Ethanol fermentation

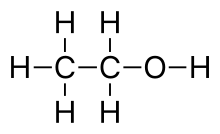

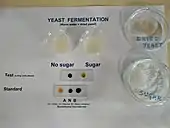

Ethanol fermentation, also called alcoholic fermentation, is a biological process which converts sugars such as glucose, fructose, and sucrose into cellular energy, producing ethanol and carbon dioxide as by-products. Because yeasts perform this conversion in the absence of oxygen, alcoholic fermentation is considered an anaerobic process. It also takes place in some species of fish (including goldfish and carp) where (along with lactic acid fermentation) it provides energy when oxygen is scarce.[1]

Ethanol fermentation has many uses, including the production of alcoholic beverages, the production of ethanol fuel, and bread cooking.

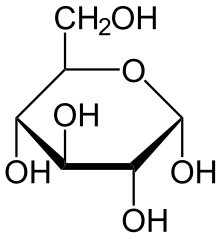

Biochemical process of fermentation of sucrose

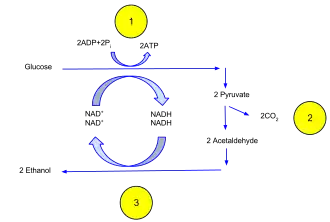

The chemical equations below summarize the fermentation of sucrose (C12H22O11) into ethanol (C2H5OH). Alcoholic fermentation converts one mole of glucose into two moles of ethanol and two moles of carbon dioxide, producing two moles of ATP in the process.

The overall chemical formula for alcoholic fermentation is:

- C6H12O6 → 2 C2H5OH + 2 CO2

Sucrose is a sugar composed of a glucose linked to a fructose. In the first step of alcoholic fermentation, the enzyme invertase cleaves the glycosidic linkage between the glucose and fructose molecules.

- C12H22O11 + H2O + invertase → 2 C6H12O6

Next, each glucose molecule is broken down into two pyruvate molecules in a process known as glycolysis.[2] Glycolysis is summarized by the equation:

- C6H12O6 + 2 ADP + 2 Pi + 2 NAD+ → 2 CH3COCOO− + 2 ATP + 2 NADH + 2 H2O + 2 H+

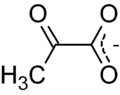

CH3COCOO− is pyruvate, and Pi is inorganic phosphate. Finally, pyruvate is converted to ethanol and CO2 in two steps, regenerating oxidized NAD+ needed for glycolysis:

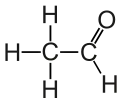

- 1. CH3COCOO− + H+ → CH3CHO + CO2

catalyzed by pyruvate decarboxylase

- 2. CH3CHO + NADH + H+ → C2H5OH + NAD+

This reaction is catalyzed by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH1 in baker's yeast).[3]

As shown by the reaction equation, glycolysis causes the reduction of two molecules of NAD+ to NADH. Two ADP molecules are also converted to two ATP and two water molecules via substrate-level phosphorylation.

Related processes

Fermentation of sugar to ethanol and CO2 can also be done by Zymomonas mobilis, however the path is slightly different since formation of pyruvate does not happen by glycolysis but instead by the Entner–Doudoroff pathway. Other microorganisms can produce ethanol from sugars by fermentation but often only as a side product. Examples are[4]

- Heterolactic acid fermentation in which Leuconostoc bacterias produce Lactate + Ethanol + CO2

- Mixed acid fermentation where Escherichia produce ethanol mixed with lactate, acetate, succinate, formate, CO2, and H2

- 2,3-butanediol fermentation by Enterobacter producing ethanol, butanediol, lactate, formate, CO2, and H2

Effect of oxygen

Fermentation does not require oxygen. If oxygen is present, some species of yeast (e.g., Kluyveromyces lactis or Kluyveromyces lipolytica) will oxidize pyruvate completely to carbon dioxide and water in a process called cellular respiration, hence these species of yeast will produce ethanol only in an anaerobic environment (not cellular respiration). This phenomenon is known as the Pasteur effect.

However, many yeasts such as the commonly used baker's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae or fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe under certain conditions, ferment rather than respire even in the presence of oxygen. In wine making this is known as the counter-Pasteur effect. These yeasts will produce ethanol even under aerobic conditions, if they are provided with the right kind of nutrition. During batch fermentation, the rate of ethanol production per milligram of cell protein is maximal for a brief period early in this process and declines progressively as ethanol accumulates in the surrounding broth. Studies demonstrate that the removal of this accumulated ethanol does not immediately restore fermentative activity, and they provide evidence that the decline in metabolic rate is due to physiological changes (including possible ethanol damage) rather than to the presence of ethanol. Several potential causes for the decline in fermentative activity have been investigated. Viability remained at or above 90%, internal pH remained near neutrality, and the specific activities of the glycolytic and alcohologenic enzymes (measured in vitro) remained high throughout batch fermentation. None of these factors appears to be causally related to the fall in fermentative activity during batch fermentation.

Bread baking

Ethanol fermentation causes bread dough to rise. Yeast organisms consume sugars in the dough and produce ethanol and carbon dioxide as waste products. The carbon dioxide forms bubbles in the dough, expanding it to a foam. Less than 2% ethanol remains after baking.[5][6]

Alcoholic beverages

All ethanol contained in alcoholic beverages (including ethanol produced by carbonic maceration) is produced by means of fermentation induced by yeast.

- Wine is produced by fermentation of the natural sugars present in grapes; cider and perry are produced by similar fermentation of natural sugar in apples and pears, respectively; and other fruit wines are produced from the fermentation of the sugars in any other kinds of fruit. Brandy and eaux de vie (e.g. slivovitz) are produced by distillation of these fruit-fermented beverages.

- Mead is produced by fermentation of the natural sugars present in honey.

- Beer, whiskey, and sometimes vodka are produced by fermentation of grain starches that have been converted to sugar by the enzyme amylase, which is present in grain kernels that have been malted (i.e. germinated). Other sources of starch (e.g. potatoes and unmalted grain) may be added to the mixture, as the amylase will act on those starches as well. It may also be amylase-induce fermented with saliva in a few countries. Whiskey and vodka are also distilled; gin and related beverages are produced by the addition of flavoring agents to a vodka-like feedstock during distillation.

- Rice wines (including sake) are produced by the fermentation of grain starches converted to sugar by the mold Aspergillus oryzae. Baijiu, soju, and shōchū are distilled from the product of such fermentation.

- Rum and some other beverages are produced by fermentation and distillation of sugarcane. Rum is usually produced from the sugarcane product molasses.

In all cases, fermentation must take place in a vessel that allows carbon dioxide to escape but prevents outside air from coming in. This is to reduce risk of contamination of the brew by unwanted bacteria or mold and because a buildup of carbon dioxide creates a risk the vessel will rupture or fail, possibly causing injury or property damage.

Feedstocks for fuel production

Yeast fermentation of various carbohydrate products is also used to produce the ethanol that is added to gasoline.

The dominant ethanol feedstock in warmer regions is sugarcane.[7] In temperate regions, corn or sugar beets are used.[7][8]

In the United States, the main feedstock for the production of ethanol is currently corn.[7] Approximately 2.8 gallons of ethanol are produced from one bushel of corn (0.42 liter per kilogram). While much of the corn turns into ethanol, some of the corn also yields by-products such as DDGS (distillers dried grains with solubles) that can be used as feed for livestock. A bushel of corn produces about 18 pounds of DDGS (320 kilograms of DDGS per metric ton of maize).[9] Although most of the fermentation plants have been built in corn-producing regions, sorghum is also an important feedstock for ethanol production in the Plains states. Pearl millet is showing promise as an ethanol feedstock for the southeastern U.S. and the potential of duckweed is being studied.[10]

In some parts of Europe, particularly France and Italy, grapes have become a de facto feedstock for fuel ethanol by the distillation of surplus wine.[11] Surplus sugary drinks may also be used.[12] In Japan, it has been proposed to use rice normally made into sake as an ethanol source.[13]

Cassava as ethanol feedstock

Ethanol can be made from mineral oil or from sugars or starches. Starches are cheapest. The starchy crop with highest energy content per acre is cassava, which grows in tropical countries.

Thailand already had a large cassava industry in the 1990s, for use as cattle feed and as a cheap admixture to wheat flour. Nigeria and Ghana are already establishing cassava-to-ethanol plants. Production of ethanol from cassava is currently economically feasible when crude oil prices are above US$120 per barrel.

New varieties of cassava are being developed, so the future situation remains uncertain. Currently, cassava can yield between 25-40 tonnes per hectare (with irrigation and fertilizer),[14] and from a tonne of cassava roots, circa 200 liters of ethanol can be produced (assuming cassava with 22% starch content). A liter of ethanol contains circa 21.46[15] MJ of energy. The overall energy efficiency of cassava-root to ethanol conversion is circa 32%.

The yeast used for processing cassava is Endomycopsis fibuligera, sometimes used together with bacterium Zymomonas mobilis.

Byproducts of fermentation

Ethanol fermentation produces unharvested byproducts such as heat, carbon dioxide, food for livestock, water, methanol, fuels, fertilizer and alcohols.[16] The cereal unfermented solid residues from the fermentation process, which can be used as livestock feed or in the production of biogas, are referred to as Distillers grains and sold as WDG, Wet Distiller's grains, and DDGS, Dried Distiller's Grains with Solubles, respectively.

Microbes used in ethanol fermentation

- Yeast

- Zymomonas mobilis (a bacterium)

See also

- Anaerobic respiration

- Cellular respiration

- Cellulose

- Fermentation (wine)

- Yeast in winemaking

- Tryptophol, a chemical compound found in wine[17] or in beer[18] as a secondary product of alcoholic fermentation[19] (a product also known as congener)

References

- Aren van Waarde; G. Van den Thillart; Maria Verhagen (1993). "Ethanol Formation and pH-Regulation in Fish". Surviving Hypoxia. pp. 157−170. hdl:11370/3196a88e-a978-4293-8f6f-cd6876d8c428. ISBN 978-0-8493-4226-4.

- Stryer, Lubert (1975). Biochemistry. W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-0-7167-0174-3.

- Raj SB, Ramaswamy S, Plapp BV. "Yeast alcohol dehydrogenase structure and catalysis". Biochemistry. 53: 5791-803. doi:10.1021/bi5006442. PMC 4165444. PMID 25157460.

- Müller, Volker (2001). "Bacterial Fermentation" (PDF). eLS. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1038/npg.els.0001415. ISBN 9780470015902.

- Logan, BK; Distefano, S (1997). "Ethanol content of various foods and soft drinks and their potential for interference with a breath-alcohol test". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 22 (3): 181–3. doi:10.1093/jat/22.3.181. PMID 9602932.

- "The Alcohol Content of Bread". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 16 (11): 1394–5. November 1926. PMC 1709087. PMID 20316063.

- James Jacobs, Ag Economist. "Ethanol from Sugar". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 2007-09-10. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- "Economic Feasibility of Ethanol Production from Sugar in the United States" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. July 2006. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2007-08-15. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- "Ethanol Biorefinery Locations". Renewable Fuels Association. Archived from the original on 30 April 2007. Retrieved 21 May 2007.

- "Tiny super-plant can clean up hog farms and be used for ethanol production". projects.ncsu.edu. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- Caroline Wyatt (2006-08-10). "Draining France's 'wine lake'". BBC News. Retrieved 2007-05-21.

- Capone, John (21 November 2017). "That unsold bottle of Merlot is probably winding up in your gas tank". Quartz. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- Japan Plans Its Own Green Fuel by Steve Inskeep. NPR Morning Edition, May 15, 2007

- "Agro2: Ethanol From Cassava". Archived from the original on 2016-05-19. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- Pimentel, D. (Ed.) (1980). CRC Handbook of energy utilization in agriculture. (Boca Raton: CRC Press)

- Lynn Ellen Doxon (2001). The Alcohol Fuel Handbook. InfinityPublishing.com. ISBN 978-0-7414-0646-0.

- Gil, C.; Gómez-Cordovés, C. (1986). "Tryptophol content of young wines made from Tempranillo, Garnacha, Viura and Airén grapes". Food Chemistry. 22: 59–65. doi:10.1016/0308-8146(86)90009-9.

- Szlavko, Clara M (1973). "Tryptophol, Tyrosol and Phenylethanol-The Aromatic Higher Alcohols in Beer". Journal of the Institute of Brewing. 79 (4): 283–288. doi:10.1002/j.2050-0416.1973.tb03541.x.

- Ribéreau-Gayon, P.; Sapis, J. C. (2019). "On the presence in wine of tyrosol, tryptophol, phenylethyl alcohol and gamma-butyrolactone, secondary products of alcoholic fermentation". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série D. 261 (8): 1915–1916. PMID 4954284. (Article in French)