Fort Carillon

Fort Carillon, the precursor of Fort Ticonderoga, was constructed by Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, Governor of Canada, to protect Lake Champlain from a British invasion. Situated on the lake some 15 miles (24 km) south of Fort Saint Frédéric, it was built to prevent an attack on Canada and slow the advance of the enemy long enough for reinforcements to arrive.[1]

| Fort Carillon | |

|---|---|

Fort Carillon (modern day Fort Ticonderoga) | |

| Coordinates | 43°50′29″N 73°23′17″W |

| Type | Fort |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | New France |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1755 |

| In use | 1755–1759 |

| Battles/wars | Seven Years War |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | |

| Garrison | |

Assigned to remedy Fort Saint Frédéric's inability to resist a constant British threat to the south, French King's Engineer Michel Chartier de Lotbinière began construction of Fort Carillon where Lake George, at that time called Lac Saint Sacrement, joins Lake Champlain by the La Chute river. Construction began in October 1755.[2]

Location

Fort Carillon was situated south of Lake Champlain and north of Lake George, a natural point of conflict between the French forces, which were advancing south from Quebec City through the Richelieu River towards Lake Champlain and the Hudson Valley, and the British forces, which were hoping to move north. The area was chosen so as to control the southern point of Lake Champlain as well as access to the Hudson Valley. The fort is surrounded by water on three sides, and on half of the fourth side by a moat. The portion remaining was strongly fortified by deep trenches, sustained by three batteries of cannon and, in front of the fort, blocked by trees which had been cut down and the pointed ends strengthened by fire, creating a formidable defensive system.

Handicapped by corruption, the construction continued at a slow pace. By mid-July 1756, four bastions with cannon were placed at a height of 18 ft (5.5 m). Two of the bastions were directed to the northeast and northwest, away from the lake. They were the Reine and Germaine bastions, with two demilunes (an outwork in front of a fort, shaped like a crescent moon) further extending the works on the land side. The two other bastions provided cover for the landing area outside the fort. They were the Joannes and Languedoc bastions, which overlooked the lake to the south. The walls were seven feet (2.1 meters) high and fourteen feet (4.3 meters) thick, and the whole works was surrounded by a glacis and a dry moat five feet (1.5 metres) deep and 15 feet (4.6 m) wide. The fort was armed with cannon brought in from Fort St. Frédéric and Montréal.[3][4]

By fall, the fort was still not finished when an important discovery was made: as soon as the trees of the peninsula were cut, the French realized that the location they chose did not join well with the junction between the two lakes. To correct this, a second but smaller fort was built closer to the lake, known as Redoute des Grenadiers. By January 1757, the fort was still incomplete and composed of earth and moats, mounted by 36 cannon waiting for an attack that the French were anticipating. The French and Canadians did not want to wait passively for the British assault however, and decided to attack first. In April, 8,000 men, under the command of Marquis de Montcalm, mustered at Fort Carillon. In August 1757, they crossed Lake George to take Fort William Henry. The operation was a success and Montcalm brought back his men to Fort Carillon for the summer.[2]

Lower and upper town of Carillon

In 1756, the Canadian and French troops developed "le Jardin du Roi" on the sandy plain below the heights. It was intended to feed the summer garrison charged with constructing the new fort.[5]

By 1758, Fort Carillon and its surroundings were composed of a lower town, an upper town, two hospitals, hangars, and barracks for the soldiers. The lower town itself took the form of a triangle with the fort as its northern tip, and the lower town the southern part of the triangle. There, taverns with wine cellars for the soldiers, bakeries, and nine ovens were located.[5] It was important to construct batteries for the lower town, and the earth removed for construction of the lower town was taken closer to the fort.[6]

On July 22, 1759, when orders were given to set fire to the town, the Indians could not believe that the French and Canadians would abandon what they had worked so hard to build. Heavy smoke rose from the two hospitals, the hangars of the lower and upper town, and the soldiers' barracks. All was to be abandoned to the advancing British army.[7] None of the buildings were ever reconstructed as was the case in Louisbourg, Cape Breton.

Garrison at Fort Carillon

Les troupes de terre

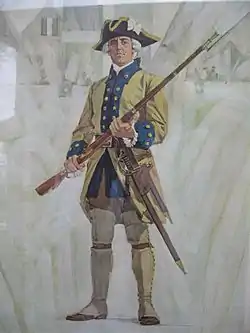

The troupes de la terre were composed of professional soldiers of the French Army, sent from France to America, who were disciplined and well trained. At Fort Carillon in 1758, these troops were made up of the second battalions of seven regiments sent from different regions of France.[8] The regiments represented in the garrison were those of La Reine (345 soldiers), Guyenne (470 soldiers), Berry (450 soldiers), Béarn (410 soldiers), La Sarre (460 soldiers), Royal Roussillon (480 soldiers), and Languedoc (426 soldiers). The Berry regiment also had a second battalion, but their numbers were not known.[9] The requisite white uniform of the French regular infantry is likely to have been similarly modified for all the battalions. The uniform of the Régiment de Guyenne and Régiment Berry was a bit like the Régiment de la Reine: a white-grey coat with red reversed sleeves with three ornate buttons, red vest, white-grey pants, and black shoes with metallic buckles. However, contrary to La Reine, the tricorn hat was black felt with a gold medallion.[10] The uniforms of the other regiments had blue vests and blue cuffs, except for Régiment de La Sarre which had red vests and blue cuffs. The French musket was of a smaller caliber than the British musket.

Les troupes de la Marine

The Troupes de la Marine were led by Chevalier de Lévis with 150 Canadians. There were also about 250 Canadian Indians at Fort Carillon, for a total of 3,500 soldiers.[9] The French and Canadians often made use of guns placed on the walls of the fort, although for the Battle of Carillon, because the fighting took place 3/4 of a mile from the fort, it was essentially a battle of musket and bayonet.

Fort Carillon 1757

Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, in command of the French troops at Fort Carillon decided to attack Fort William Henry from Fort Carillon. On August 9, 1757, Montcalm, with an army of 7,000 men consisting of French soldiers, Canadian militia, and Indians from various tribes, took Fort William Henry, situated at the southern point of Lake George. The Indians, who thought that an agreement had been made without their consent, revolted. What ensued were violent attacks by the Indians intoxicated by alcohol. There were, according to sources, between 70 and 150 people killed, scalped, and decapitated. After this massacre, the French soldiers accompanied the survivors to Fort Edward to avoid further bloodshed.[11]

After his victory, Montcalm could have taken Fort Edward, but he took instead the destroyed Fort William Henry, and returned to Fort Carillon. The British had been humiliated and Montcalm had shown the compassion of a great general by stopping any further bloodshed by the Indians and accompanying the survivors. However, Montcalm knew that he had to withdraw because of the anger and loss of the Indians as allies, as well as a shortage of provisions.

In 1756, New France had suffered a disastrous crop failure. Montcalm was forced to release the Canadian militiamen who made up more than half of his force. The Canadians were urgently needed to return home for the harvest. However, in 1757, disaster struck again and the harvest was the worst in Canadian history. Conditions were particularly bad around Montreal, which was "the granary of Canada." By late September, the inhabitants were subsisting on a half-pound of bread a day, and those at Quebec on a quarter-pound of bread. A month later, there was no bread at all. "The distress is so great that some of the inhabitants are living on grass," Bougainville wrote. There was a feeling of dispirited despair in the colony and the conclusion was that its military prospects would soon become indefensible.[12]

After a string of French victories in 1757, the British were prompted to organize a large-scale attack on the fort as part of a multifaceted campaign strategy against Canada.[13] In June 1758, British General James Abercrombie began amassing a large force at Fort William Henry in preparation for the military campaign directed up the Champlain Valley. These forces landed at the north end of Lake George, only four miles from the fort, on July 6.[14] The French general Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, who had only arrived at Carillon in late June, engaged his troops in a flurry of work to improve the fort's outer defenses. They built, over two days, entrenchments around a rise between the fort and Mount Hope, about three-quarters of a mile (one kilometer) northwest of the fort, and then constructed an abatis (felled trees with sharpened branches pointing out) below these entrenchments.[15] Abercrombie's failure to advance directly to the fort on July 7 made much of this defensive work possible. Brigadier General George Howe, Abercromby's second-in-command, had been killed when his column encountered a French reconnaissance troop. Abercrombie "felt [Howe's death] most heavily" and may have been unwilling to act immediately.[16]

1757 was therefore a bad year for the British in North America, not only because of their defeat in northern New York, but in the Ohio Valley and Nova Scotia as well. That year, British Prime-Minister William Pitt named General James Wolfe commander of the British troops in North America.[11]

British force sent against Fort Carillon

The British force sent against Fort Carillon was made up of regular British regiments and provincial regiments. The British units were the 27th (Enniskillen) Regiment of Foot, the 42nd (Highland) Regiment of Foot, the 44th Regiment of Foot, 46th Regiment of Foot, the 55th Regiment of Foot, the 1st and 4th battalions of 60th (Royal American) Regiment, and Gage's Light Infantry.[17]

The British regiments were in their customary red coats with the exception of Gage's light infantry, which wore grey. The soldiers were armed with muskets, bayonets, hatchets or tomahawks, and knives. The standard battle issue for British soldiers was 24 rounds of ammunition; Howe may have ordered his soldiers to carry as many rounds as they could. The provincial regiments wore blue, but extensive modification of uniform was made to suit forest warfare with coats being cut back and any form of headgear and equipment permitted. Rogers' Rangers most likely wore their distinctive green. Along with Rogers' Rangers, there were regiments from New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Jersey.[17]

Early preparations to the Battle of Carillon (1758)

Although the French government knew that the British had dispatched 8,000 men to North America, Canada had only received 1,800 men, most of whom were assigned to Louisbourg. The army's small size forced Major-General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, commander of French forces in Canada, to rely on Indians, and although traditional French allies like the Nipissing, Algonkin, and Abenaki contributed a thousand warriors, it was not enough. Determined to capture both Fort William Henry and Fort Edward, Governor Vaudreuil also recruited a thousand warriors from tribes around the upper Great Lakes. The large number of different tribes meant that there were not enough interpreters, and potentially dangerous tribal rivalries needed attention. Dealing with Indians was never an easy matter, but these Indians did not see themselves as subjects of New France, just temporary allies in search of loot. However, even traditional French allies had scalped wounded British when the garrison at Oswego surrendered, and then forced the French to buy back a number of English prisoners.[11]

While Montcalm and Vaudreuil were raising an army, American rangers proved to be too few to stop Indians from raiding the area around Fort William Henry at will. In late June, a powerful Indian raiding party discovered that the road between the two forts was basically unguarded. The French had a clear picture of the strategic situation in June, but six separate scouting parties were unable to penetrate the Indian screen to learn anything more detailed than that there was a large force at Fort Carillon.[18]

The destruction of Fort William Henry should have guaranteed the safety of Fort Carillon, but the British government had made North America the priority, while France had not, so another attempt was made at Fort Carillon.

Battle of Fort Carillon

The British were alarmed by the outcome of losing Fort William Henry, which was their northernmost fort. They decided to prepare for a massive attack against Fort Carillon. Close to 16,000 men (the largest troop deployment ever assembled on the North American continent) was united under the orders of General James Abercrombie, commander in chief of the British forces in North America. The actual officer in charge of the land operation was Brigadier-General Lord Howe. On July 8, 1758, the British army of General James Abercrombie with 16,000 men, (6,000 British soldiers and 10,000 colonials) and their allies the Mohawks (who did not participate in the battle), attacked Fort Carillon commanded by Louis-Joseph de Montcalm with 3,600 soldiers, including 400 Canadians from Lévis and 300 Abenakis. Abercrombie was determined to go ahead with his advancement before he lost the advantage. The British however faced a well-fortified position. While the fort was still under construction,, the French forces dug deep trenches flanked by three batteries of cannon. The fort was also defended by a line of sharpened trees pointed towards the exterior and intertwined with branches and spikes installed during the night on orders from Montcalm. Part of the French forces were dispersed in the adjoining forest. The land around the fort gave way to only one opening, since the fort was surrounded on three sides by water and at half of the rear by a moat. Abercrombie could have gone around the French, but wanting a quick victory, he decided against this maneuver. Informed by his lieutenant that it would be possible to take the French by assault, he opted for a massive frontal attack. However, the French defenses proved to be well prepared and they were not in danger of enemy fire. The French easily decimated the British ranks with cannon fire. (The French were lined up in 3 rows: the first row fired while the third was reloading their rifles, permitting a strong even fire).[19]

The British soldiers had to climb on each other's shoulders in order to reach the top of the trenches, so it was easy for the French to repulse them as they arrived near the summit of the defenses. Only one time were the British capable of breaking through the French defenses, only to be repulsed by a charge of bayonets. The British tried to take the fort, but were driven back time and time again by the French artillery. Abercrombie sent his men to assail the fort several times; he lost 551 soldiers, 1,356 were wounded and 77 disappeared. They retreated to Fort William Henry. As for the French and Canadians, they had 104 killed and 273 wounded.[20]

British capture

Jeffery Amherst, now commander in chief of the British forces in America with 12,000 soldiers, prepared to move against Fort Carillon on July 21, 1759. On July 22 and 23, Bourlamaque left the fort with 3,600 men and deployed 400 soldiers to set fire to the two hospitals, hangars, barracks, and to the lower part of the town. During four days, from July 23 to 26, the British bombed the fort, using artillery positioned where Captain Hébécourt and his men were retrenched. On July 26, they left at 10 PM, and at midnight, the explosives demolished most of the fort.[21] They then moved out to Fort Saint Frédéric with the regiment of Hébécourt, captain of the La Reine regiment. Bourlamaque did the same to Fort Saint Frédéric on July 31. After that, they moved up to Isle-aux-Noix where Amherst declined to advance against them, preferring to consolidate his forces in the lower Lake Champlain area.[22] In withdrawing, the French used explosives to destroy what they could of the fort and spiked or dumped cannon they did not take with them.[23] The British moved in on July 27 and, though they worked in 1759 and 1760 to repair and improve the fort (which they renamed Fort Ticonderoga),[24] the fort saw no more significant action in the war. After the war, the British garrisoned it with a small number of troops but allowed it to fall into disrepair. Colonel Frederick Haldimand, in command of the fort in 1773, wrote that it was in "ruinous condition".[25]

Photos of Fort Carillon

Legacy of Fort Carillon

The importance of Fort Carillon, the Battle of Carillon, and the Flag of Carillon; have long been a source of pride for French Canadians and to the people of Quebec.[26] The Flag of Quebec was modeled after the Carillon flag and the Fort and its history bring honor to Canada as well as the province of Quebec.

See also

References

- W. J. Eccles. France in America, Harper and Row, 1973 p186

- Boréal Express, Canada-Québec, Éditions du Renouveau Pédagogique Inc. 1977

- Kaufmann, pp. 75–76

- Lonergan (1959), p. 19

- The bulletin of Fort Carillon, p.141-142

- François Gaston Lévis (duc de), Henri Raymond Casgrain 1 Commentaire, C.O. Beauchemin & fils, 1895 – p. 320

- Lettres de Montcalm, C.O. Beauchemin & fils, 1895 – p. 286

- Germain, Jean-Claude Nous étions le Nouveau Monde, Hurtibise, p142 2009

- http://grandquebec.com/histoire/bataille-de-carillon/

- Nous étions le Nouveau Monde, Jean-Claude Germain, Hurtibise, p143 2009

- Jacques Lacoursière, Tome I de son Histoire populaire du Québec page 345.

- Jacques Lacoursière, Tome I de son Histoire populaire du Québec page 346.

- Anderson (2005), p. 126

- Anderson (2005), p. 132

- Anderson (2000), p. 242

- Anderson (2005), p. 135

- "Bataille de Carillon", Grandquebec.com (in French)

- Jacques Lacoursière, Tome I de son Histoire populaire du Québec page 347.

- Nos racines, l'histoire vivante des Québécois, Éditions Commémorative, Livre-Loisir Ltée.

- W. J. Eccles. France in America, Harper and Row, 1973 p195

- Histoire populaire du Québec, Volume 1 By Jacques Lacoursière p.295

- Jacques Lacoursière, Jean Provencher, Denis Vaugeois Canada-Québec: synthèse historique, 1534–2000 p139

- Lonergan (1959), p. 56

- Kaufmann, pp. 90–91

- Lonergan (1959), p. 59

- H.-J.-J.-B. Chouinard, Annales de la Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Québec, volume IV, Québec, la Cie d'imprimerie du «Soleil», 1903, p. 562

External links

- Visit to Fort Carillon 2008 http://www.lestafette.net/t1760-vv-86-visite-au-fort-carillon

- Béarn regiment at Fort Carillon http://reconstitution.fr/histoire_fort_carillon.html

- Artwork depicting Fort Carillon in 1759 http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/quebechistory/encyclopedia/FortCarillon.html