Fortriu

Fortriu or the Kingdom of Fortriu is the name given by historians to a Pictish kingdom recorded between the 4th and 10th centuries,[1] and often used synonymously with Pictland in general. While traditionally located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, it is more likely to have been located in and around Moray and Easter Ross in the north.

Name

The people of Fortriu left no surviving indigenous writings[2] and the name they used to describe themselves is unrecorded.[3]

The population group was first documented in the late 4th century by the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, who referred to them in Latin as the Verturiones (or Vecturiones).[4] The Latin root verturio has been connected etymologically by John Rhys with the later Welsh word gwerthyr, meaning "fortress",[5] suggesting that both came from a Common Brittonic root vertera, and implying that the group's name meant "Fortress People".[6] A reconstructed form in the Pictish language would be something like *Uerteru.[7]

A connected Old Irish form of the name appears from the 6th to the 10th centuries in the Annals of Ulster and later sources, which contain repeated references to rex Fortrenn, ("the King of Fortriu"), la firu Fortrenn ("the men of Fortriu") and Maigh Fortrenn ("the plain of Fortriu"), alongside references to battles occurring i Fortrinn ("in Fortriu").[8] These are examples of a common pattern of Goidelic languages rendering with an f what in Brittonic languages is U/V, W or Gw.[9] The word Fortriu is a modern reconstruction of a hypothetical nominative form for this word that has survived only in these genitive and dative cases.[10] Anglo-Saxon sources, from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in the 6th century to Bede in the 8th century, refer to the group using the Old English form of the name Wærteras.[11]

Modern scholars writing in English usually refer to the Kingdom using the name Fortriu and the adjective Verturian, and use the name the Wærteras to refer to the people as an ethnic group.[1]

Location

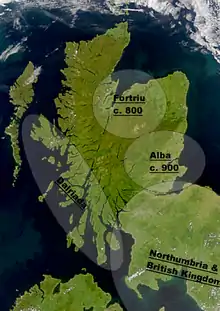

Traditionally the kingdom has been seen as centred on central Scotland, equivalent to the Kingdom of the Southern Picts, with a heartland perhaps in Strathearn. Over the last century or so this has become a scholarly consensus.[12] However, new research by Alex Woolf seems to have destroyed this consensus, if not the idea itself. As Woolf has pointed out, the only basis for it had been that a battle had taken place in Strathearn in which the Men of Fortriu had taken part. This is an unconvincing reason on its own, because there are two Strathearns — one in the south, and one in the north — and, moreover, every battle has to be fought outside the territory of one of the combatants. By contrast, a northern recension of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle makes it clear that Fortriu was north of the Mounth (i.e., the eastern Grampians), in the area visited by Columba.[13] The long poem known as The Prophecy of Berchán, written perhaps in the 12th century, but purporting to be a prophecy made in the Early Middle Ages, says that Dub, King of Scotland was killed in the Plain of Fortriu.[14] Another source, the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba, indicates that King Dub was killed at Forres, a location in Moray.[15] Moreover, additions to the Chronicle of Melrose confirm that Dub was killed by the men of Moray at Forres.[16]

The Prophecy of Berchán states that "Mac Bethad, the glorious king of Fortriu, will take [Scotland]."[17] As Macbeth, King of Scotland may have been Mormaer of Moray before he became King of Scots, it is possible that Fortriu was understood to be interchangeable with Moray in the High Middle Ages. Fortriu is also mentioned as one of the seven ancient Pictish kingdoms in the 13th-century source known as De Situ Albanie.

There can be little or no doubt then that Fortriu centred on northern Scotland. Other Pictish scholars, such as James E. Fraser are now taking it for granted that Fortriu was in the north of Scotland, centred on Moray and Easter Ross, where most early Pictish monuments are located.[1] Hence, it is in these areas that the united kingdom of the Picts originated, perhaps acquiring southern Pictland after the expulsion of the Northumbrians by King Bridei III of the Picts at the Battle of Dun Nechtain in 685 CE.

Relocating Fortriu north of the Mounth increases the importance of the Vikings. The Viking impact on the north was greater than in the south, and in the north, the Vikings actually conquered and made permanent territorial gains. The creation of Alba or the Kingdom of Scotland from Pictland, traditionally associated with a conquest by Kenneth MacAlpin (Old Irish: Cináed mac Ailpín) in 843, can perhaps be better understood in this context.

It appears from a discovery made by Oliver Curran, a Northern Irish historian, that a tribe of the Fortriu were also located at Newry, County Down: according to an 18th-century translation of Ptolemy's map of Ireland they are seen in the wider area marked Voluntii which he says corresponds with the Cruithne (Picts). It is not yet known whether other scholars will be convinced.[18] There have also been Pictish 'Z' rod carvings and a settlement found on Trusty's hill at Gatehouse of Fleet, Dumfries and Galloway. There are also numerous cup and ring carvings and megaliths in the Machars and the Rhins of Galloway hinting at a migration route to Ireland.

See also

Notes

- Fraser 2009, p. 50.

- Woolf 2001, p. 106.

- Woolf 2007, p. 31.

- Woolf 2006, p. 188.

- Watson 2004, p. 69.

- Anderson, Alan Orr; Anderson, Marjorie Ogilvie (1961). Adomnan's Life of Columba. London: Nelson. p. 33. OCLC 669641.

- Woolf 2001, p. 107.

- Woolf 2006, pp. 193, 196.

- Watson 2004, p. 48.

- Watson 2004, p. 68.

- Woolf 2006, pp. 198.

- see virtually any work dealing with the Picts before 2005.

- Woolf 2006, p. 199.

- A. O. Anderson, Early Sources, Vol. I, p. 474.

- A. O. Anderson, Early Sources, Vol. I, p. 473.

- A. O. Anderson, Early Sources, Vol. I, pp. 473–4.

- A. O. Anderson, Early Sources, Vol. I, p. 601.

- His correspondence concerning the find is on-going with the aforementioned Dr Alex Woolf.

References

- Anderson, Alan Orr, Early Sources of Scottish History: AD 500-1286, 2 Vols, (Edinburgh, 1922)

- Foster, Sally M. (2014). Picts, Scots and Gaels — Early Historic Scotland. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 9781780271910.

- Fraser, James (2009). From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748612321.

- Hudson, Benjamin T., Kings of Celtic Scotland, (Westport, 1994)

- Watson, William J. (2004) [1926]. Taylor, Simon (ed.). The Celtic Placenames of Scotland. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 9781841583235.

- Woolf, Alex (2001). "The Verturian Hegemony: A Mirror in the North". In Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (eds.). Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe. Leicester: Leicester University Press. pp. 106–112. ISBN 9780826477651.

- Woolf, Alex (October 2006). "Dén Nechtain, Fortriu and the Geography of the Picts". Scottish Historical Review. 85 (2): 182–201. doi:10.3366/shr.2007.0029. ISSN 0036-9241.

- Woolf, Alex (2007). From Pictland to Alba 789–1070. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748612345.