Franz Xaver Messerschmidt

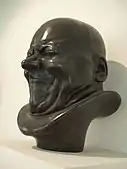

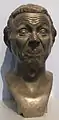

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt (February 6, 1736 – August 19, 1783) was a German-Austrian sculptor most famous for his "character heads", a collection of busts with faces contorted in extreme facial expressions.

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt | |

|---|---|

Self portrait, c. 1780 | |

| Born | February 6, 1736 Swabia, Germany |

| Died | August 19, 1783 (aged 47) Pozsony, Hungary (today Bratislava, Slovakia) |

Early years

Born February 6th 1736 in the southwestern town of Wiesensteig, located in the region of the Swabian Jura Germany. Messerschmidt grew up in the Munich home of his uncle, the sculptor Johann Baptist Straub, who became his first master. He spent two years in Graz, in the workshop of his other maternal uncle, the sculptor Philipp Jakob Straub. At the end of 1755 he matriculated at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, and became a pupil of Jacob Schletterer. Graduated, he got work at the imperial arms collection. Here, in the building's salon in 1760-63 he made his first known works of art, the bronze busts of the imperial couple and reliefs representing the heir of the crown and his wife. With these works he joined the Late Baroque art of courtly representation, which was under the determining influence of Balthasar Ferdinand Moll. To this trend belong two other, larger than lifesize tin statues representing the imperial couple, commissioned by Maria Theresa of Austria and executed between 1764 and 1766. Besides some other portraits he also made works with a religious subject. A number of statues commissioned by the Princess of Savoy have survived as well.

Maturity

The Baroque period of his oeuvre ended in 1769 with a bust of the court physician Gerard van Swieten, commissioned by the Empress. At the same time his first early Neo-Classic works appeared, made—characteristically—for the Academy. To these and later works he applied many experiences gained in 1765 during a study trip to Rome. One of these early, severe heads from the years 1769-70, influenced by Roman republican portraits, represents the well-known doctor Franz Anton Mesmer. At about the same time, in 1770-72 Messerschmidt began to work on his so-called character heads, which it has been argued (notably by Ernst Kris) were connected with certain paranoid ideas and hallucinations from which, at the beginning of the seventies, the master began to suffer. Messerschmidt found himself increasingly at odds with his milieu. His situation worsened to such an extent, that in 1774, when he applied for the newly-vacant office of a leading professor at the Academy, where he had been teaching since 1769, instead of getting it he was expelled from teaching. In a letter to the Empress, Count Kaunitz praised Messerschmidt's abilities, but suggested that the nature of his illness (referred to as a "confusion in the head") would make such an appointment detrimental to the institution.

Later years

Bitter, he left Vienna, moved to his native village, Wiesensteig, and from there in the same year, following an invitation, to Munich. Here he waited two years for a promised commission and for a permanent employment at the Court. In 1777 he went to Pressburg (now Bratislava) where his brother, Johann Adam worked as a sculptor. Here he spent the last six years of his life almost in retirement, on the outskirts of the town. He dedicated himself primarily to his character heads.

The heads

In 1781, German author Friedrich Nicolai visited Messerschmidt at his studio in Pressburg and subsequently published a transcript of their conversation. Nicolai's account of the meeting is a valuable resource, as it is the only contemporary document that details Messerschmidt's reasoning behind the execution of his character heads. Messerschmidt devised a series of pinches he administered to his right lower rib. Observing the resulting facial expressions in a mirror, Messerschmidt then set about recording them in marble and bronze. His intention, he told Nicolai, was to represent the 64 "canonical grimaces" of the human face using himself as a template.

During the course of the discussion, Messerschmidt went on to explain his interest in necromancy and the arcane, and how this also inspired his character heads. Messerschmidt was a keen disciple of Hermes Trismegistus (Nicolai noted that among the few possessions that littered Messerschmidt's workshop was a copy of an illustration featuring Trismegistus) and abided by his teachings regarding the pursuit of "universal balance": a forerunner to the principles of the Golden ratio. As a result, Messerschmidt claimed that his character heads had aroused the anger of "the Spirit of Proportion", an ancient being who safe-guarded this knowledge. The spirit visited him at night, and forced him to endure humiliating tortures. One of Messerschmidt's most famous heads (The Beaked) was apparently inspired by one of these encounters.

The Laughter Kept Back

The Laughter Kept Back A Grievously Wounded Man

A Grievously Wounded Man The Satirist

The Satirist The Yawner

The Yawner A Hypocrite and Slanderer

A Hypocrite and Slanderer The Ultimate Simpleton

The Ultimate Simpleton Afflicted with Constipation

Afflicted with Constipation An Intentional Wag

An Intentional Wag.png.webp) A Hypochondriac (Character Head No. 36), about 1775-80, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

A Hypochondriac (Character Head No. 36), about 1775-80, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Sources

- Albert Ilg (1885), "Messerschmidt, Franz Xaver", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German), 21, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 497–499

- Michael Krapf, Almut Krapf-Weiler, Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, Hatje Cantz Publishers, ISBN 3-7757-1246-1, 2003.

- Maria Pötzl-Malikova (1994), "Messerschmidt, Franz Xaver", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 17, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 219–220; (full text online)

- Maria Pötzl-Malíková. "Messerschmidt, Franz Xaver." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, (accessed January 10, 2012; subscription required).

- Maria Pötzl Malikova, Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, Jugend and Volk Publishing Company, 1982. ISBN 3-7141-6794-3. Translation into English: Herb Ranharter, 2006

- Theodor Schmid, 49 Köpfe, Theodor Schmid Verlag, ISBN 3-906566-61-7, 2004.

- Franz Xaver Messerschmidt 1736-1783. From Neoclassicism to Expressionism, edited by Maria Pötzl Malikova and Guilhem Scherf, Officina Libraria/Neue Galerie/Musée du Louvre, ISBN 978-88-89854-54-9, 2010.

- Eric R. Kandel,The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain, from Vienna 1900 to the Present, Random House Publishing Group, ISBN 978-1-4000-6871-5, 2012.

- Michael Yonan, Messerschmidt's Character Heads: Maddening Sculpture and the Writing of Art History, Routledge, ISBN 9781138213432, 2018

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Franz Xaver Messerschmidt. |

- Entry for Franz Xaver Messerschmidt on the Union List of Artist Names

- Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, A Documentary Film by Hakan Topal

- Collection of busts held in Slovak national gallery

- Biography of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt from the Web Gallery of Art

- Website concerning Messerschmidt with extended bibliography

- Forbes article on Messerschmidt at the Getty Museum

- Information on the 2010-11 exhibition of Messerschmidt's work at the Neue Galerie and the Louvre