Face card

In a deck of playing cards, the term face card (US) or court card (British and US)[1] is generally used to describe a card that depicts a person as opposed to the pip cards. They are also known as picture cards, or until the early 20th century, coat cards.

History

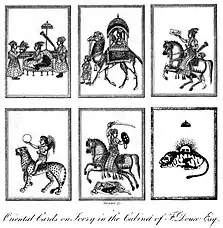

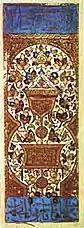

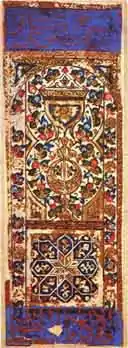

While playing cards were invented in China, Chinese playing cards do not have a concept of face cards. When playing cards arrived in Iran, the Persians created the first face cards.The best preserved deck is located in the Topkapı Palace. To avoid idolatry,[2] the cards did not depict human faces and instead featured abstract designs or calligraphy for the malik (king), nā'ib malik (viceroy or deputy king) and thānī nā'ib (second or under-deputy).[3] It is possible that the Topkapı deck, a custom made luxury item used for display, does not represent the cards played by commoners. There are fragments of what may be Mamluk court cards from cheaper decks showing human figures which may explain why seated kings and mounted men appear in both Indo-Persian and European cards. Both Mamluk and modern European decks include three face cards per suit, or twelve face cards in a deck of four suits.[4][5]

The third court card may have had a special role to play since the Spanish, French, and Italians called the newly introduced cards naipe, nahipi, and naibi respectively as opposed to their Arabic name of Kanjifah. In a 1377 description of cards by John of Rheinfelden, the most common decks were structurally the same as the modern 52-card deck.[6] Each suit contained a seated king and two marshals, one holding the suit symbol upwards while the other downwards. The marshals correspond to the Ober and Unter ranks in modern-day German and Swiss playing cards. As marshals were cavalry commanders, both ranks may have been mounted unlike their modern counterparts. Less popular decks included ones in which two kings were replaced with queens, all the kings replaced by queens, queens and maids added so as to make 15 cards per suit, and 5 or 6 suited decks with only the kings and two marshal ranks.[5]

In Italy and Spain, the Unter and Ober were replaced by the standing Knave and the mounted Knight before 1390, perhaps to make them more visually distinguishable. The Spanish rank of Sota means "under". In 15th-century France, the knight was dropped in favour of the queen. The 15th-century Italian game of trionfi, which later became known as tarot, also added queens. The Cary-Yale deck had the most with six ranks: king, queen, knight, mounted lady, knave, and damsel or maid for a total of 24. It is unlikely that the Cary-Yale deck was designed for a game in mind as it was an expensive wedding gift and was probably never played. Standing kings are a Spanish innovation which was copied by the French.

Throughout most of their history, face cards were not reversible. Players may accidentally reveal that they hold a face card if they flip them right-side up. During the 18th century, Trappola and Tarocco Bolognese decks became the first to be reversible. The trend towards double-headed cards continued throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Some patterns resisted the innovation, most notably Spanish-suited decks where full figured courts remain dominant.

Cards

Current playing cards are structured as follows:

- German and Swiss playing cards have three male face cards per suit, Unter/Under (a lower-class man or soldier), Ober (a higher ranking man), and König (a seated King).

- Italian and Spanish playing cards have the Fante or Sota (Knave, a younger man standing), Cavallo or Caballo (Knight or Cavalier, a man sitting on a horse) and Re or Rey (King, wearing a crown). Italian suited kings are seated while Spanish suited kings stand. A few Spanish suited patterns replace male knaves with female counterparts.

- French playing cards replaced the middle male with the Queen so it became Knave or "Jack", Queen, and King. French suited Kings stand.

- French and Latin tarot decks have four face cards per suit. Their order is Knave, Knight, Queen, and King for a total of 16 face cards. Figures appearing on tarot trumps are not considered to be face cards.

While modern decks of playing cards may contain one or more Jokers depicting a person (such as a jester or clown), Jokers are not normally considered to be face cards. The earliest Jokers, known as Best Bowers, did not depict people until the late 1860s.

References

- Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1855). "On False Etymologies". Transactions of the Philological Society (6): 71.

- Origin of playing cards by Copag. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- Jensen, K. The Mamluk cards Archived 2015-04-26 at the Wayback Machine at Manteia. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- Gjerde, Tor. Mamluk cards at old.no. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- Dummett, Michael; Mann, Sylvia (1980). The Game of Tarot. London: Duckworth. pp. 10–64.

- Johannes of Rheinfelden, 1377 at trionfi.com. Retrieved 18 February 2017.