Ethel Smyth

Dame Ethel Mary Smyth, DBE (/smaɪθ/, to rhyme with Forsyth;[1] 22 April 1858 – 8 May 1944) was an English composer and a member of the women's suffrage movement. Her compositions include songs, works for piano, chamber music, orchestral works, choral works and operas.

Ethel Smyth DBE | |

|---|---|

Ethel Smyth in 1922 | |

| Born | Ethel Mary Smyth 22 April 1858 |

| Died | 8 May 1944 (aged 86) Woking, England, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Leipzig Conservatory |

| Occupation | Composer and suffragette |

Smyth tended to be marginalised as a ‘woman composer’, as though her work could not be accepted as mainstream. Yet when she produced more delicate compositions, they were criticised for not measuring up to the standard of her male competitors. Nevertheless, she was granted a damehood, the first female composer to be so honoured.

Family background

Ethel Smyth was the fourth of eight children. The youngest was Robert ("Bob") Napier Smyth (1868-1947), who rose to become a Brigadier in the British Army. She was the aunt of Lieutenant General Sir Ralph Eastwood.

She was born in Sidcup, Kent, which is now in the London Borough of Bexley. While April 22 is the actual day of her birth, Smyth habitually stated it was April 23, the day that was celebrated by her family, as they enjoyed the coincidence with William Shakespeare's.[2] Her father, John Hall Smyth, who was a major general in the Royal Artillery, was very much opposed to her making a career in music.[3] She lived at Frimhurst, near Frimley Green[4] for many years, before moving to Hook Heath on the outskirts of Woking.

Musical career

She first studied privately with Alexander Ewing when she was seventeen. He introduced her to the music of Wagner and Berlioz. After a major battle with her father about her plans to devote her life to music, Smyth was allowed to advance her musical education at the Leipzig Conservatory, where she studied composition with Carl Reinecke. She left after a year, however, disillusioned with the low standard of teaching, and continued her music studies privately with Heinrich von Herzogenberg.[3] While she was at the Leipzig Conservatory, she met Dvořák, Grieg and Tchaikovsky. Through Herzogenberg, she also met Clara Schumann and Brahms.[3]

John Singer Sargent

Smyth's extensive body of work includes the Concerto for Violin, Horn and Orchestra and the Mass in D. Her opera The Wreckers is considered by some critics to be the "most important English opera composed during the period between Purcell and Britten."[3] Another of her operas, Der Wald, mounted in 1903, was for more than a century the only opera by a woman composer ever produced at New York's Metropolitan Opera[3][5] (until Kaija Saariaho's L'Amour de loin in December 2016).[6][7]

On 28 May 1928 the nascent BBC broadcast two concerts of Smyth's music, marking her "musical jubilee",[8][9][10] The first comprised chamber music,[9] the second, conducted by Smyth herself, choral works.[8][10] Otherwise, recognition in England came somewhat late for Ethel Smyth, wrote the conductor Leon Botstein at the time he conducted the American Symphony Orchestra's US premiere of The Wreckers in New York on 30 September 2007:[11]

On her seventy-fifth birthday in 1934, under Beecham's direction, her work was celebrated in a festival, the final event of which was held at the Royal Albert Hall in the presence of the Queen. Heartbreakingly, at this moment of long-overdue recognition, the composer was already completely deaf and could hear neither her own music nor the adulation of the crowds.

Her final major work was the hour long vocal symphony The Prison, setting a text by Henry Bennett Brewster. It was first performed in 1931. The first recording was issued by Chandos in 2020.[12] However, she found a new interest in literature and, between 1919 and 1940, she published ten highly successful, mostly autobiographical, books.[3]

Critical reception

Overall, critical reaction to her work was mixed. She was alternately praised and panned for writing music that was considered too masculine for a "lady composer", as critics called her.[13] Eugene Gates writes that

Smyth's music was seldom evaluated as simply the work of a composer among composers, but as that of a "woman composer." This worked to keep her on the margins of the profession, and, coupled with the double standard of sexual aesthetics, also placed her in a double bind. On the one hand, when she composed powerful, rhythmically vital music, it was said that her work lacked feminine charm; on the other, when she produced delicate, melodious compositions, she was accused of not measuring up to the artistic standards of her male colleagues.[14]

Other critics were more favourable: "The composer is a learned musician: it is learning which gives her the power to express her natural inborn sense of humour... Dr. Smyth knows her Mozart and her Sullivan: she has learned how to write conversations in music... [The Boatswain's Mate] is one of the merriest, most tuneful, and most delightful comic operas ever put on the stage."[15]

Involvement with the suffrage movement

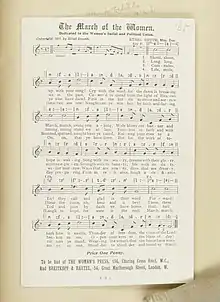

In 1910 Smyth joined the Women's Social and Political Union, a suffrage organization, giving up music for two years to devote herself to the cause, and to accompany its charismatic leader Mrs Pankhurst on many occasions.[16] Her "The March of the Women" (1911) became the anthem of the women's suffrage movement. In 1912 the WSPU's leader, Emmeline Pankhurst, after practising aiming stones at trees near Emerson's home, called on members to break a window in the house of any politician who opposed votes for women. Smyth was one of the 109 members who responded to Pankhurst's call, asking to be sent to attack the home of colonial secretary Harcourt, who had remarked that his wife's beauty and wisdom, if it was present in all women, would have already have won them the vote.[16] Smyth stood half the bail for Helen Craggs, who had been caught on the way to carry out the arson of the leading politician's home.[16] During the stone throwing, Pankhurst and 100 other women were arrested, and she served two months in Holloway Prison.[17][18] When her proponent-friend Thomas Beecham went to visit her there, he found suffragettes marching in the quadrangle and singing, as Smyth leaned out a window conducting the song with a toothbrush.[19] In her writing Female Pipings in Eden Smyth said her experience was of being 'in good company' of united women 'old, young, rich, poor, strong, delicate' putting the idea they were imprisoned for before their personal needs. Smyth had revealed that the prison was infested with cockroaches even in the hospital ward. She was released early from prison due to a medical assessment as being mentally unstable and hysterical. Smyth gave written evidence in the November trial of Mrs. Pankhurst and others for inciting violence to state that she, Smyth, had freely engaged in activism. She continued to correspond with Mrs. Pankhurst and heard of her getting lost finding the safe house provided for her to hide from re-arrest in Scotland, prior to the Glasgow event in March 1914.[16]

Smyth disagreed with the Pankhursts' enthusiasm for joining the war effort, but she did train as a radiographer in Paris, and her fractious friendship with Christabel ended in 1925. She did conduct the Metropolitan Police Band at the unveiling of the statue to Emmeline in London in 1930.[16]

Personal life

Smyth had several passionate affairs in her life, most of them with women. Her philosopher-friend and the librettist of some of her operas, Henry Bennet Brewster, may have been her only male lover. She wrote to him in 1892: "I wonder why it is so much easier for me to love my own sex more passionately than yours. I can't make it out, for I am a very healthy-minded person."[20] Smyth was at one time in love with the married suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst. At age 71, she fell in love with writer Virginia Woolf — herself having worked in the women's suffrage movement[21] — who, both alarmed and amused, said it was "like being caught by a giant crab", but the two became friends.[17] Smyth's relationship with Violet Gordon-Woodhouse is depicted satirically in Roger Scruton's 2005 opera, Violet.

Smyth was actively involved in sport throughout her life. In her youth, she was a keen horse-rider and tennis player. She was a passionate golfer and a member of the ladies' section of Woking Golf Club, near where she lived. After she died and was cremated, her ashes were, as she had requested, scattered in the woods neighbouring the club[22] by her brother Bob.[23]

In recognition of her work as a composer and writer, Smyth was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in 1922,[3][24] becoming the first female composer to be awarded a damehood.[25] Smyth received honorary doctorates in music from the Universities of Durham and Oxford.[22] She died in Woking in 1944 at the age of 86.[26]

Representations

Ethel Smyth featured, under the name of Edith Staines, in E. F. Benson's Dodo books (1893–1921), decades before the quaint musical characters of his more famous Mapp and Lucia series. She "gleefully acknowledged" the portrait, according to Prunella Scales.[27] She was later a model for the fictional Dame Hilda Tablet in the 1950s radio plays of Henry Reed.[28]

She was portrayed by Maureen Pryor in the 1974 BBC television film Shoulder to Shoulder.

Judy Chicago's monumental work of feminist art, The Dinner Party, features a place setting for Ethel Smyth.[29]

In 2018 and 2019 Lucy Stevens has been playing Ethel Smyth on stage at various venues in Britain.[30]

Works

Writings

|

|

- The Memoirs of Ethel Smyth (1987), abridged and edited by Ronald Crichton. Available on 14-day loan at Archive.org (free registration required)

Recordings

- The Boatswain's Mate. Nadine Benjamin, Rebecca Louise Dale, Edward Lee, Ted Schmitz, Jeremy Huw Williams, Simon Wilding, Mark Nathan, Lontano Ensemble, c. Odaline de la Martinez. Retrospect Opera RO001 (two CDs).

- Cello Sonata in C minor (1880): Friedemann Kupsa cello, Anna Silova piano; Lieder und Balladen, Opp. 3 & 4, Three Moods of the Sea (1913): Maarten Koningsberger baritone, Kelvin Grout piano. TRO-CD 01417.[31]

- Complete Piano Works. Liana Șerbescu. CPO 999 327-2.

- Concerto for Violin, Horn and Orchestra. BBC Philharmonic, c. Odaline de la Martinez. Chandos Chan 9449.

- Double Concerto in A for violin, horn and piano (1926): Renate Eggebrecht violin, Franz Draxinger horn, Céline Dutilly piano; Four Songs for mezzo-soprano and chamber ensemble (1907): Melinda Paulsen mezzo, Ethel Smyth ensemble; Three songs for mezzo-soprano and piano (1913): Melinda Paulsen mezzo, Angela Gassenhuber piano. TRO-CD 01405.

- Fete Galante: A Dance Dream Charmian Bedford (soprano), Carolyn Dobbin (mezzo soprano), Mark Milhofer (tenor), Alessandro Fisher (tenor), Felix Kemp (baritone), Simon Wallfisch (baritone), Lontano Ensemble/Odaline de la Martinez. Retrospect Opera RO007

- Mass in D, March of the Women, Scene from The Boatswain's Mate. Eiddwen Harrhy, The Plymouth Music Series, Philip Brunelle. Virgin Classics VC 7 91188-2.

- String Quartet in E Minor and String Quintet op. 1 in E Major. Mannheimer Streichquartett and Joachim Griesheimer. CPO 999 352-2.

- Violin Sonata in A minor, Op. 7, Cello Sonata in A minor, Op. 5, String Quintet in E major, Op. 1, String Quartet in E minor (1912): Renate Eggebrecht, violin, Friedemann Kupsa cello, Céline Dutilly piano, Fanny Mendelssohn Quartet. TRO-CD 01403 (two CDs).

- The Wreckers. Anne-Marie Owens, Justin Lavender, Peter Sidhom, David Wilson-Johnson, Judith Howarth, Anthony Roden, Brian Bannatyne-Scott, Annemarie Sand. Huddersfield Choral Society, BBC Philharmonic, c. Odaline de la Martinez. Conifer Classics. (Re-released by Retrospect Opera, RO004.)

See also

- Norah Smyth - Ethel Smyth's niece and also a notable suffragette

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of Bloomsbury Group people

References

Notes

- S.M. Moon, The Organ Music of Ethel Smyth, Appendix A, 135-137

- Collins. Fuller. Music & History.

- Gates (2013), pp. 1 – 9

- Jebens and Cansdale, p. 4

- Yohalem, John, "A Woman's Opera at the Met: Ethel Smyth’s Der Wald in New York", The Metropolitan Opera Archives

- Cooper, Michael (17 February 2016). "Met to Stage Its First Opera by a Woman Since 1903". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- Tommasini, Anthony (2 December 2016), "Review: A Newly Relevant 'L'Amour de Loin' at the Met", The New York Times, retrieved 2 December 2016

- "New Music" (PDF). BBC Hand Book 1929. BBC. 1928. p. 72.

- "Ethel Smyth Jubilee Concert". The Radio Times (242). 18 May 1928. p. 11. ISSN 0033-8060. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Ethel Smyth Jubilee Concert". The Radio Times (242). 18 May 1928. p. 10. ISSN 0033-8060. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- Leon Botstein, The Wreckers on americansymphony.org Retrieved 1 March 2013

- Allen, David. 'Ethel Smyth, a Composer Long Unheard, Is Recorded Anew' in The New York Times, 11 August 2020

- Lumsden (2015). ""The Music Between Us": Ethel Smyth, Emmeline Pankhurst, and "Possession"". Feminist Studies. 41 (2): 335–370. doi:10.15767/feministstudies.41.2.335. JSTOR 10.15767/feministstudies.41.2.335.

- Gates (2006), "Damned If You Do and Damned If You Don't"

- The Illustrated London News, 18 March 1922, p. 386, in reference to a revival of her opera "The Boatswain's Mate"

- Atkinson, Diane (2018). Rise up, women! : the remarkable lives of the suffragettes. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 247, 292, 303, 318, 324, 464, 560. ISBN 9781408844045. OCLC 1016848621.

- Abromeit, Kathleen A., "Ethel Smyth, The Wreckers, and Sir Thomas Beecham", The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 73, issue 2, 1989, pp. 196–211. By subscription or payment on JSTOR

- "Brooklyn Museum: Ethel Smyth". www.brooklynmuseum.org. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- Beecham, Thomas (1958). "Dame Ethel Smyth (1858–1944)". The Musical Times. 99 (1385): 363–365. JSTOR 936486.

- St. John, p. ?

- Wiley, Christopher (2004). "'When a Woman Speaks the Truth about Her Body': Ethel Smyth, Virginia Woolf, and the Challenges of Lesbian Auto/Biography" (PDF). Music & Letters. 85 (3): 388–414. doi:10.1093/ml/85.3.388. JSTOR 3526233. S2CID 23067752. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2020.

- Five facts about Dame Ethel Smyth Oxford University Press Blog. (by Christopher Wiley)

- Ethel Smyth Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 23 May 2016

- "No. 32563". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 1921. p. 10716.

- heraldica. Retrieved 14 Mar 2016

- "Dame Ethel Smyth (1858 – 1944)". Exploring Surrey's Past.

- Scales, introduction to Benson (1986)

- Hold, Trevor; Quartet, Fanny Mendelssohn; Dutilly, Celine; Paulsen, Melinda; Eggebrecht-Kupsa, Renate; Draxinger, Franz; Ensemble, Ethel Smyth (January 1993). "CD Reviews". The Musical Times. Musical Times Publications Ltd. 134 (1799): 43. doi:10.2307/1002644. JSTOR 1002644.

- "Ethel Smyth". The Dinner Party: Place Settings. Brooklyn Museum.

- "2019". 3 January 2018.

- "Troubadisc website". Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

Cited sources

- "Music and History". musicand history.com. Archived from the original on 23 November 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- Benson, E.F. (1986), Dodo: An Omnibus. London: Hogarth Press, 1986 ISBN 0701206969 ISBN 0-7012-0696-9

- Collis, Louise. Impetuous Heart: The Story of Ethel Smyth. London: William Kimber, 1984. ISBN 0-7183-0543-4

- Fuller, Sophie. "Smyth, Dame Ethel". Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000026038 (inactive 18 January 2021). Retrieved 29 October 2020.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Gates, Eugene (2006), "Damned If You Do and Damned If You Don't: Sexual Aesthetics and the Music of Dame Ethel Smyth", Kapralova Society Journal 4, no. 1, 2006: 1–5.

- Gates, Eugene (2013), "Dame Ethel Smyth: Pioneer of English Opera." Kapralova Society Journal 11, no. 1 (2013): 1–9.

- Jebens, Dieter and R. Cansdale (2004), Guide to the Basingstoke Canal. Basingstoke Canal Authority and the Surrey and Hampshire Canal Society, 2004. (2nd Edition)

- St. John, Christopher (1959), Ethel Smyth: A Biography. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1959.

Further reading

- Anderson, Gwen, Ethel Smyth, London: Cecil Woolf, 1997. ISBN 189796790X ISBN 1-897967-90-X

- Bartsch, Cornelia, Rebecca Grotjahn, and Melanie Unseld. Felsensprengerin, Brückenbauerin, Wegbereiterin: Die Komponistin Ethel Smyth. Rock Blaster, Bridge Builder, Road Paver: The Composer Ethel Smyth. Allitera (2010) ISBN 978-3-86906-068-2

- Crichton, Ronald. The Memoirs of Ethel Smyth. London: Viking Press, 1987. ISBN 0670806552 ISBN 0-670-80655-2

- Kertesz, Elizabeth Jane, Issues in the critical reception of Ethel Smyth’s Mass and first four operas in England and Germany, PhD Dissertation, Melbourne: University of Melbourne on unimelb.edu.au

- Rieger, Eva (editor). A Stormy Winter: Memories of a Pugnacious English Composer. (Autobiography of Ethel Smyth) (Published in German as Ein stürmischer Winter. Erinnerungen einer streitbaren englischen Komponistin.) Kassel: Bärenreiter-Verlag, 1988.

- Stone, Caroline E.M. Another Side of Ethel Smyth: Letters to her Great-Niece, Elizabeth Mary Williamson. Kennedy & Boyd, 2018. ISBN 9781849211673

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article about "Ethel Smyth". |

- Free scores by Ethel Smyth at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Online books, and library resources in your library and in other libraries by Ethel Smyth

- Library resources in your library and in other libraries about Ethel Smyth

- LiederNet Archive

- Dame Ethel Smyth: Pioneer of English Opera – by Eugene Gates, Kapralova Society Journal.

- Ethel Smyth – by Valarie Morris, Sandscape Publications.

- Ethel Mary Smyth letter from the Special Collections and University Archives Department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro

- Ethel Mary Smyth letter 2 from the Special Collections and University Archives Department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro

- Dame Ethel Mary Smyth (1858–1944), Composer and writer (National Portrait Gallery)

- "Archival material relating to Ethel Smyth". UK National Archives.

- Works by or about Ethel Smyth at Internet Archive

- Dame Ethel Smyth: Composer, suffragette, sportswoman and resident of Woking

- Retrospect Opera