Fernand Léger

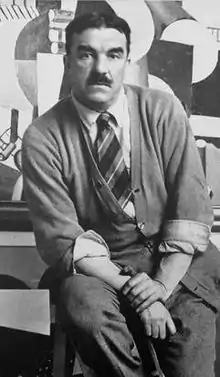

Joseph Fernand Henri Léger (French: [leʒe]; February 4, 1881 – August 17, 1955) was a French painter, sculptor, and filmmaker. In his early works he created a personal form of cubism (known as "tubism") which he gradually modified into a more figurative, populist style. His boldly simplified treatment of modern subject matter has caused him to be regarded as a forerunner of pop art.

Fernand Léger | |

|---|---|

Fernand Léger, c. 1916 | |

| Born | February 4, 1881 |

| Died | August 17, 1955 (aged 74) Gif-sur-Yvette, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painting, printmaking and filmmaking |

| Movement | Cubism Modernism |

Biography

Léger was born in Argentan, Orne, Lower Normandy, where his father raised cattle. Fernand Léger initially trained as an architect from 1897 to 1899, before moving in 1900 to Paris, where he supported himself as an architectural draftsman. After military service in Versailles, Yvelines, in 1902–1903, he enrolled at the School of Decorative Arts after his application to the École des Beaux-Arts was rejected. He nevertheless attended the Beaux-Arts as a non-enrolled student, spending what he described as "three empty and useless years" studying with Gérôme and others, while also studying at the Académie Julian.[1][2] He began to work seriously as a painter only at the age of 25. At this point his work showed the influence of impressionism, as seen in Le Jardin de ma mère (My Mother's Garden) of 1905, one of the few paintings from this period that he did not later destroy. A new emphasis on drawing and geometry appeared in Léger's work after he saw the Cézanne retrospective at the Salon d'Automne in 1907.[3]

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_120_x_170_cm%252C_Kr%C3%B6ller-M%C3%BCller_Museum.jpg.webp)

1909–1914

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_129.2_x_96.5_cm%252C_Solomon_R._Guggenheim_Museum%252C_New_York..jpg.webp)

%252C_oil_on_burlap%252C_128.6_x_95.9_cm%252C_Solomon_R._Guggenheim_Museum%252C_New_York%252C_Solomon_R._Guggenheim.jpg.webp)

In 1909 he moved to Montparnasse and met Alexander Archipenko, Jacques Lipchitz, Marc Chagall, Joseph Csaky and Robert Delaunay.

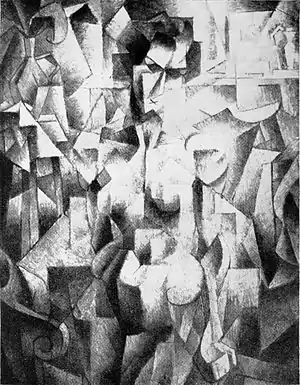

In 1910 he exhibited at the Salon d'Automne in the same room (salle VIII) as Jean Metzinger and Henri Le Fauconnier. In his major painting of this period, Nudes in the Forest, Léger displays a personal form of Cubism that his critics termed "Tubism" for its emphasis on cylindrical forms.[4]

In 1911 the hanging committee of the Salon des Indépendants placed together the painters identified as 'Cubists'. Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Le Fauconnier, Delaunay and Léger were responsible for revealing Cubism to the general public for the first time as an organized group.

The following year he again exhibited at the Salon d'Automne and Indépendants with the Cubists, and joined with several artists, including Le Fauconnier, Metzinger, Gleizes, Francis Picabia and the Duchamp brothers, Jacques Villon, Raymond Duchamp-Villon and Marcel Duchamp to form the Puteaux Group—also called the Section d'Or (The Golden Section).

Léger's paintings, from then until 1914, became increasingly abstract. Their tubular, conical, and cubed forms are laconically rendered in rough patches of primary colors plus green, black and white, as seen in the series of paintings with the title Contrasting Forms. Léger made no use of the collage technique pioneered by Braque and Picasso.[5]

1914–1920

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_130_x_97_cm%252C_Kunstsammlung_Nordrhein-Westfalen%252C_D%C3%B9sseldorf.jpg.webp)

Léger's experiences in World War I had a significant effect on his work. Mobilized in August 1914 for service in the French Army, he spent two years at the front in Argonne.[4] He produced many sketches of artillery pieces, airplanes, and fellow soldiers while in the trenches, and painted Soldier with a Pipe (1916) while on furlough. In September 1916 he almost died after a mustard gas attack by the German troops at Verdun. During a period of convalescence in Villepinte he painted The Card Players (1917), a canvas whose robot-like, monstrous figures reflect the ambivalence of his experience of war. As he explained:

...I was stunned by the sight of the breech of a 75 millimeter in the sunlight. It was the magic of light on the white metal. That's all it took for me to forget the abstract art of 1912–1913. The crudeness, variety, humor, and downright perfection of certain men around me, their precise sense of utilitarian reality and its application in the midst of the life-and-death drama we were in ... made me want to paint in slang with all its color and mobility.[6]

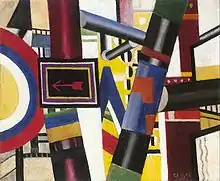

This work marked the beginning of his "mechanical period", during which the figures and objects he painted were characterized by sleekly rendered tubular and machine-like forms. Starting in 1918, he also produced the first paintings in the Disk series, in which disks suggestive of traffic lights figure prominently.[7] In December 1919 he married Jeanne-Augustine Lohy, and in 1920 he met Le Corbusier, who would remain a lifelong friend.

1920s

The "mechanical" works Léger painted in the 1920s, in their formal clarity as well as in their subject matter—the mother and child, the female nude, figures in an ordered landscape—are typical of the postwar "return to order" in the arts, and link him to the tradition of French figurative painting represented by Poussin and Corot.[8] In his paysages animés (animated landscapes) of 1921, figures and animals exist harmoniously in landscapes made up of streamlined forms. The frontal compositions, firm contours, and smoothly blended colors of these paintings frequently recall the works of Henri Rousseau, an artist Léger greatly admired and whom he had met in 1909.

They also share traits with the work of Le Corbusier and Amédée Ozenfant who together had founded Purism, a style intended as a rational, mathematically based corrective to the impulsiveness of cubism. Combining the classical with the modern, Léger's Nude on a Red Background (1927) depicts a monumental, expressionless woman, machinelike in form and color. His still life compositions from this period are dominated by stable, interlocking rectangular formations in vertical and horizontal orientation. The Siphon of 1924, a still life based on an advertisement in the popular press for the aperitif Campari, represents the high-water mark of the Purist aesthetic in Léger's work.[9] Its balanced composition and fluted shapes suggestive of classical columns are brought together with a quasi-cinematic close-up of a hand holding a bottle.

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_171.2_x_240.9_cm%252C_Kunstmuseum_Basel.jpg.webp)

As an enthusiast of the modern, Léger was greatly attracted to cinema, and for a time he considered giving up painting for filmmaking.[10] In 1923–24 he designed the set for the laboratory scene in Marcel L'Herbier's L'Inhumaine (The Inhuman One). In 1924, in collaboration with Dudley Murphy, George Antheil, and Man Ray, Léger produced and directed the iconic and Futurism-influenced film Ballet Mécanique (Mechanical Ballet). Neither abstract nor narrative, it is a series of images of a woman's lips and teeth, close-up shots of ordinary objects, and repeated images of human activities and machines in rhythmic movement.[11]

In collaboration with Amédée Ozenfant he established the Académie Moderne, a free school where he taught from 1924, with Alexandra Exter and Marie Laurencin. He produced the first of his "mural paintings", influenced by Le Corbusier's theories, in 1925. Intended to be incorporated into polychrome architecture, they are among his most abstract paintings, featuring flat areas of color that appear to advance or recede.[12]

1930s

Starting in 1927, the character of Léger's work gradually changed as organic and irregular forms assumed greater importance.[13] The figural style that emerged in the 1930s is fully displayed in the Two Sisters of 1935, and in several versions of Adam and Eve.[14] With characteristic humor, he portrayed Adam in a striped bathing suit, or sporting a tattoo.

In 1931, Léger made his first visit to the United States, where he traveled to New York City and Chicago.[15] In 1935, the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented an exhibition of his work. In 1938, Léger was commissioned to decorate Nelson Rockefeller's apartment.[16]

1940s

During World War II Léger lived in the United States. He taught at Yale University, and found inspiration for a new series of paintings in the novel sight of industrial refuse in the landscape. The shock of juxtaposed natural forms and mechanical elements, the "tons of abandoned machines with flowers cropping up from within, and birds perching on top of them" exemplified what he called the "law of contrast".[17] His enthusiasm for such contrasts resulted in such works as The Tree in the Ladder of 1943–44, and Romantic Landscape of 1946. Reprising a composition of 1930, he painted Three Musicians (Museum of Modern Art, New York) in 1944. Reminiscent of Rousseau in its folk-like character, the painting exploits the law of contrasts in its juxtaposition of the three men and their instruments.[18]

During his American sojourn, Léger began making paintings in which freely arranged bands of color are juxtaposed with figures and objects outlined in black. Léger credited the neon lights of New York City as the source of this innovation: "I was struck by the neon advertisements flashing all over Broadway. You are there, you talk to someone, and all of a sudden he turns blue. Then the color fades—another one comes and turns him red or yellow."[19]

Upon his return to France in 1945, he joined the Communist Party.[20] During this period his work became less abstract, and he produced many monumental figure compositions depicting scenes of popular life featuring acrobats, builders, divers, and country outings. Art historian Charlotta Kotik has written that Léger's "determination to depict the common man, as well as to create for him, was a result of socialist theories widespread among the avant-garde both before and after World War II. However, Léger's social conscience was not that of a fierce Marxist, but of a passionate humanist".[21] His varied projects included book illustrations, murals, stained-glass windows, mosaics, polychrome ceramic sculptures, and set and costume designs.

1950s

After the death of Leger's wife Jeanne-Augustine Lohy in 1950, Léger married Nadia Khodossevitch in 1952. In his final years he lectured in Bern, designed mosaics and stained-glass windows for the Central University of Venezuela in Caracas, Venezuela, and painted Country Outing, The Camper, and the series The Big Parade. In 1954 he began a project for a mosaic for the São Paulo Opera, which he would not live to finish. Fernand Léger died at his home in 1955 and is buried in Gif-sur-Yvette, Essonne.

Legacy

Léger wrote in 1945 that "the object in modern painting must become the main character and overthrow the subject. If, in turn, the human form becomes an object, it can considerably liberate possibilities for the modern artist." He elaborated on this idea in his 1949 essay, "How I Conceive the Human Figure", where he wrote that "abstract art came as a complete revelation, and then we were able to consider the human figure as a plastic value, not as a sentimental value. That is why the human figure has remained willfully inexpressive throughout the evolution of my work".[22] As the first painter to take as his idiom the imagery of the machine age, and to make the objects of consumer society the subjects of his paintings, Léger has been called a progenitor of Pop Art.[23]

He was active as a teacher for many years, first at the Académie Vassilieff in Paris, then in 1931 at the Sorbonne, and then developing his own Académie Fernand Léger, which was in Paris, then at the Yale School of Art and Architecture (1938–1939), Mills College Art Gallery in Oakland, California during 1940–1945, before he returned to France.[24] Among his many pupils were Nadir Afonso, Paul Georges, Charlotte Gilbertson, Hananiah Harari, Asger Jorn, Michael Loew, Beverly Pepper, Victor Reinganum, Marcel Mouly, René Margotton, Saloua Raouda Choucair and Charlotte Wankel, Peter Agostini, Lou Albert-Lasard, Tarsila do Amaral, Arie Aroch, Alma del Banco, Christian Berg, Louise Bourgeois, Marcelle Cahn, Otto Gustaf Carlsund, Saloua Raouda Choucair, Robert Colescott, Lars Englund, Tsuguharu Foujita, Sam Francis, Serge Gainsbourg, Hans Hartung, Florence Henri, Asger Jorn, William Klein, Maryan, George Lovett Kingsland Morris, Marlow Moss, Aurélie Nemours, Gerhard Neumann, Jules Olitski, Erik Olson, Richard Stankiewicz and Stasys Usinskas.[24]

In 1952, a pair of Léger murals was installed in the General Assembly Hall of the United Nations headquarters in New York City.[25]

In 1960, the Musée Fernand Léger was opened in Biot, Alpes-Maritimes, France.

In May 2008, his painting Étude pour la femme en bleu (1912–13) sold for $39,241,000 (hammer price with buyer's premium) United States dollars.[26]

In August 2008, one of Léger's paintings owned by Wellesley College's Davis Museum and Cultural Center, Mother and Child, was reported missing. It is believed to have disappeared some time between April 9, 2007 and November 19, 2007. A $100,000 reward is being offered for information that leads to the safe return of the painting.[27]

Léger's work was featured in the exhibition "Léger: Modern Art and the Metropolis" from October 14, 2013, through January 5, 2014, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[28]

Gallery

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_82.2_x_97.8_cm%252C_Minneapolis_Institute_of_Arts.jpg.webp) Le compotier (Table and Fruit), 1910–11, oil on canvas, 82.2 × 97.8 cm, Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Reproduced in Du "Cubisme", 1912

Le compotier (Table and Fruit), 1910–11, oil on canvas, 82.2 × 97.8 cm, Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Reproduced in Du "Cubisme", 1912%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_194.9_%C3%97_116.5_cm%252C_Milwaukee_Art_Museum.jpg.webp) Étude pour trois portraits (Study for Three Portraits), 1911, oil on canvas, 194.9 × 116.5 cm, Milwaukee Art Museum

Étude pour trois portraits (Study for Three Portraits), 1911, oil on canvas, 194.9 × 116.5 cm, Milwaukee Art Museum Les Toits de Paris (Roofs in Paris, 1911, oil on canvas, private collection. Reproduced in Du "Cubisme", 1912

Les Toits de Paris (Roofs in Paris, 1911, oil on canvas, private collection. Reproduced in Du "Cubisme", 1912%252C_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art.jpg.webp) Composition (Study for Nude Model in the Studio), 1912, oil, gouache, and ink on paper, 63.8 × 48.3 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Composition (Study for Nude Model in the Studio), 1912, oil, gouache, and ink on paper, 63.8 × 48.3 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_92_x_81_cm.jpg.webp) Paysage (Landscape), 1912–13, oil on canvas, 92 × 81 cm

Paysage (Landscape), 1912–13, oil on canvas, 92 × 81 cm%252C_published_in_Der_Sturm%252C_5_September_1920.jpg.webp) Contrast of Forms (Contraste de formes), 1913. Published in Der Sturm, 5 September 1920

Contrast of Forms (Contraste de formes), 1913. Published in Der Sturm, 5 September 1920.jpg.webp) Nature morte (Still life), 1914

Nature morte (Still life), 1914%252C_oil_on_burlap%252C_74_x_93_cm%252C_Albright-Knox_Art_Gallery.jpg.webp) Paysage No. 1 (Le Village dans la forêt), 1914, oil on burlap, 74 x 93 cm, Albright-Knox Art Gallery

Paysage No. 1 (Le Village dans la forêt), 1914, oil on burlap, 74 x 93 cm, Albright-Knox Art Gallery Le Fumeur (The Smoker), 1914, oil on canvas, 100.3 x 81.3 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Le Fumeur (The Smoker), 1914, oil on canvas, 100.3 x 81.3 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art.jpg.webp) Dans L'Usine, 1918, oil on canvas, 56 × 38 cm

Dans L'Usine, 1918, oil on canvas, 56 × 38 cm%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_231.1_x_298.4_cm%252C_Philadelphia_Museum_of_Art.jpg.webp)

The Railway Crossing, 1919, oil on canvas, 54.1 × 65.7 cm, Art Institute of Chicago

The Railway Crossing, 1919, oil on canvas, 54.1 × 65.7 cm, Art Institute of Chicago_1958_made.jpg.webp) Grand parade with red background, 1958 (designed in 1953), mosaic, National Gallery of Victoria

Grand parade with red background, 1958 (designed in 1953), mosaic, National Gallery of Victoria

References and sources

- References

- Néret 1993, p. 35.

- Robert L. Herbert, From Millet to Léger: Essays in Social Art History, p. 115, Yale University Press, 2002, ISBN 0300097069

- Néret 1993, pp. 35–38.

- Néret 1993, p. 242.

- Néret 1993, p. 102.

- Néret 1993, p. 66.

- Buck 1982, p. 141.

- Cowling and Mundy 1990, pp. 136–138.

- Eliel 2001, p. 37.

- Néret 1993, p. 119.

- Eliel 2001, p. 44.

- Eliel 2001, p. 58.

- Cowling and Mundy 1990, p 144.

- Buck 1982, p. 23.

- Néret 1993, p. 246.

- Buck 1982, p. 48.

- Néret 1993, pp. 210–217.

- Buck 1982, pp. 53–54.

- Buck 1982, p. 52.

- Buck 1982, p. 143.

- Buck 1982, p. 58.

- Néret 1993, p. 98.

- Buck 1982, p. 42.

- Pupils Fernand Léger in the RKD

- An 'element of inspiration and calm' at UN Headquarters – art in the life of the United Nations Retrieved October 13, 2010

- Étude Pour la Femme En Bleu, record price at public auction, Sotheby's New York, 7 May 2008

- Geoff Edgers, A masterwork goes missing, The Boston Globe, August 27, 2008

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Sources

- Bartorelli, Guido (2011). Fernand Léger cubista 1909-1914. Padova, Italy: Cleup. ISBN 978-88-6129-656-5.

- Buck, Robert T. et al. (1982). Fernand Léger. New York: Abbeville Publishers. ISBN 0-89659-254-5.

- Cowling, Elizabeth; Mundy, Jennifer (1990). On Classic Ground: Picasso, Léger, de Chirico and the New Classicism 1910-1930. London: Tate Gallery. ISBN 1-85437-043-X.

- Eliel, Carol S. et al. (2001). L'Esprit Nouveau: Purism in Paris, 1918-1925. New York: Harry Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-6727-8.

- Léger, Fernand (1973). Functions of Painting. New York: Viking Press. Translation by Alexandra Anderson.

- Léger, Fernand (2009). F. Léger. exhibition catalogue. Paris: Galerie Malingue. ISBN 2-9518323-4-6.

- Néret, Gilles (1993). F. Léger. New York: BDD Illustrated Books. ISBN 0-7924-5848-6.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Fernand Léger |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fernand Léger. |

- Works by or about Fernand Léger at Internet Archive

- Artcyclopedia - Links to Léger's works

- Fernand Léger at the Museum of Modern Art

- Artchive - Biography and images of Léger's works

- Ballet Mecanique - Watch Fernand Léger's Short Film

- Paintings by Fernand Léger (public domain in Canada)

- Fernand Léger, L'Esprit nouveau: revue internationale d'esthétique, 1920. Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Fernand Léger in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website