Fort Vieux Logis

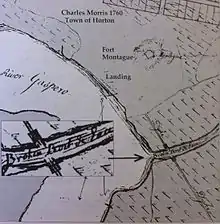

Fort Vieux Logis (later named Fort Montague) was a small British frontier fort built at present-day Hortonville, Nova Scotia, Canada (formerly part of Grand Pre) in 1749, during Father Le Loutre's War (1749).[1][2][3] Ranger John Gorham moved a blockhouse he erected in Annapolis Royal in 1744 to the site of Vieux Logis.[4][5][6][7][8] The fort was in use until 1754.[9][10] The British rebuilt the fort again during the French and Indian War and named it Fort Montague (1760).

| |

| |

| Established | 1749 - 1754 |

|---|---|

| Location | Hortonville, Nova Scotia, Canada |

| Type | National Historic Site |

| Website | Grand Pre National Historic Park |

The site of the fort is near the field where the Acadian Cross and the New England Planter's monument are located. Despite archeological efforts, the exact location of the fort is unknown.[11]

Despite the British Conquest of Acadia in 1710, Nova Scotia remained primarily populated by Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. During King George's War, the British tried to occupy further up the Bay of Fundy, starting with Grand Pre. They built a palisade which was involved with in the Siege of Grand Pre.

Father Le Loutre’s War

Father Le Loutre's War began when Edward Cornwallis arrived to establish Halifax with 13 transports on June 21, 1749.[12] The British quickly began to build other settlements. To guard against Mi'kmaq, Acadian and French attacks on the new Protestant settlements, British fortifications were erected in Halifax (1749), Bedford (Fort Sackville) (1749), Dartmouth (1750), Lunenburg (1753) and Lawrencetown (1754).[13]

Within 18 months of establishing Halifax, the British also took firm control of peninsula Nova Scotia by building fortifications in all the major Acadian communities: present-day Windsor (Fort Edward); Grand Pre (Fort Vieux Logis) and Chignecto (Fort Lawrence). (A British fort already existed at the other major Acadian centre of Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. Cobequid remained without a fort.)[13] The fort was created to help prevent the Acadian Exodus from the region.[14]

The journal of Henry Grace includes a description of Fort Vieux Logis:

- Menas [sic] Fort is built with square Timber and placed Piece upon Piece with Blockhouses in it, the same as Pisgate (Fort Edward). There is not much open Land about it, only where the French Neutrals lived.[15]

Siege of Grand Pre

On November 27, 1749, 300 of the Wabanaki Confederacy (Mi'kmaq, Maliseet) and Acadians attacked the British Fort Vieux Logis. The fort was under the command of Captain John Handfield.[16] While surveying the fort's environs, Lieutenant John Hamilton and eighteen soldiers (including Captain Handfield's son John) under his command were captured.[17] After the British soldiers were captured, the native and Acadian militias made several attempts over the next week to lay siege to the fort before breaking off the engagement. Gorham’s Rangers was sent to relieve the fort. When he arrived the militia had already departed with the prisoners. The prisoners spent several years in captivity before being ransomed.[18]

In 1750, six British soldiers from the 40th Regiment of Foot tried to desert the fort. Cornwallis sentenced them to death. Two of them were shot. Three of them were hanged and their bodies left to hang in chains.[19][20]

The first raid on Halifax happened in October 1750, while in the woods on peninsular Halifax; Mi'kmaq scalped two British people and took six prisoner: Cornwallis' gardener, his son were tortured and scalped. The Mi'kmaq buried the son while the gardener's body was left behind. Cornwallis presumed the other six prisoners were also killed and it was not until five months later he discovered they were being held prisoner at Grand Pre. In response, Cornwallis had soldiers from Fort Vieux Logis take ransom the local priest until the six British prisoners were released.[21][22]

November 1, 1753, Captain Cox was the commander of Fort Vieux Logis.[23]

The improvised nature of the fort, whose palisade was so low that snow drifts often buried them, and its exposed location, overlooked by nearby hills, led the British to abandon it in 1754. When new British troops were sent to Grand Pre for the Expulsion of the Acadians in 1755, they chose the church at Grand Pre as their base instead.[24]

The blockhouse was rebuilt in 1760 and named Fort Montague, named after Montague Wilmot.[4]

Commanders

- Captain John Handfield

- Capt Matthew Floyer[25]

- Nicholas Cox, commander (1753–54) (who later became a commander at Fort Edward)

See also

References

Texts

- Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Griffiths, N.E.S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Murdoch, Beamish (1866). A History of Nova-Scotia, Or Acadie. Vol. II. Halifax: J. Barnes.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wicken, William (2002). Mi'kmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land, and Donald Marshall Junior. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-7665-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Young, Richard. "Blockhouses in Canada, 1749-1841: a Comparative Report and Catalogue." Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History, Canadian Historic Site, 1980.

Endnotes

- p.3 primary source

- Northeast Archaeological Research "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-05-14. Retrieved 2014-02-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Murdoch (1866), p. 226

- http://www.northamericanforts.com/Canada/ns.html#mohawk

- http://www.accessgenealogy.com/native/mohawk-monument-annapolis-royal-nova-scotia.htm

- The fort at Annapolis Royal was named Fort Mohawk (first built by Mohawks under Major John Livingston in 1712).

- https://archive.org/stream/historyofkingsco00eato#page/426/mode/2up

- Murdoch (1866), p. 623

- https://archive.org/stream/selectionsfrompu00nova#page/n115/mode/1up

- https://archive.org/stream/selectionsfrompu00nova#page/n118/mode/1up

- Fort Vieux Logis Archived May 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Grenier (2008); Thomas Beamish Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition). p 7

- Grenier (2008)

- Salusbury, Expeditions of Honour edited by Rompkey p. 91

- p.8

- Canadian Biography

- John Hamilton's letter to Governor Cornwallis "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-10-20. Retrieved 2014-01-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- See Faragher 262; Griffiths (2005), p. 392; Murdoch (1866), pp. 166-167; Grenier (2008), p. 153; and "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-05-14. Retrieved 2014-02-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- Murdoch (1866), p. 180

- http://www.militaryheritage.com/40th.htm

- A genuine narrative of the transactions in Nova Scotia since the settlement, June 1749, till August the 5th, 1751 : in which the nature, soil, and produce of the country are related, with the particular attempts of the Indians to disturb the colony / by John Wilson p. 15

-

- Atkins puts the month of this raid in July and writes that there were six British attacked, two were scalped and four were taken prisoner and never seen again. Thomas Atkins. History of Halifax City. Brook House Press. 2002 (reprinted 1895 edition). p 334

- Murdoch (1866), p. 225

- "Fort Vieux Logis", Recent Projects Archived May 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2014-07-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)