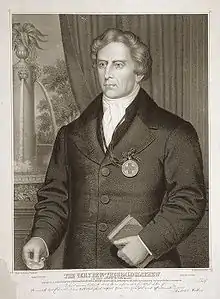

Father Mathew

Theobald Mathew (10 October 1790 – 8 December 1856)[1] was an Irish Catholic priest and teetotalist reformer, popularly known as Father Mathew. He was born at Thomastown, near Golden, County Tipperary, on 10 October 1790, to James Mathew and his wife Anne, daughter of George Whyte, of Cappaghwhyte.[2] Of the family of the Earls Landaff (his father, James, was first cousin of Thomas Mathew, father of the first earl),[3] he was a kinsman of the clergyman Arnold Mathew.[4][5][6]

Theobald Mathew | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 10 October 1790 Thomastown, County Tipperary, Ireland |

| Died | 8 December 1856 (aged 66) Queenstown, County Cork, Ireland |

| Religion | Christianity (Roman Catholic) |

| Church | Latin Church |

He received his schooling in Kilkenny, then moved for a short time to Maynooth.[7] From 1808 to 1814 he studied in Dublin, where in the latter year he was ordained to the priesthood. Having entered the Capuchin order, after a brief period of service at Kilkenny, he joined the mission in Cork.[8]

Statues of Mathew stand on St. Patrick's Street, Cork, by J. H. Foley (1864), and on O'Connell Street, Dublin, by Mary Redmond (1893).[9] There is a Fr. Mathew Bridge in Limerick City, named after the temperance reformer when it was rebuilt between 1844 and 1846.[10] The Capuchin church in Cork, Holy Trinity, stands on Father Mathew Quay and was commissioned by him.[11]

Total Abstinence Society

The movement with which his name is associated began on 10 April 1838 with the establishment of the "Cork Total Abstinence Society", which in less than nine months enrolled no fewer than 150,000 names. It rapidly spread to Limerick and elsewhere, and some idea of its popularity may be formed from the fact that at Nenagh 20,000 persons are said to have taken the pledge in one day, 100,000 at Galway in two days, and 70,000 in Dublin in five days. At its height, just before the Great Famine of 1845–49, his movement enrolled some 3 million people, or more than half of the adult population of Ireland. In 1844, he visited Liverpool, Manchester and London with almost equal success.[12]

A biography, written shortly after his death, credits Mathew's work with a reduction in Irish crime figures of the era:

The number of homicides, which was 247 in 1838, was only 105 in 1841. There were 91 cases of 'firing at the person' reported in 1837, and but 66 in 1841. The 'assaults on police' were 91 in 1837, and but 58 in 1841. Incendiary fires, which were as many as 459 in 1838, were 390 in 1841. Robberies, thus specially reported, diminished from 725 in 1837, to 257 in 1841. The decrease in cases of 'robbery of arms' was most significant; from being 246 in 1837, they were but 111 in 1841. The offence of 'appearing in arms' showed a favourable diminution, falling from 110 in 1837, to 66 in 1841. The effect of sobriety on 'faction fights' was equally remarkable. There were 20 of such cases in 1839, and 8 in 1841. The dangerous offence of 'rescuing prisoners', which was represented by 34 in 1837, had no return in 1841!

The number committed to jail fell from 12,049 in 1839 to 9,875 by 1845. Sentences of death fell from 66 in 1839 to 14 in 1846, and transportations fell from 916 to 504 over the same period.[13]

In the United States

Mathew visited the United States in 1849, returning in 1851.[12] While there, he found himself at the center of the Abolitionist debate. Many of his hosts, including John Hughes, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of New York, were anti-abolitionists[15] and wanted assurances that Mathew would not stray outside his remit of battling alcohol consumption. But Mathew had signed a petition (along with 60,000 Irish people, including Daniel O'Connell) encouraging the Irish in the US not to partake in slavery in 1841 during Charles Lenox Remond's tour of Ireland.[16]

In order to avoid upsetting these anti-abolitionist friends in the US, he snubbed an invitation to publicly condemn chattel slavery, sacrificing his friendship with that movement. He defended his position by pointing out that there was nothing in the scripture that prohibited slavery. He was condemned by many on the abolitionist side, including the former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass who had received the pledge from Mathew in Cork in 1845. Douglass felt "grieved, humbled and mortified" by Mathew's decision to ignore slavery while campaigning in the US and "wondered how being a Catholic priest should inhibit him from denouncing the sin of slavery as much as the sin of intemperance."[17] Douglass felt it was his duty to now "denounce and expose the conduct of Father Mathew".[18]

Death

Mathew died on 8 December 1856 in Queenstown, County Cork (present-day Cobh),[19] and was interred in St. Joseph's Cemetery, Cork, a cemetery which he had himself established.[20]

Father Mathew's Tower

In 1842, at his own expense, landowner William O'Connor built a castellated neo-Gothic stone tower to commemorate Father Mathew on what was then called Mount Patrick and is now known as Tower Hill in Glounthaune which is a hamlet approximately ten miles from the city of Cork. The tower is still extant and has since been converted into a private residence while retaining many of its original features including a life-sized statue of Father Mathew that is still located in the tower's garden. Around 2014 the refurbished and modernized tower was sold for approximately one million pounds. For a detailed eyewitness description of the tower in the summer of 1848, see Asenath Nicholson's Annals of the Famine in Ireland in 1847, 1848 and 1849 Ulsterbooks, 2017, pp. 184–193.

Nicholson also discusses Father Mathew in great detail in Annals on pp. 212–214.

See also

References

Footnotes

- Curtin-Kelly 2015, pp. 21, 29.

- The Catholic Encyclopaedia, ed. Charles George Herbermann, Universal Knowledge Foundation, 1913, p. 47

- Burke's Landed Gentry of Ireland, 1976, Mathew pedigree

- The History and Antiquities of Glamorganshire and Its Families, Thomas Nicholas, Longmans, Green & Co., 1874, p. 120

- "Estate: Mathew (Thomastown)". Landed Estates Database. National University of Ireland Galway. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Genealogy of the Earls of Landaff, of Thomastown, County Tipperary, Murray Alexander Mathew, Capuchin Franciscan Friars, Church Street

- Mathew 1894, p. 32.

- Augustine 1911.

- Irish Times. 28 October 2010. p. 17.

- "Edward Uzuld". Dictionary of Irish Architects. Irish Architectural Archive.

- "1889 – Holy Trinity & Capuchin Monastery, Cork". Archiseek. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Maguire 1863, pp. 200–201.

- Fegan, Joyce (27 November 2014). "124-Year-Old Fr Mathew Statue Needs a New Home Due to Luas". Independent.ie. Dublin. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "Archbishop John J. Hughes (1797–1863)". Mr. Lincoln and New York. Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- Dooley 1998, pp. 10–11.

- Kerrigan 1991.

- Hogan, Liam (29 September 2014). "'Oh What a Transition It Was to Be Changed from the State of a Slave to That of a Free Man!' Frederick Douglass's Journey from Slavery to Limerick". The Irish Story. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- Augustine 1911, p. 47; Mathew 1894, p. 32.

- Thomas, Fr (1902). Summarised Life of the great Temperance Apostle : Fr. Theobald Mathew. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Cork, Ireland : Guy and Co. Ltd. pp. 86.

Bibliography

- Augustine, Father (1911). . In Herbermann, Charles G.; Pace, Edward A.; Pallen, Condé B.; Shahan, Thomas J.; Wynne, John J. (eds.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 10. New York: Encyclopedia Press (published 1913). pp. 47–48.

This article incorporates text from this public-domain publication. - Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 886.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curtin-Kelly, Patricia (2015). An Ornament to the City: Holy Trinity Church and the Capuchin Order. Dublin: The History Press Ireland. ISBN 978-1-84588-861-9.

- Dooley, Brian (1998). Black and Green: The Fight for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland & Black America. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-1295-8.

- Kerrigan, Colm (1991). "Irish Temperance and US Anti-Slavery: Father Mathew and the Abolitionists". History Workshop Journal. 31 (1): 105–119. doi:10.1093/hwj/31.1.105. ISSN 1477-4569.

- Maguire, John Francis (1863). Father Mathew: A Biography. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Mathew, James Charles (1894). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 37. New York: Macmillan and Co. pp. 32–34.

Further reading

- "19th Century". Capuchin Friars of Kilkenny. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Birmingham, James (1841) [1840]. Morris, P. H. (ed.). A Memoir of the Very Rev. Theobald Mathew: with an Account of the Rise and Progress of Temperance in Ireland (2nd ed.). New York: Alexander V. Blake.

- Bradbury, Osgood (1844). Life of Theobald Mathew, the Great Apostle of Temperance. Boston, Massachusetts: J. N. Bradley & Co. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Doherty, John J. (2008). Frederick Douglass and the White Negro (motion picture).

- Foote, Henry S. (1849). Rev. Theobald Mathew: Remarks of Hon. H.S. Foote, of Mississippi in the Senate, December 10, 1849, on the Resolution to Permit the Rev. Theobald Mathew to Sit Within the Bar of the Senate. Washington: Congressional Globe Office.

- Henshaw, Joshua Sidney (1849). The Life and Mission of the Rev. Theobald Mathew. New York: J. C. Riker.

- Ireland, John (1890). "Theobald Mathew". Donahoe's Magazine. Vol. 24 no. 5. Boston, Massachusetts: Thomas B. Noonan & Company. pp. 465–470.

- Mathew, Theobald (1840). An Accurate Report of the Very Rev. Theobald Mathew: In Dublin, in the Cause of Temperance ... (sermon). Dublin: R. Grace. OCLC 39517820.

- Rogers, Patrick (1943). Father Theobald Mathew, Apostle of Temperance. Dublin: Browne and Nolan.

- Thomas, Father (1902). Summarised Life of the Great Temperance Apostle Fr. Theobald Mathew. Cork, Ireland: Guy and Co. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Townend, Paul A. (2002). Father Mathew, Temperance, and Irish Identity. Dublin: Irish Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-7165-2737-4.

External links

- Fr. Theobald Mathew:Research and Commemorative Papers, Irish Capuchin Archives (PDF)