Hermes Trismegistus

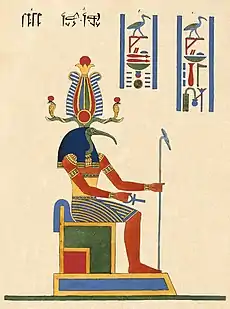

Hermes Trismegistus (from Ancient Greek: Ἑρμῆς ὁ Τρισμέγιστος, "Hermes the Thrice-Greatest"; Classical Latin: Mercurius ter Maximus) is a legendary Hellenistic figure that originated as a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth.[1] He is the purported author of the Hermetica, a widely diverse series of ancient and medieval texts that lay the basis of various philosophical systems known as Hermeticism.

| Part of a series on |

| Hermeticism |

|---|

|

| Mythology |

|

Hermetic arts |

| Hermetic writings |

|

Related historical figures (ancient and medieval) |

|

|

Related historical figures (early modern) |

| Modern offshoots |

Origin and identity

Hermes Trismegistus may be associated with the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth.[2] Greeks in the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt recognized the equivalence of Hermes and Thoth through the interpretatio graeca.[3] Consequently, the two gods were worshiped as one, in what had been the Temple of Thoth in Khemenu, which was known in the Hellenistic period as Hermopolis.[4]

Hermes, the Greek god of interpretive communication, was combined with Thoth, the Egyptian god of wisdom. The Egyptian priest and polymath Imhotep had been deified long after his death and therefore assimilated to Thoth in the classical and Hellenistic periods.[5] The renowned scribe Amenhotep and a wise man named Teôs were coequal deities of wisdom, science, and medicine; and, thus, they were placed alongside Imhotep in shrines dedicated to Thoth–Hermes during the Ptolemaic Kingdom.[6]

A Mycenaean Greek reference to a deity or semi-deity called ti-ri-se-ro-e (Linear B: 𐀴𐀪𐀮𐀫𐀁; Tris Hḗrōs, "thrice or triple hero")[7] was found on two Linear B clay tablets at Pylos[8] and could be connected to the later epithet "thrice great", Trismegistos, applied to Hermes/Thoth. On the aforementioned PY Tn 316 tablet—as well as other Linear B tablets found in Pylos, Knossos, and Thebes—there appears the name of the deity "Hermes" as e-ma-ha (Linear B: 𐀁𐀔𐁀), but not in any apparent connection with the "Trisheros". This interpretation of poorly understood Mycenaean material is disputed, since Hermes Trismegistus is not referenced in any of the copious sources before he emerges in Hellenistic Egypt.

Cicero enumerates several deities referred to as "Hermes": a "fourth Mercury (Hermes) was the son of the Nile, whose name may not be spoken by the Egyptians"; and "the fifth, who is worshiped by the people of Pheneus [in Arcadia], is said to have killed Argus Panoptes, and for this reason to have fled to Egypt, and to have given the Egyptians their laws and alphabet: he it is whom the Egyptians call Theyt".[9] The most likely interpretation of this passage is as two variants on the same syncretism of Greek Hermes and Egyptian Thoth (or sometimes other gods): the fourth (where Hermes turns out "actually" to have been a "son of the Nile," i.e. a native god) being viewed from the Egyptian perspective, the fifth (who went from Greece to Egypt) being viewed from the Greek-Arcadian perspective. Both of these early references in Cicero (most ancient Trismegistus material is from the early centuries AD) corroborate the view that Thrice-Great Hermes originated in Hellenistic Egypt through syncretism between Greek and Egyptian gods (the Hermetica refer most often to Thoth and Amun).[10]

The Hermetic literature among the Egyptians, which was concerned with conjuring spirits and animating statues, inform the oldest Hellenistic writings on Greco-Babylonian astrology and on the newly developed practice of alchemy.[11] In a parallel tradition, Hermetic philosophy rationalized and systematized religious cult practices and offered the adept a means of personal ascension from the constraints of physical being. This latter tradition has led to the confusion of Hermeticism with Gnosticism, which was developing contemporaneously.[12]

As a divine source of wisdom, Hermes Trismegistus was credited with tens of thousands of highly esteemed writings, which were reputed to be of immense antiquity. Clement of Alexandria was under the impression that the Egyptians had forty-two sacred writings by Hermes, writings that detailed the training of Egyptian priests. Siegfried Morenz has suggested, in Egyptian Religion: "The reference to Thoth's authorship... is based on ancient tradition; the figure forty-two probably stems from the number of Egyptian nomes, and thus conveys the notion of completeness." The neoplatonic writers took up Clement's "forty-two essential texts".

The Hermetica is a category of papyri containing spells and initiatory induction procedures. The dialogue called the Asclepius (after the Greek god of healing) describes the art of imprisoning the souls of demons or of angels in statues with the help of herbs, gems, and odors, so that the statue could speak and engage in prophecy. In other papyri, there are recipes for constructing such images and animating them, such as when images are to be fashioned hollow so as to enclose a magic name inscribed on gold leaf.

Thrice Great

Fowden asserts that the first datable occurrences of the epithet "thrice great" are in the Legatio of Athenagoras of Athens and in a fragment from Philo of Byblos, circa AD 64–141.[13] However, in a later work, Copenhaver reports that this epithet is first found in the minutes of a meeting of the council of the Ibis cult, held in 172 BC near Memphis in Egypt.[14] Hart explains that the epithet is derived from an epithet of Thoth found at the Temple of Esna, "Thoth the great, the great, the great."[3] The date of Hermes Trismegistus's sojourn in Egypt during his last incarnation is not now known, but it has been fixed at the early days of the oldest dynasties of Egypt, long before the days of Moses. Some authorities regard him as a contemporary of Abraham, and claim that Abraham acquired a portion of his mystical knowledge from Hermes himself (Kybalion).

Many Christian writers, including Lactantius, Augustine, Marsilio Ficino, Campanella, and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, as well as Giordano Bruno, considered Hermes Trismegistus to be a wise pagan prophet who foresaw the coming of Christianity.[15][16] They believed in the existence of a prisca theologia, a single, true theology that threads through all religions. It was given by God to man in antiquity[17][18] and passed through a series of prophets, which included Zoroaster and Plato. In order to demonstrate the verity of the prisca theologia, Christians appropriated the Hermetic teachings for their own purposes. By this account, Hermes Trismegistus was either a contemporary of Moses,[19] or the third in a line of men named Hermes, i.e. Enoch, Noah, and the Egyptian priest king who is known to us as Hermes Trismegistus[20] on account of being the greatest priest, philosopher, and king.[20][21]

This last account of how Hermes Trismegistus received that epithet is derived from statements in the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, that he knows the three parts of the wisdom of the whole universe.[22]

Another explanation, in the Suda (10th century), is that "He was called Trismegistus on account of his praise of the trinity, saying there is one divine nature in the trinity."[23]

Hermetic writings

The Asclepius and the Corpus Hermeticum are the most important of the Hermetica, the surviving writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus. During the Renaissance, it was accepted that Hermes Trismegistus was a contemporary of Moses. However, after Casaubon's dating of the Hermetic writings as being no earlier than the second or third century AD, the whole of Renaissance Hermeticism collapsed.[24] As to their actual authorship:

... they were certainly not written in remotest antiquity by an all wise Egyptian priest, as the Renaissance believed, but by various unknown authors, all probably Greeks, and they contain popular Greek philosophy of the period, a mixture of Platonism and Stoicism, combined with some Jewish and probably some Persian influences.[25]

Hermetic revival

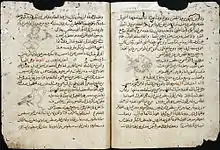

During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance the Hermetica enjoyed great prestige and were popular among alchemists. Hermes was also strongly associated with astrology, for example by the influential Islamic astrologer Abu Ma'shar (787–886).[26] The "hermetic tradition" consequently refers to alchemy, magic, astrology, and related subjects. The texts are usually divided into two categories: the philosophical and the technical hermetica. The former deals mainly with philosophy, and the latter with practical magic, potions, and alchemy. The expression "hermetically sealed" comes from the alchemical procedure to make the Philosopher's Stone. This required a mixture of materials to be placed in a glass vessel which was sealed by fusing the neck closed, a procedure known as the Seal of Hermes. The vessel was then heated for 30 to 40 days.[27]

The classical scholar Isaac Casaubon, in De rebus sacris et ecclesiasticis exercitationes XVI (1614), showed, through an analysis of the Greek language used in the texts, that those texts believed to be of ancient origin were in fact much more recent: most of the philosophical Corpus Hermeticum can be dated to around AD 300. However, the 17th century scholar Ralph Cudworth argued that Casaubon's allegation of forgery could only be applied to three of the seventeen treatises contained within the Corpus Hermeticum.[28]

Islamic tradition

Sayyid Ahmed Amiruddin has pointed out that early Christian and Islamic traditions call Hermes Trismegistus the builder of the Pyramids of Giza[29] and has a major place in Islamic tradition. He writes, "Hermes Trismegistus is mentioned in the Quran in verse 19:56-57: 'Mention, in the Book, Idris, that he was truthful, a prophet. We took him up to a high place'". The Jabirian corpus contains the oldest documented source for the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, translated by Jābir ibn Hayyān (Geber) for the Hashemite Caliph of Baghdad Harun al-Rashid the Abbasid. Jābir ibn Hayyān, a Shiite, identified as Jābir al-Sufi, was a student of Ja'far al-Sadiq, Husayn ibn 'Ali's great grandson. Thus, for the Abbasid's and the Alid's, the writings of Hermes Trismegistus were considered sacred, as an inheritance from the Ahl al-Bayt and the Prophets. These writings were recorded by the Ikhwan al-Safa, and subsequently translated from Arabic into Persian, Turkish, Hebrew, Russian, and English. In these writings, Hermes Trismegistus is identified as Idris, the infallible Prophet who traveled to outer space from Egypt, and to heaven, whence he brought back a cache of objects from the Eden of Adam and the Black Stone from where he landed on earth in India.[30]

According to ancient Arab genealogists, the Prophet Muhammad, who is also believed to have traveled to the heavens on the night of Isra and Mi'raj, is a direct descendant of Hermes Trismegistus. Ibn Kathir said, "As for Idris... He is in the genealogical chain of the Prophet Muhammad, except according to one genealogist... Ibn Ishaq says he was the first who wrote with the Pen. There was a span of 380 years between him and the life of Adam. Many of the scholars allege that he was the first to speak about this, and they call him Thrice-Great Hermes [Hermes Trismegistus]".[30] Ahmad al-Buni considered himself a follower of the hermetic teachings; and his contemporary Ibn Arabi mentioned Hermes Trismegistus in his writings. The Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya of Ibn Arabi speaks of Hermes's travels to "vast cities (outside earth), possessing technologies far superior than ours"[31] and meeting with the Twelfth Imam, the Ninth (generation) from the Third (al-Husayn the third Imam) (referring here to the Masters of Wisdom from the Emerald Tablet), who also ascended to the heavens, and is still alive like his ancestor Hermes Trismegistus".[32]

A late Arabic writer wrote of the Sabaeans that their religion had a sect of star worshipers who held their doctrine to come from Hermes Trismegistus through the prophet Adimun.[33]

Antoine Faivre, in The Eternal Hermes (1995), has pointed out that Hermes Trismegistus has a place in the Islamic tradition, although the name Hermes does not appear in the Qur'an. Hagiographers and chroniclers of the first centuries of the Islamic Hegira quickly identified Hermes Trismegistus with Idris,[34] the nabi of surahs 19.57 and 21.85, whom the Arabs also identified with Enoch (cf. Genesis 5.18–24). Idris/Hermes was termed "Thrice-Wise" Hermes Trismegistus because he had a threefold origin. The first Hermes, comparable to Thoth, was a "civilizing hero", an initiator into the mysteries of the divine science and wisdom that animate the world; he carved the principles of this sacred science in hieroglyphs. The second Hermes, in Babylon, was the initiator of Pythagoras. The third Hermes was the first teacher of alchemy. "A faceless prophet," writes the Islamicist Pierre Lory, "Hermes possesses no concrete or salient characteristics, differing in this regard from most of the major figures of the Bible and the Quran."[35] A common interpretation of the representation of "Trismegistus" as "thrice great" recalls the three characterizations of Idris: as a messenger of god, or a prophet; as a source of wisdom, or hikmet (wisdom from hokmah); and as a king of the world order, or a "sultanate". These are referred to as müselles bin ni'me.

Baháʼí writings

Bahá'u'lláh, founder of the Baháʼí Faith, identifies Idris with Hermes in his Tablet on the Uncompounded Reality.[36] He does not, however, specifically name Idris as the prophet of the Sabians.

New Age revival

Modern occultists claim that some Hermetic texts may be of Pharaonic origin, and that the legendary "forty-two essential texts" that contain the core Hermetic religious beliefs and philosophy of life, remain hidden in a secret library.[37]

The book Kybalion, by "The Three Initiates", addresses Hermetic principles.[38]

Within the occult tradition, Hermes Trismegistus is associated with several wives, and more than one son who took his name, as well as more than one grandson.[39] This repetition of given name and surname throughout the generations may at least partially account for the legend of his longevity, especially as it is believed that many of his children pursued careers as priests in mystery religions.[39]

References

- A survey of the literary and archaeological evidence for the background of Hermes Trismegistus in the Greek Hermes and the Egyptian Thoth may be found in Bull, Christian H. 2018. The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom. Leiden: Brill, pp. 33-96.

- Budge, E.A. Wallis (1904). The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1. pp. 414–5.

- Hart, G., The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, 2005, Routledge, second edition, Oxon, p 158

- Bailey, Donald, "Classical Architecture" in Riggs, Christina (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Roman Egypt (Oxford University Press, 2012), p. 192.

- Artmann, Benno (22 November 2005). "About the Cover: The Mathematical Conquest of the Third Dimension" (PDF). Bulletin (New Series) of the American Mathematical Society. 43 (2): 231. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-06-01111-6. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- Thoth or the Hermes of Egypt: A Study of Some Aspects of Theological Thought in Ancient Egypt, p.166–168, Patrick Boylan, Oxford University Press, 1922.

- "Heroes and HERO cults I | V(otum) S(olvit) L(ibens) M(erito)". Dismanibus156.wordpress.com. 2008-05-14. Retrieved 2015-06-25.

- Archived September 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- De natura deorum III, Ch. 56

- "Cicero: De Natura Deorum III". Thelatinlibrary.com. Retrieved 2015-06-25.

- Fowden 1993: pp65–68

- "Stages of Ascension in Hermetic Rebirth". Esoteric.msu.edu. Retrieved 2015-06-25.

- Fowden, G., "The Egyptian Hermes", Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1987, p 216

- Copenhaver, B. P., "Hermetica", Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992, p xiv.

- Heiser, James D. (2011). Prisci Theologi and the Hermetic Reformation in the Fifteenth Century (1st ed.). Malone, Tex.: Repristination Press. ISBN 978-1-4610-9382-4.

- Jafar, Imad (2015). "Enoch in the Islamic Tradition". Sacred Web: A Journal of Tradition and Modernity. XXXVI.

- Yates, F., "Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition", Routledge, London, 1964, pp 14–18 and pp 433–434

- Hanegraaff, W. J., "New Age Religion and Western Culture", SUNY, 1998, p 360

- Yates, F., "Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition", Routledge, London, 1964, p 27 and p 293

- Yates, F., "Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition", Routledge, London, 1964, p52

- Copenhaver, B.P., "Hermetica", Cambridge University Press, 1992, p xlviii

- (Scully p. 322)

- Copenhaver, Hermetica, p. xli

- Haanegraaff, W. J., New Age Religion and Western Culture, Brill, Leiden, New York, 1996, p 390

- (Yates Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition pp. 2–3)

- Van Bladel, Kevin 2009. The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 122ff.

- Principe, L. M., The Secrets of Alchemy, 2013, University of Chicago Press, p 123

- Cudworth, Ralph - The True Intellectual System of the Universe. First American Edition by Thomas Birch, 1837. Available at Googlebooks.

- "The Tombs of Prophets Seth and Idris: The Great Pyramids of Giza". Sayyid Amiruddin. 2013-01-02. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis, p.46. Wheeler, Brannon. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2002

- Thomson, Ahmad. Dajjal, page 10

- "Sayyid A. Amiruddin | An Authorized Khalifah of H.E Mawlana Shaykh Nazim Adil al-Haqqani". Ahmedamiruddin.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2015-06-25.

- Stapleton, H.E.; R.F. Azo & M.H. Husein (1927). Chemistry in Iraq and Persia in the Tenth Century AD: Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Volume 8. Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal. pp. 398–403.

- Kevin Van Bladel, The Arabic Hermes. From pagan sage to prophet of science, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 168 "Abu Mas'har’s biography of Hermes, written approximately between 840 and 860, would establish it as common knowledge."

- (Faivre 1995 pp. 19–20)

- "Hermes Trismegistus and Apollonius of Tyana in the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh". Bahai-library.com. Retrieved 2015-06-25.

- Clive, Prince (2016-05-05). The forbidden universe. ISBN 9781472124784. OCLC 952966194.

- Initiates., Three (c. 2000). The kybalion : a study of the hermetic philosophy of ancient Egypt and Greece. Yogi Publication Society, Masonic Temple. ISBN 9780911662252. OCLC 48179182.

- Jackson, Samuel Macauley (2017). Concise Dictionary of Religious Knowledge and Gazetteer. Classic Reprint Series. Forgotten Books. ISBN 9781334944413. OCLC 984110903.

Bibliography

- Aufrère, Sydney H. (2008) (in French). Thot Hermès l'Egyptien: De l'infiniment grand à l'infiniment petit. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2296046399.

- Bull, Christian H. 2018. The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom. Leiden: Brill. (the standard reference work on the subject)

- CACIORGNA, Marilena e GUERRINI, Roberto: Il pavimento del duomo di Siena. L'arte della tarsia marmorea dal XIV al XIX secolo fonti e simologia. Siena 2004.

- CACIORGNA, Marilena: Studi interdisciplinari sul pavimento del duomo di Siena. Atti el convegno internazionale di studi chiesa della SS. Annunziata 27 e 28 settembre 2002. Siena 2005.

- Copenhaver, Brian P. (1995). Hermetica: the Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a new English translation, with notes and introduction, Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995 ISBN 0-521-42543-3.

- Ebeling, Florian, The secret history of Hermes Trismegistus: Hermeticism from ancient to modern times [Translated from the German by David Lorton] (Cornell University Press: Ithaca, 2007), ISBN 978-0-8014-4546-0.

- Festugière, A.-J.,La révélation d'Hermès Trismégiste. 2e éd., 3 vol., Paris 1981.

- Fowden, Garth, 1986. The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Princeton University Press, 1993): deals with Thoth (Hermes) from his most primitive known conception to his later evolution into Hermes Trismegistus, as well as the many books and scripts attributed to him.

- Hornung, Erik (2001). The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West. Translated by David Lorton. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801438470.

- Lupini, Carmelo, s.v. Ermete Trismegisto in "Dizionario delle Scienze e delle Tecniche di Grecia e Roma", Roma 2010, vol. 1.

- Merkel, Ingrid and Allen G. Debus, 1988. Hermeticism and the Renaissance: intellectual history and the occult in early modern Europe Folger Shakespeare Library ISBN 0-918016-85-1

- Van Bladel, Kevin (2009). The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537613-5 (the standard reference for Hermes in the Arabic-Islamic world)

- Van den Kerchove, Anna 2012. La voie d’Hermès: Pratiques rituelles et traités hermétiques. Leiden: Brill.

- Yates, Frances A., Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. University of Chicago Press, 1964. ISBN 0-226-95007-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hermes Trismegistus. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Hermes Trismegistus |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Hermes Trismegistus |

| Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Corpus Hermeticum along with the complete text of G.R.S. Mead's classic work, Thrice Greatest Hermes

- Hermetic Research is a portal on Hermetic study and discussion

- Dan Merkur, "Stages of Ascension in Hermetic Rebirth"

- Asclepius— Latin text of the edition Paris: Henricus Stephanus 1505.

- Pimander—Latin translation by Marsilio Ficino, Milano: Damianus de Mediolano, 1493.

- THE DIVINE PYMANDER of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus in English

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries—High resolution images of works by Hermes Trismegistus in JPEG and TIFF format.

- "The Great Pyramid and the 153 Fish in the Net"—Mathematical Explanation of where he got his name