.1093/isle/9.2.1.

- Dolphijn and van der Tuin, Rick and Iris (2012). New Materialism: Interviews and Cartographies. Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press. pp. 67–68.

- Derrida, Jacques (1993). Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. New York and London: Routledge.

- Holiday, Sara Nelson (2015). "Beyond The Limits to Growth: Ecology and the Neoliberal Counterrevolution". Antipode. 47 (2): 461–480. doi:10.1111/anti.12125.

- Shaw, William (1 March 2012). "Will Emerging Economies Repeat the Environmental Mistakes of their Rich Cousins?". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08.

- Stern, David (June 2003). "The Environmental Kuznets Curve" (PDF). The International Society for Ecological Economics.

- Economy, Elizabeth (27 January 2003). "China's Environmental Challenge: Political, Social and Economic Implications". Council on Foreign Relations.

- MacBean, Alasdair (2007). "China's Environment: Problems and Policies". The World Economy. 30 (2): 292–307. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2007.00883.x. S2CID 154594885.

- "Combating Environmental Degradation". Investing in Rural People. International Fund for Agricultural Development.

- Dembowski, Hans (2001). Taking the State to Court: Public Interest Litigation and the Public Sphere in Metropolitan India. online: Asia House. pp. 63–84.

External links

- Environmental Politics journal homepage