Ermenrichs Tod

Ermenrichs Tod or Koninc Ermenrîkes Dôt (the death of king Ermenrich) is an anonymous Middle Low German heroic ballad from the middle of the sixteenth century.

The ballad, which is printed in a highly garbled form, tells the story of how Ermenrich is killed by Dietrich von Bern and several other heroes. The poem shows numerous similarities to older stories about Ermenrich attested in early medieval and Old Norse sources.

Summary

According to the song, Dietrich wants to exile the King of the Franks, van Armentriken, because the latter wants to hang Dietrich. As one of his companions Dietrich receives the gigantic King Blödelinck, who is only twelve years old and is the son of a Frankish widow. Dietrich then sets off to Freysack who the enemy king lives, passing by a set of gallows. He and his companions disguise themselves as dancers and receive an audience with the king before revealing themselves and demanding to know why the king wants to hang Dietrich. When the king is silent, Dietrich cuts off his head and then the twelve proceed to kill everyone in the castle except for Reinholt von Meilan, who is spared due to his loyalty to the king. Blödelinck has disappeared in the fighting and Dietrich assumes he is dead, but the giant reappears.[1]

Printing

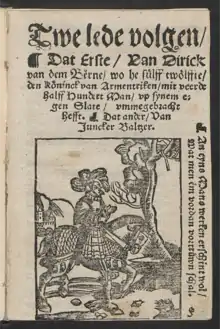

The ballad was originally printed as a broadside titled Van Dirick van dem Berne (concerning Dietrich von Bern) in 1535/45[2] or 1560[3] together with another ballad Juncker Baltzer in Lübeck, and was printed again in a Low German songbook from 1590 or 1600. The broadside is heavily corrupted—possibly the work of a printer famous for his mistakes, Johannes Balhorn the Elder—and not always comprehensible.[2] Victor Millet suggests that it was printed in honor of King Christian II of Denmark, who returned from exile in the Netherlands at this time.[4] Elisabeth Lienert finds this interpretation questionable, however notes that Juncker Baltzer, the text printed alongside Ermenrichs Tod, is clearly about Christian.[5]

Metrical form

The ballad is printed in the so-called "Hildebrandston," a stanzaic metrical form named about another heroic ballad, the Jüngeres Hildebrandslied. No melody has been transmitted with the text, but it was likely meant to be sung.[6] The stanza consists of four "Langzeilen," lines consisting of three metrical feet, a caesura, and three additional metrical feet. Unlike the similar stanza used in the Nibelungenlied, in the "Hildebrandston" all four lines are of the same length. The lines rhyme in couplets, with occasional rhymes across lines at the caesura.[7] An example is the first stanza of the poem as contained in the first printed edition:

- So vern yn yennen Franckriken/ a

- Den wil de Berner vordriuen/ a

- He voert yn synem rike/ b

- Tho weem schal ick my holden/ b

Relation to the oral tradition

Although the text is very late and at times not clear, it nevertheless contains many references to events in the oral tradition about Ermenrich that are otherwise only found in allusions or Scandinavian sources.[8] Lienert notes that it is possible that the ballad comes from a tradition in which Dietrich successfully returns from exile and avenges himself on his wicked uncle.[5] Joachim Heinzle suspects that many of the mistakes come from the composer of the ballad only partially remembering the heroic tradition.[9] Van Armentriken is clearly the legendary Ermenrich, with his name misunderstood as the name of his country. His misidentification as King of the Franks/France may be connected to a note by Johannes Agricola in which a king Ermentfrid (that is, Ermenrich) of the Franks supposedly conquered Lombardy and there killed his nephews known as the Harlungen.[9] Blödelinck is Blödel, i.e. Bleda, Attila's brother, who also appears in the Nibelungenlied and the historical Dietrich poems. Freysack is probably Breisach, which was connected with the Harlungen from an early date. Lastly, Ermenrich's death is reminiscent of the Svanhild episode recorded in the Poetic Edda and other sources, as the sons of Jónakr also pass by a set of gallows on their way to confront Jörmunrekkr.[9] Dietrich's involvement may be a variant of his return from exile – in a variant of the text, it is even said that Ermenrich wanted to drive Dietrich away, not the other way around.[10] Despite the many apparent connections to the oral tradition, Millet believes that it is useless to use Ermenrichs Tod to reconstruct legends about Ermenrich.[4]

Notes

- Heinzle 1999, pp. 52-53.

- Heinzle 1999, p. 53.

- Millet 2008, p. 474.

- Millet 2008, p. 476.

- Lienert 2015, p. 116.

- Lienert 2015, p. 115.

- Heinzle 1999, pp. 85-86.

- Millet 2008, p. 475.

- Heinzle 1999, p. 54.

- Heinzle 1999, p. 54-55.

Editions

- Weddige, Hilkert, ed. (1995). Koninc Ermenrîkes Dôt: Die niederdeutsche Flugschrift "Van Dirick van dem Berne" und "Van Juncker Baltzer": Überlieferung, Kommentar, Interpretation. Tübingen: Niemeyer. ISBN 3484150769.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

References

- Gillespie, George T. (1973). Catalogue of Persons Named in German Heroic Literature, 700-1600: Including Named Animals and Objects and Ethnic Names. Oxford: Oxford University. ISBN 9780198157182.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haug W (1980). "Ermenrikes dot". In Ruh K, Keil G, Schröder W (eds.). Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters. Verfasserlexikon. 2. Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. cols 611–617. ISBN 978-3-11-022248-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haymes, Edward R.; Samples, Susan T. (1996). Heroic legends of the North: an introduction to the Nibelung and Dietrich cycles. New York: Garland. p. 97. ISBN 0815300336.

- Heinzle, Joachim (1999). Einführung in die mittelhochdeutsche Dietrichepik. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter. pp. 53–56. ISBN 3-11-015094-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoffmann, Werner (1974). Mittelhochdeutsche Heldendichtung. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. pp. 171–174. ISBN 3-503-00772-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lienert, Elisabeth (2015). Mittelhochdeutsche Heldenepik. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-3-503-15573-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Millet, Victor (2008). Germanische Heldendichtung im Mittelalter. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter. pp. 474–476. ISBN 978-3-11-020102-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)