Falash Mura

Falash Mura is the name given to those of the Beta Israel community in Ethiopia who converted to Christianity as a consequence of proselytization during the 19th and 20th centuries. This term consists of Beta Israel who did not adhere to Israelite law, as well as converts to Christianity, who did so either voluntarily or who were forced to do so.

There are approximately 8,200 Falash Mura living in Ethiopia today. The Israeli government, in 2018, approved a plan to allow 1,000 of them to move to Israel.

They derive from the Beta Israel of Ethiopia, however, the Falash Mura converted to Christianity and are not considered under the Israeli Law of Return. Some have made it to Israel but many still reside in camps in Gondar and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, waiting their status for Aliyah. Some Falash Mura have reverted to Judaism.[1]

Terminology

The original term that the Beta Israel gave to the converts was "Faras Muqra" ("horse of the raven") in which the word "horse" refers to the converts and the word "raven" refers to the missionary Martin Flad who used to wear black clothes.[2] This term derived the additional names Falas Muqra, Faras Mura and Falas Mura. In Hebrew the term "Falash Mura" (or "Falashmura") is probably a result of confusion over the use of the term "Faras Muqra" and its derivatives and on the basis of false cognate it was given the Hebrew meaning Falashim Mumarim ("converted Falashas").

In Ge'ez, the original language of the Bet Israel Falasha means "cut off". This term was coined due to the people of Bet Israel's resistance in converting to Christianity, as Judaism was the old religion of Ethiopia.

The actual term "Falash Mura" has no clear origin. It is believed that the term may come from the Agau and means "someone who changes their faith."[3]

History

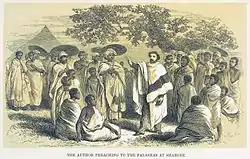

In 1860, Henry Aaron Stern, a Jewish convert to Christianity, traveled to Ethiopia and in an attempt to convert the Beta Israel community to Christianity.

Conversion to Christianity

For years, Ethiopian Jews were unable to own land and were often persecuted by the Christian majority of Ethiopia. Ethiopian Jews were afraid to touch non-Jews because they believed non-Jews were not pure, which also ostracized them from their Christian neighbors. For this reason, many Ethiopian Jews converted to Christianity to seek a better life in Ethiopia. The Jewish Agency's Ethiopia emissary, Asher Seyum, says the Falash Mura "converted in the 19th and 20th century, when Jewish relations with Christian rulers soured. Regardless, many kept ties with their Jewish brethren and were never fully accepted into the Christian communities. When word spread about the aliyah, many thousands of Falash Mura left their villages for Gondar and Addis Ababa, assuming they counted."[4]

In the Achefer woreda of the Mirab Gojjam Zone, roughly 1,000–2,000 families of Beta Israel were found.[5] There may be other such regions in Ethiopia with significant Jewish enclaves, which would raise the total population to more than 50,000 people.[6]

Return to Judaism

The Falash Mura did not refer to themselves as members of the Beta Israel, the name for the Ethiopian Jewish community, until after the first wave of immigration to Israel. Beta Israel by ancestry, the Falash Mura believe they have just as much of a right to return to Israel as the Beta Israel themselves. Rabbi Ovadiah Yosef, a major player in the first wave of Beta Israel immigration to Israel, declared in 2002 that the Falash Mura had converted out of fear and persecution and therefore should be considered Jews.[3]

Aliyah to Israel

Today, Falash Mura who move to Israel must undergo conversion on arrival, making it increasingly more difficult for them to get situated into Israeli society. The Beta Israel who immigrated and made Aliyah through Operation Moses and Operation Solomon were not required to undergo conversion because they were accepted as Jews under the Law of Return.

On February 16, 2003, the Israeli government applied Resolution 2958 to the Falash Mura, which grants maternal descendants of Beta Israel the right to immigrate to Israel under the Israeli Law of Return and to obtain citizenship if they convert to Judaism.[7]

Controversy

Today, both Israeli and Ethiopian groups dispute the Falash Mura's religious and political status.[4] The Israeli government fears that these people are just using Judaism as an excuse to leave Ethiopia in efforts to improve their lives in a new country. Right-wing member of the Israeli Knesset Bezalel Smotrich was quoted saying, "This practice will develop into a demand to bring more and more family members not included in the Law of Return. It will open the door to an endless extension of a family chain from all over the world," he wrote, according to Kan. "How can the state explain in the High Court the distinction it makes between the Falashmura and the rest of the world?"[8] Although the government has threatened to stop all efforts to bring these people to Israel, they have still continued to address the issue. In 2018, The Israeli government allowed 1,000 Falash Mura to immigrate to Israel. However, members of the Ethiopian community say the process for immigration approval is poorly executed and inaccurate, dividing families. At least 80 percent of the tribe members in Ethiopia say they have first-degree relatives living in Israel, and some have been waiting for 20 years to immigrate.[8]

Affiliated groups

References

- "The Falash Mura". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- Abbink, Gerrit Jan (1984). The Falashas in Ethiopia and Israel: the problem of ethnic assimilation. Institute for Cultural and Social Anthropology. pp. 81–82. Can also be found here and archived here.

- "The Falash Mura". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- Berger, Miriam (August 9, 2013). "The Last Jews of Ethiopia". ProQuest 1474180933. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) Can also be found here and archived here. - Abbink, Jon (1990). "The Enigma of Beta Esra'el Ethnogenesis. An Anthro-Historical Study". Cahiers d'études africaines. 30 (120): 397–449. doi:10.3406/cea.1990.1592. ISSN 0008-0055.

- "The Plight of Ethiopian Jews". www.culturalsurvival.org. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- "Falashmura aliyah - follow-up report" (PDF) (in Hebrew). Israeli Association for Ethiopian Jews. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2009.

- "Cabinet approves immigration of 1,000 Ethiopian Falashmura to Israel". Times of Israel. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

Further reading

- Samuel Gobat, Journal of a three years' residence in Abyssinia: in furtherance of the objects of the Church Missionary Society, Hatchard & Son; and Seeley & Sons, 1834

- Henry Aaron Stern, Wanderings among the Falashas in Abyssinia: Together with Descriptions of the Country and Its Various Inhabitants, Wertheim, Macintosh, and Hunt, 1862

- Johann Martin Flad, The Falashas (Jews) of Abyssinia, W. Macintosh, 1869

- Eric Payne, Ethiopian Jews: the story of a mission, Olive Press, 1972

- Steven Kaplan, "The Beta Israel (Falasha) Encounter with Protestant Missionaries: 1860-1905", Jewish Social Studies 49 (1), 1987, pp. 27–42

- Michael Corinaldi, Jewish identity: the case of Ethiopian Jewry, Magnes Press, 1998, ISBN 9652239933

- Daniel Frieilmann, "The Case of the Falas Mura" in Tudor Parfitt & Emanuela Trevisan Semi (Editors), The Beta Israel in Ethiopia and Israel: Studies on Ethiopian Jews, Routledge, 1999, ISBN 9780700710928

- Don Seeman, "The Question of Kinship: Bodies and Narratives in the Beta Israel-European Encounter (1860-1920)", Journal of Religion in Africa, Vol. 30, Fasc. 1 (Feb., 2000), pp. 86–120

- Emanuela Trevisan Semi, "The Conversion of the Beta Israel in Ethiopia: A Reversible "Rite of Passage"", Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 1 (1), 2002, pp. 90–103

- Don Seeman, One People, One Blood: Ethiopian-Israelis and the Return to Judaism, Rutgers University Press, 2010, ISBN 9780813549361