Fifth Avenue Hotel

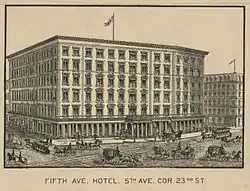

The Fifth Avenue Hotel was a luxury hotel located at 200 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, New York City from 1859 to 1908. It had an entire block of frontage between 23rd Street and 24th Street, at the southwest corner of Madison Square.

| Fifth Avenue Hotel | |

|---|---|

(1860) | |

| |

| General information | |

| Address | 200 Fifth Avenue |

| Coordinates | 40.74205°N 73.98945°W |

| Construction started | 1856 |

| Completed | 1859 |

| Inaugurated | 23 August 1859 |

| Demolished | 1908 |

| Owner | Amos R. Eno |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Griffith Thomas with William Washburn |

Site and construction

_-_jpg_version.jpg.webp)

The site was previously used by Madison Cottage,[2] which was a stagecoach stop for passengers headed north from the city. From 1853 to 1856 it was then used by Franconi's Hippodrome, a tent-like structure of canvas and wood which could accommodate up to 10,000 spectators who watched chariot races and other "Amusements of the Ancient Greeks and Romans".[3][4][5]

The Fifth Avenue Hotel was built in 1856–59 by Amos Richards Eno at the cost of $2 million. The building was designed by Griffith Thomas with William Washburn.[6] Due to the site's location away from the city centre, The hotel was labelled as the "Eno's Folly"[7] during construction, due to its location away from the city centre.

Following the hotel's opening, it became "the social, cultural political hub of elite New York,"[8] and brought in a quarter of a million dollars a year in profits.[8] The Fifth Avenue Hotel spurred development of additional hotels to the north and west,[9] in the North of the Madison Square Park, otherwise known as NoMad in the 21st century.

Design and accommodations

The Fifth Avenue Hotel was constructed of brick and white marble, and stood at five storeys over a commercial ground floor. The first example of Otis Tufts' "vertical screw railway," the first passenger elevator installed in a hotel in the United States,[10] a notable but cumbersome feature powered by a stationary steam engine carried passengers to the upper floors by a revolving screw that passed through the center of the passenger cab.[11]

The building was of a plain Italianate palazzo-front design, with a projecting tin cornice, but its sober exterior contained richly appointed public rooms: Harper's Weekly reviewed its "heavy masses of gilt wood, rich crimson or green curtains, extremely handsome rose-wood and brocatelle suits,[12] rich carpets... the whole presenting about as handsome and as comfortless an appearance as any one need wish for."[13] A correspondent for The Times of London, in New York to cover the visit of the Prince of Wales in 1860, called the hotel "a larger and more handsome building than Buckingham Palace."[6]

The hotel employed 400 servants to serve its guests,[6] offered private bathrooms (an unprecedented amenity at the time)[6] and ran advertisements featuring a fireplace in every room.[14] Some critics has argued that the success of the hotel is a sign that elite New Yorkers were rejecting the republican values of their forefathers, and had begun to value grandeur, luxury and comfort instead.[6]

Notable events and uses

The hotel was host to numerous notable guests, both foreign and domestic, and was, for a time, the most exclusive hotel in the city, and the center of social life for elite New Yorkers.[15]

President Ulysses S. Grant's campaign began at a dinner party in the hotel, and he and his cabinet once held an official session there.[16] The celebrity lawyer Chester A. Arthur – who later became President of the United States – kept a suite for his office;[17] Edward, Prince of Wales, stayed here on his North American tour, as did his brother-in-law the Duke of Argyll, Dom Pedro of Brazil and Prince Agustín de Iturbide y Green of Mexico, Maximilian's adopted son.[18] "It was a gathering place for fat cats like Boss Tweed, Jay Gould, Jim Fisk and Commodore Vanderbilt, who would trade stocks here after hours."[19] The celebrated New York City physician, Dr. John Franklin Gray, lived at the hotel. When the superbly confident young Jim Fisk first arrived in New York, he stayed at the Fifth Avenue hotel until he was temporarily ruined.[20] Gore Vidal made the Fifth Avenue Hotel a setting in his novel 1876, for it was in a suite here that John C. Reid, editor of The New York Times woke the Republican National Committee chairman Zachariah Chandler, and worked out the campaign for the controversial Presidential election of 1876.

On May 21, 1881, the United States Tennis Association was founded in the Fifth Avenue Hotel.[21]

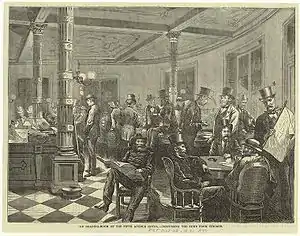

"Amen Corner"

The Fifth Avenue Hotel was known as a stronghold of the Republican Party.[15] From a corner nook in one of the public rooms, which he dubbed his "Amen Corner", Republican political boss Thomas Collier Platt controlled patronage in New York City and State for a few years in the 1890s; here he held his "Sunday School", where projects did not go forward until they had his "amen".[22][23][24]

Closing and demolition

The Fifth Avenue Hotel closed at midnight, 4 April 1908[25] and was demolished. It was reported that patrons of the hotel's bar spent $7,000 in drinks during its last day of operation.[22]

Its site was occupied in 1909 by an office building known as the Fifth Avenue Building (later changed to Toy Center), designed by Robert Maynicke and Julius Franke,[26] for Eno's grandson, Henry Lane Eno. Until 2007 it housed the International Toy Center,[27] which was filled with wholesale buyers come the February Toy Fair[28] and then again in October. The old hotel's name was taken up by a Fifth Avenue Hotel at 24 Fifth Avenue, a grid of windows in a brick facade, by Emery Roth, later converted to apartments.[29]

A plaque on the Toy Center, the building currently on the site, commemorates the hotel.[30]

See also

References

Notes

- Federal Writers' Project (1939). "New York City Guide". New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.), p.307

- The farmhouse of John Horn, from which the Bloomingdale Road took its start, was shifted from its position in the middle of the surveyed but unbuilt Fifth Avenue in November 1839. (Kelley, Frank Bergen and Hagaman, Edward. Historical Guide to the City of New York [City History Club of New York] 1909:112).

- Wilson, 1902:242. "This huge arena seated about six thousand people with room for three thousand standees. The structure was rather an immense tent than a building. Pageants with elephants and camels, chariot races, and gladiatorial contests in keeping with the Roman name were staged there for two seasons, but the enterprise was not a financial success." Patterson, Jerry E. Fifth Avenue: The Best Address 1998.

- Event Horizon: Mad. Sq. Art.: Antony Gromley installation guide, published by the Madison Square Park Conservancy (2010)

- Alexiou, Alice Sparberg (2010), The Flatiron: The New York Landmark and the Incomparable City that Arose With It, New York: Thomas Dunne/St. Martin's, ISBN 978-0-312-38468-5, p.24

- Burrows, Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-11634-8. p. 672

- For comparison, Fifth Avenue's first hotel, the stylish Brevoort Hotel, opened just eight years earlier (1851), stood on the northeast corner at Eighth Street.

- Miller 2001:47

- Landmarks Preservation Commission designation summary for The Wilbraham, 8 June 2004 Archived 11 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine,

- Patented 9 August 1859. As late as 1908 a tablet in one of the hotel's elevators recorded its former site. The unwieldy elevator was replaced by Tufts' rope elevator in 1879, according to Walsh, William Shepard, A Handy Book of Curious Information, 1913:334.

- Klaw, Spencer. "'All safe, Gentlemen, all safe!' The ups and downs of the invention that forever altered the American skyline" American Heritage, 29.5 (August/September 1978: on-line text Archived 2008-12-01 at the Wayback Machine).

- Suites of rosewood furniture with brocatelle marble tops are intended.

- Quoted in Miller, 2001:47

- Korom, Joseph J. The American Skyscraper, 1850-1940: a celebration of height 2001:41f.

- Mendelsohn, Joyce (1998), Touring the Flatiron: Walks in Four Historic Neighborhoods, New York: New York Landmarks Conservancy, ISBN 0-964-7061-2-1, OCLC 40227695, pp.16-17

- Sprague, Stuart Seely (1977). "Lure of the city: New York's great hotels in the golden age, 1873-1907". Conspectus of History. 1 (4): 74.

- Karabell, Zachary. Chester Alan Arthur 2004:35.

- Wilson 1902:243

- "New York Songlines: Fifth Avenue";

- Renehan, Edward J., Jr., Dark Genius of Wall Street 2006:110.

- Tennis, a Cultural History by Heiner Gillmeister, Leicester University Press, 1997

- Blecher, George (August 3, 2018) "Murder, Politics and Architecture: The Making of Madison Square Park" The New York Times

- Miscione, Michael (December 18, 2004)"The Fifth Avenue Hotel" The New York Times

- Adams, James Truslow ed. (1940) "Amen Corner" in Dictionary of American History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons

- "Fifth Avenue Hotel Closes at Midnight", New York Times, 4 April 1908: "Odell and Platt Will Greet Their Friends in the "Amen Corner" To-day for the Last Time. Employees Say Good-bye; Bids from All Over the Country Received for Fittings with Historic Associations". Accessed 28 August 2008.

- Landmark permit, December 19, 2007 Archived February 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- International Toy Center Archived February 17, 2001, at the Wayback Machine.

- Michael Specter, "Not all fun and games at the 5th. Ave. toy center," The New York Times, April 26, 1981

- NYCJPG: Fifth Avenue Hotel Archived September 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Mendelsohn, Joyce. "Madison Square" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300055366., p. 711-712

Bibliography

- Miller, Char. Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism 2001

- Wilson, Rufus Rockwell. New York: Old & New: Its Story, Streets, and Landmarks, 1902

External links

Media related to Fifth Avenue Hotel at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fifth Avenue Hotel at Wikimedia Commons