From Russia, with Love (novel)

From Russia, with Love is the fifth novel by the English author Ian Fleming to feature his fictional British Secret Service agent James Bond. Fleming wrote the story in early 1956 at his Goldeneye estate in Jamaica; at the time he thought it might be his final Bond book. The novel was first published in the United Kingdom by Jonathan Cape on 8 April 1957.

First edition cover | |

| Author | Ian Fleming |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Richard Chopping Devised by Ian Fleming |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Series | James Bond |

| Genre | Spy fiction |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape |

Publication date | 8 April 1957 (hardback) |

| Pages | 253 (first edition) |

| Preceded by | Diamonds Are Forever |

| Followed by | Dr. No |

The story centres on a plot by SMERSH, the Soviet counter-intelligence agency, to assassinate Bond in such a way as to discredit both him and his organisation. As bait, the Russians use a beautiful cipher clerk and the Spektor, a Soviet decoding machine. Much of the action takes place in Istanbul and on the Orient Express. The book was inspired by Fleming's visit to Turkey on behalf of The Sunday Times to report on an Interpol conference; he returned to Britain by the Orient Express. From Russia, with Love deals with the East–West tensions of the Cold War, and the decline of British power and influence in the post-Second World War era.

From Russia, with Love received broadly positive reviews at the time of publication. The book's sales were boosted by an advertising campaign that played upon a visit by the British Prime Minister Anthony Eden to the Goldeneye estate, and the publication of an article in Life, which listed From Russia, with Love as one of US President John F. Kennedy's ten favourite books. The story was serialised in the Daily Express newspaper, first in an abridged, multi-part form and then as a comic strip. In 1963 it was adapted into the second film in the Bond series, starring Sean Connery.

Plot

Ian Fleming, From Russia, with Love, Author's note[1]

SMERSH, the Soviet counterintelligence agency, plans to commit a grand act of terrorism in the intelligence field. For this, it targets British secret service agent James Bond. Due in part to his role in the defeat of SMERSH agents Le Chiffre, Mr. Big and Hugo Drax, Bond has been listed as an enemy of the Soviet state, and a "death warrant" is issued for him. His death is planned to precipitate a major sex scandal, which will run in the world press for months and leave both his and his service's reputations in tatters.

Donovan "Red" Grant, a psychopathic British Army deserter whose homicidal urges coincide with the full moon, is assigned as Bond's killer. Kronsteen, SMERSH's chess-playing master planner, and Colonel Rosa Klebb, the head of Operations and Executions, devise the operation. They instruct an attractive young cipher clerk, Corporal Tatiana Romanova, to falsely defect from her post in Istanbul and claim to have fallen in love with Bond after seeing a photograph of him. As an added lure for Bond, Romanova will provide the British with a Spektor, a Russian decoding device much coveted by MI6. She is not told the details of the plan.

The offer of defection is received by MI6 in London, ostensibly from Romanova, but is conditional that Bond collects her and the Spektor from Istanbul. MI6 is unsure of Romanova's motive, but the prize of the Spektor is too tempting to ignore; Bond's superior, M, orders him to go to Turkey. Once there, Bond forms a comradeship with Darko Kerim, head of the British service's station in Turkey. Bond meets Romanova, and they plan their route out of Turkey with the Spektor. He and Kerim believe her story, and the three board the Orient Express. Kerim quickly discovers three Russian MGB agents on board, travelling incognito. He uses bribes and trickery to have two of them taken off the train, but he is later found dead in his compartment with the third MGB agent's body.

At Trieste, a man introduces himself as Captain Nash, a fellow MI6 agent, and Bond presumes M has sent him as added protection for the rest of the trip. Romanova is suspicious of Nash, but Bond reassures her that the man is from his own service. After dinner, at which Nash has drugged Romanova, they rest. Nash later wakes Bond, holding him at gunpoint, and reveals himself as the killer Grant. Instead of killing Bond immediately, he describes SMERSH's plan. He is to shoot both of them, throw Romanova's body out the window, and plant a film of their love-making in her luggage; in addition, the Spektor is booby-trapped to explode when examined. As Grant talks, Bond places his metal cigarette case between the pages of a book he holds in front of him, positioning it in front of his heart to stop the bullet. After Grant fires, Bond collapses to the floor and, when Grant steps over him, he attacks and kills the assassin. Bond and Romanova escape.

Later, in Paris, after successfully delivering Romanova and the booby-trapped Spektor to his superiors, Bond meets Rosa Klebb. She is captured but manages to kick Bond with a poisoned blade concealed in her shoe; the story ends with Bond fighting for breath and falling to the floor.

Background and writing history

By January 1956, Ian Fleming had published three novels—Casino Royale in 1953, Live and Let Die in 1954 and Moonraker in 1955. A fourth, Diamonds Are Forever, was being edited and prepared for production.[2][3][lower-alpha 1] That month Fleming travelled to his Goldeneye estate in Jamaica to write From Russia, with Love. He followed his usual practice, which he later outlined in Books and Bookmen magazine: "I write for about three hours in the morning ... and I do another hour's work between six and seven in the evening. I never correct anything and I never go back to see what I have written ... By following my formula, you write 2,000 words a day."[5] He returned to London in March that year with a 228-page first-draft manuscript[6] that he subsequently altered more heavily than any of his other works.[7][8] One of the significant re-writes changed Bond's fate; Fleming had become disenchanted with his books[9] and wrote to his friend, the American author Raymond Chandler: "My muse is in a very bad way ... I am getting fed up with Bond and it has been very difficult to make him go through his tawdry tricks."[10] Fleming re-wrote the end of the novel in April 1956 to make Klebb poison Bond, which allowed him to finish the series with the death of the character if he wanted.

Breathing became difficult. Bond sighed to the depth of his lungs. He clenched his jaws and half closed his eyes, as people do when they want to hide their drunkenness. ... He prised his eyes open. ... Now he had to gasp for breath. Again his hand moved up towards his cold face. He had an impression of Mathis starting towards him. Bond felt his knees begin to buckle ... [he] pivoted slowly on his heel and crashed head-long to the wine-red floor.

From Russia, with Love, novel's closing lines

Fleming's first draft ended with Bond and Romanova enjoying a romance.[11] By January 1957 Fleming had decided he would write another story, and began work on Dr. No in which Bond recovers from his poisoning and is sent to Jamaica.[12]

Fleming's trip to Istanbul in June 1955 to cover an Interpol conference for The Sunday Times was a source of much of the background information in the story.[13] While there he met the Oxford-educated ship owner Nazim Kalkavan, who became the model for Darko Kerim;[14] Fleming took down many of Kalkavan's conversations in a notebook, and used them verbatim in the novel.[13][lower-alpha 2]

Although Fleming did not date the event within his novels, John Griswold and Henry Chancellor — both of whom wrote books for Ian Fleming Publications—have identified different timelines based on events and situations within the novel series as a whole. Chancellor put the events of From Russia, with Love in 1955; Griswold considers the story to have taken place between June and August 1954.[16][17] In the novel, General Grubozaboyschikob of the MGB refers to the Istanbul pogrom, the Cyprus Emergency, and the "revolution in Morocco" (a reference to the massive demonstrations in Morocco that forced France to grant independence in November 1955) as recent events.[18]

In August 1956, for fifty guineas, Fleming commissioned Richard Chopping to provide the art for the cover, based on Fleming's design; the result won a number of prizes.[19][20] After Diamonds Are Forever had been published in March 1956, Fleming received a letter from a thirty-one-year-old Bond enthusiast and gun expert, Geoffrey Boothroyd, criticising the author's choice of firearm for Bond.

I wish to point out that a man in James Bond's position would never consider using a .25 Beretta. It's really a lady's gun—and not a very nice lady at that! Dare I suggest that Bond should be armed with a .38 or a nine millimetre—let's say a German Walther PPK? That's far more appropriate.[21]

Boothroyd's suggestions came too late to be included in From Russia, with Love, but one of his guns—a .38 Smith & Wesson snubnosed revolver modified with one third of the trigger guard removed—was used as the model for Chopping's image.[22] Fleming later thanked Boothroyd by naming the armourer in Dr. No Major Boothroyd.[23]

Development

Plot inspirations

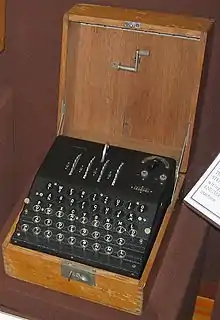

As with several of his works, Fleming appropriated the names or backgrounds of people he knew or had heard of for the story's characters: Red Grant, a Jamaican river guide—whom Fleming's biographer Andrew Lycett described as "a cheerful, voluble giant of villainous aspect"—was used for the half-German, half-Irish assassin.[24][25] Rosa Klebb was partly based on Colonel Rybkina, a real-life member of the Lenin Military-Political Academy about whom Fleming had written an article for The Sunday Times.[26][27] The Spektor machine used as the bait for Bond was not a Cold War device, but had its roots in the Second World War Enigma machine, which Fleming had tried to obtain while serving in the Naval Intelligence Division.[28]

The idea of the Orient Express came from two sources: Fleming had returned from the Istanbul conference in 1955 by the train, but found the experience drab, partly because the restaurant car was closed.[14][29] He also knew of the story of Eugene Karp and his journey on the Orient Express: Karp was a US naval attaché and intelligence agent based in Budapest who, in February 1950, took the Orient Express from Budapest to Paris, carrying a number of papers about blown US spy networks in the Eastern Bloc. Soviet assassins were already on the train. The conductor was drugged and Karp's body was found shortly afterwards in a railway tunnel south of Salzburg.[30] Fleming had a long-standing interest in trains and, following his involvement in a near-fatal crash in 1927, associated them with danger; they also feature in Live and Let Die, Diamonds Are Forever and The Man with the Golden Gun.[31]

Fleming had served in Naval Intelligence in World War Two, but he had never seen action as he knew far too much to run the risk of him being captured. In September 1955, Fleming visited Istanbul, where he witnessed first-hand the bloody pogrom against the Greek, Armenian and Jewish communities organised by the Turkish prime minister Adnan Menderes on 6-7 September 1955.[32] Fleming seems to have believed when he arrived in Istanbul of the success of the Kemalist project, writing “Obedient to the undying memory of Atatürk, Turkey has continued to mould her destiny away from East and towards the West, perhaps in defiance of her stars and certainly in defiance of her true personality, which is at least three-quarters oriental."[32] Fleming's biographer, John Pearson, wrote that in Istanbul "Fleming the symmetrist had seen real violence at last" as ethnic Greeks were lynched by Turkish mobs while hundreds of women and boys were gang-raped in the streets.[32] Fleming described the pogrom as "mobs went howling through the streets, each under its streaming red flag with the white star and sickle moon" and that he had returned to his hotel "nauseated" by what he had seen.[32]

Though in the novel Fleming repeated the absurd claim made by Menderes that the Turkish government had nothing to do with the pogrom, which Menderes instead claimed was the work of Soviet agents, the violence he had seen in Istanbul in 1955 reflected his picture of the city.[32] In From Russia, with Love, Fleming wrote: "Istanbul was a town the centuries had so drenched in blood and violence that, when daylight went out, the ghosts of its dead were its only population."[32] In the novel, Istanbul is portrayed as a threatening and dangerous city that Bond "would be glad to get out of alive".[32] For Fleming, the 1955 pogrom was an expression of the "true personality" of Turkey as he put it in his report in the Sunday Times about the pogrom, which despite the modernization and Westernization started by Mustafa Kemal in the 1920s, was still fundamentally Ottoman and anti-Western.[32] In the novel, all the Westernization under the Turkish republic is only superficial and the Turks are still essentially savages.[32]

The cultural historian Jeremy Black points out that From Russia, with Love was written and published at a time when tensions between East and West were on the rise and public awareness of the Cold War was high. A joint British and American operation to tap into landline communication of the Soviet Army headquarters in Berlin using a tunnel into the Soviet-occupied zone had been publicly uncovered by the Soviets in April 1956. The same month the diver Lionel Crabb had gone missing on a mission to photograph the propeller of the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze while the ship was moored in Portsmouth Harbour, an incident that was much reported and discussed in British newspapers. In October and November that year a popular uprising in Hungary was repressed by Soviet forces.[33]

Characters

To make Bond a more rounded character, Fleming put further aspects of his personality into his creation. The journalist and writer Matthew Parker observes that Bond's "physical and mental ennui" is a reflection of Fleming's poor health and low spirits when he wrote the book.[34][35] The early depictions of Bond were based on earlier literary characters. In New Statesman, the journalist William Cook writes of the early Bond:

James Bond is the culmination of an important but much-maligned tradition in English literature. As a boy, Fleming devoured the Bulldog Drummond tales of Lieutenant Colonel Herman Cyril McNeile (aka "Sapper") and the Richard Hannay stories of John Buchan. His genius was to repackage these antiquated adventures to fit the fashion of postwar Britain ... In Bond, he created a Bulldog Drummond for the jet age.[36]

Following on from the character development of Bond in his previous four novels, Fleming adds further background to Bond's private life, largely around his home life and personal habits, with Bond's introduction to the story seeing him at breakfast with his housekeeper, May.[37] The novelist Raymond Benson—who later wrote a series of Bond novels—sees aspects of self-doubt entering Bond's mind with the "soft" life he has been leading when he is introduced in the book. Benson identifies Bond's fear when the flight to Istanbul encounters severe turbulence from a storm, and notes Bond's apparent nervousness when he first meets Romanova; he seems concerned and guilty about his mission.[38] The other characters in the book are also well developed, according to Benson. He considers that the head of the Turkish office, Darko Kerim Bey, is "one of Fleming's more colourful characters"; Kerim is a similar type of dependable and appealing ally that Fleming also created with Quarrel (in Live and Let Die) and Colombo (in the short story "Risico").[39] Parker considers that Kerim is "an antidote" to Bond's lethargy,[10] while the essayist Umberto Eco sees the character as having some of the moral qualities of the villains in the series, but that those qualities are used in support of Bond.[40][41]

The American scholar Sean Singer accused Fleming of racism with the character of Kerim, who has a Turkish father and an English mother, which to a certain extent makes him better than the Turks.[32] When Kerim meets Bond, his handshake is described: "It was a strong Western handful of operative fingers—not the banana skin handshake of the East that makes you want to wipe your fingers on your coattails."[32] Because of his English mother, Bond considers Kerim to be much better than the "furtive, stunted little men" who live in Turkey.[32] Through Kerim is presented as a favorable character, Bond reflects that he does not belong "outside his territory."[32] Singer wrote that for all the positive aspects of Kerim that are portrayed in the book, "...the hierarchical nature of Bond's relationship with Darko Kerim is inescapable, despite their affection for one another."[32] Fleming uses the character of Kerim as both a symbol of the Kemalist project and as a way to criticise it as Kerim often makes disparaging remarks about Turks, whom he claims are not suited for Western values.[32]

From Russia, with Love is one of the few stories by Fleming in which the Soviets are the main enemy,[42] although Eco considers Bond's Russian opponents "so monstrous, so improbably evil that it seems impossible to take them seriously".[43] Fleming introduced what was a new development for him, a female opponent for Bond, although much like the former adversaries in the series, Rosa Klebb is described as being physically repulsive, with poor hygiene and gross tastes.[44][45] Eco—and Anthony Synnott, in his examination of aesthetics in the Bond novels—consider that despite Klebb being female, the character is more akin to a "sexually neuter" individual.[40] Red Grant was Fleming's first "psychotic opponent" for Bond, according to Benson.[44] Charlie Higson—who later wrote the Young Bond series—finds Grant to be "a very modern villain: the relentless, remorseless psycho with the cold dead eyes of a 'drowned man'."[46]

Style

According to Higson, Fleming spent the first four novels changing the style of his books, and his approach to his characters, but in From Russia, with Love the author "finally hits on the classic Bond formula, and he happily moved into his most creative phase".[47] The literary analyst LeRoy L. Panek observes that the previous novels were, in essence, episodic detective stories, while From Russia, with Love is structured differently, with an "extended opening picture" that describes Grant, the Russians and Romanova before moving onto the main story and then bringing back some of the elements when least expected.[48] The extensive prose that describes the Soviet opponents and the background to the mission takes up the first ten chapters of the book; Bond comes into the story in chapter eleven.[49] Eco called the opening passage introducing Red Grant a "cleverly presented" beginning, similar to the opening of a film.[lower-alpha 3] Eco remarks that "Fleming abounds in such passages of high technical skill".[50]

Benson describes the "Fleming Sweep" as taking the reader from one chapter to another using "hooks" at the end of chapters to heighten tension and pull the reader onto the next.[51] He feels that the "Fleming Sweep steadily propels the plot" of From Russia, with Love and, though it was the longest of Fleming's novels, "the Sweep makes it seem half as long".[49] Kingsley Amis, who later wrote a Bond novel, considers that the story is "full of pace and conviction",[52] while Parker identifies "cracks" in the plot of the novel, but believes that "the action mov[es] fast enough for the reader to skim over them".[53]

Fleming used known brand names and everyday details to produce a sense of realism,[5][54] which Amis calls "the Fleming effect".[55] Amis describes "the imaginative use of information, whereby the pervading fantastic nature of Bond's world ... [is] bolted down to some sort of reality, or at least counter-balanced."[56]

Themes

St. George vs. the dragon

The cultural historians Janet Woollacott and Tony Bennett consider that Fleming's preface note—in which he informs readers that "a great deal of the background to this story is accurate"—indicates that in this novel "cold war tensions are most massively present, saturating the narrative from beginning to end".[57] As in Casino Royale, the concept of the loss of British power and influence during the post-Second World War and Cold War period was also present in the novel.[58] The journalist William Cook observes that, with the British Empire in decline "Bond pandered to Britain's inflated and increasingly insecure self-image, flattering us with the fantasy that Britannia could still punch above her weight."[36] Woollacott and Bennett agree, and maintain that "Bond embodied the imaginary possibility that England might once again be placed at the centre of world affairs during a period when its world power status was visibly and rapidly declining."[57] In From Russia, with Love, this acknowledgement of decline manifested itself in Bond's conversations with Darko Kerim when he admits that in England "we don't show teeth any more—only gums."[58][59]

Woollacott and Bennett argue that in selecting Bond as the target for the Russians, he is "deemed the most consummate embodiment of the myth of England".[60] The literary critic Meir Sternberg sees the theme of Saint George and the Dragon running through several of the Bond stories, including From Russia, with Love. He sees Bond as Saint George—the patron saint of England—in the story, and notes that the opening chapter begins with an examination of a dragonfly as it flies over the supine body of Grant.[61][lower-alpha 4]

The East vs. the West

In the 1950s, there were fears in the West that the Soviet system might prove to be the more efficient system, and it would be the Soviet Union that would win the Cold War.[62] In 1951, two British diplomats, Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess, defected to the Soviet Union, which attracted much publicity at the time.[63] At the time, it was not widely known that Maclean and Burgess were spies for the Soviet Union and in the case of Maclean was on the brink of being arrested on charges of treason. The Soviet government claimed that Maclean and Burgess had defected because life was better in the Soviet Union while the British government was content to go along with this explanation rather than admit that two senior diplomats had been spies for the Soviet Union for the better part of the last twenty years. In September 1955, new information about the Burgess-Maclean affair came out during a debate in the House of Commons when a Labour MP armed with information leaked by the FBI asked questions of the government, which for the first time was forced to confirm that Burgess and Maclean had been Soviet spies, and that in the case of Maclean who had been in charge of the American department of the Foreign Office had provided the Soviets with much highly secret information about Anglo-American relations.[64] The same debate also first raised the question of who was the "Third Man" within British intelligence who tipped off Maclean that he was about to be arrested.[65] The mysterious "Third Man" was eventually revealed in 1963 to be Harold "Kim" Philby, who had once been one of the most senior officers in MI6 who had been slated to become "C", the chief of MI6. Over the decades it was eventually to emerge that Maclean, Burgess and Philby were all part of the "Cambridge Five" spy ring, made up of five men who had been recruited to spy for the Soviet Union while undergraduates at Cambridge University in the early 1930s, and who all went on to enjoy prominent careers in British life.[64] The full extent of the "Cambridge Five" spy ring was not known at the time that Fleming wrote From Russia, with Love, but the question of the mysterious "Third Man" that preoccupied the public provided hints there was a wider Soviet spy ring in the British government, of which Burgess and Maclean were only a part.

The Burgess-Maclean affair, especially the revelations of 1955, painted British intelligence in a very unflattening light, and was used by the American Congress as a reason not to repeal the 1946 McMahon act which drastically restricted the information about nuclear weapons that the United States was willing to provide its allies.[65] The MacMahon act was a major issue in Anglo-American relations at the time, and was the subject of much resentment in Britain.[65] The way in which the Burgess-Maclean affair seemed to confirm the American charge that British spies were no match for Soviet spies, and hence proved the need for the MacMahon act, was one of the aspects of the affair that most hurt British egos.[65] The Burgess-Maclean affair was very much on Fleming's mind at the time he started writing From Russia, with Love.[65] Fleming was greatly offended by the Burgess-Maclean affair, which he often mentioned in his journalism and in his Bond novels in the 1950s, and at least part of his motivation in writing From Russia, with Love was as a sort of rebuttal to the Burgess-Maclean affair.[65] As a former intelligence officer, Fleming was especially upset at the way the Burgess-Maclean affair made British intelligence appear grossly incompetent and easily outwitted by Soviet intelligence.[66]

One of the book's themes is a literacy revenge for the drubbing done to the reputation of MI6 as SMERSH develops a fiendishly complex plot to kill Bond with nothing left to chance, which takes up the first 122 pages of the book, which Bond is nonetheless able to foil and in the process he steals the top secret Soviet code machine.[18] The German scholar Jonas Johan Takors notes that Fleming went out of his way to assert that the novel is based in reality as he stated in his preface that SMERSH is real while also stating that his description of its headquarters in Moscow even down to the descriptions of its conference halls and offices was entirely accurate.[67] Fleming further wrote that "General Grubozaboyschikov" was a real person who as of 1957 was still the chief of SMERSH.[67] In this way, Fleming was asserting that the story he related in From Russia, with Love and its assumptions of Western superiority were all grounded in reality, and were not to be dismissed as mere literacy invention.[67] Takors pointed out that Fleming was not as well informed about Soviet intelligence as he was claimed, noting that SMERSH had been founded in 1943 and disbanded in 1946 while Fleming was also apparently ignorant that the MGB (Ministerstvo gosudarstvennoy bezopasnosti-Ministry of State Security) had been renamed as the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti-Committee of State Security) in late 1953.[67] However, the frequent changes of name for the Soviet secret police, which started out as the Cheka in 1917 were often missed even in the Soviet Union as most Russians including the secret policemen themselves tended to call all secret policemen "Chekists" regardless of what was the official name of the secret police.

In From Russia, with Love Fleming wanted to promote a "West is the best" message by creating two parallel characters who would prove Western superiority over the Soviet Union.[68] Two of the novel's most important characters, Tatiana Romanova and Donald Grant are both defectors who go in opposite directions, and the juxtaposition of the two characters serves to contrast the two systems.[69] Grant is described as a man from Northern Ireland who starts killing animals as a child and moves on to killing people as an adult, being most likely to kill when the moon is in full.[70] Grant is drafted into the British Army in the late 1940s, which temporarily checks his murderous psychopathic tendencies, but he turns against his country when his superiors punish him for his vicious boxing style.[71] The book explains his reasons for defecting as: "He liked all he heard about the Russians, their brutality, their carelessness of human life, and their guile, and he decided to go over to them".[72] Wearing his British Army uniform, Grant deserts his post in West Germany, rides on his motorcycle over to a Red Army post in East Germany and gives his reasons for defecting as: "I am expert in killing people. I do it very well. I like it".[72] Grant, who besides being a soldier who breaks his oath to King and Country by defecting, is portrayed as a madman and as a psychopathic killer.[72] The book's message is that a man like him chooses the East over the West because the Soviet Union is the only place where a perverted, violent man like him can flourish.[72] Grant is portrayed as considerably more happier as SMERSH's number one assassin than he ever was in British service.[72] That Grant shares the same first name as Donald Maclean, the more senior and important of the two diplomats who defected in 1951 may have been intended by Fleming to be a reference to him.[67]

By contrast, Romanova goes from the East to the West. At the beginning of the novel she lives a privileged, if joyless life as an MGB clerk, complaining that the uniform she wears makes it difficult for her to make friends while spending long hours in mind-numbing bureaucratic drudgery.[73] Though portrayed as a committed Communist at the beginning of the novel, she is vaguely unhappy with her life as: "The Romanov blood might well have given her a yearning for men other than the type of modern Russian officer she would meet - stern, cold, mechanical, basically hysterical and because of their Party education infernally dull".[70] Bond both literally and metaphorically seduces Romanova over to the West as he is able to sexually satisfy her in a way that her Russian lovers never could.[70] The way that Bond is portrayed as sexually superior to Russian men was meant by Fleming as a metaphor for how the West was superior to the Soviet Union.[70] Bond also introduces Romanova to the consumerist lifestyle of the West, getting her to wear expensive Western clothing, which she loves and prefers over the cheap Soviet clothing that she had worn until then.[74] Eco considers the Romanova-Bond relationship as another example of "positive human chances" that exist within the Bond books, namely Bond's ability to offer women a positive change in their lives.[70] Bond's relationship with Romanova is portrayed as both a political and sexual liberation for her, letting her enjoy a level of happiness that she never could enjoy in the Soviet Union.[70] The unflattering comparisons between Bond and Romanova's Russian lovers extend even into the manner of personal hygiene as Russian men in the novel are portrayed as having poor personal hygiene and unpleasant body odours, very much unlike Bond.[70] In the end, the decisions made by both defectors serve as a commentary on the respective political systems. The soft and feminine Romanova despite her privileged life in Moscow chooses the West because life there is more comfortable and because true love can only be found there while the hard and masculine Grant chooses the East because it is the only system that a violent madman like himself can excel in.[75]

Throughout the book, life in the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom are constantly compared and always to the advantage of the latter; for example, MGB officers are described as living in fear of their superiors and in one scene General Grubozaboyschikov of the MGB attacks his subordinates with a knout while relations between MI6 officers are portrayed as warm and friendly with M treating Bond with respect and kindness.[69] Likewise, Bond's relationship with his loveable and eccentric housekeeper who will only address Winston Churchill and royalty as "sir" is shown as an affectionate one between near-equals, in marked contrast to the rigidly authoritarian and hierarchical Soviet society.[69] A telling contrast lies in the way that the MGB has a special department store in Moscow set aside for themselves full of goods unavailable to ordinary Soviet citizens while Bond does his shopping at a London department store alongside ordinary British people.[76] In this way, Fleming depicts the ostensibly egalitarian society of the Soviet Union as a sham while Britain is portrayed as the more egalitarian society.[77] Though the MGB is portrayed as a powerful organisation with Grubozaboyschikov boasting that seemingly disparate events such as the Cyprus Emergency, Soviet arm sales to Egypt, strikes in the United Kingdom, Soviet-Yugoslav reconciliation, the Algerian War, revolution in Morocco, and riots in Turkey are all his work, the MGB officers are forced to grudgingly acknowledge that MI5 and even more so MI6 are the better services.[18] Unlike MGB which uses terror to motivate its agents, MI6 is portrayed as the better intelligence service because its agents are motivated by patriotism; education in the public schools and elite universities; and a "love of adventure".[18] Significantly, the MGB characters talk about England instead of Britain, and credit institutions that are seen as more English than British such as the public schools as the reasons for MI6's success.[18] Bond when he arrives in Turkey reflects that MI6's stations abroad are undermanned and its agents underpaid compared to the MGB's stations, but credits their success to the "individualism" of Englishmen which is more than a match for the "mechanical" approach of the Soviets.[69]

Hugh Willard noted that "During the Cold War, the secret agents of the East and West sometimes did kill each other in dark alleys - though probably not as often as they are seen doing in spy thrillers. But blowing up the diplomatic missions of the other side was unheard of, far beyond the pale. For British agents in Turkey to just blow up the Soviet Consulate as an act of private revenge just beggars the imagination. For Bond to just take it in his stride beggars the imagination even more. As soon as Darko Kerim showed Bond the bomb under the Consulate, Bond should have ordered him to dismantle it, there and then. It should have been immediately reported to London. Such a provocative act could have led to Darko Kerim being instantly dismissed as being unreliable and a major security risk, and it might have led to Bond's entire mission being aborted. At a minimum, Kerim should have been severely reprimanded and a regular British intelligence officer stationed permanently in Turkey to keep an eye on him (which should have been done in the first place). (...) Bond inexplicably fails to do anything about it, and eventually Kerim is assassinated on the train and Kerim's vengeful family go ahead and blow up the Consulate - thereby handing the Soviet a major coup on a silver platter. (...) The Soviets had thought up a convoluted plot to destroy Bond and thereby discredit British Intelligence - but British agents blowing up their Consulate would cause British Intelligence a disgrace many orders of magnitude greater. The British could hardly deny it, when digging in the ruins would soon uncover the tunnel leading directly to Kerim's headquarters. (...) Such a scandal would inevitably open a diplomatic rift between Britain and its NATO partner and besmirch the reputation of British Intelligence for years to come. It would not be the agent James Bond who would be at the storm center - his superior M. would be very lucky to survive... "[78]

Other themes

Another theme of the novel is how France is portrayed as the weak link of the West. The French press is portrayed as left-wing and under the control of the Soviet government, which is why Grant is ordered to kill Bond in France in order to ensure maximum publicity for the "death with dishonor" that the MGB is planning to inflict on him.[75] The French Fourth Republic was unstable with governments coming and going while France had been defeated in Vietnam, becoming the first western nation to be defeated by a Communist nation. From late 1954 onward, France was engaged in the bloody Algerian war that was increasingly pushing France to the brink of civil war as the 1950s went on. Grubozaboyschikov alludes to these troubles as he describes France as the nation that the Soviet spies had plunged into chaos and were in the process of steadily taking over, making "great political gains".[18] Some French newspapers had reported (correctly) that the French Army routinely engaged in torture, rape and extrajudicial killings in Algeria, a very controversial claim at the time that divided French society about the justice of the Algerian war. Fleming believed that the FLN was a Soviet-inspired movement and that the criticism of the Algerian war in France was likewise Communist-inspired. That the French press is presented as corrupt and under Soviet control in the book while France is generally portrayed as the weakest link seems to be a reference to these troubles.[75] The lurid murder-sex scandal that is planned is ultimately meant to break up the Anglo-American "special relationship" as Grant taunts Bond that there will be "No more atom secrets from the Yanks".[79] Fleming was indirectly referencing the Maclean-Burgess affair which severely damaged Anglo-American relations and led the United States to cease sharing much intelligence with the United Kingdom for much of the 1950s on the grounds that the British government was a nest of Soviet spies.[79]

An important theme of the novel is heteronormativity. In contrast to the resolutely heterosexual Bond, most of his opponents are not. Rosa Klebb is an ugly woman with "toad like figure" who is a lesbian while Kronsteen is bisexual and "a monster".[70] Klebb tries to seduce Romanova in her apartment, causing her to flee in terror. Reflecting a leitmotif in Fleming's novels when it came to the treatment of villains, the deformed and hideous appearance of the MGB officers serves as a metaphor for their deformed and hideous personalities.[70]

One of major themes of the novel is what Fleming saw as the continuity of Russian/Soviet history with the Soviet Union as merely a continuation of Imperial Russia. At one point, it is objected that Tatiana Romanova who as her surname suggests is related to the House of Romanov, albeit distantly, and thus cannot serve on a mission in Turkey, leading Klebb to say that "all our grandparents were former people. There is nothing one can do about it".[18] Fleming was suggesting that the 1917 revolutions were a sham, and the "former people" (the disparaging Soviet term for the elite of Imperial Russia) in fact continued to rule on after 1917.[18] The fact that Grubozaboyschikov uses lashing with a knout (a favored punishment in Imperial Russia) to punish his subordinates is again meant to show the continuity of Russian/Soviet history. Throughout the book, the term Russia and Russians are used rather than the Soviet Union and Soviets, emphasising the historical continuity.[67] In one passage, it is stated that extreme violence is merely routine state policy in Russia/the Soviet Union, as Fleming wrote in an apparent reference to the Yezhovshchina of 1936-38 that "a million people" had to be killed in one year because it was necessary for the Soviet state.[72] Joseph Stalin is not mentioned as a reason for this violence, and instead the state violence in the Soviet Union is explained on racial grounds as "some of their race are among the cruellest in the world", suggesting the Russians or at least a great many of them are a pathologically warped people.[72] However, the same passage also states the "average Russian" is not a "cruel man". [72] The massive state violence of the Stalin era is not presented as an aberration in Russian/Soviet history, but rather as the norm.[72]

Another theme of the novel is the failure of modernization under the Turkish republic and the picture of the Turks as "oriental".[32] When Bond arrives in Istanbul, he is met by "dark, ugly, neat little officials" with "bright, angry, cruel eyes that had only lately come down from the mountains...They were hard, untrusting, jealous eyes. Bond didn't take to them.".[32] Kerim Bey tells Bond at one point: "That is the only way to treat these damned people. They love to be cursed and kicked. It is all they understand. It is in the blood. All this pretence of democracy is killing them. They want some sultans and wars and rape and fun. Poor brutes, in their striped suits and bowler hats. They are miserable. You’ve only got to look at them. However, to hell with them all. Any news?"[32] That Kerim is half-Turkish and lives in Turkey is intended to give authenticity and authority to passages such as this.[32] When Bond and Romanova board the Orient Express, he thinks: "By tomorrow they would be out of these damn Balkans and down into Italy, then Switzerland, then France — among friendly people and away from these dark, furtive lands that stank of conspiracy and treachery".[32]

Rusya’dan Sevgilerle

Singer noted that in Rusya’dan Sevgilerle, the Turkish version of From Russia, with Love that was published in 1983, the translator Yakut Güneri made major changes to the story that presented Turkey and Turks in a more positive light.[32] All references to the 1955 pogrom in From Russia, with Love are removed from Rusya’dan Sevgilerle.[32] On his flight to Istanbul, Bond stops in Athens where: "Near the airport a dog barked excitedly at an unknown human smell. Bond suddenly realized that he had come into the East where the guard-dog howls all night."[32] The stop-over in Athens is eliminated from the Turkish version.[32] In Istanbul, where Bond is met by "dark, ugly, neat little officials" with "bright, angry, cruel eyes that had only lately come down from the mountains...They were hard, untrusting, jealous eyes. Bond didn't take to them." The reference to Turks being ugly is removed as is the remark about them "had only lately come down from the mountains."[32] The “hard, untrusting, jealous eyes” of the Turks became "hard, fearless, anguished eyes".[32]

Kerim has in his office a portrait of Winston Churchill hanging in a prominent spot together with a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II.[32] Churchill is a hated figure in Turkey who is detested as the First Lord of the Admiralty who confiscated two battleships that the Ottoman empire had paid for in 1914; for his role in launching the Dardanelles campaign of 1915; for advocating British support for Greece and finally supporting David Lloyd George in 1922 when he decided to go to war with Turkey.[32] In Rusya’dan Sevgilerle, Kerim has only a portrait of Elizabeth II.[32] Kerim shakes Bond's hand with "a hand with strength that could break the bones of fingers by squeezing [them]" while the references to the "Western handful of operative fingers" and "the banana skin handshake of the East" are removed.[32] In From Russia, with Love Kerim has two citations for military service for Britain while in Rusya’dan Sevgilerle he has none.[32]

In the English original Kerim tells Bond about his children: "They would all die for me—and for M. I have taught them he is just below God."[32] As this statement might sound rather blasphemous in Muslim Turkey, Kerim in the Turkish version says his children "greatly respect M".[32] The passage about Kerim talks about how the Turks "want some sultans and wars and rape and fun" is removed altogether in the Turkish version where Kerim just asks Bond if he has "any news?"[32] Bond's remark about how Kerim does not "belong outside his territory" is removed from the Turkish version.[32]

Singer concludes: "The cumulative effect of all these changes is that Güneri transforms Kerim from a symbol of a Hail Britannia-enthusiast voicing Fleming's disdain for savage Turks into the epitome of British-Turkish partnership and the sophisticated modern Turk...Turkey is the setting for this adventure, but Güneri and Fleming imagine the country very differently. Turkey and its place in the world thus became points of contention between author and translator. For Fleming, the Darko Kerim character is a critical voice of Kemalism's failed if admirable modernizing mission. In contrast, Güneri allows for Kerim's Britishness and Turkishness (more accurately, a certain type of Turkishness) to comfortably co-exist, which they must if Darko Kerim is to symbolize the possibilities Turkey's modernization has created."[32]

Publication and reception

Publication history

From Russia, with Love was released in the UK as a hardback on 8 April 1957, by the publishers Jonathan Cape.[80] The American edition was published a few weeks later by Macmillan.[19][81] Fleming was pleased with the book and later said:

Personally I think from Russia, with Love was, in many respects, my best book, but the great thing is that each one of the books seems to have been a favourite with one or other section of the public and none has yet been completely damned.[28]

In November 1956 the Prime Minister, Sir Anthony Eden, had visited Fleming's Jamaican Goldeneye estate, to recuperate from a breakdown in his health. This was much reported in the British press,[23] and the publication of From Russia, with Love was accompanied by a promotional campaign that capitalised on Fleming's raised public profile.[82] The serialisation of the story in The Daily Express in 1957 provided a boost to the sales of the book;[83] a bigger rise in sales was to follow four years later. In an article in Life on 17 March 1961, the US President John F. Kennedy listed From Russia, with Love as one of his ten favourite books.[84][lower-alpha 5] This accolade, and its associated publicity, led to a surge in sales that made Fleming the biggest-selling crime writer in the US.[47][86] There was a further boost to sales following the release of the film of the same name in 1963, which saw the sales of the Pan paperback rise from 145,000 in 1962 to 642,000 in 1963 and 600,000 in 1964.[87]

Reception

From Russia, with Love received mainly positive reviews from critics.[88] Julian Symons, in The Times Literary Supplement, considered that it was Fleming's "tautest, most exciting and most brilliant tale", that the author "brings the thriller in line with modern emotional needs", and that Bond "is the intellectual's Mike Hammer: a killer with a keen eye and a soft heart for a woman".[89] The critic for The Times was less persuaded by the story, suggesting that "the general tautness and brutality of the story leave the reader uneasily hovering between fact and fiction".[90] Although the review compared Fleming in unflattering terms to Peter Cheyney, a crime fiction writer of the 1930s and 1940s, it concluded that From Russia, with Love was "exciting enough of its kind".[90]

The Observer's critic, Maurice Richardson, thought that From Russia, with Love was a "stupendous plot to trap ... Bond, our deluxe cad-clubman agent" and wondered "Is this the end of Bond?"[80] The reviewer for the Oxford Mail declared that "Ian Fleming is in a class by himself",[28] while the critic for The Sunday Times argued that "If a psychiatrist and a thoroughly efficient copywriter got together to produce a fictional character who would be the mid-twentieth century subconscious male ambition, the result would inevitably be James Bond."[28]

Writing in The New York Times, Anthony Boucher—described by a Fleming biographer, John Pearson, as "throughout an avid anti-Bond and an anti-Fleming man"[91]—was damning in his review, saying that From Russia, with Love was Fleming's "longest and poorest book".[81] Boucher further wrote that the novel contained "as usual, sex-cum-sadism with a veneer of literacy but without the occasional brilliant setpieces".[81] The critic for the New York Herald Tribune, conversely, wrote that "Mr Fleming is intensely observant, acutely literate and can turn a cliché into a silk purse with astute alchemy".[28] Robert R Kirsch, writing in the Los Angeles Times, also disagreed with Boucher, saying that "the espionage novel has been brought up to date by a superb practitioner of that nearly lost art: Ian Fleming."[92] In Kirsch's opinion, From Russia, with Love "has everything of the traditional plus the most modern refinements in the sinister arts of spying".[92]

Adaptations

From Russia, with Love was serialised in The Daily Express from 1 April 1957;[93] it was the first Bond novel the paper had adapted.[83] In 1960 the novel was also adapted as a daily comic strip in the paper and was syndicated worldwide. The series, which ran from 3 February to 21 May 1960,[94] was written by Henry Gammidge and illustrated by John McLusky.[95] The comic strip was reprinted in 2005 by Titan Books in the Dr. No anthology, which also included Diamonds Are Forever and Casino Royale.[96]

The film From Russia with Love was released in 1963, produced by Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, and directed by Terence Young. It was the second Bond film in the Eon Productions series and starred Sean Connery as Bond.[97] The film version contained some changes to the novel, with the leading villains switching from SMERSH to SPECTRE, a fictional terrorist organisation.[98] In the main it was a faithful adaptation of the novel; the ending was changed to make clear Bond's survival. Benson declares that "many fans consider it the best Bond film, simply because it is close to Fleming's original story".[99]

The novel was dramatised for radio in 2012 by Archie Scottney, directed by Martin Jarvis and produced by Rosalind Ayres; it featured a full cast starring Toby Stephens as James Bond and was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4. It continued the series of Bond radio adaptations featuring Jarvis and Stephens following Dr. No in 2008 and Goldfinger in 2010.[100]

Notes and references

Notes

- Diamonds Are Forever was published in March 1956.[4]

- While in Turkey, Fleming wrote an account of the Istanbul pogroms, "The Great Riot of Istanbul", which was published in The Sunday Times on 11 September 1955.[15]

- The narrative describes Grant as an immobile man, lying by a swimming pool, waiting to be massaged; it has no direct connection to the main storyline.[50]

- Sternberg also points out that in Moonraker, Bond's opponent is named Drax (Drache is German for dragon), while in On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1963) the character Marc-Ange Draco's surname is Latin for dragon, and in From Russia, with Love Darko Kerim's first name is "an anagrammatic variation on the same cover name".[61]

- Kennedy's brother Robert was also an avid reader of the Bond novels, as was Allen Dulles, the Director of Central Intelligence.[85]

References

- Fleming 1957, p. 6.

- Lycett 1996, pp. 268–69.

- "Ian Fleming's James Bond Titles". Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- Lycett 1996, p. 289.

- Faulks & Fleming 2009, p. 320.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 101.

- Benson 1988, p. 13.

- Fleming & Higson 2006, p. v.

- Benson 1988, p. 14.

- Parker 2014, p. 209.

- Lycett 1996, p. 293.

- Lycett 1996, pp. 307–08.

- Chancellor 2005, pp. 96–97.

- Benson 1988, p. 12.

- Fleming, Ian (11 September 1955). "The Great Riot of Istanbul". The Sunday Times. p. 14.

- Griswold 2006, p. 13.

- Chancellor 2005, pp. 98–99.

- Takors 2010, p. 222.

- Benson 1988, p. 16.

- Lycett 1996, p. 300.

- "Bond's unsung heroes: Geoffrey Boothroyd, the real Q". The Daily Telegraph. 21 May 2009. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 160.

- Benson 1988, p. 15.

- Lycett 1996, p. 282.

- Macintyre 2008, p. 90.

- Macintyre 2008, p. 93.

- Halloran 1986, p. 163.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 97.

- Black 2005, p. 30.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 96.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 16.

- Singer, Sean (12 December 2012). "Lost in Translation: James Bond's Istanbul". The American Interest. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Black 2005, p. 28.

- Parker 2014, p. 208.

- Panek 1981, p. 316.

- Cook, William (28 June 2004). "Novel man". New Statesman. p. 40.

- Benson 1988, p. 106.

- Benson 1988, pp. 106–07.

- Benson 1988, pp. 107–08.

- Eco 2009, p. 39.

- Synnott, Anthony (Spring 1990). "The Beauty Mystique: Ethics and Aesthetics in the Bond Genre". International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. 3 (3): 407–26. doi:10.1007/BF01384969. JSTOR 20006960. S2CID 143938867. (subscription required)

- Panek 1981, p. 208.

- Eco 2009, p. 46.

- Benson 1988, p. 108.

- Black 2005, pp. 28–29.

- Fleming & Higson 2006, p. vii.

- Fleming & Higson 2006, p. vi.

- Panek 1981, pp. 212–13.

- Benson 1988, p. 105.

- Eco 2009, p. 51.

- Benson 1988, p. 85.

- Amis 1966, pp. 154–55.

- Parker 2014, p. 198.

- Butler 1973, p. 241.

- Amis 1966, p. 112.

- Amis 1966, pp. 111–12.

- Bennett & Woollacott 1987, p. 28.

- Macintyre 2008, p. 113.

- Fleming & Higson 2006, p. 227.

- Bennett & Woollacott 1987, p. 138.

- Sternberg, Meir (Spring 1983). "Knight Meets Dragon in the James Bond Saga: Realism and Reality-Models". Style. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press. 17 (2): 142–80. JSTOR 42945465. (subscription required)

- Takors 2010, p. 220-222.

- Takors 2010, p. 219.

- Takors 2010, p. 220-221.

- Takors 2010, p. 221.

- Takors 2010, p. 219-220.

- Takors 2010, p. 220.

- Takors 2010, p. 221-222.

- Takors 2010, p. 223.

- Takors 2010, p. 224.

- Takors 2010, p. 224-225.

- Takors 2010, p. 225.

- Takors 2010, p. 223-224.

- Takors 2010, p. 229.

- Takors 2010, p. 226.

- Takors 2010, p. 222-223.

- Takors 2010, p. 22-223.

- Hugh G. Willard, "Real Spies and Thriller Spies", in Dr. Enoch Carter (ed.), "The Mythologies of the Twentieth Century Revisited - a Multi-Disciplinary International Round Table", p. 25, 28, 31.

- Takors 2010, p. 227.

- Richardson, Maurice (14 April 1957). "Crime Ration". The Observer. p. 16.

- Boucher, Anthony (8 September 1957). "Criminals at Large". The New York Times. p. BR15.

- Lycett 1996, p. 313.

- Lindner 2009, p. 16.

- Sidey, Hugh (17 March 1961). "The President's Voracious Reading Habits". Life. 50 (11): 59. ISSN 0024-3019. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- Parker 2014, pp. 260, 262.

- Lycett 1996, p. 383.

- Bennett & Woollacott 2009, pp. 17, 21.

- Parker 2014, p. 239.

- Symons, Julian (12 April 1957). "The End of the Affair". The Times Literary Supplement. p. 230.

- "New Fiction". The Times. 11 April 1957. p. 13.

- Pearson 1967, p. 99.

- Kirsch, Robert R (28 August 1957). "The Book Report". Los Angeles Times. p. B5.

- "From Russia With Love". Daily Express. 1 April 1957. p. 10.

- Fleming, Gammidge & McLusky 1988, p. 6.

- McLusky et al. 2009, p. 5.

- McLusky et al. 2009, p. 135.

- Brooke, Michael. "From Russia with Love (1963)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 21.

- Benson 1988, pp. 172–74.

- "Saturday Drama: From Russia with Love". BBC. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

Sources

- Amis, Kingsley (1966). The James Bond Dossier. London: Pan Books. OCLC 154139618.

- Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcus (2001). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: the Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. London: Batsford Books. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.

- Bennett, Tony; Woollacott, Janet (1987). Bond and Beyond: The Political Career of a Popular Hero. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-416-01361-0.

- Bennett, Tony; Woollacott, Janet (2009). "The Moments of Bond". In Lindner, Christoph (ed.). The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 13–34. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Benson, Raymond (1988). The James Bond Bedside Companion. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85283-233-9.

- Black, Jeremy (2005). The Politics of James Bond: from Fleming's Novel to the Big Screen. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6240-9.

- Butler, William Vivian (1973). The Durable Desperadoes. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-14217-2.

- Chancellor, Henry (2005). James Bond: The Man and His World. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6815-2.

- Eco, Umberto (2009). "The Narrative Structure of Ian Fleming". In Lindner, Christoph (ed.). The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 34–56. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Faulks, Sebastian; Fleming, Ian (2009). Devil May Care. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-103545-1.

- Fleming, Ian (1957). From Russia, with Love. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 368046.

- Fleming, Ian; Gammidge, Henry; McLusky, John (1988). Octopussy. London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-85286-040-0.

- Fleming, Ian; Higson, Charlie (2006). From Russia, with Love. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-102829-3.

- Griswold, John (2006). Ian Fleming's James Bond: Annotations and Chronologies for Ian Fleming's Bond Stories. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4259-3100-1.

- Halloran, Bernard F (1986). Essays on Arms Control and National Security. Washington, DC: Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. OCLC 14360080.

- Lindner, Christoph (2009). The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Lycett, Andrew (1996). Ian Fleming. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-1-85799-783-5.

- Macintyre, Ben (2008). For Your Eyes Only. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-9527-4.

- McLusky, John; Gammidge, Henry; Hern, Anthony; Fleming, Ian (2009). The James Bond Omnibus Vol. 1. London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-84856-364-3.

- Panek, LeRoy (1981). The Special Branch: The British Spy Novel, 1890–1980. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green University Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-178-7.

- Parker, Matthew (2014). Goldeneye. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09-195410-9.

- Pearson, John (1967). The Life of Ian Fleming: Creator of James Bond. London: Jonathan Cape. OCLC 463251270.

- Takors, Jones (2010). "'The Russians could not longer be the heavies' From Russia with Love and the Cold War in the Bond Series". In Korte, Barbara; Pirker, Eva Ulrike; Helff, Sissy (eds.). Facing the East in the West: Images of Eastern Europe in British Literature, Film and Culture. London: Rodopi. pp. 219–232. ISBN 978-9042030497.

External links

Quotations related to From Russia, with Love at Wikiquote

Quotations related to From Russia, with Love at Wikiquote- Ian Fleming.com Official website of Ian Fleming Publications

- From Russia With Love at Faded Page (Canada)