Erlkönig (Schubert)

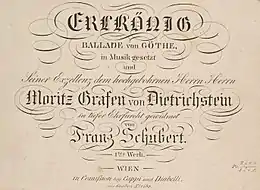

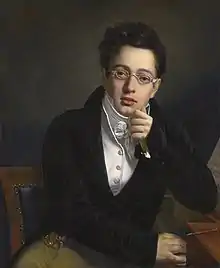

"Erlkönig", Op. 1, D 328, is a Lied composed by Franz Schubert in 1815, set to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's poem of the same name.[1] It is one of Schubert's most famous works, with enduring popularity and acclaim since its premiere in 1821, and has been called one of the "commanding compositions of the century".[2][3]

History

Goethe's poem was set in music by some hundred composers, among them prominent Lied composers like Johann Friedrich Reichardt, Carl Friedrich Zelter and Carl Loewe, though none of them would become as preeminent as Schubert's work, which stands among the most performed, reworked and recorded compositions every written.[4]

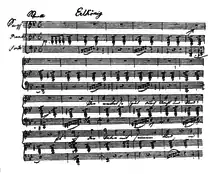

Schubert composed "Erlkönig" at the age of 17 or 18 in 1815 – Joseph von Spaun claims that it was written in a few hours one afternoon.[5] He revised the song three times before publishing his fourth version in 1821 as his Opus 1. The work was first performed in concert on 1 December 1820 at a private gathering in Vienna. The public premiere on 7 March 1821 at the Theater am Kärntnertor was a great success, and he quickly rose to fame among the composers in Vienna.[4][6]

Publication history

"Erlkönig" exists in four versions by Schubert's hand,[1] with the 3rd version featuring a simplified piano accompaniment without triplets in the right hand. The original (for medium voice) is in the key of G minor, though there are also transposed editions for high and low voice.

Structure and musical analysis

Schubert's adaptation of "Erlkönig" is a highly romantic musical realization that represents the various rational and irrational elements of Goethe's ballad by contrasting yet unifying musical elements.[7]

"Erlkönig" is through-composed; although the melodic motives recur, the harmonic structure is constantly changing and the piece modulates within the four characters.

Characters

The four characters in the song – narrator, father, son, and the Erlking – are all sung by a single vocalist. Schubert places each character largely in a different tessitura, and each has his own rhythmic and harmonic nuances;[8] in addition, most singers endeavor to use a different vocal coloration for each part.

- The narrator lies in the middle range and begins in the minor mode.

- The father lies in the lower range and sings in both minor and major mode.

- The son lies in a higher range, also in the minor mode.

- The Erlking's vocal line, in the major mode, provides the only break from the ostinato bass triplets in the accompaniment until the boy's death.

A fifth character, the horse, is implied in rapid triplet figures played by the pianist throughout the work, mimicking hoof beats.[9]

Structure

| External audio | |

|---|---|

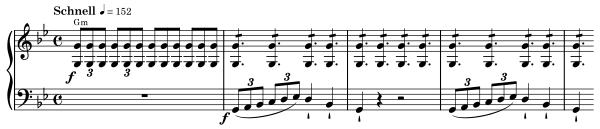

"Erlkönig" begins with the piano playing rapid triplets to create a sense of urgency and simulate the horse's galloping.[10] The moto perpetuo triplets continue throughout the entire song except for the final three bars and mostly comprise the uninterrupted repeated chords or octaves in the right hand, established at the opening.

The left hand of the piano part introduces a ominous bass motif composed of rising scale in triplets and a falling arpeggio, pointing to the background of the scene and suggesting the urgency of the father's mission. It also introduces a chromatic "passing note motif" consisting of C–C♯-D that represents a daemonic force, and used throughout the work.[2]

Verse 1

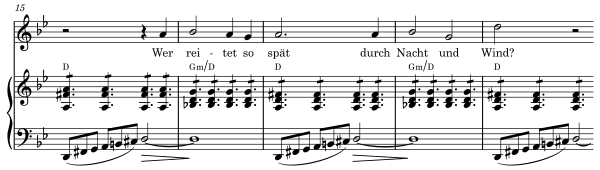

Wer reitet so spät durch Nacht und Wind? |

Who rides, so late, through night and wind? |

After a long introduction of fifteen measures, the narrator raises the question "Wer reitet so spät durch Nacht und Wind?" and accentuates the key words "Vater" (father) and "seinem Kind" (his child) in the reply. A link between "Wind" and "Kind" is suggested in the placement in a major tonality. The verse ends where it started, in G minor, seemingly indicating the narrator's neutral point of view.[8]

Verse 2

"Mein Sohn, was birgst du so bang dein Gesicht?" |

"My son, why do you hide your face in fear?" |

The father's question to his son is harmonically supported by a modulation from the tonic to the subdominant, also employing the "passing note motif" from the introduction. The son's distress is represented by the high pitch of this reply and the repetitive nature of the phrase. As the child mentions the Erlking, the harmony passes into F major, representing a gravitation from the father's tonality to the Erlking.[8] The father calms the son, which is expressed by the low register of the singing voice.

Verse 3

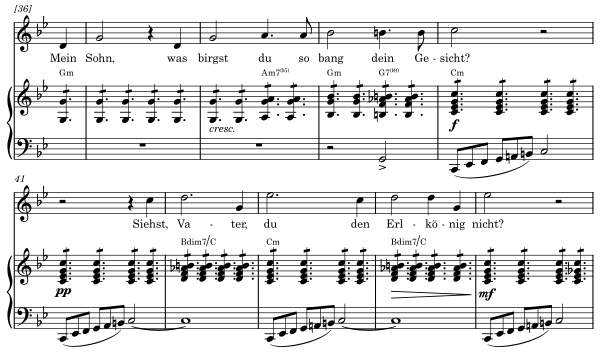

"Du liebes Kind, komm, geh mit mir! |

"You dear child, come, go with me! |

After a short piano interlude, the Erlkönig starts to address the boy in a charming, flattering melody in B♭ major, placing emphasis on the words "liebes" (dear) and "geh" (go). The descending intervals of the melody seems to provide a soothing response to the boy's fear. Though the Erlking's seductive verses differ in their accompanying figurations (providing some relief for the pianist), they are still based on triplets, underscoring his daemonic presence. The "passing note motif" is used twice.[8]

Verse 4

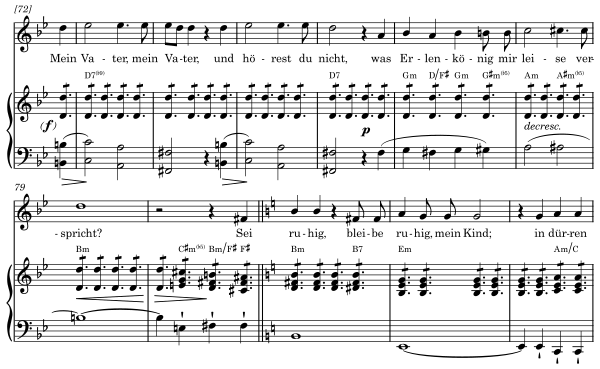

"Mein Vater, mein Vater, und hörest du nicht, |

"My father, my father, and do you not hear |

The son's fear and anxiety in response to the Erlking's words is highlighted by the immediate resumption of the original triplet motif, just after the Erlking finishes. The chromaticism in the son's melody indicates a call to his father, creating dissonances between the vocal part and the bass that depict the boy's horror. The harmonic instability in this verse suggests the child's feverish wandering. The father's tonal center becomes increasingly distant from the child's, suggesting a rivalry over possession of the boy with the Erlking.[11]

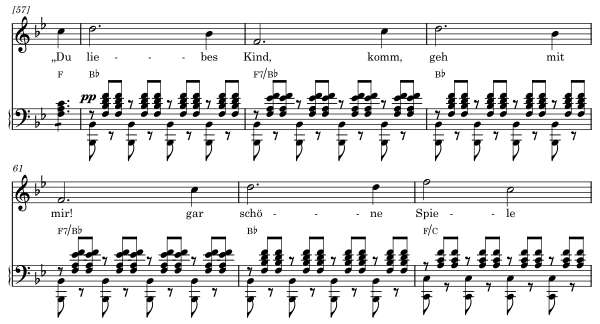

Verse 5

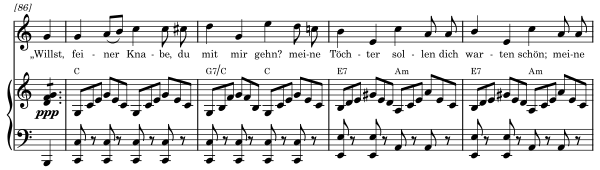

"Willst, feiner Knabe, du mit mir gehn? |

"Do you, fine boy, want to go with me? |

The Erlkönig's enticement intensifies. The piano accompaniment transforms into flowing major arpeggios that can suggest both dances of the Erlking's daughters and the troubled half-sleep of the child. The presence of the daemonic is once again highlighted by the "passing note motif". As in the Erlking's first verse, the octave triplets resume immediately after the verse.[11]

Verse 6

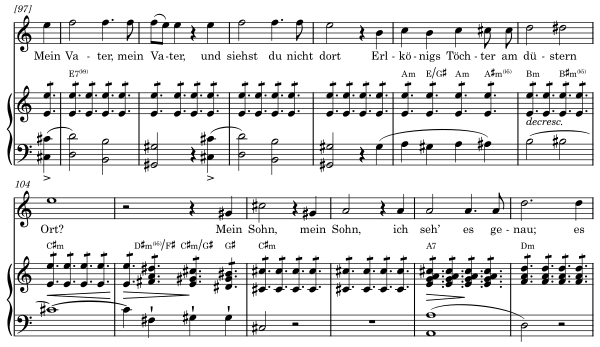

"Mein Vater, mein Vater, und siehst du nicht dort |

"My father, my father, and don't you see there |

The son cries out to his father, his fear again illustrated in rising pitch and chromaticism.[11]

Verse 7

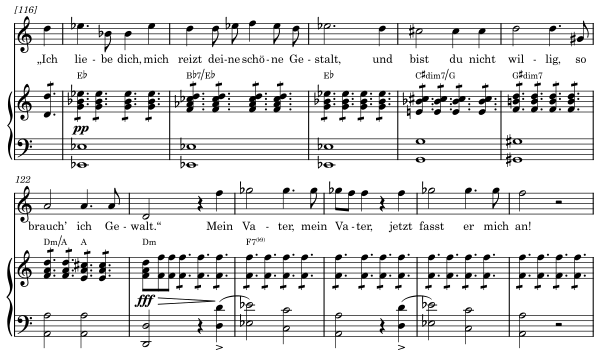

"Ich liebe dich, mich reizt deine schöne Gestalt; |

"I love you, your beautiful form excites me; |

Before the Erlking speaks again, the ominous bass motif foreshadows the outcome of the song. The Erlkönig's luring now becomes more insistent. He threatens the boy, the initial lyricism and playfulness yielding to a measured declamation, with the "passing note motif" being voiced both in the treble and in the bass. Upon the word "Gewalt" (force), the tonality modulates from E♭ major to D minor, with the Erlking appropriating the minor tonality originally associated with the father and his child. The boy cries out to his father a final time, heard in fff. The "passing note motif" on the word "Erlkönig" suggest that the fate of the child is sealed.[12]

Verse 8

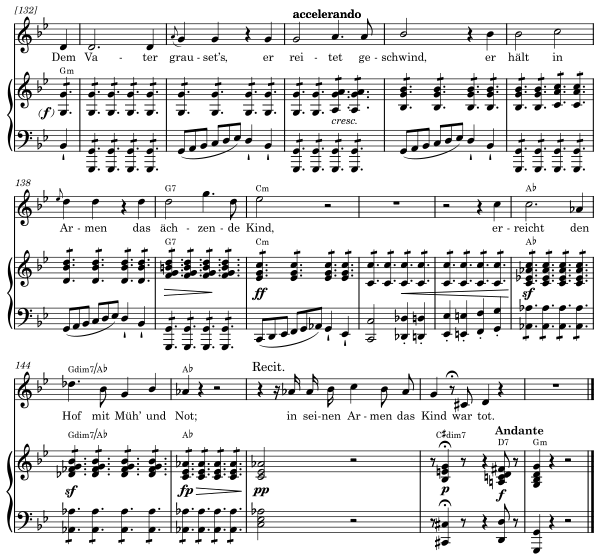

Dem Vater grausets, er reitet geschwind, |

It horrifies the father, he swiftly rides on, |

The music intensifies further, Schubert once again creating tension through the "galloping motif".[13] The grace notes in the voice line suggest the father's horror, and the music accelerates on the words "er reitet geschwind" (he swiftly rides on). A final allusion to the father's tonality of C minor is followed by the Neapolitan chord of A♭ major, as the father spurs his horse to go faster and then arrives at his destination. Before this chord is resolved, the triplet motif stops, and the final rendition of the "passing note motif" in the bass seals the fate of the boy.[14]

The recitative, in absence of the piano, draws attention to the dramatic text and amplifies the immense loss and sorrow caused by the Son's death.

The resolution of C♯ to D major implies a "submission to the daemonic forces", followed by the final cadence delivering "a perfect consummation to the song".[14]

Tonality

The song has a tonal scheme based on rising semitones which portrays the increasingly desperate situation:

| Verse | Measures | Tonality | Character |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–15 | G minor | (Introduction) | |

| 1 | 16–36 | G minor | Narrator |

| 2 | 37–57 | G minor → B♭ major | Father and Son |

| 3 | 58–72 | B♭ major | Erlking |

| 4 | 72–85 | (D7) → B minor | Son |

| → G major | Father | ||

| 5 | 86–96 | C major | Erlking |

| 6 | 97–116 | (E7) → C♯ minor | Son |

| D minor | Father | ||

| 7 | 117–131 | E♭ major → D minor | Erlking |

| (F7) → G minor | Son | ||

| 8 | 132–147 | G minor | Narrator |

The "Mein Vater, mein Vater" music appears three times on a prolonged dominant seventh chord that slips chromatically into the next key. Following the tonal scheme, each cry is a semitone higher than the last, and, as in Goethe's poem, the time between the second two cries is less than the first two, increasing the urgency like a large-scale stretto. Much of the major-key music is coloured by the flattened submediant, giving it a darker, unsettled sound.

Reception and legacy

The premiere in 1821 was an immediate success; the large audience broke out in "rapturous applause", as Joseph von Spaun reported.[15] During the 1820s and 30s, "Erlkönig" was unanimously acclaimed among the Schubert circle, critics and general audiences, with critics hailing the work as "a masterpiece of musical painting", "a composition full of fantasy and feeling, which had to be repeated", "an ingenious piece" that leaves an "indelible impression". No other performance of Schubert's work during his lifetime would receive more attention than "Erlkönig".[16]

Joseph von Spaun sent the composition to Goethe, hoping to receive his approval for a print. The latter, however, sent it back without comment, as he categorically rejected Schubert's form of the through-composed song.[17] However, Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient performed the Erlkönig once again before Goethe in 1830, who is reported by Eduard Genast to have said: "I have heard this composition once before, when it did not appeal to me at all; but sung in this way the whole shapes itself into a visible picture".[18][19]

"Erlkönig" has had enjoyed enduring popularity since its inception to this day.[2] Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau has highlighted the piano accompaniment in the setting, which he describes as having a "compositional life of its own", with important motifs such as the repeated octaves that create an eerie, suspenseful atmosphere.[20] Furthermore, Fischer-Dieskau praised the "magnificent tragedy" of the setting.[21]

The piece is regarded as challenging to perform due to the multiple characters the vocalist is required to portray, as well as its difficult accompaniment, involving rapidly repeated chords and octaves.

Arrangements

| External audio | |

|---|---|

"Erlkönig" has been arranged for various settings: for solo piano by Franz Liszt (1879; S. 558/4), for solo voice and orchestra by Hector Berlioz (1860; H. 136, NBE 22b), Franz Liszt (1860; S. 375/4) and Max Reger, and for solo violin by Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (Grand Caprice für Violine allein, Op. 26).

References

- Deutsch 1983.

- Bodley 2003, p. 228.

- Gibbs 1997, p. 8.

- Gibbs 1995, p. 115.

- Gibbs 1997, p. 38.

- Gibbs 1997, p. 150.

- Antokoletz 2016, p. 140.

- Bodley 2003, p. 229.

- Machlis & Forney 2003.

- Schläbitz 2011, p. 50.

- Bodley 2003, p. 230.

- Bodley 2003, pp. 230–231.

- Fischer-Dieskau 1976.

- Bodley 2003, pp. 231.

- Fischer-Dieskau 1996, p. 79.

- Gibbs 1995, p. 117.

- Dürr 2010, p. 67.

- Düring 1972, p. 109.

- Antokoletz 2016, p. 147.

- Fischer-Dieskau 1976, p. 168.

- Fischer-Dieskau 1976, p. 68.

Sources

- Antokoletz, Elliott (2016). "Sturm und Drang Spirit in Early Nineteenth-Century German Lieder: the Goethe-Schubert 'Erlkönig'". International Journal of Musicology. 2: 139–147. ISSN 0941-9535.

- Bodley, Lorraine Byrne (2003). Schubert's Goethe Settings. London: Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-0695-3.

- Deutsch, Otto Erich (1983). Franz Schubert. Verzeichnis seiner Werke in chronologischer Folge (in German) (Kleine Ausgabe aufgrund der Neuausgabe in deutscher Sprache ed.). München: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 3-423-03261-8.

- Düring, Werner-Joachim (1972). Erlkönig-Vertonungen. Eine historische und systematische Untersuchung (in German). Regensburg: Gustav Bosse. ISBN 3-7649-2082-3.

- Dürr, Walther (2010). Schubert Handbuch (in German) (3rd ed.). Kassel: Bärenreiter. ISBN 978-3-476-02380-3.

- Fischer-Dieskau, Dietrich (1976). Auf den Spuren der Schubert-Lieder. Werden - Wesen - Wirkung (in German). Kassel: dtv Verlagsgesellschaft. ISBN 3-7618-0550-0.

- Fischer-Dieskau, Dietrich (1996). Schubert und seine Lieder (in German). Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. ISBN 3-421-05051-1.

- Gibbs, Christopher H. (1995). ""Komm, geh' mit mir": Schubert's Uncanny "Erlkönig"". 19th-Century Music. 19 (2): 115–135. doi:10.2307/746658. ISSN 0148-2076.

- Gibbs, Christopher Howard (1997). The Cambridge Companion to Schubert (1st ed.). Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-48229-1.

- Machlis, Joseph; Forney, Kristine (2003). The Enjoyment of Music: An Introduction to Perceptive Listening (9th ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

- Schläbitz, Norbert (2011). Romantik in der Musik (in German). Paderborn: Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh. ISBN 978-3-14-018072-6.

Further reading

- Stein, Deborah (1989). "Schubert's 'Erlkönig:' Motivic Parallelism and Motivic Transformation". 19th-Century Music. 13 (2): 145–158. doi:10.2307/746652. ISSN 0148-2076.

External links

- Erlkönig, D.328: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Harmonic analysis on YouTube by David Bennett Thomas